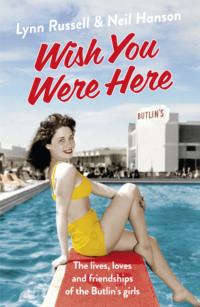

Wish You Were Here!: The Lives, Loves and Friendships of the Butlin's Girls

Dedication

For Hilary, Mavis, Valerie,

Valda, Sue, Terri and Anji

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Hilary

One

Two

Three

Mavis

One

Two

Three

Four

Valerie

One

Two

Three

Valda

One

Two

Three

Four

Sue

One

Two

Three

Terri

One

Two

Three

Four

Anji

One

Two

Three

Epilogue

Butlin’s Rules

Acknowledgements

If you liked Wish You Were Here you’ll love …

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

This is the true-life Hi-de-Hi! story of the Butlin’s girls – the women who worked at Butlin’s holiday camps during the company’s Golden Age, from the opening of the first one at Skegness in 1936 to the 1970s when they were in their prime, before the growth of cheap air travel and overseas package holidays sounded their death knell.

In Wish You Were Here we have drawn on interviews with many of the legendary Butlin’s redcoats, but we have also spoken to waitresses, bar staff, chalet-maids, chefs, kitchen porters, office staff, security men and the many other staff who kept the camps running, as well as to holiday-makers who loved Butlin’s and returned there year after year.

Many redcoats also returned season after season, and some married other redcoats and built their lives around Butlin’s. Others were merely passing through, but even then, they often took away with them experiences and memories that they would draw on and treasure for the remainder of their lives.

The camps began and thrived in an era when – true to their caricature image – seaside landladies really did kick their guests out straight after breakfast and often did not allow them to return until 5 or 6 p.m. Billy Butlin always claimed that the idea for his holiday camps came from the sight of dejected holiday-makers traipsing along the streets of Barry Island under leaden skies while they waited to be allowed back into their ‘digs’. ‘I felt sorry for myself, but I felt sorrier for the families with young children as they trudged around, wet and bedraggled, or forlornly filled in time in amusement arcades until they could return to their boarding houses,’ he claimed in his autobiography, passing over the fact that he probably owned the arcades where these families were spending their holiday money.

Inspiration had struck and Billy began hatching the idea of resorts where holiday-makers could escape the British weather – and be entertained – all day, every day. Even better, his camp staff would also look after the children, no matter how young or old, leaving parents free to please themselves for possibly the only time all year.

Billy Butlin was already rich and successful when he launched his holiday camps. The son of an ill-matched couple, he’d had a restless upbringing. His mother came from a family of travelling showmen, but his father was the wastrel son of a wealthy family, a ‘remittance man’ who went into voluntary exile in South Africa in return for the allowance paid by his long-suffering relations. The marriage soon ended and Billy’s childhood was spent moving between South Africa, England and Canada. His education was sketchy at best, but he was quick-witted and hard-working.

He enlisted in the Canadian Army in the First World War and then worked in a department store before returning to England in 1920, working his passage on a cattle ship. He made his way to his showman uncle’s winter quarters near Bristol and used his last thirty shillings (£1.50 then and about £75 today) to rent a hoopla stall from him at the first fair of the season in a boggy Somerset field. Unlike most showmen at the time, whose prizes were so infrequently won that the metal ones often had to be cleaned to remove the rust, Billy’s were relatively easy to win. That, together with the free advertising of prizes branded with the Butlin’s name being carried around the fairground by the winners, acted as such a successful promotion for his stall that he made ten times the profits of his rivals.

He expanded rapidly, and by the end of the 1920s, he was operating a string of arcades, amusement parks, fairground pitches and zoos all over the country. He was an inveterate gambler, always willing to back his instincts and hunches with serious money, though not all of his gambles succeeded. He lost his pride and joy, a beautiful American limousine, in a card game. He won it back the next night, but then lost it again on a toss of a coin. However, his gamble on holiday camps – he borrowed to the hilt to launch his first at Skegness and nearly went bust before it opened – paid off in style.

The boarding house keepers with whom Billy was competing were often their own worst enemies. Quite apart from driving their guests out from morning till evening, many charged the holiday-makers extra for anything they used. Having a bath was invariably subject to an extra charge and some boarding house keepers even charged for the use of salt and pepper.

Billy Butlin had set his prices at a level he believed working people could afford, coining the eye-catching slogan: ‘A week’s holiday for a week’s pay’. That included accommodation, three full meals a day and free entertainment, for an all-in price of from £1. 15s to £3 a week, depending on the time of year, the equivalent of £90–£150 today. The slogan was slightly misleading, since the price was per head, so for a family of four, the breadwinner would have needed almost a month’s wages to pay for a week at Butlin’s.

The very first Butlin’s holiday camp, at Skegness, opened in 1936. Billy already had a large amusement park in the town and knew the area well. He chose it partly because of its good transport links and closeness to several major urban centres, though the cheapness of the land and the small local population – meaning fewer people to object to his plans – must also have been influential factors.

After scouting the coastline around the town for weeks, Billy Butlin found what he was seeking: a 200-acre turnip field at Ingoldmells, a couple of miles outside of Skegness. Having bought the field, he set to work. He designed the camp himself, sketching plans and jotting ideas on the back of cigarette packets. His background as a showman was evident in his chosen designs – like a fairground, the camp was to be awash with bright lights, vivid colours, music and noise, but there was to be a kind of glamour, too. The main buildings were arranged deliberately to evoke the great ocean liners of the era, regarded as the height of sophistication. Painted brilliant white with coloured detailing, the buildings formed a line with a tower in the middle, echoing the bridge and funnel of a liner.

Billy’s original aim had been to create a camp for 1,000 people with 600 chalets, but it proved so successful that before the first season was out, the capacity had to be more than doubled and it eventually accommodated close to 10,000 holiday-makers. Some of the chalets even had bathrooms, but the majority of holiday-makers had to use communal bath houses and toilet blocks (though even those were a step up from the slum housing in which many still lived).

Campers were made to feel welcome from the moment they arrived. As the buses bringing visitors from the station pulled up inside the camp, a tannoy announced, ‘You have now arrived at Butlin’s holiday camp. We hope you had a pleasant journey and that you will all be very happy here.’

To help them achieve that happiness, Butlin’s Skegness was lavishly equipped with a theatre, a Viennese dance hall, a beer garden, a fortune teller’s parlour and Ye Olde Pigge and Whistle – a half-timbered mock-up of an Elizabethan inn. The landscaped grounds contained rose gardens, a swimming pool with cascades and a fountain, a boating lake and all sorts of sports facilities.

Billy was also one of the first to recognise the commercial possibilities of the emerging celebrity culture. He hired the aviator Amy Johnson – a national heroine after making the first ever solo flight from England to Australia – to attend the opening ceremony of the Skegness camp, and when the cricketer Len Hutton scored a record 364 against Australia in 1938, Billy paid him £100 to appear on stage with a bat made from sticks of Skegness rock while Gracie Fields bowled to him. The champion boxer Len Harvey was also paid to spar with a boxing kangaroo.

However, when the camp first opened, it seemed as if Billy’s grand plan was going to be a failure. People in that era were often quite shy and reserved, and ‘showing off’ or ‘making a spectacle of yourself’ were frowned upon. Almost everybody wore their best clothes when they went to the seaside, and most people didn’t go swimming in the sea at all, though paddling in the shallows with their trousers rolled up or their skirts lifted a decorous few inches was quite acceptable. As one female holiday-maker recalled, ‘Everybody used to point and stare when people came onto the beach in a swimsuit. It was terribly daring to have a swimsuit on at all!’

As Billy walked around the camp, he noticed that very few of those first campers were using the facilities or taking part in the activities. Most of them were keeping themselves to themselves and many looked bored. Desperate for a way to liven them up, Billy asked Norman Bradford to take on the task of cheering up the campers. A gregarious, outgoing character with a good sense of humour, Norman took to his task with gusto, chivvying the holiday-makers into joining in with the activities, putting on a free drink or two to loosen everyone up and keeping them entertained with a string of corny jokes. Norman also claimed to be the originator of the ‘Hi-de-hi!’ catchphrase, to which his audience would respond ‘Ho-de-ho!’

Within a very short time of these innovations, the camp was beginning to buzz. With his characteristic willingness to back his hunches, Billy decided that if British holiday-makers couldn’t enjoy themselves without outside help, then he would employ an army of helpers to make sure they did. They needed a uniform to make them instantly identifiable, so Billy bought a job lot of red blazers; the Butlin’s redcoat had been born.

Despite the hoary old joke that was soon circulating among Butlin’s campers – ‘I’m going to join the escape committee’ – most people seemed to like being told how to enjoy themselves. Many of them had more than enough things to worry about during the rest of the year and actually relished letting someone else take the strain of organising their holiday activities for them. And if they didn’t want to do something, they could always say no, although they needed to be strong-willed, because the redcoats could be very persistent.

Billy was quick to spot problems or opportunities and even quicker to take advantage of them. ‘Can’t’ was not a word to be found in his vocabulary, as the Butlin’s archivist and former redcoat Roger Billington discovered when Billy decreed that water-skiing should be made available to campers at Minehead, and put Roger in charge of organising it.

‘But we’ve never water-skied before,’ Roger said. ‘We’ve never even taken the speedboat out.’

Billy gave him a withering look. ‘There’s a library in Minehead, isn’t there? Well, get a book on it.’

None of the activities we now identify with Butlin’s was invented by its founder. All of them – mass catering, resident entertainers, chalet patrols, semi-compulsory jollity and participation enforced by perpetually smiling staff with a ready stream of catchphrases – were features of the smaller holiday camps that had existed since the later years of the previous century, and of those camps owned by Billy’s business rival, Harry Warner. Still, Billy made them seem new by practising them on a scale never seen before and promoting them with all his showman’s chutzpah and razzle-dazzle.

His formula fitted a ready-made gap in the market, but he also benefited from a piece of very fortunate timing. Until 1938, only two million Britons were able to afford to take an annual holiday and most of them were middle- or upper-class people for whom Butlin’s all-in, all-mates-together style of entertainment was likely to be anathema. However, in that year, the Government passed a bill compelling employers to provide all full-time employees with one week’s paid holiday a year. At a stroke, the number of Britons able to afford a holiday trebled to six million, and many of them, mostly skilled and unskilled working people, began finding their way to Butlin’s.

Not even the outbreak of war in 1939 – just three years after he had opened that first camp, when his second at Clacton was only a year old and the third, Filey, not even completed – could ruin Billy or derail his ambitions. When war was declared, the camps were acquired by the Government as military bases. The Army took over Clacton, the Royal Air Force got Filey and Skegness was taken over by the Navy and rechristened HMS Royal Arthur.

Billy also had to make a wartime alteration of his own. In the late 1930s, the targets on the shooting range at his Bognor amusement park were effigies of Nazi leaders: Hitler, Goebbels, Goering and von Ribbentrop. After the retreat from Dunkirk in 1940, however, with a German invasion now expected at any moment, Billy Butlin hastily arranged for the targets to be removed, lest invading Nazis should catch sight of them and decide to use Butlin himself a target.

At the instigation of his friend General Bernard ‘Monty’ Montgomery, Billy was also hired to provide entertainment centres for soldiers on leave and to construct new military camps at Ayr in Scotland and Pwllheli in North Wales. Like his existing camps, he negotiated a deal for each one, which allowed him to buy them back at the end of the war at a knockdown price. With a hasty refit and a lick of paint, Butlin’s was ready to accept holiday-makers again almost as soon as the last shot was fired.

Billy Butlin’s camps proved hugely popular and hundreds of thousands of people flocked to them every year. Although changing times eventually saw them go out of fashion, causing many of the camps to close in the 1980s, the remaining ones have been reinvented and remodelled for twenty-first-century tastes. Three camps – at Bognor, Minehead and Skegness – survive and thrive to this day, and the name Butlin’s still evokes a smile of recognition in almost everyone, whether or not they ever went on holiday there themselves.

Wish you were here? Many still do.

One

Hilary Cahill was in her late teens when she first heard of Butlin’s in 1957. Born in 1940, she grew up in Bradford in a solid working-class home. Her mum worked in Whitehead’s mill in the city and her dad was a foreman at Croft’s engineering works, so although they were never wealthy and lived in a back-to-back terraced house, with two good wages coming in there was always food on the table.

Her mum was a dark-haired, attractive and lively character. She absolutely loved to dance. It’s where Hilary got her own love of dancing from, because her mum taught her when she was small. However, her dad couldn’t dance to save his life. ‘He used to claim that it was because he’d never had any shoes when he was young,’ she says, ‘and only had boots, but that sounded like a bit of a lame excuse to me. He was still using the same excuse when I was a teenager! My mother and I tried to teach him over and over again, but whatever we tried, it just didn’t work. He had two left feet and that was the end of it! All the mills used to have these big dances once a year and we used to go to all of them, dressed in our best clothes. The real top bands used to play at them, so they were great. My dad used to hate it, though, when we all went to the works’ dances and my mum would be dancing away with people while he was just sitting there, looking on.’

Her dad was so strict that Hilary was still forced to wear little white ankle socks even when she’d left school, but she had a strong independent streak, so she used to go out on Tuesday nights wearing the ankle socks, telling her dad that she was going to the Guild of St Agnes at church, like a good Catholic girl, but then sneak off to the dance hall instead. She’d take off her ankle socks and put them in her bag, put on a bit of lipstick and then dance away with her friends until it was time to go home. However, her dad obviously suspected that she wasn’t quite as good a Catholic girl as she was pretending, because one night he followed her. As she was walking along she felt a hand on her shoulder, and there was her dad looking absolutely furious. ‘I want you back in the house, now,’ he said. ‘Get those socks back on your feet and wipe that dirt off your mouth.’ She was more embarrassed than frightened, but she knew that there was no use in arguing and that it was the end of her Tuesday-night excursions to the dance hall.

Her brother was five years older than her and almost as strict as her dad. He used to go to the same dance hall as Hilary and her friends and, she says, ‘He always kept his beady eye on me!’ She didn’t mind that – she quite liked the idea of her big brother being around. They were good pals, despite the age difference between them – and five years was a lot at that age. He didn’t snitch on her to her dad, but he would certainly let her know if he thought she wasn’t behaving like his little sister was supposed to. After her brother left school, he worked as a wool sorter and then did his National Service. She didn’t see him for almost two years because he was serving out in Cyprus during the troubles there, and she missed him a great deal.

Hilary went to a Catholic school in Bradford, but, looking back, she couldn’t say it was a very good education, and like the majority of her school year, she left at fifteen with no qualifications. Her first job was at J. L. Tankard’s carpet and rug factory in Bradford. She was employed in the finishing department, doing hand-sewing. It was all piecework and hard graft, but as young girls do, she and her workmates had a few laughs along the way.

One of her friends, Brenda, was a dab hand at doing hair and used to style theirs for them in the toilets at work. The girls would give her some of their ‘tickets’ – the slips of paper detailing the piecework jobs they’d done – so that she didn’t lose out financially from the time she was taking off work to cut their hair. ‘The Grecian styles were in then,’ Hilary says, ‘so we were all there at work with steel wavers and pin curls in our hair, singing along to the songs on the radio.’ After work they all used to go dancing together. Once she was paying her own way in the household, Hilary’s dad had to ease the restrictions on her, and from then on she and her mates were out every night of the week, either in the Sutton Dance Hall, the Somerset, the Queen’s or the Gaiety. ‘We used to go all over to dance,’ Hilary says.

Hilary and her workmates used to pay into a kitty to save for all sorts of things, including what they called the ‘Christmas Fuddle’. It took only a penny or twopence a week each, but when Christmas came around, that was enough to buy plenty of drinks, crisps and sausage rolls, and on the last day before the Christmas holidays they would stop work at lunchtime and wolf down the lot! Very few of them drank as a rule, but they certainly made up for that at the Christmas Fuddle. Deaf to parental warnings to ‘never mix your drinks’, they drank bottle after bottle of Babycham, Cherry B, Pony and Snowball – so much so that Hilary was pretty ill one year, and when she got home her parents weren’t impressed by the state she was in. The next morning, suffering her first hangover, Hilary wasn’t very impressed either.

As well as the kitty for the Fuddle, Hilary and the other girls were also saving for a holiday together, having made up their minds to go to Butlin’s at Skegness the following summer. They saved up all year, putting away whatever they could afford. Hilary used to put five shillings a week (25p) into a little tin towards her holiday, and saved half a crown (12½p) for clothes and shoes. She had to give her mum money for her board as well, and whatever was left after that she’d usually spend on going dancing.

There were fixed holiday times in all the industrial towns and cities then, when factories and mills would shut down for their annual clean-up and overhaul; an avalanche of, say, West Midlands car workers would descend on the holiday resorts one week, followed by Lancashire mill workers the next and Yorkshire miners the week after. In Lancashire mill towns the annual holidays were called ‘Wakes Weeks’, in other areas they were called ‘Feasts’ and in Bradford the holiday was known as ‘Bowling Tide’ – which was nothing to do with bowls, since Bowling was one of the Bradford districts and ‘tide’ was the local word for a holiday, as in Whitsuntide.

One woman from Bradford remembers her holidays as always being a bit of a home from home, because everyone from her street went on holiday to the same place at the same time. ‘You knew everyone when you got there, because it was all people from your street. I mean, you weren’t with any strangers, because even if you didn’t know them as such, you knew their faces.’ Since all the mills and factories in an area would shut down for the same week, tens of thousands of people were going on holiday at once, and they had to book far in advance – months or even a year ahead – because popular destinations like Butlin’s became full up very quickly.

In the 1940s and 1950s, when Butlin’s was at its peak, there were virtually no package holidays, and only the well-off could afford to travel abroad, so the holiday camps had a vast semi-captive market. The chalets may have been basic, but at a time when many young couples spent their first years of married life under the roof of one of their parents, a chalet at Butlin’s was often their first real taste of domestic privacy.

Very few families owned a car and the fact that everything you could want was in one place at Butlin’s was another powerful attraction. Once they got there, wives were freed from the toil and drudgery of factory work or housework – or both – for a whole week; few families could afford to stay for a fortnight. An article in Holiday Camp Review in 1939, ‘Holiday Camps and Why We Go There’, even claimed the camps were pioneering women’s rights. ‘At a camp alone a woman gains that pleasing sense of equality. The girl of eight, the maiden of eighteen, the grandma of eighty, rank with the boy, youth and grandpa without any sort of distinction. They are campers, first, last and all the time. Age and sex do not matter.’ It’s hard to think of any other British institution at the time where similar claims could be made with a straight face.

Unless they were in a self-catering chalet to save money (and they weren’t introduced until the 1960s anyway), there was no cooking, washing or cleaning for the women to do, and even childcare could be handed over to the nursery nurses or the redcoats in their signature red jackets, white shirts and bow ties, white trousers and white shoes. The children were marched off to sports tournaments, swimming galas and the Beaver Club (for small children) or the 913 Club (for nine- to thirteen-year-olds), or, if the weather was wet, to the endless array of rides, games, sports and competitions held in the ballroom and children’s theatre. So while their kids ran wild in safety, parents could swim or play sports if they felt energetic, or put their feet up and relax if they didn’t. They could sunbathe if the weather was fine, doze in an armchair if it wasn’t. They could play bingo or even booze the day away in the bar if they felt like it.