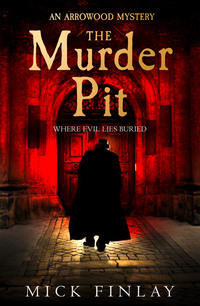

The Murder Pit

‘They’re an important family, sir,’ I said. ‘Isn’t the Duke a Knight of the Garter?’

He snorted. ‘Holmes used to be more discreet.’

‘You don’t know it was Holmes told the press.’

‘You’re right. It was no doubt Watson, trying to sell a few more books.’

There were no cabs at Catford Bridge station so we walked down past a row of almshouses towards the green. It was a frosty day, the sky low and dark over the buildings. Though it wasn’t bright, it was some relief to be out of the murky air of the city. I felt my steps grow lighter, my head clear.

Catford was an old farming village being eaten by London. There was building work going on everywhere: a tramway to Greenwich was being laid; bricklayers were putting up the walls of a bank next to the pump; foundations were being dug out for a grand new pub. Off the main street, past the small houses near the station, big villas for merchants and city workers were rising. Poorer areas were hidden here and there, in the shadows of the tram depot and the forge, where the families of farm workers lived in rickety sheds and damp basements, crammed into wretched houses with boarded windows and broken gutters.

The Plough and Harrow was just the sort of place you found outside town – a stone floor that could have done with a broom for the mud, walls panelled in dark wood, a half door that served as a counter. A glum grandma sat with a blank-faced younger fellow on the benches at one side of the fire, while three old blokes with veined cheeks and pipes in their mouths played dominoes on the other. An ancient dog with matted hair chewed a stick by their feet.

‘Any cabs around here, madam?’ the guvnor asked the landlady after we’d got a couple of pints.

‘The lad may take you in the cart if it’s local,’ she answered. She wore a cowboy hat like you see in the Buffalo Bill shows.

‘The Ockwell farm,’ said the guvnor. ‘D’you know the family, madam?’

‘Godwin’s in here often enough. Why you asking?’

‘We’ve some business with them, that’s all,’ answered the guvnor, taking a swig of his porter. He smiled at the lady. ‘I do like that hat.’

‘Why thank you, pardner.’ Her face softened; she ran her finger along the edge of the brim. ‘American fellow gave it me.’

‘Decent people, the Ockwells,’ growled one of the old men by the fire. ‘Family been here two hundred year at least, maybe more.’

‘They be straight with you long as you be straight with them,’ said another. He lifted his foot and shoved the old dog away from their table. ‘Ain’t nobody’s fools, if that’s what you’re thinking.’

The door opened and two builders, both with wild, grizzled beards, walked in. One was a big, bald fellow wearing a muddy moleskin suit with two jackets, a peaked cap topped with a knob of wool. The other was just as tall but thin, a red cloth wound around his neck, his corduroy jacket covered in rips and poorly made repairs. A shock of hair sprouted from his cap and ran into the tangle of his beard.

‘Morning, Skulky, morning, Edgar,’ said the landlady, setting out two tankards for them. Without a word, they began to drink.

‘The brothers are up Ockwell farm at the minute, fixing their well,’ she said to us. ‘Ain’t you, lads?’

‘That’s their concern, is it?’ asked the thin bloke.

‘These gentlemen was just asking about the farm, Skulky,’ she said. ‘Got some business with them.’

‘From London, are they?’ he asked.

‘South London,’ I said. ‘You know the family, do you?’

‘Perhaps you could tell him this ain’t London, Bell,’ said the bald one, scratching his beard. ‘Perhaps you could tell them folk respect each other’s privacy down here.’

The builders finished their pints and left.

Chapter Three

Five minutes later, a boy of nine or ten came in and led us out to an ancient cart. He drove us down along the green, turning off the main road onto a narrow dirt lane where the houses gave way to fields. We lurched and rocked down a hill then began to climb again. At the top we joined another lane more pitted and uneven than the last. On either side were fields of frozen mud and frosted grass. Little huts were scattered here and there, and pigs stood around everywhere like fools. A cold wind raced across the land.

‘Up there, sir,’ said the boy.

Ahead we could see the farm buildings. Two barns, a stables, some tumbledown animal sheds with rusty corrugated iron, and on the other side of them a big house. Everything looked like it needed fixing: slates were missing from the roofs, doors sat crooked, weeds grew from the guttering. A couple of old ploughs lay broken and mouldering outside the gate. Nothing about that farm looked right. And just as I took it all in, the dogs began to bark.

They guarded the main gate, straining at their ropes in a wild fury. One was a white bull terrier, all muscle and teeth, the other the biggest bull mastiff I ever saw. Its short coat was tan, its snout black. Instead of trying to get past them, the boy drove the cart around the back of a barn and in a side entrance right next to the house. When the dogs saw us appear again, they hurtled back across the yard but were brought up just short of the wagon by their ropes. It didn’t improve their temper none.

‘Mr Godwin fights them,’ said the boy. ‘Best in Surrey, they reckon.’

Just then, a couple of filthy men came through the main gate and crossed to one of the huts on the other side of the yard. Both wore coarse old clothes, smocks bulked out with what looked like sacks padded underneath them. One stared at us, his muddy face thin and severe. The other, a Mongol, waved with a great, wide smile. I waved back. He wore just the crown of a bowler hat upon his head, the rim missing. The mastiff sniffed the air, turned away from us, and tore off towards the workers. The Mongolian let out a cry, a look of horror on his face, while the thin bloke grabbed his sleeve, pulling him into the shed before the dog reached them.

We climbed down from the cart, the guvnor keeping his eye on the bull terrier, who snarled and strained at its rope just ten foot from us. The yard, which would have been nothing but thick mud on a warmer day, was frozen solid, rutted and pitted and hard to walk on. A pile of dung the size of a brougham lay up against one of the stock sheds. The farmhouse itself had seven windows upstairs, six below, with a green-tiled dairy at the far end. Everything was gone to seed: the walls of the house were spattered with mud up to the eaves; the chimneys were cracked and in need of repointing; the thatch was rotted, bare in places, ragged.

The guvnor knocked hard on the door. Nobody answered, but after we’d knocked a few more times one of the sheds wrenched open and a man stepped out. He wore a patched canvas apron that went down to his boots. Mixed with the mud that covered it were bloody smears of purple and crimson, stuck with bits of yellow fat. Behind him in the shed, a row of white pigs hung upside down from a beam, twitching and bewildered, the odd, defeated grunt falling from their lips.

The man’s face was wet with sweat. His blond hair was thinning and combed tight over his forehead, across which was a red line where his cap would have sat. His eyebrows and eyelashes were also blond, giving him a half-born look. He walked toward us, stopping to pet the dogs on his way. They went quiet at his touch.

‘Morning,’ he said when he reached us. He looked at us in a strange, innocent way.

‘We’ve come on official business to see Birdie Ockwell, sir,’ said the guvnor, his eyes fixed on the butcher’s apron. ‘Are you her husband?’

The man stepped in the house and shut the door.

The guvnor was about to knock again when I stopped him.

‘Wait a bit, sir.’

He pressed his ear to the door and listened. After a few minutes, it opened again. She was a small, pinched woman, her eyes keen and bright, her mouth down-turned. A silver cross hung from her neck.

‘Yes?’ she asked, taking us in with a quick flick of her eyes.

‘I’m Mr Arrowood,’ replied the guvnor. ‘This is my assistant, Mr Barnett. We’re here to see Birdie Ockwell.’

‘I’m her sister-in-law,’ said the woman sharply, her accent not as poor as her clothes. ‘I look after Birdie. You may talk to me about anything that concerns her. What matter is it?’

‘It’s a legal matter concerning her family, Miss Ockwell,’ answered the guvnor, lifting his document case for her to notice. ‘Something I believe she’ll be pleased to hear.’

She looked at the case for a moment, then showed us through to the parlour. It was five times bigger than the Barclays’, the furniture grand and solid, expensive in its time but now aged. The long sofa and chairs were frayed and split at the padding, the oak chest scratched and chipped. The big Persian rug was faded, eaten bare in places by moths. By the window stood the newly born man, his fingers fiddling with his bloody apron.

‘Lawyers, Walter,’ she announced. ‘Bringing some good news for Birdie.’ She turned to us. ‘This is her husband, Mr Arrowood. You can tell him, I suppose?’

She crossed the room, sat in a low chair under a lamp, and began to sew.

‘What’s it about?’ asked Walter. He had the same accent as his sister, but his voice was slow and over-loud. ‘Someone left her some money, did they?’

‘We really must speak directly to your wife, Mr Ockwell,’ said the guvnor. His tone had changed. At the door he was gentle and friendly, but now, in the house, his voice was hard as a judge handing out sentence. ‘Please summon her immediately.’

‘She’s not here,’ said Walter.

‘I’d appreciate it if you’d be more specific,’ said the guvnor. ‘I do have other things to do today. Where exactly is she?’

‘Visiting her parents, isn’t she, Rosanna?’ said Walter, looking back at his sister.

‘Oh, dear, dear.’ The guvnor tutted and shook his head. ‘We’ve come such a long way. We’ll have to go directly to the Barclays’ house, I suppose.’ He picked up his briefcase and turned to me. ‘Come, Mr Barnett. Saville Place, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘My, but this has been a waste of time.’

He marched towards the door with me behind him.

‘Wait, Mr Arrowood,’ said Miss Ockwell, getting up from her chair. She smiled, straightening her skirt. ‘It isn’t her parents she’s visiting but Polly’s. Our brother Godwin’s wife. Walter has a habit of only half-listening. Due to spending so much time with the pigs, so we like to tease him. The old woman’s poorly so it wouldn’t be right for you to visit Birdie there, but if you just tell us what it’s about we’ll make sure she knows.’

‘Please, Miss Ockwell. I’m a busy man and I’ve little patience for repeating myself. When will she be back?’

‘Tomorrow.’

‘Then she must come to London to see me. Send me a note with a time, either tomorrow or the day after. No later. We need to conclude the affair.’

‘Of course, sir,’ said Miss Ockwell.

The guvnor gave her the address of Willows’ coffeehouse on Blackfriars Road, the place where we usually arranged our meetings.

She walked us to the hallway.

‘We’ll tell her when she returns,’ she said as she opened the door. ‘It’s about a will, did you say?’

‘As soon as possible, Miss Ockwell,’ replied the guvnor, jamming his hat on his head. ‘Good day.’

Outside, the lad was shivering. The dogs were over the other side of the yard with Edgar, one of the builders who’d welcomed us in the pub. He was feeding them something out of an old rag, stroking them as they ate. He stood up when he saw us and muttered to his brother, who was hammering at something inside the wide doors of one of the stock sheds. Skulky stopped, his red cloth tied tight over his mouth, the mallet clenched in his hand. The two of them watched us as the lad drove out the side of the yard.

We rolled along behind the long barn, then onto the rutted drive and past the main gate. When we were out of sight of the builders, the guvnor asked the lad to stop. He turned to look back at the ragged farmhouse, his face hard, his eyes screwed up against the wind. He shook his head. Alone on the top of the hill, under the heavy grey sky, that wretched farm looked like the sort of place you could arrive at and never leave.

‘Look,’ he murmured.

One of the leaded upper windows was opening. We couldn’t make out anything behind the thick, black glass, but a hand appeared, throwing something light into the breeze. The window closed. It was a long way off, but we could tell what it was by the way it rose and danced in the air, drifting and twisting before disappearing behind the barn.

It was a feather.

The guvnor turned to me and nodded.

‘She’s in there,’ he said.

Chapter Four

When we went for coffee the next afternoon, Ma Willows handed us a wire. It was from Rosanna Ockwell, saying that Birdie was back and that they’d call on us the next day at four. The guvnor clapped me on the back, collected the newspapers from the counter, and sat heavily on a bench by the window.

‘Some of that seed cake, Barnett!’ he called over, flicking through the Pall Mall Gazette. ‘Big slice, Rena, if you don’t mind,’ he added.

Rena Willows rolled her eyes at me. Her coffee shop wasn’t the finest place, but we’d done a lot of our business there over the years and Rena never interfered. I wondered sometimes if she had a fancy for the guvnor, unlikely as that seemed with his head like a huge turnip and that belly as stretched like a great pudding right down between his legs when he sat.

He ate the cake down quick, as if he hadn’t eaten for days though I knew from my own eyes that he’d wolfed a great plate of oysters not two hours before. He blew on his mug of coffee and wiped the crumbs from the newspaper.

‘D’you reckon they’ll bring Birdie?’ I asked him.

‘They’re living on their uppers by the look of that farm. If they think there’s an inheritance, they’ll bring her.’

‘Why did you act so short with them yesterday?’

‘They didn’t strike me as people who’d be affected by kindness, Barnett. People like that are impressed by authority. When they decided I was a lawyer, it seemed a good idea to try and confirm their expectations, and better to do that by my manner rather than by telling them falsities. Birdie was in that house, I knew it as soon as Walter told us she was at her parents. It couldn’t have been a mistake: she hasn’t seen her parents since the wedding and he’d certainly know that. The man just doesn’t think quickly enough to lie well.’ He gurgled as he sipped his coffee, then without warning sneezed over my hand. ‘But why won’t they let us talk to her? That’s the question.’

‘Maybe Walter’s hurt her and they don’t want anyone to see it,’ I said, wiping myself off on my britches.

‘Well, with luck we’ll have a look at her tomorrow. We must get the Barclays here at the same time; we may just close the case. Not even Holmes could have done it faster. I had a note from Crapes this morning by the way: he might have some work for us. Just as well, as we’ll not be earning much from this one.’

Crapes was a lawyer who sometimes put work our way. It usually meant keeping a watch on a husband or wife for a few days and trying to catch them in an affair. We didn’t much like those cases: what the guvnor really wanted was something as would earn him a reputation, as would get his name in the papers like that other great detective in the city.

He turned back to the paper spread out on the table before us.

‘Did you hear about this lunacy case in Clapham?’ he asked after a while. ‘The woman didn’t believe in marriage. She wanted to live with her lover, so the family had her committed to the Priory. They found a doctor to diagnose her with monomania.’ He looked up at me. ‘Caused by – listen, Barnett, I’m talking to you – caused by attending political meetings while menstruating. Have you ever heard of such a thing?’

I shook my head.

‘No, because the fool doctor’s just made the diagnosis up,’ he said, turning the page violently. Immediately his brow dropped and a groan came from his throat. I looked down to see what irked him:

LORD SALTIRE FOUND SAFE. SHERLOCK HOLMES SOLVES MYSTERY. ‘BEST DETECTIVE THE WORLD HAS EVER KNOWN,’ SAYS DUKE OF HOLDERNESSE.

The whole column was given to the story. The guvnor breathed heavy as he read it, shaking his head in despair.

‘What’s he done now?’ I asked.

‘Earned himself six thousand pounds, Barnett,’ he said, flinging the paper across the coffee shop. His lip quivered like he was weeping inside. His voice dropped to a whisper.

‘For two days’ work.’

We were back at Willows’ the next afternoon. It was already getting dark, and a cold rain had been falling all day. The Barclays were inside, wrapped in their coats and hats like they were sat on an omnibus. Mr Barclay was nervy, his pink face pinker from being out in the freezing wind, while Mrs Barclay sat calm and noble, her chin high, looking over the other punters. The guvnor, afraid that Birdie might do a runner when she saw her parents, moved them to a little table at the back of the shop, behind a bunch of cabbies having a break from the cruel streets.

‘This is your chance to see how she is,’ he said. ‘Be gentle and don’t do anything that might anger Walter. Don’t accuse him. And don’t make your daughter feel guilty.’

‘Of course not,’ said Mr Barclay. His eyes darted here and there; his leg jiggled, making the table shudder.

‘Barnett, go and wait outside. Let them enter first. If they turn back when they see Mr and Mrs Barclay you must block the door until I’ve a chance to persuade them.’ He turned back to our employers. ‘Then it’ll be up to you.’

I went and stood on the street, my hands jammed in my pockets against the cold, my cap collecting the fine rain. Three empty hansoms were parked by the kerb, their melancholy horses standing silently. Two young girls out on the monkey wandered past, their hands out to everyone they passed. On the other side, a crumpet man marched along with a tray on his head, clanging his bell and wailing, but he surely knew that nobody eats crumpets in the rain.

It wasn’t long before I saw Rosanna Ockwell striding down Blackfriars Road towards me. She was wrapped in a thick brown coat, a scarf, a plain black bonnet tied under her chin.

‘Mr Barnett,’ she said with a brisk nod. ‘He’s inside, is he?’

‘He is.’ I opened the door for her.

She stepped into the shop, looking around the busy tables until her eyes fell on the Barclays.

‘What’s this?’ she asked sharply, turning back to me. ‘Why are they here?’

‘It concerns them, ma’am,’ I answered, blocking the door.

She glared at me, anger in her keen eyes. There was something uncanny about those eyes: when she laid them on you it was as if she could see your every weakness, every bad thing you’d done.

‘Is Birdie with you, Miss Ockwell?’ asked the guvnor, rising from his seat.

‘Around the corner,’ she replied, turning to him. Her face was quite white except the few strong hairs about her lip. ‘She won’t come now, though. Not with these two here.’

‘But why not?’

‘She doesn’t want anything to do with them, that’s why. They never treated her right. Never wanted her.’

‘It’s a lie!’ cried Mr Barclay, leaping from the table. ‘It’s your family that’s put her up to it! You fetch her here, or there’ll be trouble, I warn you!’

The cabbies had gone quiet, turning on their benches to watch the show. Rena stopped her work and crossed her arms over her great belly.

‘Pray, have a seat, Miss Ockwell,’ said the guvnor in his softest voice. ‘Let’s talk this out.’

‘She wants rid of them.’

‘She does not!’ shrieked Mr Barclay, slapping his hand down hard on the table. ‘You’re a damned liar!’

‘Be quiet, Mr Barclay!’ barked the guvnor.

‘Birdie’s a young lady that needs someone to stand for her and I’m happy to do it, Mr Arrowood,’ said Rosanna. She spoke clear and firm. ‘I promised Birdie to keep them away and that’s what I’ll do.’

‘Oh dear, dear,’ said the guvnor. ‘But there’s some negotiation. Details and so on.’

‘I won’t allow them to talk to her. They only upset the poor girl.’

Mr Barclay jumped to his feet again.

‘Who the blazes d’you think you are telling us we can’t speak to our own daughter?’ he cried. ‘It’s you that’s poisoned her to us, madam. You and your blasted brother. Take us to her now or there’ll be trouble!’

‘Sit down, sir!’ said the guvnor. He turned back to Miss Ockwell, took her arm gently, and led her toward the counter so as the Barclays couldn’t hear.

‘Don’t fight with them,’ he said, his voice low. ‘We’ll never get this business done that way, and we do need her, Miss Ockwell. How about you go and get her, eh? I’ll control Mr Barclay.’

As he spoke, Mrs Barclay rose from the table and crossed the room. She pushed past me, opened the door to the street, and stood holding it for Miss Ockwell, her long face with its three teardrop moles sombre beneath her neat hat.

‘What are you doing?’ asked Mr Barclay. ‘We haven’t finished!’

‘We’ll wait for you here, madam,’ said the guvnor to Miss Ockwell.

Miss Ockwell turned to leave, but as she reached the door, Mrs Barclay, quite a foot taller, stepped in her way. For a moment there was confusion as Miss Ockwell tried to get past, first this way, then that. Then, just as suddenly, it was over and she’d left the shop.

‘What the blazes did you do that for, Martha?’ asked her husband.

‘You were making it worse, Dunbar.’

‘Get after her, Barnett,’ said the guvnor. ‘Make sure they come back.’

I was already out the door as he said it. Up ahead I could see the short figure of Rosanna Ockwell, marching quick towards St George’s Circus. I ran after her through the crowds. At the junction she turned down Charlotte Street. I reached the crossroads just in time to see her going into the Pear Tree Tavern, a big place near the corner.

I waited outside for a few minutes in the wet, but it wasn’t a pub I knew and I started to worry there was another way out round the back. Just as I was crossing to go inside, a hansom came out one of the side alleys, pausing to let a coster’s cart loaded with turnips pass on the road. The street there wasn’t too well-lit, and it was only when the cab began to move off that I saw the three figures inside. It was Rosanna and Walter, both staring ahead in silence. A woman sat on the far side of the cabin. Her face was turned to the other window, but I knew it had to be Birdie.

I guessed they must be going to London Bridge station, so I hopped into a passing hansom. When we arrived, I raced up the stairs and saw them ahead making their way to the platform. Walter towered over the two women; though Rosanna could only have been five two or so, Birdie was even shorter.

The train was waiting, its steam up.

‘Oi!’ I shouted, running over to them.

They turned. Birdie’s mouth hung open in her thin face; her old coat and drooping felt hat were made for a thicker woman. In real life she did look like a birdie, like a finch with a tiny, hooked beak and round, innocent eyes.

‘You chased us?’ demanded Miss Ockwell.

‘You said you were coming back, ma’am,’ I said.

‘She didn’t want to, did you, Birdie?’

Birdie looked at me curiously, her eyes deep and brown like her mother. One of her hands was bandaged round and round in a stained rag. In the other she held a grey pigeon feather. She said nothing.

‘I’m Norman, ma’am,’ I said to her. ‘I know your mother and father.’

‘Hello, Norman,’ she said, her voice low. Her mother’s gentle smile appeared on her face.

‘I like that feather,’ I said.

She held it up to show me, her smile lightening up the gloomy station. I smiled back.

‘Your parents really miss you, Birdie,’ I said. ‘They’re only round the corner. Would you like to come see them?’