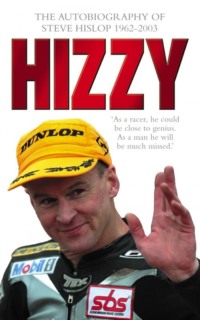

Hizzy: The Autobiography of Steve Hislop

Every day for weeks – even though I don’t believe in God – I prayed for some feeling to come back, but every day for weeks it didn’t. I tried to build up strength in it but could only lift light weights and I was starting to get really depressed thinking my career was over and that I was going to be left with a useless arm. I couldn’t even try to set up a deal for the following season because I didn’t know if I’d be able to ride a bike or not.

Then one day, about two months after the crash, it started happening. I felt a slight sensation on the back of my hand and then in my index finger. It wasn’t much but it was definitely something. I thought, ‘Yes! Here we go, I’m back in business.’ I felt totally elated but not as elated as I was when, near Christmas time, I was finally able to lock my left arm out fully. That was the best Christmas present I’d had since my first son was born on Christmas Day in 1997. I was over the moon.

It was game on after that and I started training slowly and gently to rebuild some muscle in my wasted arm. That was day number one of life number two as far as I was concerned and I never stopped thinking about racing after that. There were still some months until the start of the new season so I had time to try and organize a ride for the year, even though I’d burned my bridges with most teams over the last few years. But I didn’t care – I’d been given a second chance at life and I wasn’t about to waste it. Somehow I would find a bike to race even if it meant remortgaging my house and buying one myself. The way I saw it, I had nothing to lose because I should have been dead anyway.

Steve Hislop was back – and he was going to win the British Superbike championship come hell or high water.

2 Shooting Crows

‘My real name’s actually Robert Hislop but my dad made a mistake when he registered me.’

The Isle of Man TT is a totally unique event and probably attracts more controversy than any other sporting fixture on the calendar.

It’s held on the world famous ‘Mountain’ circuit that runs over 37.74 miles of everyday public roads on the Isle of Man. The roads are, naturally, closed for the races but they’re still lined with hazards such as houses, walls, lamp-posts, hedges and everything else you would expect to find on normal country roads.

Because of the dangers and the number of competitors who have been killed there, the event lost its world championship status in 1976 when top riders like Barry Sheene, Phil Read and Giacomo Agostini refused to race there any longer. When you consider that the current, fastest average lap speed is held by David Jefferies at 127.29mph and bikes have been speed-trapped at 194mph between brick walls, it’s easy to understand the dangers of the place, as there’s no run-off space when things go wrong. But the thrill of riding there is unique and that’s what keeps so many riders coming back year after year.

Riders don’t all start together at the TT – they set off singly at 10-second intervals in a bid to improve safety although mass starts have occurred in the past. That means the competitors are racing against the clock and the longest races last for six laps which equates to 226 miles and about two hours in the saddle at very high speeds and on very bumpy roads. It’s an endurance test as much as anything else and you can’t afford to lose concentration for a split second or you are quite literally taking your own life in your hands. It is an event like no other on earth.

The TT (which stands for Tourist Trophy) fortnight is traditionally held in the last week of May and the first week of June and the Manx Grand Prix is traditionally held on the same course in September. The latter event is purely amateur with no prize money and it exists as a way for riders to learn the daunting 37.74 mile course before tackling the TT proper. The name should not be confused with the world championship Moto Grand Prix series because the two have nothing in common.

Both the Manx Grand Prix and the TT races have played a huge part in my life, which is why I’m describing them in detail now. Without them I simply wouldn’t be where I am today, or even writing this book, and a basic understanding of the nature of both events is crucial to understanding my later career.

I first visited the Manx GP as a child, then later on spent 10 years racing on the Mountain course, both at the Manx and the TT. I grew to love the Isle of Man so much over the years that I moved there in 1991 and it’s where I still live to this day.

It was my father Alexander, or ‘Sandy’ as he was known, who got me interested in the TT and the Manx GP in the first place as he raced at the Manx back in the 1950s. I went on to have incredible success at the TT and that’s really where I made my name in the world of motorcycling. But believe it or not, the Steve Hislop who won 11 TT races (only two men in history have won more) isn’t actually called Steve at all thanks to one of the daftest blunders anyone’s dad ever made.

I may be known as Steve Hislop throughout the bike-racing world but on every piece of documentation that proves who I am, the name given is actually Robert. I still don’t know exactly how it happened but it was definitely my dad’s doing. Both he and my mum, Margaret, had decided on calling me Steven Robert Hislop and that’s the name I was christened under, but my dad messed up big time. For reasons known only to him, he registered me as Robert Steven Hislop and to this day even my passport carries that name.

Robert was my grandfather’s name, but he died when he was just 30 after he fell from the attic in his dad’s blacksmith’s workshop. His was the first in a series of tragic early deaths in my family.

I was born at 7.55pm on 11 January 1962 at the Haig Maternity Hospital in Hawick in the Scottish Borders. But although I was born in a Hawick hospital, I’m not actually from the town itself despite what all those race programmes, TV commentators and magazine articles have said over the years. I’m actually from the little village of Chesters in a parish called Southdean, a few miles south east of Hawick. My mum was only 16 when she had me, while my dad was a good bit older at 26 – a bit of a cradle snatcher was the old boy!

Money was tight so we all lived with my widowed granny for the first few months of my life. Mum worked in the knitwear mills; knitwear is a big trade in the Borders and my dad was a joiner who worked for a small country joinery firm in Chesters village before eventually buying the business when the owner died.

My younger brother, Garry Alexander Hislop, was born in the same hospital as me on 28 July 1963, just 17 months after I was and we were very close right from the start. I loved having a brother.

Dad loved his bikes and was very friendly with the late, great Bob McIntyre, another Scottish bike racer and the first man ever to lap the Isle of Man TT course at 100mph. Dad raced between 1956 and 1961 on a BSA Gold Star and a 350cc Manx Norton. He travelled to all the little Scottish courses that don’t exist any more, such as Charter Hall, Errol, Crimond and Beveridge Park, including some circuits in the north of England such as Silloth – a track which would later have tragic consequences for my family.

He was a pretty handy racer in the Scottish championships but never really had the money to do it properly. He used to ride to meetings on his bike with a racing exhaust strapped to his back, fit it to the bike for the race then change back to the standard one and ride home again! That was proper clubman’s racing. As I mentioned earlier, my dad also raced at the Manx Grand Prix a few times usually finishing midfield but when mum became pregnant with me he packed in the racing game to support the family.

As a kid, I went to Hobkirk primary school. I remember being absolutely shit-scared, waiting for the bus on my first day of school because I was a very shy child and hadn’t mixed much with other kids since most of the time I just played with my little brother. Shyness is something I have mostly grown out of now but it was definitely a problem for me in the early days of my career.

I can’t remember much about primary school except that I always seemed to be sticking up for Garry in fights, particularly with a kid called Magoo who was always picking on him. My other outstanding memory of primary school was of Mr Thompson, the head teacher, who had a wooden leg, though I never found out why. Instead of giving us the belt when we were bad, he pulled our hair repeatedly! I clearly remember him telling me off and yanking the tuft of hair at the front of my head in time with his rantings. No wonder I’ve got no bloody hair left!

My secondary school was Jedburgh Grammar, but I was never interested in going there because I was a real out-door type, thanks to my dad’s uncles, Jim and John Wallace, having a farm. Almost every weekend I would cycle down to that farm and have the time of my life. I fed the sheep and the cows, picked the turnips and generally mucked in with the chores, then after that it was back to the house for a big farm breakfast and in the afternoons John and I would go shooting.

At that point, all I wanted to be when I grew up was a gamekeeper. I was like a little old man with my deerstalker hat with the ‘Deputy Dawg’ flap-down ear covers and a bloody big shotgun cocked over my arm. I used to feed up all the birds and ducks and make little hideouts round the ponds then come the shooting season I blew the hell out of everything that could fly – and some things that couldn’t.

I know that sounds cruel now but that was the norm in the country, especially back then, and boys will be boys after all. Having said that, I was a bit of a nasty little fucker when it came to things like that. I shot baby crows that had left the nest with my .22 rifle and kept the shotgun for the bigger birds and the nests themselves. I’m not particularly proud of it now but as I said before, it felt normal at the time.

On Sunday evenings I would cycle home again as late as I could get away with and dreaded going back to school the next day. I had pushbikes from a very early age but they were always hand-me-downs and were far too big for me. I never had any stabilizers either so I had lots of crashes because I was too small to reach the ground. My folks would hold on to me to get me going then seconds after they let me go there would be a big crashing noise, a yelp and a puff of dust as I hit the deck again. But I loved two-wheelers from the start, even when they were too big for me.

The first time I ever got a new bike was when my nana bought Garry and I brand new Raleigh Choppers for Christmas but they were just as dangerous as the too-big hand-me-downs. Choppers may have looked cool but they certainly weren’t designed for riding – they were bloody lethal. Garry once smashed his face to hell one night when he crashed cycling down a hill and he squealed in pain all the way home – the poor little bugger. We used to get into high-speed wobbles because the front wheels were so small and the high bars provided so much leverage that they made the effect worse.

Even back then we pretended we were riding motorbikes and like most kids at the time, we gripped playing cards onto the fork legs with clothes pegs so they ran through the spokes and made a noise like a motorbike. But showing an early aptitude for setting up machinery, I eventually found that cut-up bottles of washing-up liquid lasted longer than playing cards and made a better noise too!

Before we even had pushbikes, my mum says that Garry and I would sit in the house and pretend to be bike racers. We would be at opposite ends of the sofa over the armrests in a racing crouch, our little legs dangling over the side, and cushions under our chests acting as petrol tanks.

Apparently we fought over which racer we were pretending to be too and it was always Jimmie Guthrie or Geordie Buchan. Jimmie Guthrie was Hawick’s most famous son and one of the greatest names in pre-war motorcycle racing. He was born in 1897 and went on to win six Isle of Man TTs and was European champion three times when that title was the equivalent of today’s world championships. His admirers included none other than a certain Adolf Hitler who on one occasion even presented him with a trophy!

Jimmie was killed in a 500cc race at the Sachsenring in Germany in 1937 at 40 years of age and there’s still a statue of him in Hawick, as well as the famous Guthrie’s memorial on the TT course. Like I said before, Garry and I would argue over who was going to be Jimmy Guthrie and who was going to be Geordie Buchan, who was the Scottish champion at the time and also a friend of my dad. So in a sense, my first ever race was on a sofa and I think it finished in a dead heat with Garry!

Rugby is the big sport in the Scottish Borders and although I played it at school, I was never a big fan. In fact, I never liked football or tennis either and as for cricket – what the fuck is that all about? I’ll never understand the fascination with that game. It’s just grown men playing bloody rounders if you ask me. I was more into hunting and shooting things. My old Uncle John also taught me the art of fly fishing and I loved that too. I don’t do it any more but I suppose I’ll have to relearn it now to teach my own kids, Connor and Aaron.

However, I hope they never have to go through the experience I once had when I went sea fishing with my dad and Garry. Dad owned a little boat that we used to tow to the coast for a spot of line-and-rod fishing. On one occasion we took it to the Isle of Whithorn in Galloway and were anchored over some rocks on the Solway Firth doing a spot of rod fishing. It was a lovely hot, calm day so we didn’t have any life jackets on and everything was just perfect, the sun on our backs and the water lapping gently at the hull of the boat. But all of a sudden the peace was shattered by my dad screaming, ‘Get your bloody life jackets on boys, NOW! And get your rods in. QUICKLY.’ I turned to see what the hell could be causing all this panic and was startled to spot a huge dorsal fin heading directly for the boat. Bloody hell, I shat myself; it was a huge basking shark, more than twice the size of the boat (which was 16 feet long) and it was coming straight for us!

Although I didn’t know it then, basking sharks are harmless plankton feeders but they look just like great white sharks and are much, much bigger, growing to well over 30 feet. That’s pretty damned big when you’re a scrawny little four-foot kid. This all happened just two years before the movie Jaws came out and I’m pretty glad I hadn’t seen that film beforehand because I’d probably have been even more terrified and I was scared enough as it was. The shark went under the boat and I remember seeing its head emerging on the other side before its tail had even gone under – that’s how big it was. It just continued swimming away and that’s the last we saw of it, but it was a pretty scary experience – even though it was good to brag about later.

Garry and I were very close and I suppose we had to be really because there were very few other kids to play with. Obviously, we fought a bit as all boys do but we were the best of pals most of the time. We built tree houses and hammocks, messed about in the woods and by the rivers and had a real boys’ own childhood. We did used to pal around with a guy called David Cook, or ‘Cookie’ as we called him, who went on to become a 250cc Scottish bike racing champion, but he was about the only other kid we were close to.

Way before we ever got motorbikes, Cookie, Garry and I used to hone our racing skills in 45-litre oil drums. Two of us would squeeze into a drum and the third person would push it down a massive hill. It was brilliant fun to be in the drum but just as much of a laugh watching the other two getting beaten up as they bounced and rattled their way downhill, bones clattering all the way. Eventually we came up with a new addition to the game – a tractor tyre! This thing was bigger than all three of us but we managed to wheel it up the hill then I’d spend ages trying to squeeze my way inside it as if I was an inner tube. Once I was in, the lads would give me a mighty shove and off I went, bouncing and bouncing for what seemed like ages as the heavy tyre picked up speed on its way down the hill. That bit was all right – it was the slowing down followed by the inevitable crash that caused the many injuries. I’d get thrown out at the end as the momentum died out and I was usually really dizzy and disorientated from being spun round like a hamster in a wheel, so invariably I fell on my backside as soon as I tried to stand up.

One time I actually fell out of the tyre while it was still bouncing down the hill at speed and I crashed face first into a grassy knoll and bust my nose. It was bleeding and swollen and in a hell of a mess. I don’t know if it was actually broken, but to this day I’ve still got a kink in my nose and it was all because of that bloody tractor tyre.

As kids, our other passion was for bogeys, or fun karts, as people call them now. You know the type, a wooden base with four pram wheels and a rope for steering. We got really good at building them and even made one with a cab once. There was a steep downhill corner in the field next to our house which was good for learning to slide the bogeys on but we decided a bit of mud would help make it even slippier. I don’t know why we didn’t just soak it with water but instead we had the bright idea of pissing on that corner for all we were worth to make it muddy so we could get better slides! If we didn’t need to pee, we’d simply drink bottles and bottles of juice until we did – the more piss the better as far as we were concerned. We would eventually get the corner so wet that we had out of control slides and Garry once had a huge crash and ended up lying in that huge puddle of piss with several broken fingers.

It was a happy time for Garry and I, and it may have seemed idealistic at the time but in later years I realized the more negative effects my upbringing had on me. Because I was so isolated, I was very shy with other people. I still am today, to a certain extent, so I’m trying to encourage my kids to be confident and to mix freely with people so that they’re better equipped to deal with the big bad world than I was. Even now, I hate calling travel agents and bank managers or dealing with any ‘official’ phone calls like that, so if I can, I ask someone else to do it for me! I know that sounds pathetic, but it’s just the way I am.

There was another couple of kids, called Alistair and Norman Glendinning, with whom Garry and I sometimes played. They lived on a nearby farm called Doorpool. At the time, we were renting a cottage within the farm grounds which cost seven shillings a week (35 pence in today’s money), if my mum agreed to top up the water trough for the cows every day, which she did.

Once I remember having a big argument with Alistair Glendinning and I ended up throwing a garden rake at him. It split his face open and cut his head – he was in a right mess. I got a terrible bollocking for that but a few days later we were all playing happily together again. Kids don’t hold grudges, shame adults aren’t the same.

When I was nine years old, in 1973, my dad, as a former competitor, was invited to the Golden Jubilee of the Manx Grand Prix. When he got there he met up with Jim Oliver who owned Thomas B. Oliver’s garage in Denholm, just a few miles from where we lived. Jim was partly sponsoring a rider called Wullie Simson, who also lived near our home and my dad got to know him on that trip. It turned out that Wullie was a joiner like my dad but he’d quit his job when his boss wouldn’t give him time off to go to the Manx! My dad was getting a lot of work in so he offered Wullie a job, which was gladly accepted. Garry and I helped out at my dad’s workshop for pocket money and we liked Wullie straight away when he started there and we were always asking him about the racing.

Some two weeks after Wullie started his job at the workshop, my dad asked Garry and I if we’d like to go and watch some bike racing at Silloth, an airfield circuit just south of Carlisle. Too right we did! We were so excited at the prospect that we could hardly sleep. When Garry and I had been about five or six years old, we went with our nana and papa to stay in a caravan at Silloth. I remember hearing motorbikes howling away in the background and my grandma explained it was the bike racing over on the airfield. I ranted and begged her for so long to take us to see them that the poor woman ended up trudging with us for about six miles on the round trip to the airfield just so we could watch the bikes. There was a big delay in the racing because a rider was killed and my nana wanted to take Garry and I away from the track at that point, but I was having none of it. Apparently, I refused to leave the circuit until I’d seen the last bike in the last race go past. I obviously loved bike racing even way back then. That must have been in the late 1960s.

But I was 11 and old enough to really appreciate it properly by the time dad took me back to Silloth to watch another race and my most vivid memory of that meeting is of a guy in purple leathers, because everyone else was wearing black. Every lap he came out of the hairpin and pulled a big wheelie and I thought he was amazing. He was called Steve Machin and I’m now very friendly with his brother Jack though sadly later, Steve himself was killed on a race bike.

It was great to watch my dad’s mate Wullie Simson racing and he must have enjoyed our support because soon after that race, he turned up at our house in his van and pulled out a Honda ST50. It must have been an MOT failure or something because the engine was in pieces but my dad soon put it back together, got it fired up and that was it. From that moment on, Garry and I spent every spare moment riding that bike in the field surrounding the house. My motorcycling career had begun.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книгиВсего 10 форматов