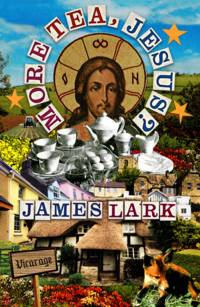

More Tea, Jesus?

Ted was well aware that the Cantique was beyond the capabilities of the St Barnabas church choir, but since there wasn’t a single piece of choral music that wasn’t beyond the capabilities of the St Barnabas church choir, he masochistically gave them repertoire that he was especially fond of, enabling the choir to ruin it for him.

‘Why don’t we start by singing through it?’ Ted suggested, several reasons instantly flitting through his mind. His face clouded over as the inevitable torture approached.

A voice quietly piped up in the altos. (Voices in the altos rarely piped up with any significant volume.) ‘Ted?’

‘What?’

‘Are we doing the French or the English translation?’

‘It’s French. It’s a bloody French piece. The clue’s in the title – the Cantique de Jean Racine. Are those English words? Have you ever met an English person called Jean Racine?’

‘It’s just—’ the alto bravely continued, ‘there are English words as well as French words in the music. There’s a choice.’

‘No,’ Ted impatiently growled, ‘there is not a choice because the music … is bloody … French.’

‘Okay,’ said the alto, ‘I wanted to check.’

‘Yes, thank you for checking,’ Ted retorted, his voice heavy with sarcasm. ‘Thanks for wasting everyone’s time. Let’s just start, shall we? Anne?’

Anne Hudson, installed in her usual position at the church organ, reluctantly looked up from her romantic novel, having reached a particularly engrossing and lurid section in which a stable boy called Jake had spilled a vodka and lime down his employer’s dress. ‘Yes?’

‘We’re ready. Can we start, please?’

‘What piece are we doing first?’ she unwisely enquired. It was completely impossible to see the choir stalls from the organ, the manuals having been situated in absolutely the worst place possible as far as sight lines were concerned; a small mirror had once allowed the organist to see the conductor’s left ear, but this had been stolen by a group of inebriated students during an unofficial and spontaneous late-night concert a couple of years earlier. Anne was, therefore, unable to see the precise cause of the minor explosion she could hear behind the pillar obscuring the conductor. In the silence that followed, she was tempted to go back to her romantic novel – Jake had been flirting with Lady Cardigan-Ainsley for several chapters now, and that the consequences of the (possibly deliberate) drink-spilling incident would be sensuous and erotic seemed inevitable.

Ted’s voice floated from behind the pillar, somewhat indistinctly due to the fact that he was crunching his teeth together. ‘We’re doing the Cantique de Jean Racine,’ it growled. ‘In French, in case you were wondering.’

The choir waited expectantly whilst Ted’s blood continued its inevitable progress towards boiling point. Finally, the organ began, and Ted started to beat time. It was three or four bars before he stopped. ‘Anne?’ he called. The organ continued to play. ‘Anne!’ he yelled, veins standing out in his neck. After a few more seconds, the sound died away. ‘What the hell are you playing?’ Ted demanded. ‘Because I’ve got the music in front of me, and what you’re doing bears no bloody resemblance at all to what Fauré wrote!’ There was no response. ‘Perhaps you think that Fauré’s version doesn’t quite work? Perhaps your own musical wisdom has given you some insights into the interpretation of these notes that I don’t have. Maybe you’re playing it in bloody English. What is it, Anne? Why don’t I recognise anything you’re doing?’

‘I haven’t had a chance to look at this one,’ Anne’s unrepentant voice answered from the direction of the organ.

‘Oh, I see!’ Ted said, ‘we do one anthem each week and you haven’t had a chance to look at the one we’re doing this week, right? That makes absolute sense.’ The choir waited, too familiar with this ritual to be embarrassed by it, and relieved that every second taken up by this argument was a second they wouldn’t be singing. ‘Then we shall have to manage with you making an utter cock-up of it, won’t we?’

Some choirs would have been shocked by Ted’s use of the word ‘cock’, but the choir of St Barnabas had grown accustomed to Ted’s standard rehearsal vernacular. The older members of the choir who might have found his colourful phraseology harder to cope with were all slightly deaf and assumed that they had misheard what he had said, though none of them had.

Ted wearily motioned in the direction of the organ for the introduction to begin again. After the silence, which was Anne Hudson guessing whether she was expected to play again, the organ came in with precisely the same accuracy as before – admittedly a fairly free interpretation of what Fauré had intended – and this time got a little further before Ted interrupted it.

‘Basses!’ he screamed. ‘Where the fuck were you?’

‘We didn’t know we were meant to come in,’ Harley Farmer explained, slowly.

‘We’re using this thing called music,’ Ted shouted, ‘that tells you what notes you’re meant to sing and when you’re meant to come in.’

‘But we couldn’t tell when that was,’ Harley calmly replied, ‘because we couldn’t tell what notes Anne was playing.’

‘Right, here’s some advice,’ Ted barked, ‘don’t listen to her, okay? Don’t listen to anything that woman plays because it’s always fucking wrong. I’ll bring you in. Watch me. Try to block the organ completely out of your mind. That’s what I’m doing.’ He took a couple of angry breaths then carried on. ‘I mean, think about my dilemma, I have to block out the organ and the bloody choir.’ He exhaled deeply, bringing his frustration vaguely back under control. ‘Let’s try again.’

The choir fumbled its way through the piece; it got progressively slower throughout and seemed to Ted to go on forever. When the final chord died away, he closed his eyes and didn’t speak for one and a half seconds.

Then he gave his considered appraisal. ‘That was without exception the most God-awful fucking noise I’ve ever heard in my entire life.’ The choir nodded in mute acceptance of this judgement. Ted generally told them this about everything they sang, although the exact expletives varied from week to week. ‘If I die tonight, I shall thank God with all my heart that he spared me from hearing that again,’ he continued. ‘Yes, Noreen?’ Noreen Ponty was holding her hand aloft, expectantly waiting to ask a question.

‘I wondered, Ted,’ she said, ‘how we’re pronouncing the word – er …’ She glanced at her music. ‘Er … “paisible”.’

‘Eh, what?’ barked Ted, ‘pay Sybil?’

‘No, er … “paisible”, on the third page.’

‘Good question, Noreen,’ Ted sarcastically answered. ‘Yes, that’s just what I was thinking, after listening to what probably counts as the worst crime ever committed against music – I thought, bloody hell, they don’t know how to pronounce “paisible”. What a bloody disaster.’

‘So … we’re saying “paisible”, are we?’

‘I couldn’t tell you what you are saying,’ Ted smiled sourly, ‘because I wasn’t listening to you at all lest it actually killed me.’ That this statement rather contradicted all of his previous judgements of the choir’s rendition went unnoticed except by a member of the choir who never made any noise at all, even to sing, so the discrepancy wasn’t pointed out. This was probably just as well.

‘What do you want us to say?’ Noreen persisted. Ted sighed.

‘Say it like … “passable”,’ he guessed.

‘Actually,’ Harriet Lomas contradicted him, with the knowing smile of one who has sung with the choir for several years and is therefore entitled to know more than the person directing it, ‘I think it’s more like “possible”, with a short vowel sound.’

‘Do you? And what do you think makes your opinion more correct than mine?’

‘Well,’ The knowing smile remained undiminished. ‘I spent five years working in France.’

This was the kind of mutiny that Ted resented most of all, because it was clearly entirely justified. ‘I don’t care if you were Fauré’s mistress,’ he sarcastically retorted, ‘I was a chorister in Winchester Cathedral choir. I also did French O-level.’

At this, Harriet’s smile withered abruptly. ‘But—’

‘Please shut up,’ Ted sighed, having had all of the argument he wanted to have. ‘We’ll run through it again, in the hope that one of you might have miraculously gained the ability to sing while I’ve been listening to this crap about French.’

Harriet glared at Ted through her large spectacles. She wasn’t going to argue back, because she was bigger than that. But she thought that Ted Sloper was the rudest man she knew and he had no right to talk to her like that.

‘What did you get?’ Gordon Spare asked Ted, suddenly.

‘What do you mean?’ Ted sighed.

‘What did you get in your French O-level?’

‘What does that have to do with anything?’ Ted angrily asked. (In actual fact he had failed his French O-level, and he certainly didn’t think this was the kind of detail that it was useful to bring to the discussion.)

‘I just thought,’ Gordon said, ‘if Harriet worked for five years in France – you know, five years …’

Ted closed his eyes. ‘I swear, this choir will be the death of me one day.’ He opened his eyes again and surveyed the dour group in front of him. ‘And as far as I’m concerned, the sooner that day comes, the better. Now can we run the bloody piece again, before we all die. Anne?’

There was another pause before Anne’s voice answered. ‘What?’

‘We’re going to run it again.’

‘Run what again?’ Jake and Lady Cardigan-Ainsley were in the middle of a particularly salacious scene, the vodka-and-lime incident having unfolded in exactly the direction Anne wanted it to, and she had rather been hoping her skills wouldn’t be called upon again during the rehearsal. They always seemed to spend so much time talking, anyway. ‘The Cantique, you stupid woman,’ hissed Ted. He rounded on the choir again and raised his hands to conduct. ‘It’s “passable”,’ he added, crossly, ‘even if your rendition of the piece isn’t.’

Bernard Lomas was a passionate person. His life was one of frustrated passions, an ongoing cycle of enthusiastic ideas passionately pursued for insufficient time to bear any fruit before a new infatuation developed.

As a young, ambitious man, his dream had been to earn a living from painting pictures of railway engines and transferring his artwork to crockery to be sold at unreasonably high prices, but circumstances had not worked in his favour and he had never managed to attain a secure enough position to put his strategy into action. This lack of security wasn’t so much a financial deficiency as an inability to paint; being a passionate man, he was also an impatient man (he told himself that the two characteristics naturally worked hand in hand), so he didn’t have the persistence to learn enough about painting to turn his dream into a reality. Instead, he continued to explore and discard different interests in the hope of finding his true vocation. He had gone through a phase of trying to start a career as a journalist, writing a couple of articles for amateur publications before getting bored and taking up the accordion. He had a brief obsession with tropical fish, which died as quickly as it had started along with most of the tropical fish themselves.

Bernard’s current obsession was with the art of cinema. Having spent half a year’s wages purchasing the best digital-video equipment with all the related software and essential appendages, he was determined to make the film that would propel him into the fast lane of the media world: a documentary about life in Little Collyweston. He hoped to exploit every link he had, including his wife’s strong connections with the church; he was aware that she sang in a choir, and gathered from her that it was rather good. Perhaps, he thought, he could make a documentary about the choir itself and sell it to the BBC – they had been rather short of ideas lately, after all.

Apart from his failure to make time to learn the necessary skills, the main problem with all of Bernard’s plans had been the need to earn money. To this end, he unwillingly worked for a government office in which he was supposed to encourage agricultural development. In essence, this involved a routine of regular meetings with tedious people in suits. Even the women wore suits these days. He couldn’t understand how the people he worked with could be so dull and he would spend many hours a day ranting about the unambitious state of affluent, middle-class society, whilst scribbling pictures of railways engines onto notepads and dreaming of his Little Collyweston documentary. Perhaps he could make a whole series – sixteen episodes, each lasting about an hour and featuring a different aspect of the village. The BBC would love that.

On this particular day, he had decided that, as an artist, he was excluded from the rules that governed ordinary, unambitious people, people who were part of the system, so he was justified in taking the day off work to familiarise himself with his new digital camcorder. So convincingly disease-ridden had his phone call to the office sounded that he was now half-wondering whether he might have potential as an actor. It was worth bearing in mind, he thought, for the best directors often acted in their own films.

He enjoyed a productive day at a nearby weir recording footage of water from as many different angles as possible and picturing himself as the world’s next Orson Welles. His evening had been spent trying to transfer the footage onto his computer. After more than four frustrating hours, he had concluded that he was missing a vital lead to connect his camcorder to the computer; technology was standing in the way of art, an injustice which enraged him, especially as he had many ideas of how the footage might be used in one of the documentary episodes, provisionally entitled Water. He was, as a result, in a particularly bad mood, and passionately so.

When his wife came home from her choir practice, he was so passionately moody that he forgot he was supposed to have spent the day at work. ‘I spent all day filming water,’ he told her, ‘all day, I’m telling you, and now I can’t even get it onto the computer because some pillock didn’t give me the right lead.’

It was fortunate for Bernard that Harriet Lomas was far too worked up herself to notice this disclosure of his truancy. ‘I had a terrible choir rehearsal,’ she announced, allowing herself to droop onto their sofa and flinging (with a degree of care) her spectacles onto the coffee table.

‘It’s not difficult, though, to make sure all the right leads are there when you sell something,’ Bernard complained, pacing the length of their living room. ‘I’ve got all this film of water and there’s nothing I can do with it. If you can’t get it onto the computer, you’re helpless – it’s like having a load of air and no lungs to breathe it with.’

‘I had a terrible choir rehearsal,’ Harriet repeated, adding particular emphasis to the word ‘terrible’. Harriet was different to her husband – she was not passionate, but controlled. She was also stoically single-minded and knew that to make her husband listen to her she simply had to repeat herself a sufficient number of times. Some wives would have found this process rather tedious, but Harriet was single-minded and controlled enough to patiently repeat herself as often as each situation required.

In this instance, Bernard had been declaiming about leads to himself for several hours already and had pretty much exhausted his rage on the subject, so he sat down next to his wife and asked about her choir rehearsal (wondering if her news might offer a new angle on the documentary). ‘Ted Sloper was extremely rude to me,’ Harriet told her husband.

‘Who’s Ted Sloper?’

‘He’s the choir director. I’ve told you about him before. He’s the rudest man I know and he swears a lot.’

‘Yes, I know about him, the one with the beard.’

‘He doesn’t have a beard,’ Harriet said. ‘He was telling us about French pronunciation and he obviously didn’t know a thing about French.’

‘I’m sure you said he had a beard.’

‘So I decided I should tell him the right way of pronouncing this word. Because it would be awful if the whole choir was singing the wrong pronunciation and thinking it was right, wouldn’t it?’

‘Who’s the one with the beard, then?’

‘There isn’t anybody in the choir with a beard,’ Harriet patiently explained, then paused thoughtfully. ‘Except for Mrs Sterp, but when you reach that age …’ She directed her thoughts back to the more important details of her diatribe. ‘Anyway, I told Ted Sloper how to pronounce this word in French …’

‘Is he French?’ asked Bernard, still catching up on the story’s earlier details.

‘No, I told you, he doesn’t know a thing about French. And when I told him how to pronounce the word, he said something about … he said that I was like Fauré’s mistress.’

Bernard’s face darkened. ‘He said what?’

‘No, it wasn’t that, he said … he said that he didn’t care if I was Fauré’s mistress.’

‘Who is this Fauré?’

‘He’s the man who wrote the music we were singing.’

‘Is he the one with the beard?’ Bernard asked, a new source of anger mounting inside him.

‘There isn’t anyone with a beard.’

‘Are you his mistress?’ Bernard asked.

‘Don’t be silly, he’s dead.’

‘Then what right,’ exploded Bernard, ‘does this Ted fellow have to accuse you of being his mistress?’

‘And when I argued with him, he told me to shut up.’

‘The French man? Fauré?’

‘No, Ted Sloper.’

‘The one with the beard?’

‘There isn’t anyone with a beard.’

Bernard stood up. ‘Where does he live?’

‘There’s no need, Bernard.’

‘Tell me where he lives!’ shouted Bernard. He was burning to take an evening’s worth of frustration out on this man, beard or no beard.

‘Calm down,’ Harriet ordered her husband. ‘There’s no point in doing anything about it now.’

Bernard sat down, reluctantly. ‘Tomorrow, then,’ he said. ‘Tomorrow I’ll go and speak to him. He’s no right …’

Thus satisfied by a husband’s righteous anger (which approximated a form of sympathy), Harriet picked up her spectacles from the coffee table and put them on, then looked fondly at Bernard. He was such a passionate person. No doubt he would have forgotten all about it in the morning.

Ted knocked moodily on the door of the vicarage. He wasn’t pleased to be there – by this time of the evening he was usually in the Green Baron and a drink of some kind was always necessary to wash away the taste of the choir rehearsal, but he was fairly sure Reverend Andy Biddle hadn’t asked him round to share a pint. Added to that, Ted always found encounters with the new vicar intensely depressing – it was something to do with the way he was always smiling.

Andy Biddle opened the door and smiled. ‘Ted!’ he beamed. ‘Thanks for coming.’

What was wrong with the man? wondered Ted. How could he spend so much time looking happy? He was supposed to be a Christian.

‘Won’t you come in?’ Biddle asked, and Ted reluctantly accepted the invitation, stepping into the warmth of the house.

‘Tea? I’d offer you a gin and tonic, but I’m completely out of gin. And tonic,’ Biddle laughed, then winced. ‘Ouch.’

‘What?’

‘I … er … broke my tooth the other day. It hurts when I laugh,’ Biddle chuckled cautiously.

Why? thought Ted. The man’s in pain and it’s still something to laugh about. This relentless enthusiasm was depressing Ted even more.

‘Tea will do,’ he gloomily said, trying to suppress his body’s desperate need for a pint of beer. He followed the vicar into the kitchen, feeling the insipid details of the house drain him of his little remaining resilience. Lots of pastel shades and nondescript watercolours – all new since Biddle’s arrival. Previously, the house had at least radiated some kind of life, having been not so much decorated as left to evolve its bold and frankly hideous décor (Biddle’s predecessor had been quite a different man who certainly would have had some gin).

Biddle reached down two yellow mugs from a cupboard and started to boil the kettle. ‘How’s the choir?’ he enquired cheerfully.

‘Awful,’ Ted replied, wondering if Biddle had asked him round for purely social reasons, and if so, when he could expect to leave.

‘Oh?’ Biddle’s face dropped a little, but not enough to make Ted feel any happier. ‘What’s the problem?’

‘No talent,’ Ted responded. ‘There’s not the slightest bit of talent amongst the lot of them. None at all.’

‘Ah. Right.’ Biddle chuckled, uncertainly. ‘Well – I’m not sure that there’s an easy solution for that one.’ Ted just stared back grimly, so Biddle added humorously ‘Except perhaps napalm!’

He quickly repented of the comment, hoping that he hadn’t offended his choir director; he apologetically put on a serious face in case he had.

‘They’re so unresponsive,’ Ted sighed, ‘I could insult them to their faces and they wouldn’t notice.’

‘I sometimes feel like that about congregations!’ Biddle laughed, then winced again.

‘You should see a dentist about that.’

‘I, er … I have an appointment with a dentist tomorrow.’ The kettle clicked and Biddle poured hot water into the mugs. ‘Milk?’

‘Yes. Two sugars.’ Biddle dutifully stirred sugar into one of the mugs, then carried them through to the living room. ‘I don’t think they realise how important music is to me,’ Ted continued, following Biddle. ‘If they did, they wouldn’t do what they do to it.’

‘The work you do with the choir is very much appreciated, Ted,’ said Biddle, gesturing towards one of his armchairs. Ted sat down miserably, feeling ever more trapped in an undesirable situation. ‘I know how much you put into it, and …’ He laughed again, which caused him another jolt of pain that almost made him spill his tea. It was hard enough remaining cheerful in front of Ted Sloper, without this toothache. ‘The choir is getting better every week,’ he lied.

‘You think so?’ Ted asked, raising an eyebrow knowingly.

‘I’m – not a musician, obviously …’ Biddle swallowed a chuckle before it had a chance to cause him any more pain, wondering why everything he was saying sounded so insincere this evening. ‘But if there’s anything I can do to make things any – er – easier, for you …?’

‘Got any napalm?’ Ted asked. Biddle laughed, graciously. Repeated back at him, his joke sounded incredibly tasteless, but at least Ted had taken it in the spirit it was intended – which was obviously not literally.

In actual fact, Ted thought that it sounded like a good idea.

‘How old is Gerard Feehan?’ Biddle suddenly asked. Ted frowned.

‘Not sure. Why?’

‘I just wondered.’

‘He sang with the choir years ago. I was trying to get some trebles into it. He was hopeless, of course. But still better than the tone-deaf old biddies singing at the moment …’ He put his head back and looked at the ceiling. ‘What would I give for a few trebles in the choir … you can’t get ’em these days, of course. Kids don’t do singing. It’s hopeless. Hopeless.’

‘So how long ago did Gerard sing in your choir?’ Biddle pressed.

‘Oh, years ago.’ Ted sat up again. ‘Young Feehan would be about twenty-two now, I’d say. Completely wet, though – always was a queer lad.’

Biddle nodded thoughtfully. ‘I get the impression he could do with getting away from his mother.’

‘We could all do with getting away from his mother,’ Ted said.

‘She does have quite a … forceful personality,’ Biddle chuckled.

Ted was now thoroughly fed up with the vicar’s unnecessary happiness, and still none the wiser about why he had been summoned there. They sipped at their tea wordlessly for a few moments, Ted wondering if this really was intended to be a social invitation – a chance for the new vicar to bond with his choir director. He braced himself for a miserably unexciting and teetotal evening, moving his eyes from the vapid watercolour of a windmill opposite him to the desk in the corner of the living room, a lamp lighting up a disarray of paper and books and a glowing laptop computer. ‘Writing another recipe?’ he enquired.