The Inside Story of Viz: Rude Kids

Arthur 2 Stroke

Another positive effect of punk was the emergence of fanzines, small DIY music magazines – usually the work of one obsessive individual – that were hawked at gigs or sold through independent record shops. My brother Steve had put me and Jim in touch with a new Newcastle fanzine that was looking for cartoonists. When we met the editors at the Market Lane pub in town we were dismayed to find they were all hairies, and their new magazine – Bad Breath – was going to be a ‘rock’ fanzine. I drew a cartoon about a punk band called Angelo’s Nonstarts for their first issue, but when I saw the finished magazine I wished I hadn’t bothered. It was a feeble orange pamphlet with very little content, badly designed too, but the worst thing about it was the tone of the editorial. It took itself so fucking seriously. There was an article about Lou Reed, and an earnest review of a pub gig by The Weights. It was all such a load of wank. Jim and I had been toying with the idea of producing our own magazine, a proper one this time with more than one page, and Bad Breath was so bloody awful it inspired us. We wanted to produce a comic that was also a fanzine, and the only artists we wanted to write about were Arthur 2 Stroke and the Noise Toys. The Gosforth Hotel would also be the ideal outlet for selling this magazine – and it would give us an excuse to talk to Gosforth High School girls – so we decided to take our idea to Anti-Pop. Whether we were looking for advice and encouragement, or merely an excuse to visit their office, I can’t quite recall.

The Anti-Pop office was in the Bigg Market, in a run-down building full of small rooms with glass-panel doors – the kind of office suites where private detectives sit drinking whisky and waiting for their next mysterious client to walk through the door. Their room was up on the third floor, wedged between a hairdressing salon and a derelict former pools collecting agency. We knocked and nervously entered. The room was tiny, like a short corridor with the door at one end and a sash window at the other. Already it was full of people. There was a solitary desk, a chair, and a built-in cupboard running along one wall which was being used by half a dozen or so people as a communal seat. All of the Noise Toys seemed to be there, plus their slightly dim roadie Davey Fuckwit. Arthur 2 Stroke himself was perched on the windowsill, gazing at a shit-covered shoe lying on the ledge outside and repeating the word ‘guano’ to himself over and over again. It looked like a form of meditation. ‘He’s thinking of ideas,’ someone explained. Jim and I were a little intimidated finding ourselves in the presence of so many pop idols, but we somehow managed to blurt a few words out about our proposed magazine and I held out a folder of our cartoons as a sort of peace offering. These were passed around the room and met with grins of approval. Turning to Andy Pop I asked if they would allow us to sell the magazine at their gigs in return for a free advertisement on the back cover. This was immediately agreed. Then came an unexpected bonus. Martin, the singer with the Noise Toys, said that he was a cartoonist and offered to contribute to the new magazine.

Andy Pop

Our project had got the green light – the only problem now was that we didn’t have a clue how to put a magazine together. Someone at Anti-Pop suggested approaching the Free Press for help. The Tyneside Free Press described themselves as a ‘non-profit-making community print co-operative’, whatever one of those was, and Jim and I went to see them at their print works in Charlotte Square. I explained to the man on the front desk that we wanted to produce a magazine but had no idea how to put it together, technically speaking. He was most helpful and began by explaining a few of the basics. For important technical reasons we couldn’t have ten pages as I’d suggested, we’d have to have eight or twelve. And if we had twelve pages they would be printed in pairs, page 12 alongside page 1, and page 2 alongside page 11, etc. This was called page fall. I was fascinated. Then he talked about the artwork, explaining how the ink is always black and how greys are made out of lots of little black dots. Finally, he produced an estimate for printing 100 twelve-page magazines. This came to a staggering £38.88, in other words almost 40p per copy. He must have noticed my face drop and quickly pointed out that the more we printed, the cheaper it would become per copy. He mentioned that a T Rex fanzine they’d printed recently had sold out of 100 copies in a week and had since been back for a reprint. Encouraged by this I asked him to price for 150 copies, and this came to £42.35. It was four quid more, but it brought the cost of each comic down to 28p each. It still seemed a lot of money so I shopped around for some other prices. The Co-operative Printers in Rutherford Street quoted me £153, and Prontaprint on Collingwood Street said they’d do the job for £156. I decided to stick with the Free Press.

Jim and I had quite a collection of old cartoons in hand, but all of our work was small and I needed a lot more material to fill twelve pages. Martin’s contribution was more of a collage than a cartoon, a three-dimensional conglomeration of paint, glue, print and paper featuring an angry metal bloke in a hat, called the Steel Skull. Jim wrote a tabloid-style exposé about the Anti-Pop movement, and I received another written contribution from a newspaper reporter in Kingston upon Thames called Tim Harrison. Shortly after leaving school I’d got bored and put a pen friend advert in Private Eye. The first person who replied was Tim Harrison, and I’d been corresponding with him ever since. But when Tim’s contribution for my new magazine arrived – a girly piece of grown-up satire suggesting that Prince Charles was gay – it was totally out of keeping with everything else I’d gathered. I didn’t want to hurt Tim Harrison’s feelings – at least not until now – so I decided to use it anyway.

We still had to choose a name for the new magazine. At one point Jim’s favoured title had been Hip because he liked the slogan, ‘Get Hip!’ Another proposal was Lump It, as in ‘If you don’t like it (and you won’t like it) you can Lump It’. But in the end I went for the catchier and much more concise The Bumper Monster Christmas Special, which just seemed to roll off the tongue. Viz was an afterthought and sprang from an experiment I’d been doing with lino cuttings. My dad had some spare lino tiles left over after tiling our living room floor and I’d been carving bits of them with chisels, rolling them with ink and then pressing them onto paper in a vice. While playing around I came up with the word VIZ, which was easy to carve, consisting only of straight lines and no curved letters. That’s what I always tell people anyway. Unfortunately the lino blocks, which I still have today, don’t say VIZ, they say Viz Comics, with several curvy letters. So fuck knows where the name came from. I can’t remember.

I assembled the artwork on a card table in my bedroom. It was a bit like doing a jigsaw, trying to slot everything together neatly. There were still a few gaps to fill, so I asked my brother Simon if he fancied doing a cartoon. Simon had recently formed his own noisy youth club band, Johnny Shiloe’s Movement Machine, but he took time out from his budding acting and pop career to do a three-frame cartoon containing sex, cake and vomiting. It was a terrific combination. Eventually all the gaps were filled and on Wednesday 28 November 1979 I took a half-day off work to deliver the artwork to the Free Press. They said it would be ready on Friday the following week.

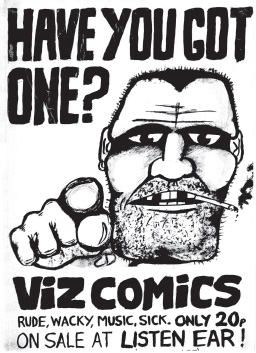

The original Viz Comics lino print

A bit like those twats out of Spandau Ballet, me and Jim made a big song and dance about Viz before the first issue had even been published. Pre-launch publicity included sticking posters up around Newcastle Polytechnic Students’ Union and lino-printing Viz Comics logos onto a roll of typewriter address labels. These were stuck randomly on windows, contraceptive machines, lamp-posts and bus stops around the Gosforth Hotel and Newcastle Polytechnic areas, and we somehow managed to stick one high on the façade of the Listen Ear record shop on Ridley Place. That one was still visible from the top deck of the 33 bus for several years afterwards. Unlike those twats out of Spandau Ballet, we weren’t students, and so we weren’t allowed inside the Students’ Union buildings. The Poly Students’ Union entertainments officer was a horrible bloke called Paul something-or-other who wore fashionable knitwear and had blond, swept-back hair. We called him Mr Fucking McGregor because every time he caught us fly-posting he’d chase us out of the building muttering various garbled threats about putting us in a pie. But every time he chased us out we’d come back even more determined. Eventually the object of the exercise wasn’t to promote the comic, it was purely to antagonize that daft bastard. This spell of aggravated promotional activity earned us a rather ironic reputation as an ‘anti-student’ magazine which lasted some time. Jim and I hated students. If townies like us wanted to get into either the University or the Polytechnic to see a band we had to stand at the door looking humble and beg passing students to sign us in. We were envious of their cushy, low-price accommodation, their cheap booze, cheap food, cheap and exclusive live entertainment, and the fact that they were surrounded by young women. It was the male students we hated, not the girls.

I took Friday 7 December off work and went with Jim to collect the finished comic from the Free Press. When we got there, the first thing that struck me was how small the box was. I was expecting a stack of cartons, not one flat box. But 150 very thin comics didn’t take up much room. It was raining as we carried them the short distance from the Free Press to the Anti-Pop office. There was nobody there so we retired to a nearby café, Country Fare, where, over a cup of tea and some cheese scones, we sat and read our very own comic. The ink was blacker than black and the paper was creamy and smooth. It made the cartoons look different, more clean and deliberate, almost as if someone else had drawn them. The spines of the comics were neatly folded, and the staples were shiny and new. We sat and admired them for ages. For some reason I’d decided to give away a ‘free ice cream’ with every issue and this meant taking the comics home and spending the best part of the weekend lino printing pictures of ice creams and then stapling them onto the back pages. I’d taken a few advance orders from friends, and the first person to pay for a copy of Viz was a Gosforth High girl called Karen Seery. But it was on Monday 10 December at the Gosforth Hotel that Viz was officially launched.

Myself, Jim and Simon all went along, although Simon was only fifteen and risked being fed to the landlord’s dogs if he was caught on the premises. I decided to take thirty copies of the magazine as I couldn’t imagine selling any more than that in one night. Early in the evening we positioned ourselves on the landing outside the function room door and started offering them to passers-by. None of us were natural salesmen and a typical pitch would be, ‘Funny magazine. Very wacky. Twenty pence.’ People weren’t interested. 20p was a bit steep for a twelve-page black-and-white comic. The Beano was twice as thick, colour, and half the price in those days. There were no takers. One passing Gosforth High girl called Ruth snarled and called me a capitalist. That hurt. I’d paid the print bill out of my own pocket with no prospect of getting my money back. Even if I sold out I was losing 8 pence on every copy. It was hardly capitalism at that stage, love. Things weren’t looking too good until a little man with a gingerish beard and a scarf, more of a social worker than a student or punk, came skipping up the stairs. He looked a bit right-on, the kind of guy who’d give some kids doing their own thing a break. ‘What’s this?’ he said with exaggerated enthusiasm. He had a quick look, smiled, bought one and disappeared into the function room. Not long afterwards people started coming out and buying copies. Once they’d seen someone else reading it and laughing, suddenly they all wanted one. It was the first sales phenomenon I’d ever witnessed, and it was a phenomenal one. Soon we were running out of comics and a friend called Paul, who had a car, offered Simon a lift back home to pick up some more copies.

Skinheed Poster

As well as the Gosforth I also sold copies at a Dickies gig at the Mayfair later that week, and the following weekend at a Damned gig in Middlesbrough. There was only one shop that stocked the first comic, Listen Ear on the corner of Ridley Place and John Dobson Street in Newcastle. The little man behind the counter, who was short and far too old for his comical punk attire, seemed rather non-plussed at the idea of stocking yet another fanzine, but reluctantly agreed to take ten copies on sale or return. He placed them inside the glass counter and under the till, where nobody could see or reach them. ‘If I leave them on the counter they’ll be nicked,’ he said. As well as hawking the comic around pubs and student discos in Newcastle I made a couple of futile efforts to reach a wider audience. In February 1980 I invested £3.25 in a classified ad in Private Eye:

Viz Comics. Very hilarious indeed.

20p plus SAE to 16 Lily Cres, Newcastle/Tyne.

At about the same time I wrote a hopelessly optimistic letter to a magazine distribution company called Surridge Dawson Ltd. and received my first rejection letter:

Dear Mr Donald

Thank you for your letter of 1st February in connection with the distribution of your comics. Firstly, as you are most probably aware, the comic market in the United Kingdom is very competitive indeed, and would be difficult to break into without reasonable financial backing.

From our point of view as national distributors, we would require a regular publishing date and also need to be selling about 10,000 copies per issue to make it a viable operation. To be quite frank, at present I do not think you are in a position to consider distribution on a national scale, but nevertheless we will give the matter further thought on sight of a complete copy of your magazine.

Yours sincerely

T. H. Marshall

General Manager Publishing Department

I hadn’t dared send them a complete copy, just a few selected highlights, because I knew full well that if I’d sent the whole comic it would have gone straight in the bin.

With the benefit of hindsight it was probably a wee bit early to be thinking of a commercial deal, but I was getting some grassroots distribution thanks to a few enthusiastic individuals each taking a handful of copies here and there. A Newcastle University student called Jane Hodgson took twenty copies to sell to her mates and my pen friend Tim Harrison also took ten copies. Then at the end of February I got my first big break. Derek Gritten, a bookseller in Bournemouth, had spotted my ad in Private Eye and wanted to see a sample of the comic. If he liked it he said he would order twenty-five copies, my biggest order so far! My £3.25 investment looked to be paying off, and I rushed Mr Gritten a copy of the comic by return . . . but he didn’t reply.

Never mind. The first comic had been surprisingly well received by the public and I knew that the next one could be much better. By now a second issue was underway on the card table, but this time I was taking care to plan it better, make it look neater and more attractive. Jim had drawn a couple of new cartoons, Simon had done another cartoon with vomiting in it, and Martin Stevens had come up with a brilliant new character called Tubby Round. For music content I’d interviewed a fellow DHSS employee called Dave Maughan about his very serious prog rock band Low Profile – and then written an entirely different story in which they became a disco band. And Jim had written about a new Anti-Pop artist who was rapidly becoming a legend.

Anti-Pop’s first record release, a double A-sided single by the Noise Toys and Arthur 2 Stroke (‘Pocket Money’/‘The Wundersea World of Jacques Cousteau’) had been getting air play on John Peel’s show, but a new Anti-Pop album called Anna Ford’s Bum by Wavis O’Shave was causing a bigger stir both on radio and in the music press. Wavis O’Shave wasn’t a comedian and he wasn’t a singer. He definitely wasn’t a musician either. He was a sort of cross between Howard Hughes, Tiny Tim and David Icke. He was never seen at the Gosforth Hotel and I’d only ever caught a glimpse of him once in the Anti-Pop office, when he didn’t speak at all. To promote the album he only played one gig – at the Music Machine, Camden, in March 1980 – and he didn’t even turn up for that. A heavily disguised Arthur 2 Stroke went on in his place. None of his fans knew what Wavis looked like, so there were no complaints. (Wavis would become better known in later years as The Hard, a bizarre character who made brief appearances on The Tube, hitting his hand with a hammer and saying ‘I felt nowt’.)

Viz comic No. 2 went on sale in April 1980. This time I really pushed the boat out and printed 500, and gave away a free balloon with every copy . . . stapled to the inside back cover. The print bill was £66.67, plus another £4.91 for balloons purchased from fancy goods specialists John B. Bowes Limited, late of Low Friar Street, just round the corner from the Free Press. In those days you never had to walk more than 100 yards to buy a bag of 500 balloons. Viz wasn’t going down too well in Surrey. Having struggled to shift ten copies of issue 1 in Kingston-upon-Thames, Tim Harrison cut his order down to six. But sales were up elsewhere. The Listen Ear record shop took an astounding seventy-five copies, Jane Hodgson took thirty, and Jim’s dad Jack Brownlow, a progressive school teacher and a thoroughly nice bloke, bought twenty-five. My dad didn’t buy any though, largely because he didn’t know Viz existed. By now he was out of work and spending all his time looking after my mum. Both of my parents were blissfully unaware of the comic’s existence, and I wanted to keep it that way for as long as I could.

Issue 2 was clearly a big improvement on issue 1 so I sent an unsolicited copy to Derek Gritten, the bookseller in Bournemouth who’d gone very quiet since receiving issue 1. He wrote back confirming that he hadn’t liked the first one, but the good news was that he did like issue 2 and he promptly ordered twenty-five copies. Despite this promising progress the vast majority of the 500 comics had to be sold in Newcastle by hand, and at nights I’d walk from pub to pub in Jesmond selling comics on my own. I didn’t like going into pubs alone, and I hated cold selling. It was totally against my nature. But something drove me to do it. I did it obsessively, a bit like train-spotting, going from room to room asking every single person if they wanted to buy a comic. The aim wasn’t to sell comics, it was simply to ask everyone. Once I’d asked everyone then I could go home happy, even if I’d sold none. On one of these fleeting runs, through the Cradlewell pub, I inadvertently offered a comic to the new Entertainments Officer from the Polytechnic; a big, bald bloke called Steve Cheney. ‘So . . .’, he said, standing up and turning round to face me, ‘this is the new anti-student magazine I’ve been hearing about, is it?’ His predecessor, Mr Fucking McGregor, had obviously briefed him on our activities. ‘It’s not anti-student at all,’ I told him with a convincing smile. It wasn’t actually, only me and Jim were. ‘Here, have a read and see for yourself.’ I gave the big, baldy twat a free copy and he smiled, said thank you and sat down to read it while I made my escape.

I preferred selling comics when there were two of us. Jim didn’t actually do much selling – he preferred drinking and watching the bands, and the women – but he provided physical and moral support. That could come in handy in the Students’ Union bars where every cluster of students contained at least one gormless twat just waiting for an opportunity to show off to his mates. Occasionally things turned nasty, like the time I foolishly walked into the ‘Agrics” bar at the University and some stumpy, little fat-necked student grabbed about a dozen comics out of my hand, tore them in half and threw them all up in the air above my head. Then he just glared at me as if to say, ‘What are you going do about it?’ I looked at him as if to say ‘Erm. . . nothing, I suppose,’ then sidled away like a coward.

I hadn’t shown the comic to anybody at work. They were all regular, working-class sorts of people. They liked drinking in the Bigg Market and disco dancing, so I thought it might be a little left-of-field for their tastes. But gradually they began to find out about what I was doing and started asking for copies of the comic. When I eventually took some in, to my surprise and delight they all liked it too. All except the old ladies, that is. People laughed out loud, passed them around, and asked for copies of the next issue. This was a revelation to me. Ordinary people found it funny as well as rebellious youths and student types.

As well as crossing socio-economic divides, the geographical spread of sales was also expanding. So far Viz was strictly a Newcastle, Bournemouth and ever-so-slightly Kingston-upon-Thames publishing phenomenon. There was a conspicuous lack of outlets in the capital. Luckily Arthur 2 Stroke had a brother called Tim who lived in South London and Tim volunteered to do some footwork, taking the comic to Rough Trade records and Better Badges. Both shops agreed to stock it. I’d also placed two more ads in Private Eye, one in ‘Articles for sale’, advertising issue 2 for 32p including postage, and the other in the ‘Wanted’ column, offering £1000 for a copy of the first issue. Eager to spread the message I’d also sent copies of issues 1 and 2 to the local newspaper, and this resulted in our first ever press cutting. On 10 April 1980, beneath the headline, ‘A comical look at Newcastle social problems’, the Newcastle Evening Chronicle described Viz as ‘a new comic which is not the usual light revelry, but more a social commentary’. According to their reporter Viz was ‘taking a wry look at society in the form of cartoon strips’, and he summed up by describing it as ‘Sparky for grown-ups’. It was all strangely flattering. They didn’t mention the shit drawings, the foul language or the violent and unimaginative cartoon endings. This was my first ever dealing with the tabloid press, and I’d soon discover how flexible their approach to a subject could be.

Celebrated television producer Malcolm Gerrie, who would later launch The Tube, was in those days producing a dreadful ‘yoof’ show on Tyne-Tees TV called Check It Out. Getting on ‘Checkidoot’, as it was known locally, was the height of ambition for many local bands who assumed that stardom would quickly follow. In reality it didn’t work like that. If they’d looked at the statistics they’d have realized that an appearance on this cheesiest of yoof shows would virtually guarantee them obscurity for the rest of their careers. But Check It Out seemed like an ideal place to publicize Viz, so I bombarded Malcolm Gerrie with copies of the comic and accompanying begging letters. Eventually he invited Jim and myself to his office at the City Road TV studios. Gerrie was a surprisingly geeky-looking bloke with buck teeth, fancy geps, wild eyes, a pointy hooter and ridiculous corkscrew haircut. As if one such face wasn’t bad enough, the wall behind him was plastered with photographs of himself grinning at the camera while clinging to the shoulders of various pop luminaries. Could this be Michael Winner’s illegitimate son I wondered. Jim and I were disappointed by what Gerrie had to say. He explained that he liked the comic very much but he couldn’t possibly consider it for his TV show because of the expletive nature of some of the contents.