Peggy Guggenheim: The Life of an Art Addict

PEGGY GUGGENHEIM

The Life of an Art Addict

ANTON GILL

To Marji Campi (who started all this)

with admiration, gratitude and love

London, New York, Paris, Venice; 1997–2001

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

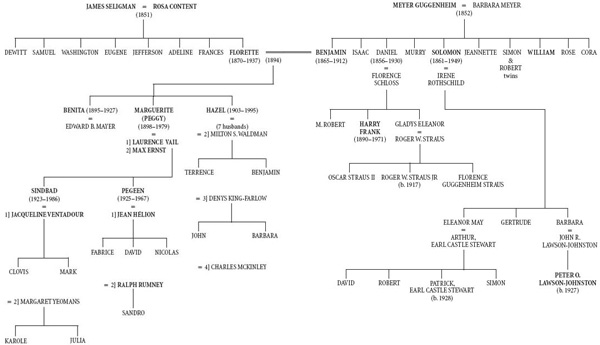

Family Tree

Foreword

Prelude

Part 1: Youth

1: Shipwreck

2: Heiress

3: Guggenheims and Seligmans

4: Growing Up

5: Harold and Lucile

6: Departure

Part 2: Europe

7: Paris

8: Laurence, Motherhood and ‘Bohemia’

9: Pramousquier

10: Love and Literature

11: Hayford

12: Love and Death

13: An English Country Garden

14: Turning Point

15: ‘Guggenheim Jeune’

16: Paris Again

Intermezzo: Max and Another Departure: Marseilles and Lisbon

Part 3: Back in the USA

17: Coming Home

18: Art of This Century

19: Memoir

Part 4: Venice

20: Transition

21: Palazzo

22: Legacy

23: ‘The last red leaf is whirl’d away …’

Coda

Acknowledgements

Source Notes

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Praise

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Family Tree

Foreword

This book is made up of material derived from private and public archives and collections, published works, unpublished works, letters, diaries, interviews, gossip, e-mails, telephone conversations, videotapes, faxes, websites and so on. Despite the fact that the subject is recent, a number of discrepancies of spelling have cropped up in proper names. Where that has happened, I have used the version most commonly used by others.

I have not tampered with usage, grammar or spelling in direct quotations from original material such as letters, though I have tidied up typographical errors – for many years Peggy Guggenheim used an ancient typewriter with a faded blue ribbon, and her typing was not accurate. I have left eccentricities of spelling alone (Peggy habitually spelt ‘thought’ ‘thot’, and ‘bought’ ‘bot’), and have provided an explanation only if the level of obscurity seemed great enough to warrant one. Round brackets in quoted passages belong to the passage; glosses within such passages are in square brackets.

Titles of artworks in Peggy’s collection are generally the same as those used by Angelica Z. Rudenstine in her catalogue of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. Other paintings and sculptures are given the names they’re most commonly known by.

I’d like to express my thanks here at the outset to all who helped. A lot of people had a profound personal contact with Peggy, and shared their memories of her with me generously. I am most grateful to them – their names are in the acknowledgements at the end of the book. I have had to be selective in the use of some tangential detail for reasons of both focus and of space. Readers interested in further exploration of the background to this book are referred to the bibliography. Inevitably what I have written will lead to a certain amount of disagreement. Some of the material conflicted, and some was clogged with gossip and rumour. I can only say that to the best of my ability I have checked all the matter I have used for correctness, and that I have tried to keep speculation to a minimum. I thank Marji Campi, Barbara Shukman and Karole Vail for looking over the manuscript, but I alone am accountable for any errors. I have not, however, consciously sought to mislead or offend anyone in this record of the life of a complex, anarchic, remarkable woman.

Anton Gill

London, 2001

Prelude

A Party

‘Her obduracy in contention and her warmth in friendship, her generosity and her stinginess, her plunges into gloom and wholehearted abandonment to laughter, her puritan streak and her reckless addiction to the erotic were all contradictions of the essence of her personality.’

MAURICE CARDIFF, Friends Abroad

The rain, which had not stopped for a week, ceased in the late afternoon of 29 September 1998, so that by the evening the flagstones in the garden were dry. The heat and the humidity relented too, so that as the crowd gathered the atmosphere and the temperature were perfect.

The garden was that of the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, an eighteenth-century pile in Dorsoduro, on the Accademia bank of the Grand Canal in Venice, between the Accademia Bridge and Santa Maria della Salute, close to where the Canal Grande debouches into the Canale di San Marco. The palazzo is exotic. It was never finished. It only has a sub-basement and one storey, with a flat roof that doubles as a terrace; but the garden is one of the largest in Venice. The trees are huge. When Peggy Guggenheim owned and lived in the palace, the garden was muddy and overgrown, and the sculptures planted in it – the bronze trolls of Max Ernst, the minimalist, organic forms of Arp and Brancusi – inhabited it as mysterious beings might lurk in a wood, waiting for the traveller to come upon them unaware.

Several hundred guests were gathering that Tuesday evening twenty years after her death in a more manicured space: neatly flagged and gravelled, with the sculptures openly displayed. Not all of the sculptures now belong to the art collection which Peggy Guggenheim brought here in the late 1940s. Many are part of the collection of the Texan collectors Patsy and Raymond Nasher.

The crowd has assembled in the electrically lit, mosquito-free night. The garden is full. Dress ranges from super-elegant to T-shirt and jeans, but everyone is stylish. Le tout Venise is here to mark the opening of an exhibition commemorating the centenary of Peggy’s birth. Organised by one of her granddaughters, the exhibition has come here from New York, where it opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Solomon was Peggy’s uncle, though their two art collections were separate entities during most of her lifetime. The granddaughter, Karole Vail, is the only Guggenheim grandchild to work for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. She is among the guests, in a Fortuny dress, elegantly echoing the Fortuny dress Peggy often wore. Her sister Julia and her cousins are there too – six of the seven surviving grandchildren. Mark has not come. Fabrice died in 1990.

Philip Rylands is the curator of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. He has been in charge since the palazzo became a public gallery in 1980. Philip is English, and originally came to Venice from Cambridge University to research a doctoral thesis on Jacopo Palma (il Vecchio). He makes a speech in impeccable Italian. During it, as the light through the trees throws changing shadows on the people below, Mia, Julia’s daughter, the only one of Peggy’s great-grandchildren present, twenty-one months old, clambers onto Untitled (1969) by Robert Morris – a huge rectangle of steel balanced on a massive section of steel dowelling, stretched horizontally on the ground. Mia runs up and down. Her activity turns a few heads.

After two hours, people have begun to filter away, and in another hour the garden will be empty. In a corner a stone slab set into a wall marks the resting places of Peggy’s ‘beloved babies’ – fourteen little dogs, until almost the end all pure-bred Lhasa Apsos, which in a series of generations shared Peggy’s life in the palace. Next to it is another plaque. On it is written: ‘Here rests Peggy Guggenheim 1898–1979’.

The party in 1998 filled the garden. Eighteen years earlier, on 4 April 1980, only four people were present for the interment of Peggy’s ashes. She had died an isolated death just before Christmas the previous year.

Although Peggy’s claim to fame is as one of the foremost collectors of modern art of the first half of the twentieth century, her ‘offstage’ life as a restless combination of wanderer and libertine has attracted so much gossip, obloquy, scandal and delight that it has overshadowed her influence as a patron of painters and sculptors. When she was at the peak of her career, feminism was in its infancy and, apart from the Suffragette movement, not organised on any major scale. Men took it for granted that they had precedence over women, and it would be hard to find a more sexist bunch than the male artists who flourished between 1900 and 1960. Peggy took on their world with a mixture of low self-esteem and aggression, aided by money. She couldn’t enter that world as an artist – a difficult task for any woman at the time – but she could use her money to buy a position in it. In her endeavours she never quite found herself, but she supported three of the most important art movements of the last hundred years: Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract-Expressionism.

It took Peggy some time to come to modern art. She was twenty before she held a contemporary painting in her hands, at the photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s boundary-breaking 291 Gallery in New York City – a picture by Stieglitz’s wife-to-be, Georgia O’Keeffe. If she was flirting with Bohemia as early as that – the introduction to Stieglitz stemmed from work in a cousin’s avant-garde bookshop – it would be another twenty years, one husband and many lovers later before she started work on her own account.

At twenty-one, Peggy came into the first slice of what was a relatively slender fortune. In the years following the First World War, Europe beckoned young Americans, and Peggy, used to childhood holidays on the Continent, and for other reasons too, was among the first to go. There she plunged into the world to which she was to belong for the rest of her life, and in which she was to be a star.

The Second World War forced her, as a Jew, to retreat to America. There, in New York, she created a gallery the like of which had not been seen anywhere before, and through it and the salons – if such a word can be applied to the whiskey-and-potato-chips parties she held – in her house overlooking the East River on East 51st Street, she created a forum where young American artists could meet and confront the old guard of European modern art in exile.

The war over, and another marriage unhappily over too, she returned to Europe, and made her home in Venice. It was there that she set about the task of consolidating her collection. She’d been a flapper, she’d been a profligate, she’d been a Maecenas, she’d been a wife, she hadn’t been much of a mother. Now it was time to become a grande dame. Inside, there had always been an inquisitive and lively girl who had never been able to find love.

When I first visited the Peggy Guggenheim Collection I was struck by the refreshing contrast to the splendours of Renaissance and Baroque art in which Venice is so rich. It was a palate-cleanser after which one could return happily to the glories of the Scuola San Rocco or the Frari. Peggy herself, hesitating to name any picture in her own collection as her favourite, did have a favourite painting: The Storm by Giorgione (c.1505), in the Accademia, a stone’s throw from her palazzo. She once said she would swap all of her collection for it.

The festa to mark her one hundredth birthday would have amused Peggy by its contrast to her lonely departure from this world, and it would have touched her that so many people were there. She would also have been appalled at the expense.

Later that evening it began to rain again.

1 Youth

‘I was born in New York City on West Sixty-Ninth Street. I don’t remember anything about this. My mother told me that while the nurse was filling her hot water bottle, I rushed into the world with my usual speed and screamed like a cat.’

PEGGY GUGGENHEIM, Out of This Century (1979)

CHAPTER 1 Shipwreck

Things had been going badly for Benjamin Guggenheim for a long time. The fact that his marriage was falling apart was something he’d got used to a while back, and, as he admitted to himself, there had been ample consolation – though through it all a nagging lack of satisfaction – for the rapid cooling of his relationship with his wife. The business was another matter. He’d left the family firm eleven years earlier, in 1901, full of injured dignity at what he saw as the high-handed attitude of most of his brothers, determined to go it alone and show them: after all, the expertise he’d picked up in mining and engineering should have stood him in good stead. And, to be fair, it had. Wasn’t his International Steam Pump Company responsible for the lifts that now ran all the way to the top of the Eiffel Tower? And Paris hadn’t been a bad alternative, this past decade, to a loveless, even inimical, New York. If it weren’t for his daughters, Benita, Peggy and Hazel, the three unlikely products of his and Florette’s rare moments of passion (informed by duty) over the first eight years of their union, he might well have cut loose altogether.

But the business was going downhill, and he could see no way of turning it round. He’d never been a businessman, any more than he’d been an enthusiastic student – though the family never failed to remind him that he was the first of the first-generation American Guggenheims to go to university. The failure of his business was worse than the failure of his marriage. Excluded from the family concern, how could he ignore the vast strides that it had made since he’d left at the turn of the century, drawing a modest $250,000 a year from his then-existing interests? Now, in April 1912, he’d decided to return to the States. It would be Hazel’s ninth birthday on the thirtieth. He’d be home for that. And he might drum up some extra capital once home, too, though asking his brothers for a loan would be a long shot, and his wife’s money was too tied up for him to reach, even if he’d had the courage to ask for it. At least no one in the family but himself knew how bad things were. Mismanaged capital, shaky investments and an extravagant lifestyle were to blame.

He’d married Florette on 24 October 1894. She was twenty-four, he was twenty-nine. He’d played the field beforehand, and he was handsome enough to have attracted a better-looking partner; but she was a Seligman, and therefore, though her family looked down on his, a real catch. The Seligmans didn’t have the kind of money the Guggenheims had, but they had the New York cachet the Guggenheims needed, and at that time Ben was still a paid-up member of the family.

Since the birth of his youngest daughter, Ben had spent more and more time in France, looking after his business interests and several mistresses. He’d hardly seen his children in the past year, and not at all in the last eight months, though a letter survives from him to Hazel, written from Paris in early April 1911, which testifies to the affection he had for them. It also indicates that he wanted to see his wife again, though its tone is more dutiful than sincere:

Have just received your letter, am sorry it takes so long for the doll to get through the custom house but when he does reach you I am sure you will like him. We had quite a lot of snow and cold weather yesterday so you see that even in Paris we sometimes are disappointed. However it is again pleasant today and I think we will soon see the leaves on the trees. Tell Peggy I have just rec’d her letter of the 30th Mch but as I just wrote her yesterday I shall not write again today. Tell her also I was very glad to receive this her [?]kind letter and hope that she and you will frequently find time to write me. I am writing Mummie asking if she wants me to rent a beautiful country place at Saint Cloud near Paris. If we take it she can invite Lucille and [?]Doby, and can remove there for July.

With much love from your

Papa

He missed his children, especially the younger two, who adored him and were rivals for his affections. His oldest, Benita, named for him, was almost seventeen – already a young woman, self-possessed, a little cool, beautiful, unlike her mother, but showing signs of wanting nothing more than the moneyed, inactive life of bridge, tea-parties and gossip that Florette enjoyed. Ben was well aware that Florette regarded him as a loser. She had her own means, but she liked money, and she liked acquiring it more than spending it.

What a pity they hadn’t produced a son. But that was something the Guggenheim clan was seldom capable of.

The closest Ben had to a son was his nephew Harry, one of the five boys the seven brothers had managed to produce to carry the family name forward – though Ben’s sisters also had sons. Ben had had lunch with Harry in Paris on 9 April, shortly before leaving for Cherbourg to pick up his ship for the States. Harry was a shade strait-laced already at twenty-two, but Ben talked to him about his business affairs, playing down his difficulties; Harry’s father was Daniel, the most dominant, though by no means the richest, of Ben’s brothers. Ben steered clear of personal observations. A few years earlier, when Harry was fourteen or fifteen, Ben had got into hot water by offering him this piece of advice: ‘Never make love to a woman before breakfast for two reasons. One, it’s wearing. Two, in the course of the day you may meet somebody you like better.’

Shortly before the meeting with Harry, Ben had a problem to deal with. The ship he was booked on, with his chauffeur, René Pernot, and his secretary-valet, Victor Giglio, was suddenly unable to sail, owing to an unofficial strike over pay by her stokers. Ben was one of a number of irritated passengers who were forced to find alternative berths, but after a number of wires to London, New York and Southampton, luck appeared to favour him. He managed to get two first-class cabins, for his valet and himself, and a second-class berth for his chauffeur, on the White Star Line’s new flagship, RMS Titanic, which was making her maiden voyage, stopping at Cherbourg on the evening of 10 April, en route from Southampton to New York via the French port, and Queenstown (now Cóbh) in Ireland. It wasn’t cheap – the first-class cabins cost $1520 each one-way – but the ship was very fast, at the cutting edge of technology and, in first class at least, the last word in elegance. Ben, used to the good things in life even in adversity, was pleased that the switch had had to be made. And when he looked at the passenger list and saw in what august company he’d be travelling, he wondered whether the manner of his crossing the Atlantic might send a message to his brothers that he was doing better than he actually was.

Ben was the fifth of seven brothers. Only William, the youngest, might have been sympathetic, but William had cut loose from the family firm at the same time as Ben, and while he shared Ben’s love of the good life, he was a self-absorbed young man. Like Ben, he had become a ‘poor’ Guggenheim. Each of the two brothers had given up a capital interest of $8 million when they’d left the business – something else Ben had kept secret from his wife.

Nevertheless, as he settled into his cabin on B deck, Ben could reflect that ‘poor’ was a relative term. He still had plenty of money by most people’s standards, and his older brothers, as far as he could see, had yet to make serious money themselves. In his forty-seventh year, Ben still had time to turn his fortunes round.

But it was not to be. We don’t know where Ben was at 11.40 p.m. on the night of 14 April, but the chances are that he had already retired to his cabin. Wherever he was, he would have felt the faint, grinding jar that came from the bowels of the ship at that moment. He may well have seen the iceberg as it glided past. But like most on board, he did not feel any concern. After all, the Titanic was supposed to be unsinkable. Relying on this, and ignoring ice warnings which had come from other ships in the area throughout the day, the captain, Edward J. Smith, a veteran sailor making his last voyage before retirement, had continued to sail virtually at full speed. Egged on by J. Bruce Ismay, White Star’s president, he was attempting to set a new transatlantic record.

At about midnight, by then joined by Giglio, Guggenheim was being helped into a lifejacket by the steward in charge of that set of eight or nine cabins. Henry Samuel Etches urged Guggenheim against the latter’s protests to pull a heavy sweater over the lifejacket (few aboard, cocooned from the elements in the well-heated, brilliantly-lit liner, had any idea of how cold the North Atlantic was), and sent him and his valet on deck. As first-class passengers, their places in lifeboats were assured. However, in the next hour or so, as confusion mounted and it became clear that women and children might be left aboard the sinking ship as the inadequate (and in the event woefully underfilled) lifeboats began to be cast off, Benjamin Guggenheim and Victor Giglio did a stylish and brave thing: they returned to their cabins, changed into evening dress, and then set about helping women and children into the boats. Ben is reported to have said, ‘We’ve dressed in our best, and are prepared to go down like gentlemen.’

The rest of the story may belong to the corpus of Titanic myth, but it’s reasonable to believe some of the details of Ben’s last moments. However, as neither Giglio nor the chauffeur, René Pernot, survived either, it is impossible to verify them. The first-class cabin steward, Etches, was ordered to take an oar in a lifeboat, and did survive. He subsequently made his way to the St Regis Hotel in New York, where several members of the Guggenheim family had apartments, and asked to see Ben’s wife, as he had been entrusted with a message from her husband. Florette, who already knew that Ben was missing, was too grief-stricken to see him; he was received by Daniel Guggenheim. The encounter was widely reported, but the fullest account of Etches’ story appeared in the New York Times on 20 April:

… I could see what they [Ben and Giglio] were doing. They were going from one lifeboat to another, helping the women and children. Mr Guggenheim would shout out, ‘Women first’, and he was of great assistance to the officers.

Things weren’t so bad at first, but when I saw Mr Guggenheim and his secretary three-quarters of an hour after the crash there was great excitement. What surprised me was that both Mr Guggenheim and his secretary were dressed in their evening clothes. They had deliberately taken off their sweaters, and as nearly as I can tell there were no lifebelts at all.

It is possible that Etches concocted a tale of heroism with an eye to a reward of some kind from the wealthy family; but in view of the fact that Ben and his valet were not the only men who went down with the ship rather than take what could have been seen as the cowardly expedient of getting into lifeboats, it seems unlikely. Other newspapers reported that among the prominent people on board, John Jacob Astor IV, of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, President Taft’s military aide, Major Archibald Butt, and Isidore Straus of Macy’s department store also helped others into the boats and thus sacrificed their own lives. Etches added that Ben had told him, ‘If anything should happen to me, tell my wife in New York that I’ve done my best in doing my duty,’ and that ‘No woman shall go to the bottom because I was a coward.’ Significantly, Bruce Ismay, who did save himself, was profoundly affected from the moment he was taken aboard the rescue ship, Carpathia. As the chronicler of the disaster, Walter Lord, records in his book A Night to Remember: ‘During the rest of the trip Ismay never left [his] room; he never ate anything solid; he never received a visitor … he was kept to the end under the influence of opiates. It was the start of a self-imposed exile from active life. Within a year he retired from the White Star Line, purchased a large estate on the west coast of Ireland, and remained a virtual recluse until he died in 1937.’