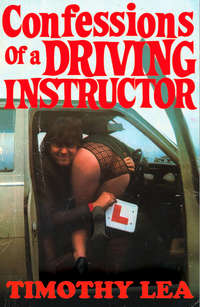

Confessions of a Driving Instructor

“Oh God! Even my far from successful marriage had progressed beyond that hoary old male chestnut.” Mrs. D.’s tone is as contemptuous as I had expected it to be. “Why should you have complete freedom to take sex just whenever you want it, whilst your little woman is supposed to sit at home and keep your supper warm?”

I have now decided that the kittens look more like small, fretful tigers jostling each other to escape and get at me. I am prepared for this eventuality.

“You mean to tell me,” I say seriously, borrowing one of J.C.’s successful argumentative devices, “that if your old man came in now and saw us—um, er—” (the indecision is intentional; I don’t want to sound too sure of myself) “making love, he wouldn’t mind?”

“No, of course not. No more than if he found me enjoying a bit of quiche lorraine.” (I don’t understand what she’s on about, but I imagine it must be French for a muff job. Outspoken lady, isn’t she?) “It’s no more than an appetite and as such, it can be controlled.”

“And if it was the other way round, you wouldn’t get annoyed?”

“Good heavens, no.”

“Then what went wrong with your marriage?”

“I found out I didn’t love him any more. It had nothing to do with sex. I was seven years younger than him and I changed—he didn’t. Suddenly I found we had nothing in common.”

I can sense that I have to get things moving pretty quickly, otherwise we’re going to end up having a natter that only needs Adam Faith and the Archbishop of Woolwich to get it on Sunday evening telly. I am still lying down and I want to bring her down to my level. It’s no good with her leaning against the bedroom door. I can’t just get up and grab her, because that is not my style. There is still some lager in my glass so I put it down beside me and then promptly knock it over.

“Oh, sorry. I am a clumsy berk.”

“It doesn’t matter; there’s a cloth in the bathroom.”

She goes out and I dab ineffectually at the stain with my handkerchief until she comes back. Then she’s on her hands and knees beside me and her delicious tits bounce up and down whilst I ache to close my hands around them. Her vest hangs open, and it is like looking into a sackful of apples. “Do something!” shouts the voice inside me. The soft down of hairs on her forearm glistens gold and matches the curls gently caressing the smooth, white valleys behind her ears. “Do something!” She gives one last stain-dispersing rub and sits back on her haunches. The outline of her pants now runs across her stretched skirt like an extra seam. She takes a deep breath and there’s no doubt about it, she’s a real knock-out. “Do something!” The message gets home to me and I lean forward for what is intended to be a gentle, respectful kiss, capable of interpretation as mute admiration rather than slow rape. Trouble is that she suddenly leans forward at the vital moment and nudges me in the mouth with her temple. I taste blood immediately and she doesn’t make things any better by laughing. Nothing bright and breezy leaps to my lips and, sensing my discomfiture, she gives me a light kiss on the cheek.

“I’m sorry—” she begins, but when a Lea’s passions are roused and his pride stung, tidal waves are like a kid’s widdle. I grab her above the elbows and pull her on to my mouth. She struggles a bit and then goes limp so that I can release the pressure on her arms and send my finger up to stroke her cheeks. I suck her lips and her tongue darts against mine. She is rubbing those fantastic tits against my chest and her fingers claw underneath the belt of my jeans. I may have misread the signs but I don’t think she is going to start hollering for a cop.

I kiss her eyelids and with the delicacy of a master surgeon run my fingers along her backbone, dwelling momentarily on each firm protuberance. Her vest is cramping our style and I tug it upwards until the delicious breasts bound into my eager hands and I can soothe the fretting nipples with my kindly caress. Such a shape they have, and so firm. The vest must go and she writhes rhythmically like an athlete winding up to throw the discus, before slipping it over her shoulders. Unimpeded, I now drop my mouth and browse between her breasts, near suffocating in their rich, firm fullness. My hands scout for the hook on her skirt and tug it open, down with the zip, and I can feel the soft sheen of her pants. Her fingers are not idle and she fumbles with my belt, grumbling under her breath. I flip over on my back and slip down my trousers, pants, shoes and socks like a snake shedding its skin. She lies across my chest and her hand tip-toes down to explore between my legs. Deliciously naked and warm in the sun-filled room, I kiss her hard and send my tongue deep into her mouth so that her hand tightens around my fullness and her body squirms against mine. I have had enough of games and even vein and muscle in my body throbs to be at her.

“I want you inside me.”

She tears the words from my mouth and slowly turns on to her back like a frivolous cat, her half-parted lips hinting at the pleasure to come. For a second I savour her and then I am between her legs, pulling down her skirt and slowly removing her pants—women love having their knickers taken off—before softly gauging her readiness with my fingers. She gives a little gasp and stretches out her hand imploringly.

“Please,” she says. “Please put it in.”

Maybe it is an hour later, maybe longer. I don’t know. All I do know is that the sun is still shining, the room is still warm and I have been asleep. Mrs. D. is dozing beside me and I am looking straight into the eyes—or rather eye—of a scruffy teddy bear.

“Penny!”

The voice is loud and male and does not belong to the teddy bear—not that it is coming from much further away.

“Penny! Where the hell are you?”

Mrs. D.’s eyes open and then open a whole lot more. Her head bounces off the floor and she swallows half the air in the room.

Now, at this moment, I should have remembered that Mrs. D. and her husband were separated and that he wasn’t the jealous type anyway. I should have lain back and called out, “We’re in here, old chap. Won’t be a sec. Why don’t you fix yourself a gin and T. and we’ll be right down?” and he would have coughed apologetically and said, “Gosh, I’m most awfully sorry. Hope I didn’t disturb you, what? See you in a few mins.” Then I could have had Mrs. D. again and gone downstairs to talk about how the soil around here was lousy for lupins.

But, of course, I don’t do any of those things. Maybe it’s the look in Mrs. D.’s eyes or maybe it’s the size of the voice outside, or maybe it’s just instinct; but anyway, I’m half way across the room as the door knob starts turning. I pause pathetically, considering snatching up a few clothes, and then launch myself on to the ladder. As I swivel round, my eye captures the scene like a camera. Door flung open, bloody great rugby type filling the space it occupies, Mrs. D. cowering with her pants in one hand and the other draped across her tits. Mr. D. (I have no reason to suppose it is anyone else) sinks the scene in one gulp and bounces Mrs. D. across the room with a belt round the side of the bonce which would have stopped Joe Frazier.

I feel like telling him that I agree with him entirely and that he has all my sympathy, but I don’t think he wants to talk to me. His eyes flash towards the window and as my head drops out of sight I see him reaching for something. This turns out to be a hobby horse, as I find when he swings it at my head like a mace. The expression on his face would scar your dreams for years.

“I’ll kill you, you bastard,” he screams, and he doesn’t have to go on about it—I’m convinced. I’ve hardly had time to rejoice that I’m out of range than he changes his tactics. I’ve got the extension on and there’s a long drop to the ground. Mr. D. decides to speed up my journey and, jamming the hobby horse against the ladder, starts to push it away from the house. Like a prick, I hang on for grim death and scream at him instead of sliding. What a way to go! Stark bollock naked in the middle of Thurston Road! I see Dunbar’s face contorted in a self-satisfied effort and for a moment the ladder trembles. Then I’m going backwards, paralysed with fear, and the house is growing in front of me.

I try to jump and the next thing I know is this god-awful pain in my ankle and the feeling that all the breath has been dug out of my body with a spade.

I’m sprawled across the centre of the road, screaming with pain and fear, Mrs. D. is howling, the neighbours’ windows are slamming open, cars are squealing to a halt, and suddenly a quiet residential street seems like Trafalgar Square on Guy Fawkes night. I’m glad to see everyone, because any second I’m expecting Mr. D. to come bursting through his front door to finish the job. It’s amazing how the great British public react at a moment like this. They are interested all right, but not one of the bastards makes a move to help me. I might be a tailor’s dummy for all they care.

To my surprise, Mrs. D. is first to my side, and she’s alone, thank God. She drapes a blanket over me and that encourages a few helpmates to get me on to the pavement.

“What a load of crap about your husband,” I snarl. “If that was your husband.”

“Yes, yes,” she says, beaming round at the neighbours, who, observing her black eye, are no doubt putting two and two together and scoring well. “I’m sorry about that. He’s phoning for an ambulance now.”

“Sure it isn’t the morgue?”

“No, no.” She pats my arm and smiles again. “I’m sorry. I really am.” I close my eyes because I’m feeling sick, dizzy and knackered. Bugger the lot of them. When I open them again, it’s as I’m being lifted into the ambulance. Mrs. D. follows me in and gives my hand an affectionate squeeze.

“It was wonderful,” she says.

I won’t tell you what my reply was, but the ambulance man nearly dropped me on the floor.

CHAPTER TWO

It turns out that my ankle is broken in more places than a Foreign Secretary’s promises and they keep me in hospital for three days. I have a private room, which surprises me at first until I find out that it is courtesy of a certain Dr. Dunbar—small world, isn’t it? I make a few inquiries and it seems that this party has taken his wife and kids on a camping holiday to the South of France, so he isn’t around to be thanked. You could knock me down with a feather—or half a brick, if you had one handy. So Cupid Lea strikes again! What a carve-up! Why wasn’t I in the marriage guidance business? I might not be able to do myself any good, but I was obviously the kiss of death to the permissive society.

One of the advantages of a private room, apart from the fact that the other buggers couldn’t nosh your fruit, was that it gave you an uninterrupted crack at the nurses, and some were little darlings. I’ve always been kinky about black stockings and Florence Nightingale, and with one pert red-head the very presence of her thermometer under my tongue was enough to raise the bedclothes a couple of inches. There is nothing more randy-making than lying in bed with sod-all else to do but fiddle about under the bedclothes and by the end of my time, the nurses had to come into the room in pairs and my arm had grown half a foot grabbing at them. It didn’t do me any good, although I did corner the red head in the linen cupboard on my last morning and pin her against a pile of pillow cases with my crutch (the one you prop under your arm). I had just got one hand into that delicious no-man’s-land between stocking top and knickers (I hate tights) when Sister came in looking like a scraped beetroot and I had to say goodbye quickly. All very sad but life is full of little might-have-beens.

Eight weeks later it was time to take the plaster off and I was bloody grateful because every berk in the neighbourhood had used it as a scribbling pad to demonstrate his pathetic sense of humour. Word of my escapade had got around and there were a lot of cracks about ‘Batman’ and ‘Peter Pan’ which I found pretty childish.

I hate going to the Doctor because the waiting room smells of sick people and most of the magazines are older than I am. It is cold and badly lit and the stuffed owl in a glass case looks as if you’d only have to give it a nudge for all its feathers to fall out. Everybody seems healthy enough but I have a nasty feeling that underneath the clothes their bodies are erupting in a series of disgusting sores covering limbs held together by sellotape. Behind the serving hatch a parched slag of about 182 dispenses pills and indifference. In such an atmosphere I wonder why the N.H.S. doesn’t dispense a do-it-yourself knotting kit and have done with it.

When I get in to his surgery, Doctor Murdoch attacks my plaster as if gutting a fish that has done him a personal injury. From the look of him one would guess that he had just returned from a meths drinkers’ stag party. The sight of my ankle causes his prim lips to contract into walnuts and I can sympathise with him. The object we are both staring at looks like a swollen inner tube painted the colour of a gangrenous sunset.

“What do you do?” he barks.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean if you’re a ballroom dancer, you’d better get down to the labour exchange.”

“It’s going to be alright, isn’t it?” I whine. I mean, what with heart transplants and artificial kidneys you expect them to be able to mend a bloody broken ankle, don’t you?

“You’ll be able to walk on it, but I won’t make any promises about the next Olympic Games,” says Murdoch who must be a laugh riot at his medical school reunions.

“I’m a window cleaner,” I pipe.

“You were,” says Murdoch. “That ankle has been very badly broken. You can’t risk any antics on it. I’m amazed we’ve got it together as well as we have.” I’m speechless for a moment. All those windows, all those birds. I could weep just thinking about it. What are they going to do without me? What am I going to do without them?

Added to that, there is the money.

“Are you positive?” I gulp.

“Absolutely. Of course, you don’t have to take my advice but you’d be a damn fool to get on a ladder again.”

So there I am, redundant at 22. Lots of blokes would envy me but there is a crazy streak of ambition in the Leas and I’m too patriotic to go on National Assistance—at least for a few years yet. What am I going to do?

Broken-hearted, I manage to get pissed and return to the family home. As I have already indicated relations with Dad have been strained since Sid’s departure and my accident has not drawn forth the sympathy one could expect from a father figure. I suspect that this may be due to some of the rumours that have been circulating. “Look Mother,” he sings out as I come through the door. “It’s the Birdman of Alcatraz!”

This is really witty for Dad and besides confirming my suspicions is an unkind allusion to a few months I once spent at reform school.

“Shutup, you miserable old git!” I say.

“Don’t raise your voice to me, sonny,” says Dad, “otherwise I’ll start asking you when you first began to clean windows in the all-together. Got a nudist camp on the rounds, I suppose?”

Dad and Doctor Murdoch would make a wonderful comedy team, and I’m wondering what Hughie Green’s telephone number is when Mum chips in.

“Do leave him alone, Dad, he’s told you enough times what happened.”

“Oh, yes, Mother. I know all that. He was stretched out on the roof, wasn’t he, having a little sunbathe. Then this bloke opens a window, dislodges the ladder. Timmy grabs at it, slips, loses his balance and does a swallow dive into the street. Sounds very likely, doesn’t it?”

“I really can’t be bothered—” I begin.

“I suppose that bird got a black eye when you landed on top of her?”

“I wonder what your excuse is going to be, Dad?”

“Don’t adopt that tone with me, Sonny Jim. I could still teach you a few lessons if it came to the pinch.”

“Well, prove it, or shut up.”

I mean it, too. Every few weeks or it is probably days now, Dad and I are squaring up to each other and sooner or later I am going to dot the stupid old bugger one. Nothing happens this time because mum throws a tantrum and sister Rosie arrives with little Jason.

“I can’t stand it, I can’t stand it,” Mum is wailing when little dribble jaws shoves his jam-stained mug round the door and her mood changes faster than a bloke finding that the large lump in the middle of his new cement path is his mother-in-law.

“Hello darling,” she coos. “Who’s come to see his Grand-mummy, then? Ooh, and what a nasty runny nose we’ve got. Doesn’t naughty mummy give you your lovely cod liver oil, then?”

Honestly, Rosie must feel like belting her sometimes. She still exists in a world of cod liver oil, cascara and milk of magnesia. Open your bowels and live might be her motto.

Mum and Rosie go rabbiting on and little Jason rubs his filthy fingers all over the moquette. Just like old times. I haven’t had a chance to tell anyone about my problem, and nobody would be interested, anyway.

“How are the lessons going, dear?” says Mum.

“Oh, smashing Mum. I’ve got this lovely fellah. Very refined, lovely even white teeth. I think they’re his own. You know what I mean?”

Mum shakes her head vigorously. “Yes dear, some of them are very nice. I’ve thought about learning myself, but your father will never get one.”

What are they on about? I’ve never known Rosie to acknowledge the existence of any other bloke than Sid.

“He’s ever so gentlemanly and he never shouts at me. Everything is very smooth and relaxed.”

“That’s the secret, dear,” agrees Mum. “If you were doing it with Sid he would probably start getting at you. I’m told you never want to take lessons with your husband. Can you imagine what your father would be like?”

They nod enthusiastically.

“Bloody marvellous, isn’t it?” says Dad, letting me in on the secret. “For thirty years I struggle and sweat to support a family and never even sniff a motor car. Now every bleeder has one and your mother starts saying she wants to take driving lessons.”

“Yes Dad.”

I’m not really listening because suddenly I’ve got this feeling that fate—or whatever you like to call it—is trying to tell me something. Become a driving instructor! Why hadn’t I thought of that before? It would be ideal. I can’t hop about on my leg too much and as an instructor I’d be sitting on my arse most of the time, telling some bird to turn left at the next traffic lights. It would be a doddle. And what opportunities to exploit my natural talents! If Mum and Rosie could be aroused, just imagine the effect on a normal red-blooded woman! I’d seen all those ads and tele commercials—that’s where they had got the idea from. Tight-lipped, hawk-eyed young men ruthlessly thrusting home gear leavers with wristy nonchalance whilst, open-mouthed x-certificate “yes please” girls lapped up every orgasmic gesture. It was a wonder a bird could look at a gear stick without blushing. And the whole operation had so much more class than window cleaning. I’d seen them with their leather-patched hacking jackets, nonchalantly drumming their fingers against the side of the window. “Very good, Mrs. Smithers. You really are beginning to make progress. Now let’s pull off on the left here, and I’ll ask you a few questions about the Highway Code—”

“Oh Mr. Lea—”

“Careful, Mrs. Smithers, you’re drooling all over my chukka boots.”

I can see it as clearly as Ted Heath’s teeth. An endless procession of upside-down footprints on the dashboard.

Are you the guy that’s been a pushin’

Leaving greasemarks on the cushion

And footprints on the dashboard upside down

Since you’ve been at our Nelly,

She’s got pains down in her belly,

I guess you’d best be moving out of town.

That’s the way Potter the Poet tells it and that’s the way I can see it.

The rest of the day is background music and the next morning I am round at Battersea Public Library which is the source of all knowledge to the lower orders. I had been simple enough to imagine that you just slapped a sign saying “LEArn with LEA” on your car and you were away. But, oh dear me, no. Not by a long chalk. The lady with a frizzy bun and indelible pencil all round her unpretty lips soon throws a bucket of cold water over that one.

“You’ll have to write to the Department of the Environment,” she says coldly. Me writing to the Department of the Environment! I mean, it sounds so grand I hardly feel I have a right to. Maybe I should chuck it all in and get a job on the buses. But I do as she says and soon receive an AD154 (an official paid buff envelope which Dad snitches to send off his pools), an AD12, an AD13, and AD1 3L, two AD14’s and an AD1 14 (revised). My cup overfloweth. After poring over this lot till my eyes ache I work out that I have to get on the Register of Approved Driving Instructors and that to do this I have to pass a written and a practical examination. I will then be a—wait for it—“Department of the Environment Approved Driving Instructor” and you can’t get much higher than that, can you? D.E.A.D.I.—oh well, I suppose they know what they are doing.

Filling in the application form is a bit of a drag because there is a section about convictions for non-motoring offences and a request for the names of two people prepared to give references. I decide to come clean on the lead-stripping because, on the application form, they give you four lines for details of your offences and tell you to continue on a separate sheet if necessary, so they must be used to getting some right rogues. My criminal record will fit into half a line.

The references are more of a problem because you can’t use family (not that anyone, apart from Mum, would have a good word for me) and I am not on close terms with anyone else in S.W.12. In the end I make up a couple of names and give my sister’s address for one, and a block of flats where I know the caretaker for the other. Both of them get instructions to hang on to any mail addressed to the Rev. Trubshawe or Lieut.-Colonel Phillips R.A. and sure enough, both of them get a letter asking for a character reference.

I am dead cunning with my replies, even getting the Rev. Trubshawe to allude to my schoolboy indiscretion: “no doubt accounted for by his having strayed into the company of the wrong sort of boy”, whilst the colonel says I am a “damn fine type”. My little ruse seems to work because two weeks later I get a receipt for my £5 examination admission fee and am told where to report.

The first examination is the written one and I mug up all the guff they give me so I see road signs every time I close my eyes. I have never worked so hard in my life and I feel really confident that I’m going to do well. But—and that is one of the key words in my life—once again fate puts the mockers on me. This time it is in the crutch-swelling shape of the eldest Ngobla girl Matilda. The Ngoblas are our next door neighbours and, as their name suggests, are blacker than the inside of a lump of coal. Mum and Dad are very cool about it and would never admit to anything as unsavoury as racial prejudice but the Ngoblas are not on our Christmas card list and when Mum smiles at Mrs. Ngobla it’s like Sonny Liston trying to tell his opponent something as they touch gloves. For myself, I am not very fussed either way but I don’t have much to do with the Ngoblas, basically, I suppose, because I never have done.

My encounter with Matilda takes place when I am revising on the eve of my examination. Mum has gone to the bingo and Dad is at the boozer so I have the kitchen to myself and am reading “Driving” for the four hundred and thirty second time when I look out of the window and see Matilda prancing about on the lawn (which is what Dad calls the patch of dandelions by the dustbins). She has just achieved that instant transformation from schoolgirl to woman and with her pink woolly sweater and velvet hot-pants she looks decidedly fanciable. I can hardly believe that when I last saw her she was wearing a grubby gymslip and dragging a satchel behind her. It turns out that one of her kid brothers—there are about 400 of them—has lost his ball over the wall and I help her look for it whilst flashing some of the small talk that has made me the toast of Wimbledon Palais. I am glad to find, when she bends over an old chicken coop, that there isn’t a drop of prejudice in me. In fact, quite the reverse. I could board her, no trouble at all. She looks as if she has been poured into a black rubber mould and the sight is enough to give Mr. Dunlop a few ideas for new products, I can tell you.