The Frayed Atlantic Edge

During my morning on Eilean a’ Chlèirich I sought evidence of the people who once eked out livings in this most uncompromising spot. At first, wading through thick, ungrazed foliage, the island felt largely untouched. But I gradually began to see hints of human history shrouded by the plants: chunks of cut stone and roots of an old wall. The earliest human traces here are vestiges of stone circles from a time before written records: millennia over which imagination has freedom to roam. From a later age are scant remnants of Chlèirich’s time as an early Christian retreat; this was the period that gave the island its name yet it is unrecorded in any document from the time. Then there are foundations from structures built by a nineteenth-century outlaw whose banishment from the mainland was recorded in just one short sentence of Gaelic prose. But the island’s stones only really intersect with literary record with traces of the occupation by 1930s naturalists whose brief stay was immortalised in Frank Fraser Darling’s Island Years (1940).

Barely anything of any of these people’s endeavours stands above ankle height, yet Chlèirich is layered with past activity, where each successive wave of habitation has been so limited in scale that it hasn’t erased previous histories. Wandering its hollows and hillocks is therefore a historian’s or archaeologist’s fantasy. Indeed, what made Chlèirich feel wild was not just wind, rain and the sounds of the sea, but the sense of being amid remnants of human action that had been conclusively defeated by weather. Humans toiled here centuries ago and my back when I slept had been laid against their labour: the rocks I nestled among had been worked by people, before wind, rain, ice and lichen reclaimed them for the wild. Although the British Isles have no untouched wilderness, their wildness is all the more remarkable for its entanglement with history: this journey would be an exercise in the art of interpreting the intertwining.

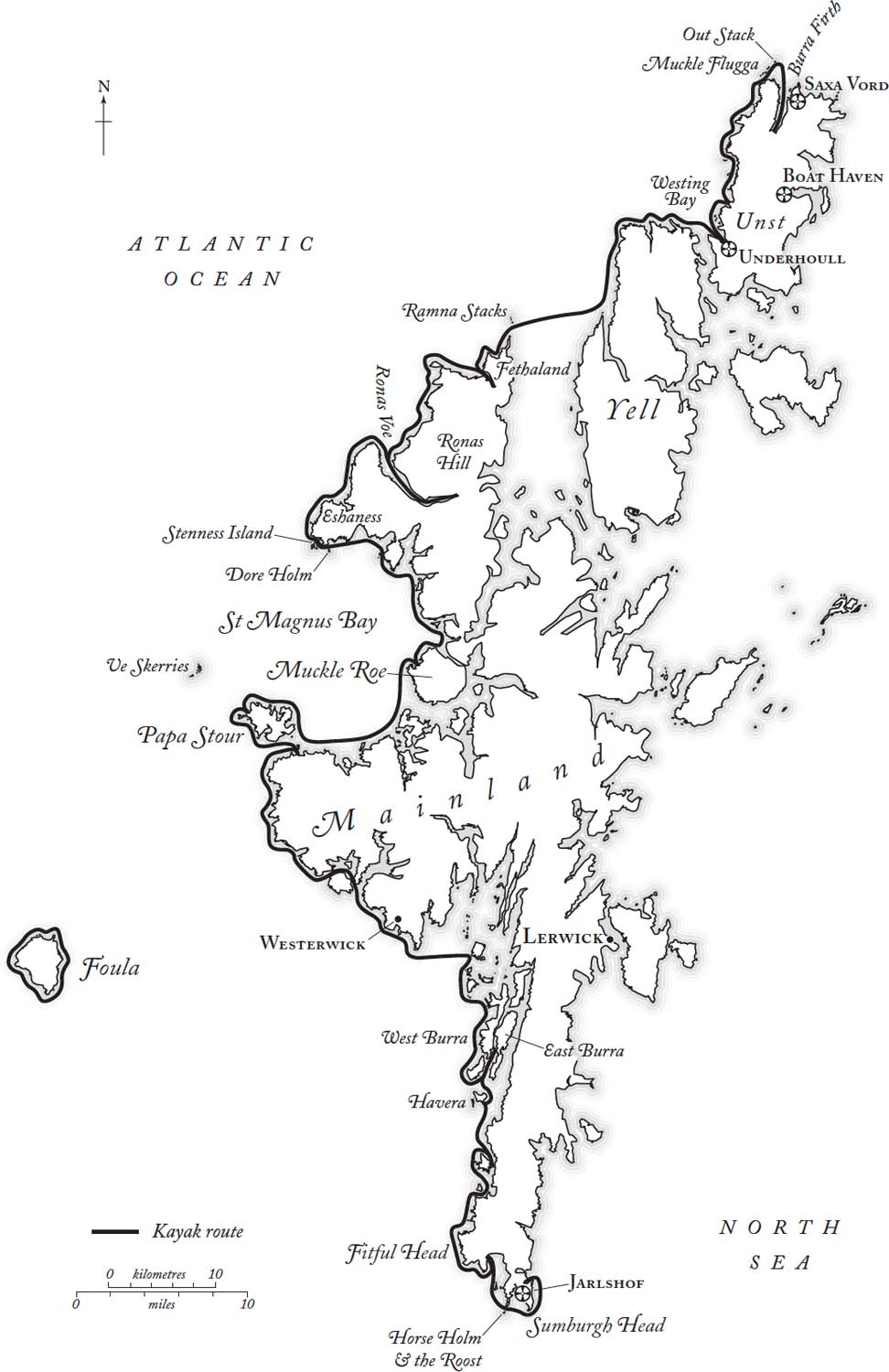

In that sense, my plan was an experiment. I hoped to see what could be learned by travelling slowly along these coastlines with an eye attuned to both the natural world and the remains of the past. The decades over which I’ve wandered here are long enough to begin to see changes and to ask what will become of these landscapes. The way in which some coastal regions were emptied of permanent populations now contrasts their growth as sites of leisure. Mountain paths grow wider and un-pathed regions fewer, coastal walking routes are extended and advertised in increasingly lavish brochures. I’d been spending nights on mountains for several years before I happened across someone doing the same, but now the experience isn’t uncommon: in the winter before this journey I even slept on a Cairngorm summit from which the only visible artificial light was the pinprick of a head torch on a distant mountain. Thanks to social media and political devolution, communities from Applecross to Anglesey pioneer new ways of living well while promoting and protecting the needs of nature. The languages of the small rural communities at the edges of the islands – particularly Welsh and Gaelic – grow in ways that once seemed impossible; lost languages like Norn have vocal advocates. ‘Small language’ networks of co-operation and exchange now link Cornwall and Wales with Breton and Galician cultures in ways that echo historic bonds along seaboards. Lynx might soon be restored to a few remote forests just as white-tailed eagles have been returned to seas and skies. Yet even the eagles are still a source of contention: beloved by tourists and naturalists they are resented, even sometimes poisoned and shot, by those who see them threaten livelihoods in farming, field sports or fishing. This book is therefore not just the story of a journey, or an exploration of past and present on the fringes of the British Isles, but a reflection on how far, and in what directions, our current interactions with the coast are reshaping this north-east Atlantic archipelago.

In attempting to tell this aspect of the story I wanted to rely on more than my own experience, so in the months leading up to my journey I made use of every professional and personal connection I had. I travelled to the University of the Highlands and Islands for events on coastal history, meeting, for the first time, the unofficial ‘historian laureate’ of Scottish coastal communities, Jim Hunter. I contacted artists and musicians, including the composer Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (an old friend of the family, who once taught me to play his Orkney-inspired music, but who passed away just weeks before my journey began). And I made use of my role as a teacher: I acquired dissertation students interested in the history and folklore of western Scotland, Wales and Ireland and wrote these places into my courses.

One class about these coasts was especially instructive. This was a seminar on ‘Film and History’ for the University of Birmingham’s MA in Modern British Studies which I taught with a historian of the twentieth century, Matt Houlbrook. We chose early films of St Kilda and the North Sea as the case studies for our students. They began by watching the first moving picture of Britain’s most famous small island: Oliver Pike’s St Kilda, Its People and Birds (1908). Then they watched four films from the 1930s, including John Ritchie’s footage of the evacuation, and Michael Powell’s The Edge of the World (1937) which was set on Kilda but filmed in Shetland. We then chose three documentaries of the eastern coastline – John Grierson’s Drifters (1929) and Granton Trawler (1934) as well as Henry Watt’s North Sea (1939) – each of which places trawlers and fishing at its heart.

The effect of putting these films side by side is striking. They show the process of these coasts being mythologised. By the early twentieth century, the North Sea had come to stand for shipping, industry and progress: its early appearances on film were commissioned by the General Post Office to advertise the vibrancy of fishing fleets and the productive potential of the ocean. Trawlermen haul herring by the thousand from the waves: despite gales and storms, these icons of modern masculinity demonstrate human dominance over nature. Film-makers experiment with advanced techniques of sound and vision as they seek to portray the striving and struggling that make a modern factory of the sea. By contrast, the west in these films signals detachment and underdevelopment. Its communities hold out against terrible odds with only vestigial industries to aid them. A lone woman sits at a spinning wheel the same as the one her grandmother’s grandmother used. A man is lowered from a cliff, draped in a sheet: he waits patiently, alone, to snag a guillemot which can then be salted for meagre winter sustenance. Children scatter, panicked by the strange sight of a camera and cameraman. Our students saw that when watching the east-coast trawlermen the viewer feels like the audience at a performance; when watching films of west-coast crofters and fisherfolk they were left with a feeling more like voyeurism.

The contrasts that appear in these films are fictions. They don’t portray these places as they exist today nor as they were when the films were made; still less do they depict a world that could have been recognised in earlier ages. Yet stereotypes like these are repeated endlessly. Twenty-first-century poets are forced to work as hard as Norman MacCaig did in 1960 to remind readers that Gaelic verse is often small and formal: grandiose romanticism and the wild red-haired Gael live in lowland imaginations, not in west-coast glens and mountains. But I can’t pretend that engrained romantic imagery doesn’t still colour my own, lowlander’s, obsession with these Atlantic fringes. Such notions are resilient to short spells on icy crags or a night in the ghostly remains of a cleared coastal township. But could they survive this journey’s long immersion in these regions? I hoped to find my imagination changed by travel: the mists of Celtic twilight dispelled perhaps, with the delicate textures of mundane and everyday history appearing from the fog. This would not, I hoped, be a tale of disenchantment, but of changed enchantment, in which the rich worlds of real human beings exceeded (as any historian will say they always do) the hazy types of myth. So I knew, when I set out, what I wanted from this journey. But if journeys always turned out how we planned, and provided answers only to the questions we knew to ask, there’d be little point in taking them at all.

Let my fingers find

flaws and fissures in the face

of cliff and crag,

allowing feet to edge

along crack and ledge

storm and spume have scarred

for centuries

across the countenance of stacks.

Let me avoid

the gaze of guillemots,

the black-white judgements

of their wings;

foul mouths of fulmars;

cut and slash of razorbills;

gibes of gulls;

and let me keep my balance till

puffins pulse around me

and the glory of gannets

surrounding me like snow-clouds

ascendant in the air

gives me pause for wonder,

grants further cause for prayer.

Donald S. Murray, ‘The Cragsman’s Prayer’ (2008)

SHETLAND

(July)

JULY IS THE TURN of Britain’s year: counterintuitively, perhaps, it’s the true peak of spring. At the month’s onset, auks and waders throng the coastline. Gulls and skuas feast on the eggs and fledglings of smaller birds, while lumbering monsters like the basking shark rise from the ocean’s depths to predate the algal bloom. In this month of frenzy, travellers by kayak can’t be sure of an onshore place to sleep, however much they scrutinise the map: when a landing is met by chittering terns the only option is to slide back onto the sea. But by July’s end, seabirds slip the leash that briefly tethered them to the land: wax becomes wane in the glut of coastal life. Winds rise, then temperatures fall, as species after species leaves, till every crag that was once a thick white fudge of feathers and excrement is flayed clean by gales.

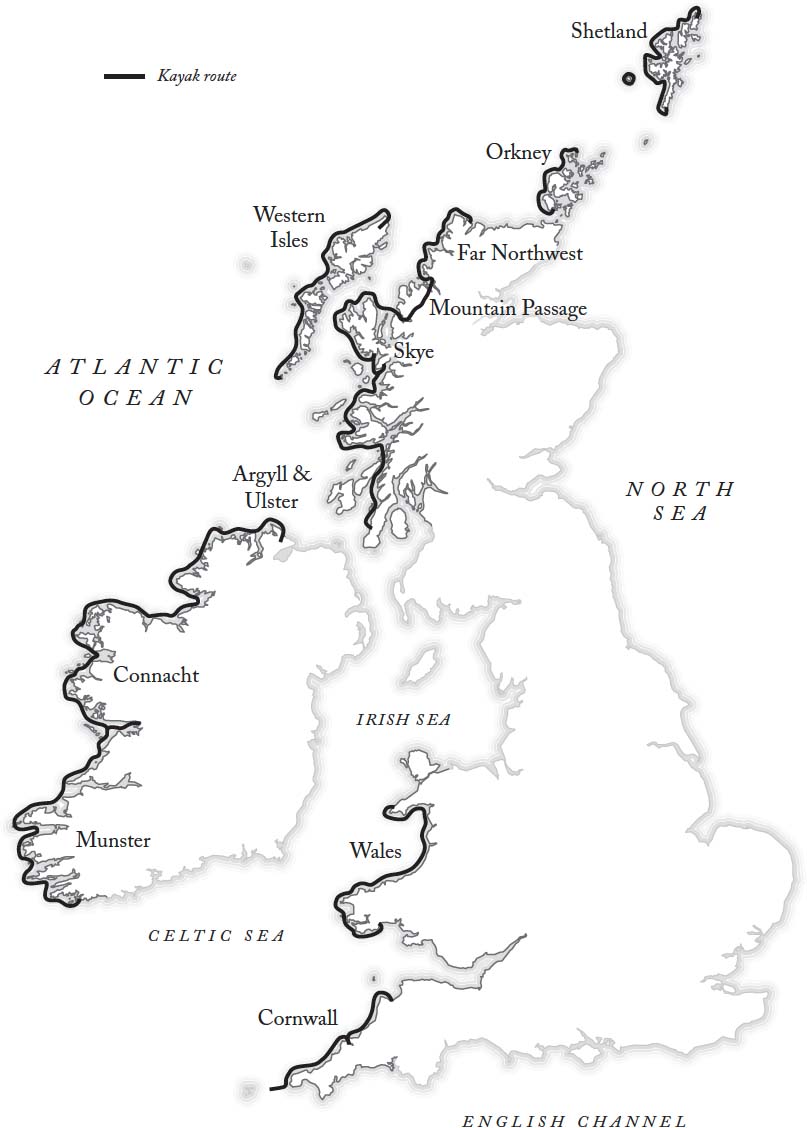

I spent my first night on Shetland high on some of Britain’s most dramatic cliffs and north of every road and home in the British Isles (figure 2.1). All night, seabirds returned to ledges below, gradually ceasing their daytime cackle; I watched the last light of a sun that barely set gleam on the backs of fulmars and puffins as they wheeled in to roost. When I woke (a mere three hours after closing my eyes) a fat skua sat feet away on the storm-stunted grass. It stared as though keeping watch, with feathers only occasionally ruffled by a hint of breeze. This morning could barely be a better one to begin my journey: in this most wind-lashed extremity of Britain all was sunshine and stillness.

Shetland felt like a fitting place to start. It embodies July’s double nature more fully than anywhere else in the British Isles. In the early summer, ‘the aald rock’, as these islands are affectionately known, is a cauldron of life as rich and distinctive as any of the world’s celebrated archipelagos, from the Galapagos to the Seychelles; its species – whether wrens, voles, moths or mosses – have evolved along unique trajectories. This month’s journey will bid farewell to the fecundity of spring with a carnival of screeching, mewling life of which this morning’s seabirds are just the start. The descent into winter in the Scottish mountains, when every plant or creature seems miraculous, will be dramatic.

Within an hour, early on the last day of June, I’ll have paddled to Out Stack: a small rock that is the northernmost scrap of Britain. I’ll turn. When I shift the sun from my right shoulder to my left, a journey that has filled my mind for months will begin. I wonder whether I should have some ritual ready: it’ll feel odd for the act that begins this venture to be a paddle stroke like all the others. But I can’t think of a ceremony that wouldn’t seem ridiculous performed, alone, at sea. So I paddle north to my starting point, passing up a long, fjord-like voe called Burra Firth. This is lined to the east with Shetland’s characteristic rich-red granite crags and stacks. To the west, a contorted, steely gneiss is shot through with quartz that, like the water, glints with silvery light. All the cliffs are swathed in a fleeting green: grass, moss and sea pinks cling to fissures in the rock through the short Shetland summer.

Reaching the mouth of Burra Firth was a decisive moment. If I turned right, around the red headland of Saxa Vord, I’d travel coasts sheltered from raw westerlies by the land mass of Britain. I’d write a book about the North Sea. But turning left is to choose the more austere Atlantic, its swell built through 2,000 miles of open ocean, and its coasts ravaged by some of the most powerful and unpredictable forces on the earth’s surface. In her unparalleled trilogy of books on seashores, the Pennsylvanian Rachel Carson makes this coast a case study precisely because of the violence of waves which sometimes break, she says, with a force of two tons per square foot.1 For now I was still shielded from swell by a long line of rocks, some with ominous names like ‘Rumblings’. These outcrops are usually known simply by the name of the largest, Muckle Flugga, which is topped by a large, precarious Victorian lighthouse. Out Stack is the last and least imposing of the group.

Only later would I learn the need to ignore names like Rumblings and Out Stack, as late impositions on the landscape. It’s a signal of Shetland’s long separateness that the islands as their people know them are named differently from how they appear on maps: Out Stack, for instance, is merely a garbling of ‘Otsta’, a name still used by Shetland fishermen. These historic names of Shetland were collected and mapped for the first time in the 1970s, and those who undertook the task referred to the lived tradition they recorded as ‘100,000 echoes of our Viking past’. Muckle Flugga is among the names that reveal the resilience of local terms most clearly: for a century, officialdom imposed the bland ‘North Unst’ on this rock, but in 1964 gave in to the Shetlandic name which – derived from the Norse for large, steep island – speaks more eloquently of geography, history and Shetland’s singularity.

Despite the shelter of the skerries, I proceeded south from Otsta with caution: as the sea spills round Britain’s apex, strong tides can change a boat’s course and sweep it into offshore waters. Just as the Atlantic breaks against these cliffs with unusual force, the tides round Shetland and Orkney are some of the most treacherous in the world. These forces, because they draw in floods of nutrients and prevent disturbance, are the skerries’ greatest asset: they permit whales to feed and seabirds to breed.

On this still day, at the height of spring, this fecundity was spectacular. It felt like a stronghold: a vision, perhaps, of how all these shores might have been before human action ravaged them. By the time I left the firth, I was no longer alone but surrounded by life, and the new entourage that whirled around me provided the sense of occasion I’d thought impossible. A moment that could have been anticlimactic became entirely magical. A long string of gannets, slowly thickening, had begun to issue from the southernmost skerry of Muckle Flugga. Within minutes, hundreds of these huge birds – with wingspans of almost two metres – formed like a cyclone overhead. They circled clockwise, from ten to a hundred feet high, tracing a circuit perhaps a quarter-mile wide, each individual moving quickly from a speck in the distance to loom overhead (figure 2.2). Moments later, dozens of great skuas (known to Shetlanders as bonxies) joined the fray, pestering the gannets (solans) and drawing the only squawks from this otherwise voiceless flock. Black guillemots (tysties) and puffins (nories) flew by too, but took no part in the larger choreography, plotting small straight lines across the expanding circle.

More perhaps than any other bird, gannets evoke the bleak world of seaweed, guano, gales, crags and mackerel that sweeps north and west of the British Isles. Spending summer in dense communities, they colonise the steepest and most isolated elements of the Atlantic edge, building a world that looks like an oddly geometrical metropolis. Their chicks are known as squabs or guga, and dozens of these black-faced balls of silver fluff were visible on Muckle Flugga as I passed. During July the guga turn slowly black and leap from their ledges into a journey south that begins with a swim: they jump before they can fly. The young birds then make vast foraging flights, gradually securing a place on the edge of a colony that might be hundreds of miles from their birthplace. Then, they’ll perch year after year in their tiny fiefdom, unmoved by everything the weather of Shetland, Faroe or Iceland can throw at them. I could feel no sense of identity with full-grown gannets, whose command of air and water transcends clumsy human seafaring; yet the guga’s hare-brained, ill-prepared flop into the sea made me imagine it as an emblem of this journey’s running jump into an alien ocean world. If I were ever to give my boat a name (and at least one Shetlander I met was taken aback, even offended, that I hadn’t) I thought an excellent choice would be Guga.

Despite the infrequency of their squawks, the noise the gannets made as they swirled above was extraordinary. The sound of millions of feathers scything the air was enough to drown the ocean. This was the first time I’d considered the importance of hearing to the kayaker: unable to listen for dangers over the sound of the gannets, such as breakers over barriers in the sea, I felt shorn of a tool critical to navigation. And the thousand shadows of these powerful creatures created just the slightest sense of threat. Indeed, besides a few seventeenth- and eighteenth-century references to their sagacity and storge (the familial fondness they show towards their offspring), humans have rarely associated gannets with anything benign. Their appearances in art and literature are shaped by their most characteristic act: the fish-skewering dive from height into the depths. Wings folded back, the angelic, cruciform bird becomes a thrusting scalpel. This is, according to the leading naturalist’s guide to the species, ‘the heavyweight of the plunge-divers of the world’ (and the gannet’s evocative power is such that even this scientific monograph can’t resist noting the bird’s ‘icy blue’ stare).2 In the 1930s, an island joke held that plans were afoot for the canning of ‘fird’ (gannets tasting like a cross of fish and bird) but that no tin could hold ‘the internal violence from the northern isle’: the gannet had come to stand for the storms of its northern outposts as well as its own oceanic stink and sudden plummet.3 And the shift from soaring beauty to abrupt violence has long been a theme to build macabre visions on; as I moved beneath the avian storm cloud I couldn’t keep the most sinister of gannet poems, Robin Robertson’s ‘The Law of the Island’, from needling its way into my head. In this beautifully distilled poem, an island outlaw is lashed to a barely floating hunk of timber, with silver mackerel tied across his eyes and mouth. The islanders who have been his judge and jury push him into the tides:

They stood then,

smoking cigarettes

and watching the sky,

waiting for a gannet

to read that flex of silver

from a hundred feet up,

close its wings

and plummet-dive.4

This captures something of the force with which these bright birds, wreathed in shining bubbles, pierce the gloomy depths. Yet real gannets are ocean survivors, not kamikaze warriors, so there was no need for empathy with the island outlaw, and never a Hitchcockian threat in this great wheeling.

In fact, the leisurely hour I spent in the sun at Muckle Flugga would be the last moment of safety for some time. As I began the journey south down the island of Unst I hit a wall of breakers and swell that beat against the most preposterous cliffs I’d ever looked up at. With astonishing precision, fulmars traced the profiles of complex waves that seemed entirely unpredictable to me. Crests soon hit the boat from both sides, forcing its narrow bow beneath pirling water until its buoyancy saw it surge up through the foam. The bow would then smack down – diving through air where there had just been wave – into a sucking surface of receding sea. Twice in the first half-hour an unforeseen peak forced me sideways and into the ocean and I had to flick my hips to roll back upright, wrenching the paddle round to twist my body out from underwater (I was desperately glad of the previous week, spent practising short journeys in surf off North Uist with the most foolhardy kayaker I’ve ever met, my partner, Llinos – figure 2.3). As the last of my gannet escort returned to their pungent white promontories, I felt my sense of distance from everyone and everything keenly. I wouldn’t see another human today, not even a silhouette on the cliffs that tower above. Even if someone was looking down, the roiling stretch of intervening ocean meant we might as well have been a world apart.

Passing down Unst was the hardest day’s travel I’d ever done. In the evening I pulled into the shelter of a small cove, Westing Bay, with the sensation that I’d walked repeatedly through a brine car wash. I set out my sleeping bag on an islet called Brough Holm which, like so many tiny Shetland skerries, has a ruin attesting to productive purpose long ago. Covered in golden lichen, the remnants of this böd (fishing store) stand among deep-yellow bird’s-foot trefoil which gives way suddenly to kelp and bladderwrack: a colourful world of greens, gold and brown that was made still richer by the evening light. The remnants of the Iron Age and Viking sites of Underhoull commanded the landward horizon, with a vantage along tomorrow’s path, which would take me across a major sea road of the Norse world: the sound that separates the island of Unst from its southern neighbour, Yell, was once the easiest route between Norway and conquest.

Safe from the sea, I shuddered at the thought of what today’s journey would have been like in less forgiving weather. I spent sunset drying out while reading about the small boats of Shetland, and thinking of centuries of families who’d rowed these coasts in all conditions.5 Far from an anticlimax, this dramatic day felt like a grand fanfare to see me on my way. Although it would be a while before I learned to sleep well in July’s perpetual light, I did doze for more than three hours that night, mostly unbothered by the outraged squeak of an oystercatcher each time a gull strayed close.

By some kind of miracle, the calm weather in which I set out held for days, with only brief early-morning interludes of cloud and breeze. I was able to travel what should have been the most challenging stage of my journey with few hardships beyond some sunburn round the ears. The two rolls in the maelstrom round north Unst were my only submarine adventures. Covering an average of thirty-two miles a day – not as the crow flies, but in and out of gorgeous inlets with imposing headlands – I still had hours to read or hang around at sea when gannets dived or porpoise fins rolled above the waves. In the orange evenings and white mornings I stretched my legs across the islands I’d chosen to sleep on and nosed round their ruins (I’ve never been anywhere with so many abandoned buildings from so many centuries). I began to think up questions for present-day islanders and for the past Shetlanders whose lives persist in the archives. But this still idyll, I had to remind myself, could not last.

The sensible way to undertake a journey along Britain’s Atlantic coast would have been from south to north. With prevailing sou’westerlies at my back I would have been working with, rather than against, the weather. But I couldn’t bring myself to do that. While planning this trip in moments snatched from university teaching, familiar English and Welsh coastlines felt like the wrong kind of start. If I was to make sense of the Atlantic coastline, I had to begin by disorienting myself with total immersion in the seascapes and histories of a place I still knew mainly through clichés of longboats, horned helmets, sea mist and gales. This place is the seam between the Atlantic and North Sea, where waves rule Britannia and always have. It is a coast of staggering diversity as well as a thriving cultural hub: those coasts and that culture are thoroughly intermixed.