The Frayed Atlantic Edge

I landed at the launch of the tiny Fair Isle ferry and crossed the narrow neck of land behind Sumburgh Head. This took me to a spot rich in historic remains, including Shetland’s most dramatic Viking tourist-draw: Jarlshof. The Norse traditions of this southern tip of Shetland are nearly as rich as those of Unst. Even the tidal stream I’d just swept through is rich in story. The Orkneyinga Saga is a tale of competition between Norwegian earls for the coasts and archipelagos of the North Atlantic; like most such sagas it is gripping and evocative but fiercely elitist, with barely a glimpse of perspectives beyond those of its entitled male protagonists. In 1148, the saga says, Earl Rognvald Kali Kolsson, ruler of the Northern Isles, was travelling between Orkney and Norway. With breakers all around, he was forced to run ashore at the south of Shetland. Rognvald wandered local settlements, enjoying anonymity and frequently (as was his habit) breaking into verse. One day, he met a poor elderly man near Sumburgh Head. Learning that the man had been let down by a rowing companion, Rognvald (disguised in a white cowl) offered to help him fish. The two rowed out to Horse Holm making for the ‘great stream of tide … and great whirling eddies’ that I’d just swept along. As the old man fished, Rognvald’s task should have been to skirt the tidal stream by rowing the boat against the eddies. Instead, he guided them deep into the turbulence where the fisherman began to draw up enormous fish, but soon cried out in terror ‘Miserable was I and unlucky when I took dee today to row, for here I must die, and my fold are at home helpless and in poverty if I am lost.’ Shouting ‘Be cheerful man!’, Rognvald rowed like a man possessed, eventually drawing them clear of the chaos and back to shore. Still incognito, he gave his share of the catch to the women and children preparing the fish on land, but then slipped on the rocks, provoking howls of mocking laughter. Rognvald muttered one of his verses, rendered here by the Orkney poet George Mackay Brown:

You chorus of Sumburgh women, home with you now.

Get back to your gutting and salting.

Less of your mockery.

Is this the way you treat a stranger?

Think, if this beachcomber

Hadn’t strayed to this shore by chance

Your dinner tables

Would be a strewment of rattling whelkshells today.

Sumburgh women, never set staff or dog or hard word

On the tramp who stands at your door

It might be an angel,

Though here, with the Sumburgh querns grinding salt out there,

It was only a man in love with the sea,

Her beauty, her rage, her bounty,

One who knows that, all masks being off,

In heaven’s eye

Earl is no different from a pool-dredging eater of winkles.

‘They knew then’, Mackay Brown writes,

that the reckless benefactor was Earl Rognvald Kolson (nephew of St Magnus), one of the rarest most radiant characters in Norse history. A fragrance and brightness linger about all Rognvald’s recorded doings and sayings, as if the long sun of northern summers had been kneaded into him.17

But da roost and Rognvald’s antics are unusual: old stories tied to Shetland landscapes are few, and documentation of Shetland’s early history is far sparser than that for other parts of Britain. From the centuries when much of the landscape would have been named we receive only the barest skeleton of events. The Orkneyinga Saga says that Shetland was split from Orkney in the 1190s after a rebellion of the ‘Island-Beardies’ (as Orcadians and Shetlanders apparently called themselves). From then on, Shetland was largely left to its own devices, although it changed hands (from Norway to Scotland) in 1469. Only when the conditions of medieval Shetland began to collapse, in the dire economic circumstances of the late sixteenth century, are there detailed written records of what life here might have been like: bitter complaints at the loss of order and well-being. By this point, Shetland was an exceptionally cosmopolitan place, the islands frequented by merchants from around Europe and the North Atlantic, so that Shetlanders often spoke some German and Dutch as well as their own Norn language.

The reason for the dearth of early Shetland stories is the eighteenth-century death of Norn. In literary terms, this loss was total: remarkably, no Norn literature survives except in second-hand fragment. Yet Shetland’s dialect tradition is a worthy successor to the Norn heritage and a key impetus behind the wealth of current literature. This is undoubtedly the richest dialect in Britain and a constant presence in the experience of visitors (few, I imagine, leave Shetland without succumbing to the temptation to call small things ‘peerie’ or to replace ‘th’s with ‘d’s and ‘t’s). It is among Shetland’s greatest assets and the source of much of the archipelago’s distinctiveness.

Once Norn died, dialect flourished. The nineteenth century has an awful reputation where dialect traditions are concerned: the bureaucratisation and centralisation of British life led many autocrats to think like Thomas Hardy’s mayor of Casterbridge, who labelled dialect words ‘terrible marks of the beast to the truly genteel’. Yet Shetland bucked the trend, forging – as always – a path all its own. By 1818, the crofters visited by Samuel Hibbert used words and grammatical constructions substantially the same as those employed by Shetlanders today (although, as the Shetland archivist Brian Smith puts it, ‘naturally, the vocabulary is different, since we live in a society where dozens of words for small-boat equipment or seaweed, are unnecessary’). But the 1880s and 90s, during which Shetland crofters and fishers were freed by national legislation from the worst exploitation of landlords, marked a particular moment of growth. The first Shetland newspapers were founded in 1872 and 1885, and both specialised in dialect prose. They ran long serials such as ‘Fireside Cracks’ (Shetland Times, 1897–1904) and ‘Mansie’s Rüd’ (Shetland News, 1897–1914) which used island language to offer subtle observations of island life. ‘My inteention’, says the narrator of ‘Mansie’s Rüd’, ‘is no sae muckle ta wraet o’ my warfare i’ dis weary world, as to gie some sma’ account o’ da deleeberat observations o’ an auld man, on men an’ things in a kind o’ general wye.’ As this suggests, these columns were not inward-looking things, but helped form distinctive island perspectives on the world at large. In this newly prolific era, Shetlanders such as Laurence Williamson began collating and categorising dialect words and phrases, while others, such as the Faroese linguist Jakob Jakobsen, began to attempt to recover the old Norn language.

In this atmosphere of renewed self-confidence, some Shetlanders, such as the dialect poet William Porteous, began to use English to evangelise the islands to those mainlanders who, if they thought of Shetland at all, pictured a dreary scene. Poetry ‘advertising’ Shetland to the urban south embraced a flamboyant romantic aesthetic that wouldn’t have been possible a century earlier. This marks, perhaps, the beginning of the idea that Shetland is the northernmost and fiercest expression of a frayed Atlantic edge worth celebrating. Ferocious storms, wind-whipped seas and bleak, unpeopled headlands could be romanticised, rather than being dismissed as incompatible with progress or politeness. In Porteous’s descriptions of the ‘strange exultant joy’ to be found in confronting ocean weather, many touchstones of later evocations of the North Atlantic sublime can be found.

Two days after completing my descent of Shetland I found Porteous’s verse in the local archives and was struck by his heroic efforts to make storms not just poetic, but an actual tourist draw. I felt that, having kayaked this far in improbably blissful calm, I still lacked a crucial aspect of the Shetland experience. But there was no need to have worried: five days after I rounded Sumburgh Head a brief but grisly weather front was forecast. I’d already decided, thanks to Sally Huband’s influence, that my last Shetland venture had to be to Foula. Given the risk of rough weather I chose not to paddle the crossing but booked my kayak onto the twice-a-week passenger ferry. At thirty feet long this is essentially just a diesel sixareen with a lid. It was perhaps surprising that only the youngest of the eight passengers was sick as, rocking and rolling, we meandered a slow course across the sea’s contours. Minutes after disembarking in Foula’s tiny harbour I launched the kayak and was paddling up the island’s east coast. By the time I reached the north-east corner, I was in a sea terrorised by breakers three times my height, from which I could look east to the whole Atlantic coast I’d paddled down. That night I wandered through the Foula coastline’s meadows of ground-nesting seabirds, taking great care to find myself a spot to sleep away from any chicks (figure 2.7).

It was on the second of my three days on the island that I finally met the force that Porteous had pronounced Shetland’s true ruler: the ‘Storm King’. That morning I’d climbed the island’s tallest cliffs and lounged, lodged among puffins, with my feet dangling 1,200 feet over the sea (figure 2.8). I sat gazing north while clouds gathered in the west and large, cold drops of water began to fall. Hundreds of screeching kittiwakes took to the air, disturbed by eddies in the wind, while spindrift skimmed the sea in all directions. The real arrival of the storm was preceded by minutes of strange, thick warmth. Then lightning flashed across the ocean, lending the swell fleeting new patterns of light and shadow, before rich, deep thunder reverberated through the rock. Puffins and fulmars joined the kittiwakes in panicked flight, and the booming cliffs themselves seemed to have come to life. The whole spectacle was as sublime and life-affirming as Porteous had, a century before, promised his urbane readers it would be:

And when the Storm King wakes from his sleep in the long, long winter night,

And, robed in his garment of silver spray, strides southward into the light –

At the sound of his voice ye shall see the waves race in for the land amain,

Then, broken and beaten on cliff and beach, fall back to the sea again.

Ye shall see the tide-race rise and rave, and rear on his thwarted path,

Till stack and skerry are ringed with the foam of the hungry ocean’s wrath.

Ye shall watch with a strange, exultant joy, the winds and waters strive,

And your hearts shall sing with the rising gale, for the joy that you are alive.18

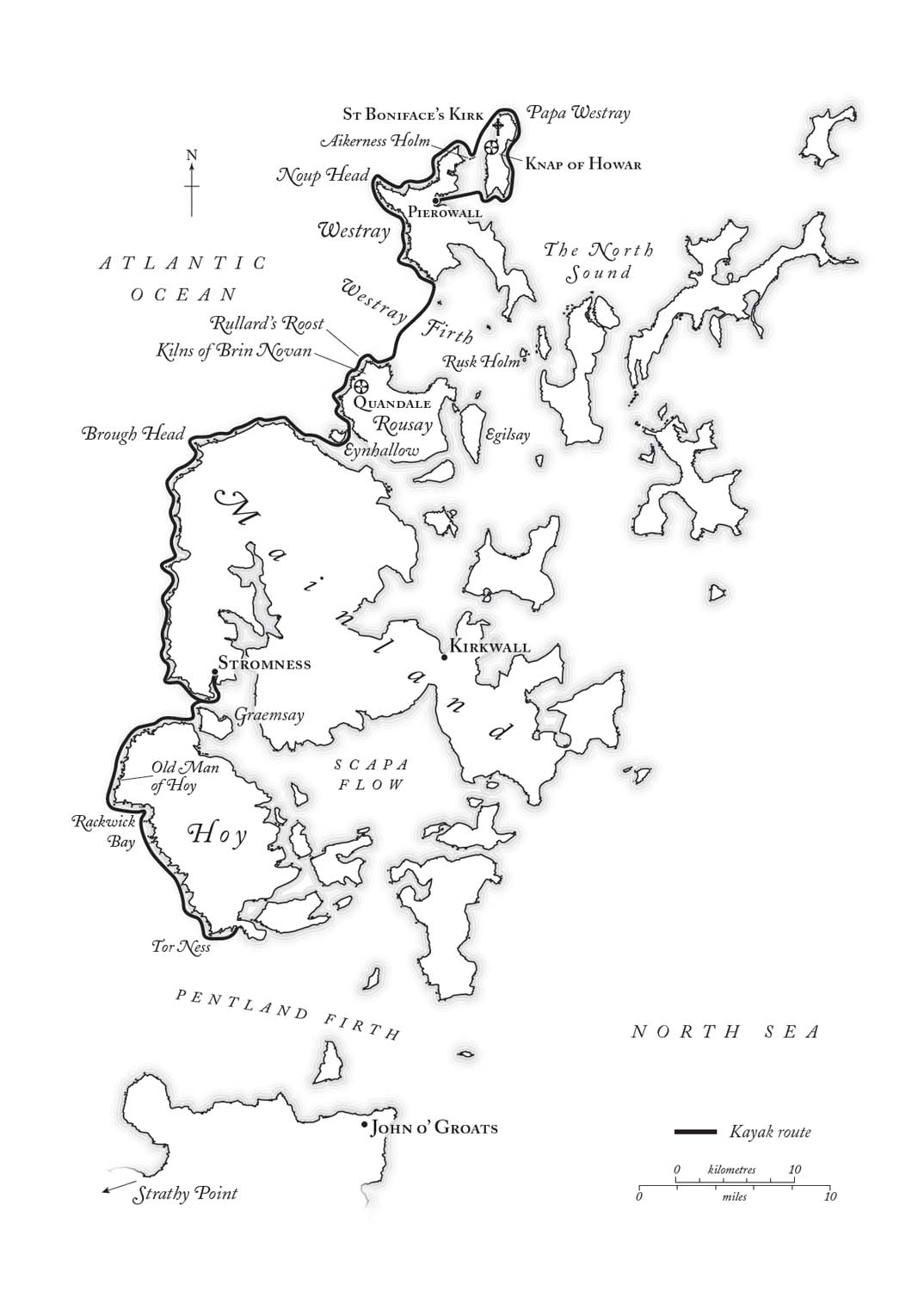

ORKNEY

(August)

Thermometer and barometer measure our seasons capriciously; the Orkney year should be seen rather as a stark drama of light and darkness.

George Mackay Brown

LATE SUMMER BRINGS uncertainty. It was mid-August by the time I resumed my journey and, in contrast to the long calm days on Shetland, the Orcadian sea changed hour by hour. Sun, squall, sea mist, rain and rainbow passed across the coastlines fast enough to make each morning feel like a time-lapsed month. When winds shifted, water responded: weather was conducted through the shell of the boat and into me, dictating the experience of each new stretch of coast. Not just perception but emotion drifted with the moods of sky and sea. This ranged from the giddy joy of lurching along, propelled by a following swell, or the anxious focus when gusts brought side-on breakers, to serenity on flat seas that seemed perfectly safe and infinitely spacious.

Phases of transition from calm to chaos were often the most sublime, binding beauty and fear together. Not for nothing are the islands of Orkney said to evoke sleeping whales: they are peaceful mounds with awful potentials. As the month progressed I saw, felt, and, for the first time, photographed, parts of waves that seemed more the habitat of surfers than paddlers. These were not the long strafing breakers that come with heavy swell (I still had some leeway before the truly wild weather of autumn); they were the standing waves that twist and coil over any obstacle to a running tide.

Atlantic waters are deceptive in changing weather. In the midst of a tidal maelstrom, hospitable seas can seem beyond the reach of imagination; yet unseen gentleness might be just a few wave crests away. This was driven home to me at the north-west corner of the island of Rousay, where the sea’s tidal features are named with the detail of a city suburb’s streets. Here, emerging from a tide race called Rullard’s Roost I hit a mesh of tide and swell so fierce that I had to head for shore: I thought my day was done within an hour of setting out. Yet five minutes later a more coastal line allowed me through: I could barely see evidence of conditions to cause concern. Much of successful kayaking is in the choice of routes between the shifting waves. As important on the water as arms or balance is a cool head through the roaring, swirling, chilling and grinding that batter the senses in a threatening sea.

Not just the weather, but also the landscapes were now defined by contrasts. On the first islands I passed, transitions from thundering cliffs to the placid undulation of cattle farms are sudden yet somehow seamless. No single landscape lasts more than a few hundred yards. On the most north-westerly island, Westray, the imposing, sixteenth-century edifice of Noltland Castle looms over a large modern farm; seen from the sea, the two occupy the same small space. Beside them, near the spot where surf meets sand, a sprawl of tyres and polythene marks a recently excavated sauna, built by the island’s Bronze Age inhabitants.

This landscape looks at once spacious and cluttered. Centuries and functions, whether sacred, industrial, defensive or recreational, are pushed together at sparsely situated sites. Around them, in wide fields that are almost moorland, the earth is loaded with low-lying detritus of millennia. When I wandered ashore, I found myself watching each inch of ground for traces of the past until every broken plastic bucket or scrap of rope became an artefact. The sounds of breakers, cattle, lapwings, tractors and voices also took on that character: items in the soundscape felt as distinctive of this place as did objects in the landscape.

After making my way north by roads and ferries I had kayaked out from Pierowall, Westray’s capital village. Its small grey buildings perch around a colourful little bay: tall yellow hawksbeard flowers and bronze kelp line an arc of golden sands and green sea. Pierowall was known to the Norse as Höfn and a row of pagan graves suggests it was a Viking-era market. When Rognvald Kali Kolsson stopped here there was a clashing of cultures: he met Irish monks whose hairstyles he mocked in verse. This pretty, ancient port was my place of departure but it wasn’t northerly enough to be my true starting point.

I began by kayaking north-east. The small island of Papa Westray, known locally as Papay, thrusts a rugged and disruptive head north of Westray and into the Atlantic’s flow. As I paddled into the mile-wide sound between islands I found myself grinning with pleasure to be back among the waves. I’d missed the ocean’s noise, the tension in the arms as they pull a paddle through water, and, most of all, the sense of unrooting that rocking over waves creates. I kayaked carelessly, enlivened by cold splashes from the bow and paddle. Yet before I’d even really got started, I felt the lure of Papay’s past.

This island proved to be the most improbable place I’ve visited. Its history emerges from waves and grasses in ways that feel surreal. Sometimes traces of the past are recent and mundane but still evocative of island life. My route reached the island at a pretty place where low cliffs are topped with a small, strangely situated structure that is blackened by burning. It stands on its isolated outcrop because this picturesque inlet faces directly into south-westerly wind and swell. For decades the vulnerability of this spot made it the ideal rubbish dump. Litter on the scale of cars and sofas would be thrown down the rocks and carried away by winter storms that were more muscular and reliable than any binmen. Local lobsters still dwell, perhaps, in the rusted boots and bonnets of Ford Cortinas.

As I rounded the island, the surprises became more venerable. I passed an enormous kelp store, a remnant of the decades round 1800 when Papay was a global centre of this major industry. Paddling past, and beneath one of the most spectacular chambered cairns in the world, I landed on a sandy beach beside a small and unassuming isthmus of stones and seaweed. I’d intended to wander up the cliffs and visit a monument to the extinction of an Atlantic seabird. But the spot I’d landed at was not what it seemed. At first, I thought I was hallucinating as I saw patterns in rocks where seaweed was strewn like tea leaves. But the more I stared, the clearer the geometry became: a cobbled platform took shape, then hints at a low stone wall. These sea-smoothed structures were centuries older than the era of kelp but, for now, the nature of their making remained a mystery.

I wandered up the cliffs to find the monument I’d stopped for. In 1813, ‘King Auk’ was the last great auk in Britain. These birds – penguin-sized relatives of the razorbill – were once prized for feathers, meat and eggs, but by the early nineteenth century the collection of stuffed birds had become a favourite pastime of Europe’s elite. What could possibly cement a wealthy collector’s status like the large, impressive corpse of ‘the rarest bird in the world’? There are many discrepancies in narrations of the events of 1813, but it seems that ‘local lads’ had killed King Auk’s mate by stoning the previous year. Now William Bullock, impresario and keeper of the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, had written to the lairds of Papay requesting the very last bird for his collection. The obliging lairds tasked six local men to row to the third cave along the north Papay crags. King Auk leapt from his perch into the sea and a marksman, Will Foulis, fired and fired again. But the auk was agile in the water. Eventually cornered, King Auk was bludgeoned to death with oars. The bloodied prize was soon in the hands of couriers to London where it became a feature of Bullock’s ever more elaborate displays, to which another one-off, Napoleon’s carriage from Waterloo, was later added.

The cairn I visited on the cliffs above King Auk’s perch was put in place by local children. Concealed in the memorial, beneath a bright red sculpture of the royal bird, is a time capsule containing the message they wrote to the future:

We wish there was still a great auk to see. We hope that people won’t have to build more cairns like this to remember things we see alive now. We humans gave a name to this bird, now only the name is left. If you who are reading this message are not human, remember us with kindness as we remember the great auk.1

The fate of King Auk marks Papay as a place of endings. But after I’d battled round the island’s violent northern headland, I reached sites that spoke instead of beginnings. The most famous is the Knap of Howar. This is the earliest known constructed house in Europe. Built as a family farm around 5700 BC the land its occupants tilled and grazed has been eaten away by water until the Knap is nestled in reach of sea spray. Its concave walls and intricate cupboard-like enclaves are missing only soft furnishings and whale-rib rafters. Rabbits burrow all round. As they dig, they disinter refuse from ancient human meals: worn oyster shells, and great-auk bones, whose flesh was stripped millennia ago. Like so many sea-lapped sites, the Knap of Howar inspires conflicting responses. Thoughts are easily lured towards ideas of timelessness, yet everything about this site has been transformed: the quality of its earth and the nature of its foliage have been slowly altered by the creeping proximity of ocean. If timelessness exists anywhere on earth, it is not in sight of the sea.

Even the Knap of Howar is not the most immediate and affecting spot here. A little to the north, St Boniface’s Kirk stands on the site of older holy places. Northerly gales flay earth from every inch of coast, changing topography by the week. Grasses and wildflowers cling to steep sandy soils where summer respite from storms provides the fleeting chance of growth before roots are ripped away and flung into autumn. It’s easy to sit and stare into the ocean without comprehending the structures of rock and shell around you. From every inch of land the ocean takes, there appears a new facet of a large medieval settlement.2 I’d glanced around layer upon layer of exposed walls and floors before I began to notice the refuse beneath them: thousands of shells of limpet, oyster and winkle clustered where they’d been littered after feasts. Storms here have disinterred whale vertebrae, from even grander feasting, and red quernstones for grinding grain, made of rock not native to the island. Remnants of the processing of pig iron and fish oil imply a community that worked the coast in sophisticated ways.

There’s something evocative about the daily changes occurring at this unmarked, uncelebrated site. The configuration of buildings and shells seen on any visit is immediately taken by the ocean, never to be witnessed again nor recorded. It’s impossible to categorise such places. Most of this island fits both poles of many binaries depending on the light you choose to see it in: human/wild, timeless/changing, productive/barren. Everything seems both out of place and perfectly positioned, and our frameworks for comprehending the coastal past feel entirely inadequate.

Unable to imagine what it must be like to live in a landscape so immediate but so inscrutable, I knew I needed help. Before setting out I’d contacted Papay’s ‘biographer’, Jim Hewitson. Jim told me he and his wife Morag intended to travel no further than the Old Pier, 500 metres from their home, for the rest of the year: when I passed, he said, I’d find them at home or in a nearby field. In the early afternoon, I knocked on the Hewitsons’ door and was led into an old schoolhouse. On one wall was a large map marked with Papay’s historic place names. Elsewhere were images from the island’s past including a painting of King Auk. This was pinned beside a memorial to a French kayaker who visited when paddling north. He’d planned his journey with his wife before her untimely death. Having undertaken the voyage alone, he disappeared, presumed drowned, before reaching Shetland; I didn’t dare ask whether he and I were the only kayakers to have visited the Hewitsons.

I sat with Morag and Jim, consuming tales of island life along with tea and croissants. Then we wandered the coast. I was soon told, in no uncertain terms, that my desire to find explanations of the coast’s mysteries was not an acceptable approach to the island. Life on Papay, they insisted, involves coming to terms with mystery, not seeing it as a problem to conquer. Jim and I revisited the strange cobbled structures of the beach I’d landed on. He told me that archaeologists call it a medieval fish farm, used by monks from a monastery that may or may not have existed when Papay might or might not have been the centre of an eighth-century bishopric founded by Iona monks (or someone else). Yet Jim and Morag’s children have found antlers in this ‘fish farm’; perhaps this was actually a spot for trapping deer whose movements would be impeded in the soft coastal ground. I was left wondering about the boundaries of ‘mystery’. Without Morag and Jim’s help it would have been impossible for me to write about the island at all. Before our conversations I had answers to bad questions; I was left with much better questions but no hope of answers. And I’d been given a reminder that archaeology is rarely about discovering or confirming facts, but more often a process of inventing the most plausible possible stories.

As we walked, pieces of Papay stone continually issued from Jim’s pockets. One contained fossilised raindrops. Another was a Neolithic hammering tool. A third had been scratched at some inestimable date with a design that echoed the hills of Westray as seen from Papay. This was Jim’s illustration of the power and persistence of island mysteries: it was probably – almost certainly – nothing, but it might be a rare piece of millennia-old representational art. I was reluctant to abandon a place with so many surfaces to scratch, and it was chastening to think I’d been tempted to kayak straight past. As a parting gift, Jim gave me an oyster shell. This was one of the many extravagantly ancient relics unearthed by the Knap of Howar’s rabbits. Or else, perhaps, the oyster was alive and well until last year, when a black-backed gull had torn it from the seabed.