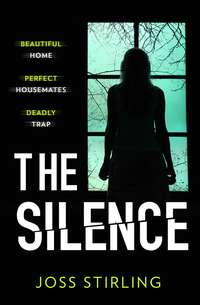

The Silence

‘If you used a voice, you could tell me what’s really going on with you. You’re always so bloody enigmatic. It doesn’t have to be robotic – not like that crap one on your tablet that makes you sound like a sat nav. I looked into it. You can get a better app than the one you use – one where you can pick accents, tone, everything, to suit you.’

He’d looked into it? Jenny supposed that was a sign that Harry still cared at some level, but his rejection had hurt. He may’ve hidden his real reason but it wouldn’t have changed the verdict. The words that she was ‘not enough’ had haunted her. She wasn’t enough for him or any man to stay with her, not even her dad.

Thank Dr Jerome Lapido for that particular neurosis, she thought with grim self-knowledge.

‘Jenny? You’ll keep in touch, won’t you?’

‘Why?’ she signed.

‘I do care, you know. We’ve been friends for nearly ten years.’ And went out for three of those. ‘You’re just a lot for a selfish guy like me to handle. Complicated. Not just the voice thing but the nightmares and such from … you know?’

Of course, she knew: it was her life that nearly ended at fourteen. She regretted she’d eventually told him the details but she’d had to as he needed to know to avoid some of her panic attack triggers. At least he appeared to have kept his word and not told the others. It would’ve been much worse to be looked on with horrified pity.

She almost typed her wish for him to have an empty, uncomplicated future of meaningless, no-strings sexual partners, but thought better of it. It would show she still carried a grudge from their break-up. You’ve got my number she wrote instead. We’ll see each other at work.

‘Yeah.’ He seemed reassured by that. ‘And good luck. Do you need any help with your stuff?’

She shook her head.

‘OK then. And sorry.’ He got up and gave her a quick kiss on the cheek. He still smelt good, the bastard. ‘Look after yourself, Jen.’

Jenny splashed out on a taxi to transport her stuff from Ebbisham Drive to Blackheath. To avoid the taxi driver striking up a conversation, she thumbed through her old messages. As friends and family knew not to call, there was plenty of these. It was hard to keep up with her mother’s continual one-sided chat. She’d turned texting into a Virginia Woolf stream of consciousness and Jenny would often find her phone had fifty or so unread message if she neglected it for a few hours. Scrolling down she came across one from a number her phone didn’t recognise. She could see the beginning of the message. Well done. You kept your promise.

What was that about? What promise? Was it a marketing technique? On any other day she would’ve ignored it, but she had time. Opening it, she read the rest of the message.

Well done. You kept your promise. I enjoyed our time together when you were 14. Want to relive the experience?

Her heart thumped against her ribcage with the first flutter of terror. So sick. She had thought these had stopped. Initially after the attack, she attracted messages from all sorts of weirdos. Her mum and the police shielded her from most, but occasionally she’d see one, or they’d find an innocuous cover and get through. They had ranged from suggestive messages, like this one where someone was pretending to be her attacker, to the seriously disturbing glitter and cutout words in cards or letters that seemed a celebration of the crime. She’d learned that there was a whole subculture of people who followed violent attacks. Her counsellor had tried to explain the pathology but even she, the professional, had struggled. As Jenny got older and seen more of life, she felt she had got to grips with some of it. People had fantasies, horrible, shocking ones, and projected them onto victims who hadn’t asked for any of this to happen to them. These sick people either liked tormenting victims or wished to be one themselves – the second seemed even worse. In Harlow, Jenny had even attracted a few so-called friends who only hung out with her because they found a vicarious thrill in being associated with her. Unsurprisingly, her trust in the goodness of people had taken a severe battering.

What to do? In the years after the incident, Jenny had had a number to forward the messages for the police to examine but she guessed that was long since defunct when the case went cold and got shuffled into the pile of unsolved. Her mum would still have a record of a current contact if one existed.

Her thumb hovered over the message, weighing up whether to upset her mother with this.

Oh fuck it. She wasn’t going down that rabbit hole again. She was so tired of being terrified. The past was the past. She was on her way to making a new start and wasn’t going to drag this into Gallant House with her. Sick caller, goodbye. She blocked the number and hit delete.

The taxi driver, unaware of the turmoil Jenny was experiencing on the back seat, couldn’t refrain from whistling appreciatively as they drew up outside Gallant House.

‘Lovely place.’

Still shivering, she nodded. With its tawny bricks, white sash windows, privet hedge and black railings it was the house equivalent of a person dressed up for a night on the town.

‘You live here?’

She smiled a ‘yes’.

‘A nanny, are you?’

She nodded. Sometimes it was just easier to agree. Her life was a confection spun of such little white lies to avoid having to admit she couldn’t speak.

‘Best of luck with that. In my experience, kids from houses like this can be spoilt little monsters. You’ll have your work cut out for you.’ He helped her pile her belongings just inside the gate. She gave him as generous tip as she could afford which probably wasn’t as much as he’d hoped. ‘Bye, love.’

She turned away as the taxi headed off across the heath to scout for fares by the exit from Greenwich Park. Taking her violin and computer bag to the front door, Jenny pulled on the bell. It literally was a bell: she’d seen it hanging in the hallway; the bell was connected to a metal rod which ran to a white knob outside, all pleasantly direct and mechanical. It took a while for Bridget to answer, long enough for Jenny to start slightly panicking that maybe she had been dreaming the offer of a room.

‘Jenny! From Kris’s message, I wasn’t expecting you for another hour. Come in, come in!’ Bridget stood by the door as Jenny ferried her belongings in from the road. ‘Do you want me to get someone to help? I’m afraid with my back I daren’t risk it.’

Jenny shook her head. There wasn’t much.

‘Just leave it in the hall for now and come and meet my guests. I didn’t tell you about my Tuesday gatherings, did I?’ Jenny shook her head, wondering what excuse she could conjure to avoid being dragged before a crowd of strangers. It was always so humiliating for her and frustrating for them. ‘You’re welcome to bring friends. It’s such a lovely evening, we’re in the garden. Keep your jacket on. There’s a definite nip in the air.’ She didn’t wait for an answer but assumed Jenny was following her down the stairs to the basement, out of the dark passageway and into the brightness of the garden.

Run upstairs, or follow? There wasn’t really a choice, was there?

Bridget’s guests were having drinks under the huge lilac tree that dominated the upper lawn nearest the house. It was a patchy, twisted thing, dead branches mingled with those bearing blossom, attesting to its great age. The flowers were white, their scent quite overwhelming. Dark butterfly shadows fluttered to rest on hair and shoulders of those below every time the lilac tossed its branches in the evening breeze. Jenny blinked, trying to clear her sight of the sun-dazzle on cut-glass tumblers.

‘Pimms? Or is it too early in the year for you?’ asked Bridget, going to the table.

Jenny gave a thumbs up. Doing this with a cushion of alcohol was preferable.

Bridget handed her a tumbler filled with pale red liquid and floating fruit and mint leaves. ‘I’m glad you’re like me and never think it’s too early for Pimms. Now Jonah here swears he won’t touch the stuff. He says he’s strictly teetotal. Jonah, this is our new house guest, Jenny.’

One of the three men at the table got up and came to her. He wasn’t how Jenny had imagined. In fact, she assumed the other youngish man was Jonah, as he looked more the part. As an aspiring actor, she’d predicted her housemate would have the classic good-looking Brit appearance, the floppy hair of Sam Claflin, the smouldering gaze of a Kit Harington. Instead he was crewcut, and decidedly edgy in appearance, skin in poor condition, blue eyes flicking from her to Bridget in a sure sign of nerves. Crudely drawn tattoos webbed the backs of his hands. He had two bolts tattooed either side on his neck.

‘Hi, Jenny. Mrs Whittingham warned us that you didn’t talk.’ His voice was much the most attractive things about him: a little bit London, but deep and resonant. It was a surprise coming from his strung-out frame, a bit like George Ezra’s bass-baritone emerging from such a lean person.

She smiled – her equivalent of ‘hello’.

‘And these are our friends,’ said Bridget, turning to the rest of the group. ‘Rose, meet Jenny. Rose has known me for ages, haven’t you, dear?’

The thirty-something woman laughed. She was small, and had an elfin haircut framing a heart-shaped face; Jenny got the impression of someone packed with energy. ‘If you call ten years ages, Bridget. I was one of Bridget’s tenants once upon a time, Jenny, when I thought I might make it as an actress. That’s until life disillusioned me. I went into psychology instead.’

‘And this is Jonah’s friend, William Riley.’

A bearded man, hipster to the core, whom she’d wrongly guessed was an actor, got up and offered his hand. ‘Call me Billy. I’m not supposed to be here you know. I just came to check up on Jonah and got inveigled into drinks.’

Jenny shook his hand.

‘And last but by no means least is darling Norman.’ Bridget placed her hand lightly on the shoulder of a rotund man with a balding pate. He was dressed in a tweed suit with a mustard yellow waistcoat straining across his middle. ‘Norman’s our neighbour and local historian. He also manages to fit in being our GP. A man of many talents.’

‘Bridget, you are a terrible flatterer! I’m no historian – I merely dabble. Bridget is compiling a history of this house and I’m helping her with some of the context. She’s got into the bad habit of overstating my qualifications.’ His exuberant white eyebrows arched over dark eyes.

‘Give Jenny one of your cards, Norman, so she knows where to register with a practice.’ Bridget patted the seat of a spare garden chair. ‘Now sit down, dear. No one is going to grill you so you can relax and enjoy this lovely evening. I do believe it’s the first time I’ve been able to have my drinks outside this year.’ Bridget deftly turned the conversation to Jonah’s latest role. Jenny noticed how everyone present took what seemed like familial pride in his achievements: Rose was beaming like she was his big sister at prize giving; Billy regarded him like an approving brother as Jonah described his latest episode attending an accident in a prison; Norman guffawed like everyone’s favourite uncle at Jonah’s navigation mistake that saw the ambulance turn into a real A&E bay, rather than the fake one the crew had constructed; and Bridget presided over the let’s-love-Jonah Fest with a matriarchal poise. No one made clumsy attempts to include Jenny or make her communicate. Her fear that she would be humiliated subsided.

Would she be here long enough to have this sense of family pride extended to her? Jenny wondered. Her mother was her main cheerleader but Jenny no longer lived at home to have her minor triumphs praised on a daily basis. It might be nice to be included.

There was a lull in the conversation as Bridget went in to fetch some nibbles to go with more drinks.

Jonah rubbed his hands. ‘Thank God she’s setting out the grub. I’m starving. Bridget’s Tuesday nibbles are spectacular, much better than a bag of crisps or bowl of peanuts. You’re a violinist?’

Jenny nodded. She couldn’t keep her participation limited to nods and shakes of the head. They’d given her enough time to feel the ice was broken. How long have you been acting? she wrote.

‘Not long. A year maybe. I’m in drama school but they let me have time off when I get a job.’ She wondered how old he was as he looked at least her age, rather mature for drama school. ‘It’s what we’re all there for after all. I have Dr Wade to thank for that: she helped me get in and find an agent.’

Rose waved that away. ‘It was your own talent that did it, Jonah. I’m pleased you’ve graduated to ambulance driver and got away from all those gang member roles.’

Jonah rubbed at his spiderweb on one knuckle. His hands looked raw, like he suffered from eczema. ‘Yeah, but my character has a drug problem and I’m stealing from the hospital pharmacy. I’m not sure I’m going to survive beyond the season finale.’

That explained the edgy look. Perhaps he was a young guy who just had the misfortune to look older, like those men who go bald prematurely? He had all his hair but his face wasn’t the smooth one of the newly hatched student. Lines bisected the top of his nose and dug in round his mouth.

‘You might,’ said Billy in a bolstering tone. ‘And eight weeks of steady work looks good on the CV. More jobs will come your way, I’m sure.’

‘It does look good, but my tutors tell me I have a problem.’ Jonah cracked his knuckles, not noticing the number of winces around the table. ‘If I change my looks, I don’t get these parts; and if I get these parts, I can’t change my looks. They think I might get boxed in.’

Jenny was pleased to hear that the ‘just got out of prison’ vibe he projected was for show. She wouldn’t like to be sharing a house with someone who might be a threat to her.

‘Maybe you should just look the way you want to look and leave the rest to hair and makeup?’ Thus spoke the psychologist.

Jonah scratched at his close-shaved head. ‘Maybe I’ll risk it. I’d like to grow this a little longer. People don’t sit next to me on public transport.’

‘Keep it, m’boy. You don’t want people sitting next to you. Each of them is a disease vector.’ The GP rattled the ice in his gin and tonic. ‘Can’t wait to retire and get away from the lot of you!’ But he said it with a smile to soften the words.

A bell rang inside – not the front door but another one with a higher tone.

Jonah leaped up. ‘That’s my summons.’ He dashed inside.

‘Very Pavlovian of Bridget,’ said Norman. ‘She always gets her houseguests very well trained by the time she’s finished. That boy was the epitome of rudeness when he first moved in and now look at him.’

‘She shames us all into manners,’ agreed Rose. ‘Not that she’s going to have any trouble with this one, I can tell.’ She smiled warmly at Jenny. ‘You’ve fallen on your feet here. When I couldn’t get a breakthrough as an actor, it was Bridget who gently nudged me from dead-end jobs towards doing something with my psychology degree. I think I’ve learned some of my best tricks with patients from her.’

Jenny drew a question mark in the air.

‘Things like how to put them at ease when they come into my office for the first time, how to draw the best from them. Jonah’s a case in point: a more lost young man I’d never met and now look at him.’ She stopped. ‘Sorry, that was very unprofessional. Forget I said that.’

‘It’s tempting to talk shop. We get it, Rose,’ said Billy. ‘I have to remember not to take my work home with me.’

What do you do? asked Jenny.

‘I work for the probation service. I find it very rewarding, especially on a day like today.’ He toasted her with his Pimms.

Jenny couldn’t quite see the connection but replied with a raised glass as expected.

Bridget and Jonah returned with trays of food – little asparagus quiches, salmon blinis, Parma ham wrapped around mozzarella balls, and tiny chocolate brownies. Jenny could now understand why these gatherings were so popular. Everything tasted as good as it looked.

‘Tell me, Bridget, that you got these at Waitrose,’ said Rose after eating her fill. ‘You make me feel so inadequate.’

Bridget collected in the empty side plates. ‘You know I like cooking. Anyway, these are simple to make. I could show you.’

‘I might take you up on that, but not tonight. I’ve got some work to do. Goodnight everyone. Billy, can I give you a lift to the station?’

‘Thanks, Rose.’ After a quick round of farewells, they left together.

‘And I must be off too. Got the grandson of an old friend coming to stay till he can find his own place. Better move some of my books off the spare bed.’ Norman hefted himself to his feet. ‘Here’s a card, Jenny. Don’t forget to register. You don’t have to sign on my list as they’re putting me out to grass soon. I’ve plenty of youngsters as my partners, including a female colleague or two.’ He winked and then waved farewell to the others. He headed home, not through the house but through a gate in the wall that opened into his garden.

‘I found Norman using the downstairs bathroom this morning. Red faces all round,’ said Jonah when the GP had gone.

‘His boiler’s out. I told him to come and go. We keep an eye on each other’s house,’ said Bridget. ‘We don’t stand on ceremony.’

‘I was just warning Jenny. I found it difficult to meet his gaze tonight after the eyeful I got this morning. He appears to think a towel enough covering to walk between his house and yours, and I’m afraid to say it doesn’t quite hide everything it should.’

Jenny made a note to be careful when venturing downstairs in the morning in case she met the streaker doctor.

Bridget stacked the empty tumblers on the drinks tray. ‘Don’t tease, Jonah. Norman is a perfectly respectable man; he just has a boiler problem.’

‘He has a buttock problem,’ muttered Jonah.

‘I didn’t think the young were so prudish. Jenny, what do you think?’

There was nothing Jenny could write down that wouldn’t sound completely wrong.

‘Mrs Whittingham, what do you expect her to say? That she’s fine with nudity?’

They picked up the trays and carried them towards the house.

‘We’re all human.’

‘But not everyone wants to be reminded of that in the shape of a dotty seventy-year-old man. You have to protect my delicate sensibilities, Mrs Whittingham.’

‘You – sensitive!’ Continuing to bicker good-naturedly, they went into the house, Jenny trailing after them. This house was proving even more interesting than she thought.

Chapter 6

Jonah, Present Day

They’d had a break during which Jonah had decided to keep lawyers out of it for the moment. He knew how to talk without saying anything.

‘Tell us how you feel about the women you shared the house with.’

Jonah was struck by the inspector’s use of past tense. ‘I’m not going back there?’ The sergeant was looking at him as if he disappointed her, like there was something obvious he was missing.

‘Do you think that would be appropriate under these circumstances?’ said the inspector.

Had he lost the right to walk those corridors, rooms and gardens of Gallant House just because he’d lost his temper the once?

But you hurt her, Jonah, said a snide inner voice.

He could no longer remember clearly what he’d done, just that he’d been driven to it. Not his fault.

So for that, he’d been kicked out of paradise. An overwhelming feeling of relief swept through him.

Chapter 7

Jenny, One Year Ago

Jenny hauled her bags and boxes up to her room one by one. There was no sign of Jonah when she would’ve welcomed the help. Maybe he only carried things in exchange for food? She didn’t even know which room he was in to knock on the door. Never mind: she was used to doing things alone. Hadn’t she decided she preferred it that way?

Belongings safely ferried, she stood for a moment to take stock of her new kingdom. It was clean and neat – just as she liked, no, needed it to be. The light was fading but the view out front was unsullied by streetlights. A bold orange tinge flushed the horizon, indicating the busy heart of London just over the hill, but here it could almost still be the eighteenth century when the house was built. That’s if you ignored the cars and the planes winking by, lining up with the Thames to land at Heathrow.

Pulling her duvet out of a box, she went to the bed to strip off the white lace counterpane. A bouquet of orange Californian poppies lay on the pillow. Petals fell off as she lifted it. Someone should tell the cleaner that poppies made terrible cut flowers. All she was left with was confetti and unattractive stubby heads on hairy stalks. She placed them in the bin, reminding herself to get rid of them before the next visit by the cleaner so as not to offend her.

Odd though. Bridget hadn’t mentioned anything about a cleaner in her briefing on house rules. Jenny didn’t expect one but she should make it a priority to ask. She liked to know if someone was coming into her space so she could prepare.

It didn’t take long to unpack. Her books went neatly onto a shelf by the fireplace, Maya Angelou, Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche, Jane Austen and Vikram Seth all snuggled together. Growing up, she’d craved culture of all sorts – theatre, literature, but mostly music. She’d been teased for it as a child as other kids didn’t get it; now she found there were far more of her tribe out there than she expected, people like Louis. That was the best thing about adulthood: not having to apologise for your taste. Next was her mini speaker and docking station. She thumbed on Stravinsky’s Petrushka on her phone as she had to play that piece the following day. Shaking out her clothes, which were heavy on the black skirts and shirts, light on anything pastel, she hung them in the white wardrobe. That amused her: it was shaped like the one that danced in the The Beauty and the Beast film. She waltzed a few steps with one of her long dresses and laughed, before putting it away. Underwear hid itself in the top drawer of the dresser – it didn’t look fine enough for this place. Perhaps she’d buy herself some silky lingerie with her savings? Could she even consider dating again? Harry’s rejection had scared her off men for months. She’d foolishly thought he was the one, her childhood sweetheart. Her mum had warned her not to fall for her own fantasies about the relationship. Nikki Groves had done that with Jenny’s father and ended up a single mum in Harlow.

Mum would love it here.

And now the bathroom. Jenny swept into it in manner gently mocking of Bridget’s prima ballerina style. She emptied her toiletries into the vanity unit, leaving out on the ledge her favourite perfume, a tub of moisturiser and her seven-day pill dispenser. The plastic compartmented box looked ugly compared to everything else. She’d have to see if she could find an antique one on one of the junkeroo stalls in Greenwich market. She ran the tap. With a few groans and splutters it eventually ran warm, then scorching hot. Nothing wrong with Bridget’s boiler. She added some cold and washed her face thoroughly, removing all trace of makeup. She was going to be happy here, she could just tell.

Dabbing her face dry, she went back into her bedroom, clicked off the music and took her violin out of its case to tune it. A little thrill ran through her. Though she held the instrument for hours each day, she still got that shiver of anticipation, like the wonder of first love, when she knew what they were about to do together. An ocean of classical music gently lapped before her mind’s eye: everything from the storms of Beethoven to the silences of Arvo Pärt. The violin brought it all within her reach. They would have to wait though because she really needed to practice for tomorrow. Would that disturb anyone? It was bound to annoy Bridget and Jonah if they were having an early night. The snug? Was that far enough away from the bedrooms? Taking her music and folding stand in one hand, the violin and bow in the other, she went downstairs and set up the score for the concert. Her fingering for the opening scene still wasn’t right. She loved the Russian folk tunes that weaved in and out of the composition but she hadn’t quite captured the spirit of them. Violin loose at her side, she closed her eyes for moment and breathed to ease the tension in her back muscles. She tried to summon up her impressions of Tsarist Russia: bright peasant clothes, long winters, furs, puppet shows, dancing bears, sleigh rides. Ready now, she set the violin in its notch under her chin, ignoring the familiar twinge of pain, and launched into the first song. Yes! That felt good. The high ceiling flattered the sound of her violin solo. It was so much better practising here than in her old house. Reaching the end without a mistake, she held the last note.