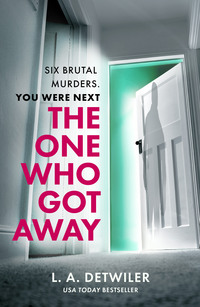

The One Who Got Away

The One Who Got Away

L.A. DETWILER

One More Chapter

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2020

Copyright © L.A. Detwiler 2020

Cover design by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Cover images © Shutterstock.com

L.A. Detwiler asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008324667

Ebook Edition © February 2020 ISBN: 9780008324650

Version: 2020-01-31

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

To my grandfather, Paul J. Frederick

‘I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity’

– Edgar Allan Poe

Prologue

West Green, Crawley, West Sussex, UK

Smith Creek Manor Nursing Home

2019

Clutching the chilled silver edges of the picture frame, my shaking hands rattle the loose glass shards that rest on the photograph. The peeling wallpaper of my room is marked with a mystic yet clear warning. I smooth my thumb over the ridges of the familiar texture on the frame, looking down at the unassuming, smiling faces in the photograph. They had no idea that years later, they’d be pawns in this sick and twisted game. How could they, after all?

Claire brought me the photograph only a couple of days ago to replace the last one. Has it really only been a couple of days? So much has changed. I can’t even keep track of the days, the hours, the minutes. Tears splash onto the glass shards, swirling in small, delicate puddles over our faces. I can feel my heart constricting, tightening, and I wonder if this is where it all ends.

‘Charles, what is this? What is this?’ I whisper into the room, my breathing laboured as the glow from my lamp dances over the message on the faded, sickly wallpaper. I shake my head, trying to work out what to do. I could push the call button over and over until one of them comes. I could wait for a nurse to get here. They would have to believe this, wouldn’t they? They would have to see that I’m not mad, that this is real. They wouldn’t be able to feed me lines about my warped perceptions of reality or this disease that is degrading my mind.

They’d have to see it.

Then again, who knows anymore. No one seems to believe me at all. Sometimes I don’t even know if I can believe myself. I stand from my bed, setting the crushed picture frame down and leaning heavily on the tiny wooden bedside table. I pull my hand back, looking down to see blood dripping from where a piece of glass has sliced into me. The burning sensation as the redness cascades down my flesh makes my stomach churn.

What’s happening to me?

I need to solve this, but I know I’m running out of precious time. He’s made it clear through the message on the wallpaper that this is all coming to a devastating conclusion – and soon. I don’t know when this story will end or exactly how. But this tower is ready to topple, crashing down and obliterating me in the process. I can’t let that happen without uncovering the truth. I can’t leave this place as the raving lunatic they all think I am. I have to stay strong and sort this out. Charles would want me to uncover this debauchery. They all need me to work this out, even if they don’t realise it.

And most of all, I need to die satisfied that all has been set right, that injustices have been paid for. I can’t leave this world with all the murky questions swirling in my mind, and with all the old guilts rattling about. Someone needs to pay for the sins of the past – and I don’t think it should just be me.

I take a step towards the wall, my bones aching with the effort. I am careful not to slip, a few loose shards and specks of blood dancing on the floor in intoxicating patterns. I focus my gaze back on the words that taunt me.

I lean my forehead against the wall, not caring that the oozing liquid will be in my hair, on my face. I inhale the rusty scent of the dripping note in the corner of the room.

You’re mine.

It trickles down, the blood an oddly blackish hue on the tired wallpaper of Room 316. I lift a trembling hand to the phrase, my finger hesitantly touching the ‘Y’. Its tackiness makes me shudder. It’s real. I’m not imagining it. I’m certain that it’s all real. Taking a step back again, I slink down onto my bed, my cut hand throbbing with pain as I apply pressure to it. My fingers automatically pick at the fluff balls on the scratchy blanket. I should probably push the call button. I should get help, get bandaged. I can’t force myself to move, though. I tremble and cry, leaning back against my bed.

I don’t understand. There’s so much I don’t understand.

I rock myself gently, my back quietly thudding against the headboard. I think about all the horrors I’ve endured here and about how no one believes me. Like so many others, I’m stuck in an unfamiliar place without an escape. Unlike Alice, my wonderland is a nightmarish hell, a swirling phantasm of both mysticism and reality – and there are no friendly faces left at all to help me find my way home.

The babbling resident down the hall warned me. She did. On my first night here, she told me I wouldn’t make it out alive. Now, her words are settling in with a certainty that chills my core. True, it wasn’t the most revolutionary prophecy. No one comes to a nursing home expecting to get out alive, not really. Most of us realise that this place is a one-way ticket, a final stop. It’s why they are so depressing, after all. It’s why our children, our grandchildren, our friends are all suddenly busy when the prospect of visiting comes up in conversation. No one wants to come to this death chamber. No one wants to look reality in the face; the harsh, sickening reality of ageing, of decaying, of fading away.

Still, staring at the warning scrawled in blood on my wall, I know that maybe the woman down the hall meant something very different with her words. I’m going to die here, but not in the peaceful way most people imagine. I’m going to pay first. I’m going to suffer.

But why me? And why now, after so many years have passed since those horrific incidents of my past?

I don’t know who to trust anymore. I don’t know if I can trust myself. My mind is troubled, and my bones are weary. Maybe the nurses are right. It’s all nothing more than this disease gnawing away at me.

But as I look one more time at the blood trickling on the wall, I shake my head. No. I’m not that far gone. I may be old, frail, and incapable of surviving on my own, but I haven’t gone mad yet. I know what’s real and what’s not. And I’m certain this is demonically, insidiously real. Someone here wants to make me pay. Someone here has made it their mission to torment me, to toy with me. Someone here at the Smith Creek Manor Nursing Home wants to kill me. In fact, someone here has killed already.

My hands still shaking, I appreciate the truth no one else can see – it’s just a matter of time until they do it again.

I lie back on the bed, the pieces of glass and the blood cradling me. Maybe, in truth, I resign myself to the fact that I’m helpless, that I’m at a mysterious Mad Hatter’s mercy in this ghoulish game of roulette. I stare at the ceiling, the hairline crack beckoning my eyes to follow it. I lie for a long time, wondering what will happen next, debating what new torture awaits, and trying to predict what the final checkmate will be in this sickly game.

After all, no one gets out of here alive. Even the walls know that.

Chapter 1

Smith Creek Manor Nursing Home

2019: One month earlier

The first thing I notice as I’m led into Smith Creek Manor Nursing Home is that the creeping ivy vines strangle the windows. Up, up, up, the vines twist and turn, suffocating the glass panes, choking out any hope of the sun shining into the unsettling, old building. They are a prominent scar on the stone front of the building, marking it as forgotten and dilapidated. It’s a violent disparity with the clean, modern look in the pamphlets they gave to us months ago.

‘Charming, isn’t it?’ Claire beams as she squeezes my arm too tightly, leading me through the creaking front door of the majestic yet decaying building. As I cross the threshold into the draughty building, reality settles in.

There’s no turning back. I live here now. People will walk by on their way to work or to restaurants or the shops, oblivious to me. They won’t think about me or the others here as they try to shield themselves from the stone presence that is a blatant reminder of their own fate. I’ll be the one no one’s thinking about, abandoned in a place called home but feeling like nothing of the sort. The familiar, terrifying twinge in my chest aches, and I clutch at my heart. I squeeze my eyes shut, pausing inside the building as I gasp for air. It hurts to breathe, and the panic doesn’t help. As my heart constricts, the familiar fear usurps me – this time, it will be too much to take. This time, the throbbing won’t stop, and it will all end here, right now.

‘Mum, are you all right?’ Claire asks, patting my shoulder with a concern a mother should express for her child, not the other way around. The order of things is so warped during the ageing process. It takes a moment for me to respond. I try to catch my breath, leaning on the wall, my fingers resting on the scratchy, chilled stone. It’s happening again. Why does this always happen?

After a long moment where I wonder if my lungs are going to keep working, the feeling passes. I open my eyes to look at my daughter, her face contorted with fear. This is why I’m here. This is what put me here, I know. I probably do need to be here, but that doesn’t make it any easier.

I take another deep breath, nodding at my daughter in assurance. She stares for a moment, probably deciding what to do. But I’m here now, and this is the best place for me – or so everyone says. Thus, she leads me forward, and we methodically trudge further and further into the cave that is Smith Creek Manor. Claire bubbles on about how lovely the statue is inside the door and how bright and airy the entrance is. I nod silently, knowing why she’s raving about architectural features. She wants this to work out. No – correction – she needs this to work out. As a fifty-two-year-old divorcee, she’s got more pressing matters to worry about than her daft old mother who is incapable of living on her own. She needs to get back to her job, the life she’s created for herself here in Crawley. She wants me to be happy here to quell her rising guilt. I understand. I don’t blame her. But it doesn’t mean I find Smith Creek Manor charming or likeable or anything of the sort. I don’t want to be here, even if my thudding chest and exhausted mind tell me I probably need to be.

It’s true, I’m being unfair. Any place but 14 Quail Avenue would be a disappointment to me right now. I miss my familiar house in Harlow. I miss Charles. I miss my marriage, my life and the place I called home for so long. This isn’t home. Crawley hasn’t been home for decades, not for me at least. I suppose in many ways, even all those years ago when I lived here during my teenage years, it never was home. In fact, for many years, it was a dark stain in my life, a reminder of all that can go wrong in the world. And for so many years, I’ve thought all of this was in my past – buried deep, deep in the past.

I know it’s pointless to get nostalgic or angry. It’s all done. It’s over now. The for sale sign in front of our house in Harlow was changed to sold. My few belongings were packed, the finances and paperwork were taken care of. I’m here. There’s no turning back.

It pains me to think about 14 Quail Avenue having new tenants. I hate the thought of some new couple dancing underneath the kitchen arch where Charles used to kiss me on the cheek before leaving for work. I loathe the thought of some frilly woman redoing the wallpaper that I loved so much in the sitting room or modernising the charming fireplace that Charles built by hand. Pain throbs in my chest at the thought of the new couple’s children or grandchildren playing with toy cars and dolls in the spot of the sitting room where my dear Charles fell over, dead, one year ago. I hate them. I hate this place. I hate it all.

‘Ms Evans, welcome. So lovely to see you. Welcome to Smith Creek Manor. What a lovely choice for your new home,’ a woman in shiny way-too-high heels offers. She shakes Claire’s hand before rubbing my shoulder. Thus, the patronising gestures begin. I shrug it off. I know I’m just sensitive today.

‘Now, let me show you to your residence. You’re so lucky, a third-floor room. You’ve got one of the best views here,’ the chipper woman announces as her bone-coloured shoes clack on the floor, her feet landing close together with each step as her hips sway with confidence. She acts as if she’s on a fashion runway instead of in a cold, damp corridor in a home for the dying that reeks of medicine and hospital. She leads us down the corridor and through a doorway that has a code on it. Above the code box is a bright coloured painting. It’s as if they’re trying to disguise the fact that this is only one step above incarceration.

Claire and the lady – has she told me her name? I’ve forgotten – chatter on about meal timetables and activities and all sorts of things, both trying to convince themselves that this is a perfectly acceptable arrangement and that I’m not coming here to die. Once inside the locked door, we wait for the lift to take me to my new view. I peruse the open area. The smell of this place matches the depressing sights. All around, people in various states of decay clutter the common room, some sitting stooped over in chairs, some sleeping. A few traipse about, dragging their feet on the carpet and muttering incoherently. Only a handful look conscious, reading a book or staring at a telly that looks like the first set Charles ever bought for our house.

The word death floats above these people, tainting the air with a musk of disintegration mixed with rubbing alcohol. That smell. How does one describe it? A sterile crispness infiltrated with what one would suppose melancholy smells like if it had a describable stench. It assaults my nose as the lift dings and the doors drag open, the fluorescent lights blinding me as I creep into the metal box. The doors screech closed, a grating noise that makes me anxious. I can’t help but feel like I’ve been enshrouded in my funeral clothes as the doors shut and we float up, up, up, the lift clunking and sputtering like a death trap. My heart pounds as I lean on the wall, my armpits getting profusely sweaty at the claustrophobic feeling. The lift grinds and creaks, and I may be imagining it, but it feels wobbly.

The ride seems to take forever, and, at a point, I wonder if it’s broken. When it slams to a stop, the doors take an interminable amount of time to creak open. Finally I see the bright lights of the corridor and I’m thankful, shoving my way out to escape the metal box of death. If I never have to get in the thing again, it would be too soon.

‘The lift’s just a bit slow. But I think it’s a good thing,’ the tour-guide woman announces as she and Claire follow me out.

I don’t understand how anything about the lift is a good thing. It’s just another reminder that this place isn’t anything like we thought it would be. My heart races as I consider the possibility of riding in that box again, the slowness of its heavenly ascent jarring.

My heartbeat steadies, and I take a few breaths. It wouldn’t do to let the lift ride get me worked up. After all, the doctor is always chattering incessantly about my heart troubles, palpitations, and stroke risks. He’s always trying to help us prepare for what to expect with the dementia as well. He reassures me with the promise of lucid days and moments amidst the days of confusion, as if that’s a true comfort to the soul to know that even though my mind is failing, there will be moments everything is clear.

Sometimes, I’m convinced he just likes to use medical jargon to sound important. Sometimes, though, I think maybe I’m actually falling apart, especially on days when the familiar pain resurfaces and I can’t catch my breath. Regardless, his warnings worked because eventually, it convinced Claire that living at home alone wasn’t suitable for me anymore. She’d ensured me that it would be safer for me to be in a residence like this, as she called it. My heart problems mixed with the early onset of dementia are a dangerous concoction, it would seem.

Claire’s busy, too. Her job in marketing keeps her floating around from place to place, which is perhaps how old what’s-his-name she was married to escaped with his flighty heart. With her travelling so often for work, it would be impossible for me to live with her – not that I’d want to impose on her life like that. Thus, she’d pleaded and begged for me to move somewhere more suitable and somewhere closer to her so she could spend time with me when she was home.

I hadn’t wanted to give up my home in Harlow, of course. True, most days the place felt like a mausoleum or a shrine dedicated to a life I could no longer live. There wasn’t much left for me on Quail Avenue except struggles and uncertainties. Getting around was exceedingly more difficult, and keeping up with the empty, chilled house was no longer easy. Then, of course, there were the incidents the neighbours were quick to report to Claire – like they’ve never forgotten anything before. Things were never the same on Quail Avenue since Charles passed, but at least there, I had memories and familiarity. I had some remnants of my dignity and privacy. I had a sense of home.

I’d fought Claire for months about moving out, insisting I could handle myself. In truth, I suppose I wasn’t afraid of going out in the same house Charles did. Perhaps a piece of me thought that if we were connected in our manner of death, it would be a good omen for the next life – something I try not to think too much about. However, months of Claire’s nagging coupled with a few scary moments on my own finally managed to free me of my devotion to living alone. Perhaps it was also the fact I was so tired. It had all become way too much.

Nonetheless, coming back to Crawley, well, that hadn’t been easy. The heart palpitations seemed to worsen at the idea, an old fear resurfacing at the thought of stepping onto this haunted ground. I found myself evaluating what I was doing. Why had I even considered coming?

Claire, of course. To be near my daughter. I was willing to risk anything, to face any fears, to make her happy – and maybe I felt the need to protect her.

I’d always hated that Claire had settled down here, an area where I had lived in my late teen years. It had been one of the darkest periods of my life, a time I would do well to forget. Sometimes life is full of surprises, and not always in a good way.

After Charles died and Claire, in the middle of starting her life over again after her marriage fell apart, announced her move to Crawley, I almost collapsed.

‘What do you mean, Crawley?’ I had asked, my heart fluttering.

‘I just need a change, Mum. I need somewhere peaceful that’s still easy to commute from. I’ve found a lovely little flat in Langley Green in Crawley.’

I felt as though my heart was lodged in my throat. I’d protected Claire from the past for so many years. Charles and I didn’t talk about it. We’d moved on from Crawley and never, ever looked back. But to hear my adult daughter talking about those places – it was too much.

‘I don’t understand,’ I murmured, trying to maintain my composure.

Claire sighed, turning the cup of tea in her hands across the table from me. ‘Mum, don’t get angry. I know you and Dad don’t like to talk about those years in Crawley. I know it was complicated. But a few weeks before Dad died, I don’t know, I just got curious. I’m in my fifties, and I don’t know that much about you two, in truth. I never knew my grandparents. I know you didn’t like to talk about them, but it’s like the both of you wiped away your past. It was a hidden secret hanging over us. I got curious. Dad told me about Langley Green and how much he loved it there. He told me about how you two met, about how he would travel to West Green to visit you. He told me how much he loved you from the beginning. I don’t know, I guess after he died, I just felt like it was a sign. Maybe that’s where I’m meant to be. It seems like a good place to start over.’

Vomit rose in my throat. I tried not to cry. How could you, Charles? After so many years, you planted this idea in her head? Searing anguish I thought had died decades ago had risen in my chest.

‘What else did he say?’ I asked tentatively. Fears rose. But there are things even Charles didn’t know. There were secrets even Charles couldn’t tell.

‘The same thing you two always said when I asked you. “It was complicated.” Mum, I know Crawley was a dark place in those years. But I don’t know, I think I could be happy there. I think it would be nice to be somewhere strange yet familiar in a weird way. You lived in West Green, close to where I’ll be. Dad lived there. My grandparents, whom I never got to meet, lived there.’