Collins New Naturalist Library

Turning now to the pelage we find very useful characters to distinguish bulls and cows in the field. These features are, in fact, visible in the pigmentation of the skin of the foetus at a comparatively early age, namely at 110–120 days of active gestation. Growth of the white pup hair coat however obscures this pigmentation by the 150th day of foetal growth. This puppy coat is uniformly unpigmented except occasionally in the region of the muzzle and top of the head. The hair is very long and creamy white on the newly born pup. The occurrence of the greyish areas around muzzle and crown has been interpreted as part of the moult which has taken place before birth and only resumed later at about 3 weeks of age. The excuse for this belief lies in the peculiar hormonal situation existing in the pup at birth, but examination of the hair from these areas shows that the pigment is confined to the tops of the hair and that the hairs themselves are quite unlike those of the later moulter coat. No explanation of these greyish areas is yet available, and their occurrence is very odd. Some groups, notably Pembrokeshire, show a much higher incidence than others, such as the Farnes. Further, these areas are the first to show any hair in the foetus and the time of their eruption makes it clear that the tops must have been formed in the follicles before the appearance of any general pigmentation in the skin.

The pup may begin to moult as early as the 10th day, but this is most unusual and it is generally the 18th day before the first signs appear on the fore and hind flippers and on the head. If the pup belongs to a group such as the Pembrokeshire where entering the sea is a common occurrence, much of the moulting hair is washed off and, as the puppy coat becomes thinner, the pattern of the moulter coat shows through. Even here, however, many of the pups do not enter the sea during the moult and in the northern groups, of course, this is the usual pattern of behaviour. Under these conditions the puppy coat is rubbed off in patches and often the moulter can be found lying on a carpet of its old hair.

This moulter coat is to all intents and purposes the same as all the subsequent coats, heavily pigmented on the back and sides at least and marked by even darker spots and blotches. It is in the abundance and distribution of the darker spots that the difference between bulls and cows can be seen. In cows the lighter pattern consists of a medium grey back shading to a lighter belly, the darker spots are comparatively few and only rarely run together. In the bulls the darker pattern is so extensive that the lighter one is seen only as small triangular patches between the dark spots and blotches which have run together over most of the body.

There is, however, considerable variation in both sexes. In the cows the pale underside may be any colour from pale cream to tawny yellow and the upperside may vary from grey or blue-grey to brown. Some cows may have very considerable blotching, but never to the extent shown in the bulls. In bulls the chief variation is in the overall tone of the darker pattern which may be dark brown to black in colour. A number of older bulls too show a markedly lighter head and sometimes the blotches unite so much as to give the impression of uniform black or dark brown.

These remarks of course apply to the new coat which is grown each year. As the time of moult approaches the whole pelage becomes duller, browner and more uniform in appearance due to the splitting of the hairs so that it is only in the wet pelt that the patterns can be distinguished. It should always be borne in mind when observing grey seals on shore that the appearance of the pelage alters considerably as it dries and that the change is more marked as the moulting season approaches.

The disparate growth of the bulls and cows is well seen in the skull and reflected in their profiles. The skull of the grey seal has a long flat vault which clearly distinguishes it from that of the common seal where the shorter, rounder vault gives rise to the dome-like head. The nasal bones too are differently placed so that the grey seal has, in the bull, a ‘roman’ nose profile and in the cow a straight or ‘grecian’ profile, while the common seal in both sexes shows a slight depression or ‘retroussé’ nose (Fig. 11). The young grey seal however has a skull very similar in appearance to that of the common seal and to that it owes its puppyish look. Within the first year the specific elongation and flattening of the skull takes place and there is little difficulty in distinguishing the two species in the field.

As grey seals grow older these characteristics are accentuated. At 5–6 years of age the sutures between the frontals, parietals, squamosals and occipitals fuse but the anterior sutures between frontals, nasals and premaxillae remain free throughout life and some increase in both length and breadth of the skull continues. In some of the oldest of the cows the profile may begin to take on a ‘roman’ bend, just as the young bulls approaching puberty still have such a straight profile that their identification by this character alone is by no means sure.

The teeth of the grey seal are very distinctive and unlike those of any other phocid. The formula is normally

FIG. 11. External differences between common and grey seals and between grey seal bulls and cows. Between grey and common seals the position of the nostrils is diagnostic and also the domed and rounded head of the common. Between grey seal bulls and cows the profile is the most certain distinguishing feature when only the head is visible above water. Common seal bulls and cows are almost impossible to separate by head features alone.

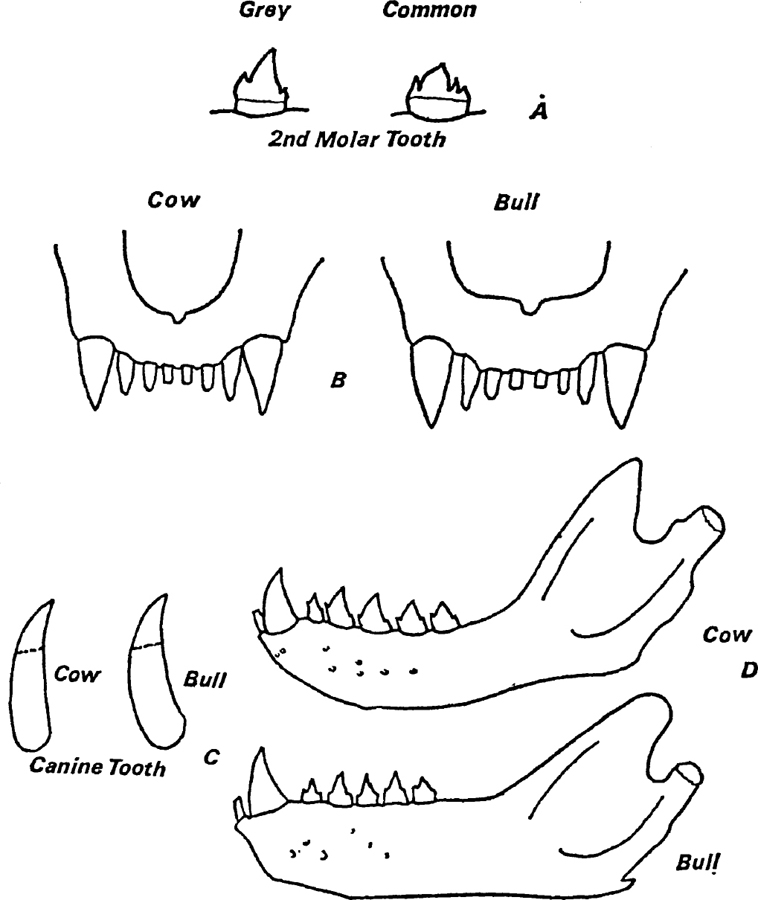

In the bulls the canines are much larger than in the cows. Not only are they heavier, but the root is more bulbous. It is quite possible to sex an isolated lower jaw of any animal over the age of 5 years by the shape of the canine tooth. In the bulls the upper incisors are also broader and this results in a greater width between the canines. Externally these features unite in producing a broader muzzle and a greater gap between the nostrils in the male. The breadth of the male muzzle is further accentuated by the massive pads on which the vibrissae are mounted (Fig. 12).

FIG. 12. Jaws and teeth in the common and grey seals, A. shows the differences in the molar teeth of common and grey seals, B. shows the markedly broader muzzle in the bulls, C. shows the greater curvature in the canine teeth of bull grey seals, D. shows the greater depth in the lower jaw of bull grey seals. Both jaws are drawn to the same length.

The position and arrangement of the nostrils are also diagnostic features distinguishing grey from common seals. In the latter the two nostrils almost meet at their most anterior and ventral point and diverge above this at a distinct angle. In the grey seal the nostrils are almost parallel and their anterior ventral points are separated by a large pad of skin (Fig. 11).

The grey seal is highly vocal, particularly the cow. All aggression by cows, if only jostling for position in a haul-out, is accompanied by high-pitched hooting which has a peculiar quavering quality, partly of pitch and partly of volume. This hooting often carried out by several cows at once produces a weird sound which has been called ‘singing’ but it is far from singing at its best! The bulls are capable of a snarling hiss which also has a guttural quality. However, often in mild aggression they do no more than open their mouths and emit an exhalation which is almost soundless. The high pitched voice of the pup is described later (See here).

There are many parts of Britain where the species of seal present can be almost certainly determined by the habitat. Thus, as Fraser Darling has said, the common seal on the west coast of Scotland is a sea-loch seal, the grey a seal of the outer islands and the strong Atlantic seas. And again on the Essex coast the mud and sand flats are typical haul-out sites for common seals, while the rock-bound coasts of west Wales provide typical grounds for the grey. Nevertheless it is not possible to generalise completely. Certainly the grey seal uses habitats which would rarely be used by common seals, isolated skerries and islands swept by Atlantic gales and surrounded by tidal rips which throw the sea into tumultuous heaps. The common seal will use estuarine waters and the mud and sand banks associated with them where the grey would never go. Yet between these extremes there are many habitats which both use. Many of the haul-outs in Orkney and Shetland are mixed, although of course the breeding grounds never are.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов