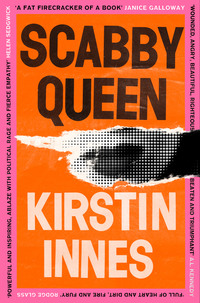

Scabby Queen

‘Dearie me!’ Clio said, pulling a face, covering up. A couple of mild chuckles rose from the people around him. He wanted to let her know that they were with her, that they were on her side. ‘Shall we try that again, boys?’

She counted down again, and this time the guitar was fine, twangy but fine, sliding out chords that sounded faintly familiar to him, although he couldn’t work out from where. Then Clio began to sing, the slow rasping warmth of her starting somewhere near his stomach, flooding out and through him till his hair crackled with her, even on that crappy PA system.

‘O, Danny boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling.’

Under her lashes, she glanced off to the side, where the tour manager was standing, winked for a fraction of a second, something like a smile working on her, dimpling the words. Her skin seemed to be beaming in the light.

Proper fanny-magnet, Danny-boy.

She played for the promised just-over-an-hour. Rocked-up versions of the auld songs, folk-tinged covers of some recent hits – ‘Joyride’, ‘Losing My Religion’ – and only three of her own tunes. Neither of the two new ones were particularly memorable; slow and acoustic, the other musicians stepping aside to stare at their feet or smoke. Her voice is like whisky, he jotted in shorthand, in the dark, reminding himself to follow up on that later. In between songs, she tried to engage the audience, anger them, as though they were a rally crowd, with lists of the Tory government’s crimes and how they themselves, the people of Ullapool and their children, were being affected. The audience was silent, impatient for her to start singing again, like sleepy junkies focused only on the delayed gratification of the next hit. She finished, of course, with ‘Rise Up’. The teenagers in the back row started whooping and singing along, and she even managed to get the more sedate audience members up the front clapping their hands for a final a cappella take on the chorus.

As soon as the music stopped, she seemed tiny, confused. She bowed twice, muttered ‘Thank you, Ullapool’ into the microphone, then ploughed offstage by the door to her right, as the applause died away. Duncan flicked the light back on, and the room emptied quickly.

Clio had been given the community hall’s kitchen as her dressing room. It was wincingly bright. Guitar cases were balanced on cabinets; a make-up bag spilled over the small electric hob. The band leaned around, cans in hand; Clio was perched on a flimsy-looking table, feet on the room’s sole plastic chair, swigging from a bottle of red wine.

‘No. It was shit, it was shit, it was shit,’ she was saying, pausing to top herself up. ‘Fucksake, what a bunch of fucking stiffs. Giving me nothing, so of course I fucking froze. Neil! Neil Neil Neil – Neil’s here!’

She stretched out her arms towards him and he mock-ran towards her, mugging.

‘Here you are, here you are. I was so worried when you didn’t show, but Danny said you’d be fine.’

The hug was tight and real, her arms over his, taking all of him in.

‘Argh! It’s been so long.’

‘Thank you for doing this, my darling. Really. I’m so sorry you had to see the show on such a terrible night. That audience, eh? My God. The other nights have been so much better – tell him, Donald.’

The big bear man with the beard who had played accordion and fiddle nodded towards him, silently, while the sallow drummer piped up, in a thick Scouse accent. ‘Yeah – the crowd in – what was that place? Durness? Like nothing I’ve ever seen before.’

‘I think they liked it,’ Neil said. ‘They were maybe just more naturally reserved – there’s a few of them still hanging out there, waiting to meet you.’

‘Ah, fuck ’em. Not tonight. Tonight I’m going to stay here in my strip-lit kitchen prison and drink wine with my old pal Neil.’ She had grabbed his hand and was swinging it, smiling hugely and slightly drunkly at him.

Danny stepped forward. He’d been so still until that point that Neil hadn’t really registered he was in the room.

‘Come on, Clio. That’s not the deal. That’s not what we agreed.’

‘Danny—’

‘No, you know the score. You made up the score, in fact. The point of this tour is that you get out there and you communicate with people. On their own level. You’ve got half an hour. Then we can go to the pub and you can catch up with Neil. I’m sure he understands.’

Neil found himself nodding, trying to please teacher.

Clio held up the hand that was not clutching the bottle.

‘All right. All right.’

Danny poured some of the wine – a polite amount – into a small paper cup. It had already left a thick purple crust over her lipstick. He ushered her out with a hand on the small of her back, left Neil alone in the kitchen with the band.

‘That really was a great show tonight, guys,’ he said, into the silence.

‘It weren’t our best,’ said the guitarist, also Scouse.

‘It weren’t bad, though,’ said the drummer. ‘She’s being hard on ’em is all.’

Of the three, the drummer had the most alert face. Big round eyes in a bouncing head, like a friendly children’s puppet. He took a couple of jerky steps over to Neil and held out a hand to shake. ‘Lee. Hiya. So, you’re a pal of Clio’s?’

‘This is the journalist,’ the other one, the guitarist, said. ‘This is the boy that’s coming on the road with us.’

‘Oh, right! That’s you, then. Pretty handy that, that you’re a mate of Clio’s an all, eh? Neil, is it? That’s Sean, there, and the big fella here is Donald. He don’t talk much, but he’s sound, aren’t you, mate?’

Neil just nodded. He honestly couldn’t think of anything to say.

‘Anyway, you’re in with us tonight,’ Lee was saying, trying to invite him in. ‘Pretty cosy arrangement we’ve got! Donald here snores a bit – don’t you, big lad – but you get used to it.’

Neil thought about Clio out there with the straggling autograph hunters, wondered if she was talking to them about politics, or if they’d got bored and gone home. He thought about how small she’d seemed out there on the stage.

‘So. Lee – how did you meet her?’

‘Clio? Oh yeah, yeah. Me and Sean are in a band of our own, see, and she was on before us at this massive poll tax rally in Liverpool – that were the night she got signed, weren’t it, lad? A&R fella was there. We all went out to the pub after and, ah, a few ales were consumed, shall we say, and we’ve all been pals since. Amazing gel, int she? Proper, like. We played some more rallies together, and then when “Rise Up” went all massive she had us come and be her band a couple of times. Did you see Top of the Pops? That were us, eh.’

‘Closest we’ll ever get,’ muttered Sean.

‘Yeah, she looks after her own, that gel. So she said she wanted to do this tour and would we come; well, me and him were doing fuck all in Liverpool, like, and we’ve never been to Scotland before, have we? Sean’s looking forward to the Isle of Skye and Orkney, aren’t you?’

Sean nodded. ‘I’m into ancient monuments, like.’

At this, the older man, Donald, got up and left the room, nodding to them all.

‘Ah, don’t mind him, like,’ said Lee, with a conspiratorial smile, and Neil wondered what he’d done to attract the unswerving devotion of this puppy-dog. ‘He’s just a bit shy with new people is all. Man’s magic with a fiddle, like. You hear all those folk arrangements, on the R.E.M. song? That’s all Donald. Him and Clio go way back, far as I can make out. Like, she’s known him since she was a kid. That sort of thing.’

‘Hoi, soft lad,’ said Sean. ‘Don’t go sharing everyone’s life story when they’re at the bogs, eh?’

‘Sorry,’ said Lee, his smile getting even wider. ‘I love a gossip, me.’

Neil coughed, tried to make his face seem friendly, finally had the breathing space to say the thing he’d been bursting for.

‘I might head back through there – see how she’s getting on. You boys coming?’

Some of the plastic chairs from the auditorium had been rearranged into a loose circle that Clio somehow managed to be at the head of. As the door creaked she looked up and called to them.

‘Come in! Come in! Come and join the body of the kirk!’

The teenagers from the back row were sitting on either side of her, gazing in. An older couple, who had shyly put themselves at a distance, were gradually unfurling under Clio’s beam; the woman had kicked off her heels and tucked her feet up under herself. Irene from the bar table was there too; and little spotty Duncan, sitting admiringly by Danny, who had pulled himself slightly out from the group, was watching Clio with a tiny smile.

‘So,’ she said, beaming up at Neil as he and the Scousers fumbled for extra chairs. ‘We’re just discussing the first records we all bought. Siobhan here,’ she indicated the teenage girl, ‘actually says hers was “Rise Up”, can you believe it? Her taste in music has got way better since then, though, hasn’t it, Siobhan? What about you, Dorothy? It is Dorothy, isn’t it? I thought it was. Just wanted to make sure. What was the first record you ever bought?’

Round the circle she went, glitter in her smile, everyone blooming. He noticed that the lipstick situation had been sorted, and also that no one else got to talk for too long. Clio was the conductor. Donald moved silently around behind them, packing up the instruments, reeling in the wiring. At one point he ambled over and touched Danny on the shoulder, and the promoter got up to help him. Clio continued to talk, about nothing much, bursting into that peal of a laugh often, steering well clear of the brimstone of her stage chat, and the room danced.

Danny broke the spell. ‘Right, that’s us all packed, and we really need to be letting poor Irene here get locked up and away to her bed.’

Irene tried to protest (‘Och no, I don’t mind, son’), but Neil had a feeling that Danny Mansfield always got his own way.

‘Shall we head up to the Argylle Bar, Clio? And anyone who wants to can join us – provided they’re old enough, of course.’

Neil lay in the top bunk, under his sheet sleeping bag and big Donald’s long wool coat, with a bladder over-full of beer and no idea what to do about it. It had taken him a suitcase balanced on a table and a leg-up from a swaying, friendly Lee to get into the bed in the first place, as there were no ladders provided in this bunkhouse, apparently, and the bunks were not designed for short people. There were actually two bottom bunks free, but one had everyone’s luggage heaped on it, and the other one, he was told, was Danny’s. Well, he’d been in bed for almost three hours now, marking the passage of time by Donald’s gentle snoring and Lee’s occasional whimpers, and Danny had not decided to make use of his bunk yet.

Fuck it. He would go to the toilet, take that bottom bunk on his return, and if Danny came in he could get himself up into Neil’s bed somehow. He cantilevered himself off the side, his feet scrabbling air for the safety of the bunk below. For one horrendous second he thought he was going to fall, but then his toe caught the mattress, the strap of a rucksack.

The floor in the corridor was freezing, but it was too dark in the room to look for socks. He hadn’t thought to bring pyjamas, either, so faced the long walk in his T-shirt and pants, hoping it was late enough that no one would see. He passed Clio’s door, number 28. She was the only person on the tour to get a room to herself, it seemed. Tiny sounds from back there: a woman whispering, a man laughing, a soft moan.

Well, what were you expecting, he thought to himself, breathing in cheap, sharp disinfectant that didn’t mask the smell of someone else’s shit, as he clenched his bare feet in front of the urinal. You knew what she wanted you here for, and it wasn’t ever going to be that. She’s a beautiful woman. Beautiful women take lovers. He’d just never worked out why the lovers they took had to be such total arseholes.

In the bar earlier, Danny had oiled the conversation, buying rounds of drinks for everyone out of the tiny jar of takings from that night, kept everyone up, egged them on, determined, it seemed – he definitely wasn’t imagining it – to keep Neil from getting any sort of meaningful time with Clio. Was he jealous? A man like that, the satyr, the fanny-magnet, jealous of someone like Neil? Perhaps he sensed Neil’s connection with Clio – perhaps that was getting to him. He couldn’t imagine there was much going on between them besides shagging. Danny didn’t seem the socialist sort to him, didn’t seem like he had any convictions at all beyond the getting of money. Greasy prick. Oh, he’d do well in life, Neil had no doubt.

In his anger, Neil had forgotten to shake himself, had to climb the stairs and hobble his way back along the corridor with his hands cupped over the slow-blooming stain on his crotch. He was about to turn the corner, but a shaft of light cut through his vision and he froze against the wall. A female figure, silhouetted, some loose thin thing flowing over her upper body, doubling and pulling back. The pointed goatee. The hooves. Neil was sure he could see cloven feet. The small sound of a kiss, the click of a door as the light shut off. Danny was lying in the lower bunk by the time Neil got down the corridor, apparently asleep.

Their days on tour, in a beaten-up old minibus that had been the property of a community centre, had a particular rhythm. The two Scouse boys lolled along the back seat, lost together, talking their own codes, passing a joint back and forth. Between that and the sharp smell of last night’s whisky from everyone’s breath, the air in there was overbearing. Neil cracked a window whenever he could, but the wind was too much if they were on the motorway. The boys would get restless if they hadn’t had a drink by two, so pubs and off-licences needed to be sought out regularly. They raided garages for crisps and sweets, all of them eating like children let loose on a tuck shop.

As they drove, Clio consumed newsprint like food, stocking the bus with five papers every day, occasionally ripping out stories, tutting and exclaiming, fizzing with anger. Nobody really spoke. Neil and Clio had had a bit of a gossip, sure, the first time she was sitting in the back with him – she’d asked after Gogsy ‘or the Right Honourable Member, as I hear we’re now to call him. Labour Party, eh? Who’d have guessed?’ (wink) and his new wife – but they were both too conscious of the silence, the four other people right there, listening in, to say much.

For two days, whenever they arrived at their next location, Clio would take her musicians straight to the venue. Neil thought it would be interesting for his article to sit in there, but Danny had suggested it might make Clio nervous.

‘At some point,’ Neil told Danny, on the morning of the third day, ‘I’m going to need some time just the two of us. Me and her. This piece is nothing without the interview – I can’t just turn in an extended gig review, you know. And I’m only here till Sunday.’

Danny’s body language was big, expansive. His hands patted the air between them, soothed it.

‘It’s cool, it’s cool, amigo. I know that. Let me have a word with her and see what we can sort out, eh?’

Onstage, though. When she was onstage, he felt like he was working. It was the only time his mind could focus on the article, push ideas around. It was fascinating, watching her night after night, the way she tried to take the temperature of the audience and adjust herself around them; the way she didn’t always succeed.

The night after Ullapool had been Oban. The big upstairs function suite of a pub, bar and clientele both built in. Danny took the stage, asked for a very warm Ochil Bar welcome for An Evening With the beautiful, the mind-blowingly talented … and she stepped in front of the mic and just stood there. No shy smile, no hello Oban. The band around her totally still, and then Donald began knocking out a slow, sturdy heartbeat, bare knuckles on the wood of his fiddle.

Her voice, then. More ragged than usual – the after-effects of the long, slow toke she’d taken of the boys’ joint in the bus, maybe, her eyes daring Neil to comment.

‘Is there for honest Poverty

That hings his head, an’ a’ that;

The coward slave – we pass him by,

We dare be poor for a’ that!’

Sean joined her on the chorus, a honey tenor harmony.

‘For a’ that, an’ a’ that.

Our toils obscure an’ a’ that,

The rank is but the guinea’s stamp,

The Man’s the gowd for a’ that.’

A couple of bearded older blokes in the row in front of Neil picked up the beat and it spread slowly through the crowd, their feet moving as one. The room crackled. Lee met the thump with the bass drum, allowing Donald to raise his arms, draw single notes off the fiddle into the air.

‘For a’ that, and a’ that,

Their tinsel show, an’ a’ that;

The honest man, tho’ e’er sae poor,

Is king o’ men for a’ that.’

Donald sang the next verse with her, a husky bass rasp that echoed under Clio’s sweet-and-sour. From the back row came a wavering note of soprano, growing stronger as the people around her smiled encouragement. Clio stretched out an open hand. And then they were all singing together, the whole room, even those who didn’t know the words joining in at the refrain.

‘For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

It’s comin yet for a’ that,

That man to man the warld o’er

Shall brithers be for a’ that.’

Neil would hear Burns, and that song in particular, performed many times over the years. In 1992, though, it was still unfashionable. Tartan tat, the stuff of shortbread tins and fat conservative men at Rotary Club suppers. He still thought the spirit in that room had never been equalled.

As the storm of applause didn’t seem to be dying down, Clio spoke over them.

‘Robert Burns, Oban. A true radical. A revolutionary. And born just half an hour up the road from where I grew up, in Ayrshire. Hello, Oban. I’m Clio Campbell. And I’ve got something to say.’

Back in the bed-and-breakfast, Neil put a pillow over his head to muffle the noise of Clio and Danny’s celebration in the room next door.

The next night, though, a working men’s club in Fort William, their hangovers still pulsing, the room cold from a draughty window and only a quarter full because the football was on, no one stamped, no one sang, and Clio drank and swore and tainted the air around them in the pub afterwards. The cut seemed all the deeper for what had gone before, and Neil eyed his travelling companions round the table unsure of how on earth they’d get her out of it.

‘Look,’ he said, eventually. ‘You’ve still got last night, right? It doesn’t matter that this one wasn’t your best. You’ll always have Oban!’ It was intended as a joke, but the reaction was seismic.

‘It wasn’t my best, was it. Oh God. I should have engaged them more – that sort of cold open is sometimes a mistake; I should have been able to see that they needed warming up. God, I call myself a professional at this, but I’m so fucking inexperienced really. Ah, man, why did I ever think this was possible? A month-long tour! A fucking month! I want to go home.’

The other men at the table were frowning, looking away from him. Lee had reached over to stroke her shoulder.

‘Hey, la. You listen up. You were bloody great tonight, all right? This is some shit you’re talking now. You had a small crowd freezing their bollocks off, and you gave them a show. You gave them a helluva show. Their own lookout if they couldn’t appreciate it, eh?’

‘This boy knows what he’s talking about,’ said Danny, thumping the table. ‘No more of this sort of chat, now. They’re lucky to have you.’

‘Aye, you were damn good tonight, sweetheart,’ said big Donald, mumbling through his beard.

At the bar, a little later, Danny tapped Neil on the elbow, smiled at him.

‘Listen, man, don’t worry about earlier. It’s just an artist thing, you know? When they come offstage they’re like great gaping wounds, basically – need to be treated very carefully. You know? Always better just to tell her she was wonderful, yeah?’

He was smiling. He was perfectly, totally reasonable. But Neil understood that he was being told off, that a flag had been raised.

‘Yeah, yeah. Got it. Sorry, man. Yeah.’

‘Good boy. Let me get this round, eh?’

All that night, back in his single room in the hotel, much nicer than anywhere else they’d stayed, Neil had fumed. They had begged him – begged him – to come on this tour. She had. She wanted this article. Made him wrangle with his editor, pitch harder than he’d ever pitched a piece before. Brought him here, away from work for the best part of a week. And what did she expect him to write, exactly? Two thousand glowing words about the landscape and the timbre of her voice? ‘Drinking Dens of Highland Towns: A Comparative Study’?

The next morning, he’d hung around in the breakfast room until Danny had come in, then taken a seat opposite him. Made his demands: interview. Now. Danny had patted the air again, looked genuinely worried, and Neil had climbed back upstairs to pack his holdall, feeling that the scale had finally been reset in his favour.

Clio and the boys were in the lobby, lounging about on sofas too well-upholstered for them when he came to check out, surrounded by their luggage and instruments. Her Doc Martens rested on a coffee table, and it was impossible to tell whether she was awake or not through her sunglasses; Sean was glaring at the world through a particularly greasy fringe, and Lee appeared to be skinning up on the back of a glossy magazine.

‘Morning, lad. There’s a bit of a hold-up, eh – Donald and Danny had to go and take the little bus to the bus hospital,’ he said, still cheery. ‘I’d go get yourself a cuppa if I was you – if you’re going over could you grab me a Bloody Mary, too?’

Neil smiled. ‘I’m all right just now, pal, but thanks for the concern.’

Lee beamed at him. ‘God loves a trier, mate. Actually, it’s good you’re here. With four of us we can get a proper game going.’ He shoved the pile of ripped-up Rizlas to one side and pulled a grubby deck of cards from the pocket of his cagoule.

‘Card games,’ said Clio, from behind the shades.

‘Very well observed, that woman. What does everyone fancy? Quick round of rummy?’ Lee’s skinny fingers rippled and shanked the cards.

‘Watch him. He’s a shark,’ muttered Sean.

‘Texas poker? Scabby Queen? Blackjack?’

Clio pulled her shades off, turned to face him.

‘What did you say?’

‘Blackjack?’

‘Before that.’

‘Scabby Queen?’

‘Yeah.’

‘You never played it? It’s a good one, that. You play with an almost full deck, except there’s only one queen in it, and she’s hidden in there somewhere. Everyone gets a full hand – that’s why you need at least four, see, otherwise there’s too many cards – and you take it in turns in drawing from each person’s pile. Every time you get a pair, they’re coupled off and taken out of play. The queen goes round and round, and the object is to get rid of her – pass her on to the next one as quickly as you can. Person left with the queenie at the end loses, you see. Poor girl, int she. And the guy left holding her – he gets hit over the knuckles with the full deck. Papercuts and all. Can get a bit scabby, like.’

Clio laughed. It sounded a bit forced.

‘I’m from a mining town, hon. That means something pretty different back home, that does. Or maybe not.’ She breathed out. ‘Anyway, I hate to spoil your bridge party, but me and Mr Munro here are going to use this time to conduct our all-star celebrity interview. Away from your nosy face.’

She pinged one of Lee’s ears with affection.

‘Fancy holing up in the bar, Neilio? I’m sure the sun’s over the yard arm somewhere. All that talk of Bloody Mary has me thirsty. Bloody Clio time.’