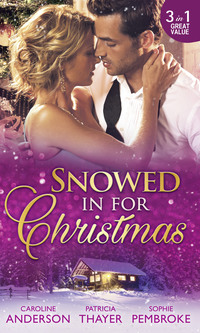

Snowed In For Christmas

It was far worse than he’d realised. There were no huge, fat flakes that drifted softly down and stayed where they fell, but tiny crystals of snow driven horizontally by the biting wind, the drifts piling up and making the lane impassable. He wondered where the hell she was. It would have been handy to know just how far along—

And then he saw it, literally yards from the end of his drive, the red tail lights dim through the coating of snow over the lenses. He left the car in the gateway and got out, his boots sinking deep into the powdery drifts as he crunched towards her. No wonder she was stuck, going out in weather like this in that ridiculous little car, but there was no way she’d be going anywhere else in it tonight, he realised. Which meant he would be stuck with her.

Damn.

He felt anger moving in, taking the place of shock. Good. Healthy. Better than the sentimental wallowing he’d been doing last night in that damn four-poster bed—

Bracing himself against the wind, he turned his collar up against the needles of ice and strode over to it, opening the passenger door and stooping down. A blast of warmth and Christmas music swamped him, and carried on the warmth was a lingering scent that he remembered so painfully, excruciatingly well.

It hit him like a kick in the gut, and he slammed the lid on his memories and peered inside.

She was kneeling on the seat looking at something in the back, and as she turned towards him she gave him a tentative smile.

‘Hi. That was quick. I’m really sorry—’

‘Don’t worry about it,’ he said crisply, trying not to scan her face for changes. ‘Right, let’s get you out of here.’

‘See, Josh?’ she said cheerfully. ‘I told you he was going to help us.’

Josh? She had a Josh who could dig her out?

‘Josh?’ he said coldly, and her smile softened, stabbing him in the gut.

‘My son.’

She had a son?

His heart pounding, he ducked his head in so he could look over the back of the seat—and met wide eyes so familiar they seemed to cut right to his soul.

‘Josh, this is Sebastian. He’s going to get us unstuck.’

He was? Well, of course he was! How could he refuse those liquid green eyes so filled with uncertainty? Poor little kid.

‘Hi, Josh,’ he said softly, because after all it wasn’t the child’s fault they were stuck, and then he finally let himself look at Georgie.

She hadn’t changed at all. She had the same wide, ingenuous eyes as her son, the same soft bow lips, high cheekbones and sweeping brows that had first enchanted him all those years ago. Her wild curls were dark and glossy and beaded with melted snow, and there was a tiny pleat of worry between her brows. And her face was just inches from his, her scent swirling around him in the shelter of the car and making mincemeat of his carefully erected defences.

He hauled his head out of the car and straightened up, sucking in a lungful of freezing air. Better. Slightly. Now if he could just nail those defences back in place again—

‘I’m really sorry,’ she began again, peering up at him, but he shook his head.

‘Don’t. Let’s just get your car out of here and get you inside.’

‘No! I need to get to my parents!’

He let his breath out on a disbelieving huff. ‘Georgie, look at it!’ he said, gesturing at the weather. ‘You’re going nowhere. I don’t even know if I can get your car out, and you’re certainly not taking it anywhere else in the dark.’

‘It’s not dark—’

‘Almost. And we haven’t got your car out yet. Just get in the driver’s seat, keep the engine running and when you feel a tug let the brakes off and reverse gently back as I pull you. And try and steer it so it doesn’t go in the ditch. OK?’

She opened her mouth, shut it again and nodded.

Plenty of time once the car was out to argue with him.

* * *

It took just moments.

The car slithered and slid, and for a second she thought they’d end up in the ditch, but then she felt the tug from behind ease off as they came to rest outside the gates and she put the handbrake on and relaxed her grip on the wheel.

Phase 1 over. Now for Phase 2.

She opened the car door and got out into the blizzard again. He was right there, checking the side of her car that had been wedged against the snowdrift, and he straightened and met her eyes.

‘It looks OK. I don’t think it’s damaged.’

‘Good. That’s a relief. And thanks for helping me—’

‘Don’t thank me,’ he said bluntly. ‘You were blocking the lane, I’ve only cleared it before the snow plough comes along and mashes it to a pulp.’

She gulped down the snippy retort. Of course he wasn’t going to be gracious about it! She was the last person he wanted to turn out to help, but he’d done it anyway, so she swallowed her pride and tried again. ‘Well, whatever, I’m still grateful. I’ll be on my way now—’

He cut her off with a sharp sigh. ‘We’ve just had this conversation, Georgia. You can’t go anywhere. Your car won’t get down the lane. Nothing will. I could hardly pull you out with the Range Rover. What on earth possessed you to try and drive down here in weather like this anyway?’

She blinked and stared at him. ‘I had to. I’m on my way home to my parents for Christmas, and I thought I’d beat the snow, but it came out of nowhere and for the last hour I’ve just been crawling along—’

‘So why come this way? It’s hardly the most sensible route in that little tin can.’

She bristled. Tin can? ‘I wasn’t coming this way but the other road was closed with an accident—d’you know what? Forget it!’ she snapped, losing her temper completely because absolutely the last place in the world she wanted to be snowed in was with this bad-tempered and ungracious reminder of the worst time of her life, and she was seriously leaving now! In her tin can! ‘I’m really sorry I disturbed you, I’ll make sure I never do it again. Just—just go back to your ivory tower and leave me alone and I’ll get out of your hair!’

She tried to get back in the car, desperate to get away before the weather got any worse, but his hand shot out and clamped round her wrist like a vice.

‘Georgia, grow up! No matter how tempted I am to leave you here to work it out for yourself—and believe me, I am very tempted at the moment—I can’t let you both die of your stubborn, stiff-necked stupidity.’

Her eyes widened and she glared at him, trying to wrestle her arm free. ‘Stubborn, stiff-necked—? Well, you can talk! You’re a past master at that! And we’re not going to die. You’re being ridiculously melodramatic. It’s simply not that bad.’

It was his turn to snap then, his temper flayed by that intoxicating scent and the deluge of memories that apparently just wouldn’t be stopped. He tugged her closer, glowering down into her face as the scent assailed him once more.

‘Are you sure?’ he growled. ‘Because I can leave you here to test the theory, if you insist, but I am not leaving your son in the car with you while you do it.’

‘You can’t touch him—’

‘Watch me,’ he said flatly. ‘He’s—what? Two? Three?’

The fight went out of her eyes, replaced by maternal worry. ‘Two. He’s two.’

He closed his eyes fleetingly and swallowed the wave of nausea. He’d been two...

‘Right,’ he said, his voice tight but reasoned now, ‘I’m going to unhitch my car, drive into the entrance and hitch yours up again and pull you up the drive—’

‘No. Just leave me here,’ she pleaded. ‘We’ll be all right. The accident will be cleared by now. I’ll turn round and go back the other way—’

His mouth flattened into a straight, implacable line. ‘No. Believe me, I don’t want this any more than you do, but unlike you I take my responsibilities seriously—’

‘How dare you!’ she yelled, because that was just the last straw. ‘I take my responsibilities seriously! Nothing is more important to me than Josh!’

‘Then prove it! Get in the car, shut up and do as you’re told just for once in your life before we all freeze to death—and turn that blasted radio off!’

He dropped her arm like a hot brick, and she got back in the car, slammed the door unnecessarily hard and a shower of snow slid off the roof and blocked the wipers.

‘Mummy?’

Oh, Josh.

‘It’s OK, darling.’ Hell, her voice was shaking. She was shaking all over—

‘Don’t like him. Why he cross?’

‘He’s just cross with the snow, Josh, like Mummy. It’s OK.’

A gloved hand swiped across the screen and the wipers started moving again, clearing it just enough that she could see his car in front of her now, pointing into the gateway. He was bending over, looking for the towing eye, probably, and seconds later he was dropping a loop over the tow hitch on his car and easing away from her.

She felt the tug, then the car slithered round and followed him obediently while she quietly seethed. Behind them she could see the gates begin to close, trapping her inside, and in front of them lights glowed dimly in the gloom.

Easton Court, home of her broken dreams.

Her prison for the next however long?

She should have just sat it out in the traffic jam.

CHAPTER TWO

HE TOWED HER all the way up the drive and round into the old stable yard behind the house, and by the time he pulled up he’d got his temper back under control.

Not so the memories, but if he could just keep his mouth shut he might not say anything he’d regret.

Anything else he’d regret. Too late for what he’d already said today, and far too late for all the words they’d said nine years ago, the bitterness and acrimony and destruction they’d brought down on their relationship.

All this time later, he still couldn’t see who’d been right or wrong, or even if there’d been a right or wrong at all. He just knew he missed her, he’d never stopped missing her, and all he’d done about it in those intervening years was to ignore it, shut it away in a cupboard marked ‘No Entry’.

And she’d just ripped the door right off it. She and this damned house. Well, that would teach him to give in to sentiment. He should have let it rot and then he wouldn’t have been here.

So who would have rescued them? No-one?

He sucked in a deep breath, got out of the car and detached the tow rope, flinging it back into the car on top of the shovel just in case there were any other lunatics out on the lane today, although he doubted it. He could hardly see his hand in front of his face for the snow now, and that was in the shelter of the stable yard.

Dammit, if this didn’t let up soon he was going to be stuck with her for days, her and her two-year-old son, with fathoms-deep eyes that could break your heart. And that, more than anything, was what was getting to him. The child, and what might have happened to him if he’d not been there to help—

‘Oh, man up, Corder,’ he growled to himself, and slammed the tailgate.

* * *

‘OK, little guy?’

She turned and looked at Josh over her shoulder, his face all eyes and doubt.

‘Want G’annie and G’anpa.’

‘I know, but we can’t get there today because of the snow, so we’re going to stay here tonight with Sebastian in his lovely house and have an adventure!’

She tried to smile, but it felt so false. She was dreading going inside with Sebastian into the house that contained so much of their past. It would trash all her happy memories, and the tense, awkward atmosphere, the unspoken recriminations, the hurt and pain and regret lurking just under the surface of her emotions would make this so difficult to cope with, but it wasn’t his fault she was here and the least she could do was be a little gracious and accept his grudging hospitality.

She glanced round as her nemesis walked over to her car and opened the door.

‘I’m sorry.’

They said it in unison, and he gave her a crooked smile that tore at her heart and stood back to let her out.

‘Let’s get you both in out of this. Can I give you a hand with anything?’

‘Luggage? Realistically I’m not going anywhere tonight, am I?’ She said it with a wry smile, and he let out a soft huff of laughter and started to pick up the luggage she was pulling from the boot.

He wondered how much one woman and a very small boy could possibly need for a single night. Baby stuff, he guessed, and slung a soft bag over his shoulder as he picked up another case and a long rectangular object she said was a travel cot.

‘That should do for now. I might need to come back for something later.’

‘OK.’ He shut the tailgate as she opened the back door and reached in, emerging moments later with Josh.

Her son, he thought, and was shocked at the surge of jealousy at the thought of her carrying another man’s child.

The grapevine had failed him, because he hadn’t known she’d had a baby, but he’d known that her husband had died. A while ago now—a year, maybe two. While she was pregnant? The jealousy ebbed away, replaced by compassion. God, that must have been tough. Tough for all of them.

The boy looked at him solemnly for a moment with those huge, wary eyes that bored right through to his soul and found him wanting, and Sebastian turned away, swallowing a sudden lump in his throat, and led them in out of the cold.

* * *

‘Oh!’

She stopped dead in the doorway and stared around her, her jaw sagging. He’d brought her into the oldest part of the house, through a lobby that acted as a boot room and into a warm and welcoming kitchen that could have stepped straight out of the pages of a glossy magazine.

His smile was wry. ‘It’s a bit different, isn’t it?’ he offered, and she gave a slight, disbelieving laugh.

The last time she’d seen it, it had been dark, gloomy and had birds nesting in it.

Not any more. Now, it was...

‘Just a bit,’ she said weakly. ‘Wow.’

He watched her as she looked round the kitchen, her lips parted, her eyes wide. She was taking in every detail of the transformation, and he assessed her reaction, despising himself for caring what she thought and yet somehow, in some deep, dark place inside himself that he didn’t want to analyse, needing her approval.

Ridiculous. He didn’t need her approval for anything in his life. She’d given up the right to ask for that on the day she’d walked out, and he wasn’t giving it back to her now, tacitly or otherwise.

He shrugged off his coat and hung it over the back of a chair by the Aga, then picked up the kettle.

‘Tea?’

She dragged her eyes away from her cataloguing of the changes to the house and looked at him warily, nibbling her lip with even white teeth until he found himself longing to kiss away the tiny indentations she was leaving in its soft, pink plumpness—

‘If you don’t mind.’

But they’d already established that he did mind, in that tempestuous and savage exchange outside the gate, and he gave an uneven sigh and rammed a hand through his hair. It was wet with snow, dripping down his neck, and hers must be, too. Hating himself for that loss of temper and control, he got a tea towel out of the drawer and handed it to her, taking another one for himself.

‘Here,’ he said gruffly. ‘Your hair’s wet. Go and stand by the Aga and warm up.’

It wasn’t an apology, but it could have been an olive branch and she accepted it as that. They were stuck with each other, there was nothing either of them could do about it, and Josh was cold and scared and hungry. And the snow was dripping off her hair and running down her face.

She propped herself up on the front of the Aga, Josh on her hip, and towelled her hair with her free hand while she tried not to study him. ‘Tea would be lovely, please, and if you’ve got one Josh would probably like a biscuit.’

‘No problem. I think we could probably withstand a siege—my entire family are here for Christmas from tomorrow so the cupboards are groaning. It’s my first Christmas in the house and I offered to host it for my sins.’

‘I expect they’re looking forward to it. Your parents must be glad to have you close again.’

He gave a slightly bitter smile and turned away, giving her a perfect view of his broad shoulders as he got mugs out of a cupboard. ‘Needs must. My mother’s not well. She had a heart attack three years ago, and they gave her a by-pass at Easter.’

Ouch. She’d loved his mother, but his relationship with her had been a little rocky, although she’d never really been able to work out why. ‘I’m sorry to hear that. I didn’t know. I hope she’s OK now.’

‘She’s getting over it—and why would you know? Unless you’re keeping tabs on my family as well as me?’ he said, his voice deceptively mild as he turned to look at her with those penetrating dark eyes.

She stared at him, taken aback by that. ‘I’m not keeping tabs on you!’

‘But you knew I was living here. When I answered the intercom, you knew it was me. There was no hesitation.’

As if she wouldn’t have known his voice anywhere, she thought with a dull ache in her chest.

‘I didn’t know you’d moved in,’ she told him honestly. ‘That was just sheer luck under the circumstances, but the fact that you’d bought it was hardly a state secret. You were rescuing a listed house of historical importance on the verge of ruin, and people were talking about it. Bear in mind my husband was an estate agent.’

He frowned. That made sense. He contemplated saying something, but what? Sorry he’d died? Bit late to offer his condolences, and he hadn’t felt able to at the time. Because it felt inappropriate? Probably. Or just keeping his distance from her, desperately trying to keep her in that cupboard she’d just ripped the door off. And now, in front of the child, wasn’t the time to initiate that conversation.

So, after a pause in which he filled the kettle, he brought the subject back to the house. Safer, marginally, so long as he kept his memories under control.

‘I didn’t realise it had caused such a stir,’ he said casually.

‘Well, of course it did. It was on the at-risk register for years. I think everyone expected it to fall down before it was sold.’

‘It wasn’t that close. There wasn’t much wrong with it that money couldn’t solve, but the owner couldn’t afford to do anything other than repair the roof and he hadn’t wanted to sell it for development, so before he died he put a restrictive covenant on it to say it couldn’t be divided or turned into a hotel. And apparently nobody wants a house like this any more. Too costly to repair, too costly to run, too much red tape because of the listing—it goes on and on, and so it just sat here waiting while the executors tried to get the covenant lifted.’

‘And then you rescued it.’

Because he hadn’t been able to forget it. Or her.

‘Yeah, well, we all make mistakes sometimes,’ he muttered, and lifting the hob cover, he put the kettle on, getting another drift of her scent as he did so. He moved away, making a production of finding biscuits for Josh as he opened one cupboard after another, and she watched him thoughtfully.

We all make mistakes sometimes.

Really? He thought it was a mistake? Why? Because it had been a money-sink? Or because of all the memories—memories that were haunting her even now, standing here with him in the house where they’d fallen in love?

‘Well, mistake or not,’ she said softly, ‘I’m really glad you’re here, because otherwise we’d still be out there in the snow and it’s not letting up. And you’re right,’ she acknowledged. ‘It could have ended quite differently.’

He met her eyes then, his brows tugging briefly together in a frown. He’d only been back here a couple of days. And if he’d still been away—

‘Yes. It could. Look, we’ll see how it is tomorrow. If the wind drops and the snow eases off, I might be able to get you to your parents in the Range Rover, even if you can’t get your car there for now.’

She nodded. ‘Thank you. That would be great. And I really am sorry. I know I was a stroppy cow out there, but I was just scared and I wanted to get home.’

His mouth flickered in a brief smile. ‘Don’t worry about it. So—I take it you approve of what I’ve done in here?’ he asked to change the subject, and then wanted to kick himself. Finally engaging his brain on the task of finding some biscuits, he opened the door of the pantry cupboard and stared at the shelves while he had another go at himself for fishing for her approval.

‘Well, I do so far,’ she said to his back. ‘If this is representative of the rest of the house, you’ve done a lovely job of rescuing it.’

‘Thanks.’ He just stopped himself from offering her a guided tour, and grabbed a packet of amaretti biscuits and turned towards her. ‘Are these OK?’ he asked, and she nodded.

‘Lovely. Thank you. He really likes those.’

Josh pointed at them and squirmed to get down. ‘Biscuit,’ he said, eyeing Sebastian as if he didn’t quite trust him.

‘Say please,’ she prompted.

‘P’ees.’

She put him on the floor and took off his coat, tugging the cuffs as he pulled his arms out, but then instead of coming over to get a biscuit from him, he stood there next to her, one arm round her leg, watching Sebastian with those wary eyes.

He opened the packet, then held it out.

‘Here. Take them to Mummy, see if she wants one.’

He hesitated for a second then let go of her leg and took the packet, eyes wide, and ran back to her, tripping as he got there and scattering a few on the floor.

‘Oops—three second rule,’ she said with a grin that kicked him in the chest, and knelt down and gathered them up.

‘Here,’ he said, offering her a plate, and she put them on it and stood up with a rueful smile, just inches from him.

‘Sorry about that.’

He backed away to a safe distance. ‘Don’t worry about it. It was my fault, I didn’t think. He’s only little.’

‘Oh, he can do it. He’s just a bit overawed by it all.’

And on the verge of tears now, hiding his face in his mother’s legs and looking uncertain.

‘Hey, I reckon we’d better eat these up, don’t you, Josh?’ Sebastian said encouragingly, and he took one of the slightly chipped biscuits from the plate, then glanced at Georgia. ‘In case you’re wondering, the floor’s pristine. It was washed this morning.’

‘No pets?’

He shook his head. ‘No pets.’

‘I thought a dog by the fire was part of the dream?’ she said lightly, and then could have kicked herself, because his face shut down and he turned away.

‘I gave up dreaming nine years ago,’ he said flatly, and she let out a quiet sigh and gave Josh a biscuit.

‘Sorry. Forget I said that. I’m on autopilot. In fact, do you think I could borrow your landline? I should call my mother—but I can’t get a signal. She’ll be wondering where we are.’

‘Sure. There’s one there.’

She nodded, picked it up and turned away, and he glanced down at the child.

Their eyes met, and Josh studied him briefly before pointing at the biscuits. ‘More biscuit. And d’ink, Mummy.’

Georgia found a feeder cup and gave it to him to give Sebastian. ‘What do you say?’ she prompted from the other side of the kitchen.

‘P’ees.’

‘Good boy.’ Sebastian smiled at him as he took the cup, and the child smiled back shyly, making his heart squeeze.

Poor little tyke. He’d been expecting to go to his loving and welcoming grandparents, and he’d ended up with a grumpy recluse with a serious case of the sulks. Good job, Corder.

‘Here, let’s sit down,’ he said, and sat on the floor, handed Josh his plastic feeder cup, and they tucked into the biscuits while he tried not to eavesdrop on Georgie’s conversation.

* * *

She glanced over her shoulder, and saw Josh was on the floor with Sebastian. They seemed to be demolishing the entire plateful of biscuits, and she hid a smile.

He’d never eat all his supper, but frankly she didn’t care. The fact that Josh wasn’t still clinging to her leg was a minor miracle, and she let them get on with it while she soothed her mother.