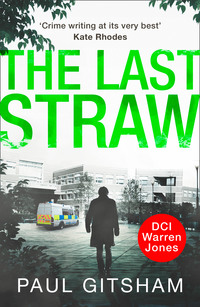

The Last Straw

A small window overlooked the car park below. Beneath it sat a small fridge, pulling double duty as a counter top. A mug tree jostled for space with four or five different jars of coffee, a jam jar of sugar and a box of PG Tips tea bags. The white plastic surface was ringed with brown stains from spilled drinks. Several dirty teaspoons were propped up in a coffee mug, itself in need of a good clean. Even by the standards of the CID tea room, the place was a health hazard. All three officers politely declined Crawley’s offer of a hot drink.

Motioning them to sit on the over-stuffed dentist’s chairs, Crawley flopped down himself. He looked physically exhausted, yet at the same time filled with nervous energy, Jones decided. Was it the weariness of grief? Worry about his job? Guilt? At this moment, Jones was keeping an open mind.

“First of all, Dr Crawley, could you tell us a little about yourself? I’m a bit mystified by the title ‘Experimental Officer’.”

“Basically, I’m the person in charge of running the lab on a day-to-day basis. The lab manager, if you will, except that I also do my own research. Alan…Professor Tunbridge…does…or rather did a lot of travelling and so I was the person in charge of making sure the lab ran smoothly in his absence. I’ve been with Alan for about twelve years or so, I guess.”

Jones nodded. “What can you tell me about Professor Tunbridge?”

Crawley sighed, took his glasses off and cleaned them, before placing them back again. The three police officers waited.

“Well, it’ll all come out in the end, I suppose… Alan was a brilliant researcher. His work was well respected around the world, hence his constant travelling. He has dozens of high-impact papers in all the best journals and regularly referees the papers of others in the field before their acceptance into journals.”

Jones sensed a “but”.

“But, on a personal level the guy was less than universally loved.”

Jones’ ears pricked up.

“Are you suggesting that the motive for his murder could be personal, rather than professional?”

“Look, all I’m saying is that, frankly, the bloke was a bit of an arsehole. He had a tendency to rub people up the wrong way, often for no good reason. He could really upset people and he just didn’t give a shit, ’scuse my French. He got away with a hell of a lot because of who he was and senior management used to excuse him ‘because he’s a genius and they can be funny sometimes’. Try telling that to a masters student in tears because her dissertation has been sent back with ‘crap — start again’ scrawled across it in red pen.” Crawley was clearly starting to unload years of pent-up frustration and Jones was willing to let him vent. Who knew what might come out…?

“The genius bit is bollocks. I’ve met a number of geniuses over the years and they were all nice blokes. Alan hadn’t got his Nobel yet, but he still acted like a wanker. At least three graduate students made complaints against him and two technicians claimed constructive dismissal. But Alan’s Teflon-coated. He usually got away with it.”

Crawley’s voice had started to rise and he broke off, breathing heavily.

“So why did you stay with him so long?” Jones asked.

Crawley sighed, the energy draining again.

“The sad fact is that despite all the nonsense, he was OK with me. I think he realised that he would be lucky to find someone else who’d put up with his behaviour. As for me, I’ve fallen with my bum in the butter. I can pursue my own research and I still get my name added to pretty much every paper that comes out of this lab.

“My problem is, I’m at the top of the research associate pay scale and my next career step is my own research group, but I’ve got a wife and three kids. The oldest will be off to uni next year, the youngest is still at primary school and has just been diagnosed with hyperactivity disorder and the family curse, dyslexia. My wife’s parents will probably have to go into a home in the next twelve months. I don’t have time to set up my own group, but I’m too expensive for anybody else to want me. Alan, for all his faults, was happy to keep on paying me. I guess we needed each other.” He gave a humourless grin. “If we were having this conversation in five years’ time, I’d say ‘cuff me now’, I’ve got every motive. I’d be ready to bump the old sod off and take over the group. But at the moment, it’s the last bloody thing I need.”

Jones nodded, not yet convinced. He moved on to another tack.

“Who else could have a motive for killing Tunbridge?”

“It’d be easier to ask who didn’t. Frankly he pissed off most people that he met. Plenty of collaborators over the years have complained that he was dictatorial and manipulative. He put plenty of noses out of joint by taking advantage of other people’s research, but the simple fact is that there is one rule for us and one rule for people like him. But that was mostly professional jealousy. I can’t see any of these guys killing him over who deserves to be first name on a paper in the Journal of Bacteriology.”

“OK. Leaving aside professional rivalries, what about closer to home?”

“Well, he was a philandering bastard. He shagged at least one of his undergraduate students, not to mention a few colleagues that he used to meet at conferences. For somebody with such an unpleasant streak, he never seemed to have any problems getting laid.”

“Can you give me any names?”

Crawley thought for a moment, his brow creased in concentration.

“I think one of them was called Claire or something. Rumour mill has it that she was one of the students on his Microbial Genetics course and he took a shine to her. There were the usual claims that he gave away good grades in exchange for sexual favours, but that’s bullshit. I know for a fact that undergraduate essays are all marked independently and anonymously from the tutor that sets them to stop that sort of stuff happening. Anyhow, she moved on and we haven’t heard from her since. This was some months ago.”

Jones noted down the details, deciding to pursue the lead nevertheless.

“I guess the people with the biggest grudge against Alan would be his former grad students and postdocs. He treated some of them shockingly. I know, because I usually ended up picking up the pieces.”

“Anyone in particular?”

“Well, I suppose Antonio Severino is the first name to spring to mind. He was one of Alan’s postdocs until recently, then things went horribly sour.”

“How? By the way, could you just clear up some terminology for me? What is a ‘postdoc’?”

“Well, a postdoctoral research assistant or associate is a junior researcher at a university. Basically, you do your PhD, to become ‘Doctor’ and then do a couple of research positions of a couple of years apiece in other people’s laboratories to gain experience. In some countries, such as Canada, you are still regarded as little more than a glorified student. Fortunately in the UK it’s now a properly salaried position with all the usual benefits.

“Anyhow, Dr Antonio Severino joined us about two years ago. He’s a smart guy and managed to solve a couple of really difficult problems that we were struggling with. Anyway, Alan being Alan felt a bit threatened by this as he realised that Antonio was inevitably going to share a lot of the limelight when the research was published and so he announced out of the blue that when Antonio’s initial appointment expired in six weeks’ time, he wasn’t going to renew the post. Furthermore, he was going to hold off on the publication of several key papers until he had some more data. This really upset Antonio. You see, not only was he out of a job in six weeks, he is also not going to have any publications to show for the past two years. In this climate he’ll be lucky if he gets a job cleaning glassware. The long and the short of it is that Alan absolutely shafted the poor bastard.”

“How did Dr Severino take this?”

“How do you think? Not to be stereotypical, but Antonio is a full-blooded Italian. They had the mother of all shouting matches in the lab, which spilled out into the corridor. Half the building must have seen and heard it. Anyway, I finally persuaded Antonio to leave and go home for the day, promising I’d talk to Alan about the papers. Antonio did calm down enough to leave the building, but he went straight down to the pub.

“He’s always been a drinker, but that day he excelled himself. According to a couple of Mick Robinson’s group who were having lunch in there he got absolutely wasted. When they arrived he was already really pissed, drinking shots. They knew him and everyone sympathises with you when you’re dissing the boss, so they sat with him for a bit. Eventually they figured he’d had enough and called him a cab.

“Apparently, he did get in the cab, but changed his mind halfway home and got the driver to drop him off outside here. I guess he was going to come back in and have it out with Alan again, but he got distracted by Alan’s rather nice shiny BMW and used his penknife to slash all four tyres and his house keys to scratch some sort of Italian obscenity on the bonnet. Did about three grand worth of damage, I’m told, before one of the security guards stopped him.”

Crawley’s expression hinted that he might not have been entirely disapproving of his co-worker’s actions. “Well, Alan was all up for doing him for criminal damage, but the University Disciplinary Committee decided that it wasn’t going to do anybody’s reputation any good if this got into papers, so as usual I did my best to pour oil on troubled waters.

“In the end, I persuaded the university to let Antonio see out his last six weeks on gardening leave. Alan agreed to let me write him a decent job reference, which he signed and put ‘papers pending’ on the references list on his CV. Antonio consented to pay the excess on Alan’s insurance claim. I tell you guys, some days I feel like the Secretary General of the United Nations in this place.”

“How long ago was this?”

“About four or five weeks ago.”

“And has Dr Severino had any luck in finding another job yet?”

“I had a request to pass on his references a couple of weeks ago to a lab at Leicester Uni. I haven’t heard anything back from Antonio, so I’d guess he’s probably been unsuccessful.”

Jones nodded, taking note. Severino certainly had a big enough motive and if he had just been turned down for a job that could have been a trigger.

“Tell us about Dr Spencer.”

“Tom? Oh, he’s not doctor yet. He’s a final year PhD student.”

Karen Hardwick half raised her hand almost as if she were at school. However, her voice was firm and betrayed none of the nervousness she was feeling at interrupting her superiors.

“What stage was his PhD at? Was he still working or writing up?”

A brief look of discomfort passed across Crawley’s face.

“He was writing up, although he was still doing a few experiments to tidy things up.”

“What stage was his thesis at? Was he still in his third year or was he in his write-up year?”

Jones listened carefully. He had no idea where Karen’s line of questioning was going, but the vibes he was getting off Crawley suggested that he wasn’t thrilled about the direction. That alone made the questions worth asking in Jones’ book.

“He was in his write-up year. He’d submitted some draft chapters to Alan for editing.”

“It’s August now. Assuming he started in September, he must be pretty close to the end of his fourth year. Would that be correct? How was he funded and is it still current?”

“I’m not sure why this is relevant.”

“Please, bear with me, Dr Crawley.” DC Hardwick’s eyes didn’t leave the increasingly uncomfortable-looking scientist.

“Yes, he is within a couple of months or so of the end of his fourth year. He was funded by the Medical Research Council. The funding will have ended by now.”

“How much of his thesis had Professor Tunbridge approved? Is Mr Spencer on course to finish within the four-year deadline?”

“I wouldn’t know about that.” The lie was weak, but Hardwick decided not to pursue it.

Sutton now picked up the gauntlet. “How would you characterise the relationship between Mr Spencer and Professor Tunbridge?”

“Well, Alan was a difficult man, as I think you are realising, and the relationship between students and supervisors is often tense, but I never saw them have a stand-up row like he did with Antonio Severino.”

Jones looked at his colleagues; they seemed to be content for the time being. He looked forward to their thoughts. It was clear that Crawley wasn’t telling the whole truth, but he was unsure how to proceed just yet.

“Well, thank you for your time, Dr Crawley. If you could give one of my colleagues your contact details that would be very helpful. I would also appreciate the names and contact details of other members of the research group. We may call you again in due course with some more questions. In the meantime, I believe that we have an appointment with the head of department, Professor Gordon Tompkinson.”

Jones stood up, signalling the end of the interview. Crawley looked relieved.

“Let me take you to see Professor Tompkinson.”

As they exited the small room Jones spotted the young uniformed constable, standing outside the taped-off entrance to Tunbridge’s office. Beckoning him over, he instructed him to take down the details that he had requested from Crawley when he returned from taking them to see Prof Tompkinson. That should give him something to do besides read the newspaper, Jones thought.

Just then another uniformed constable appeared.

“Sir, the head of Security has just arrived. He is ready to go through the CCTV and the building’s access logs.”

“Thank you, Constable.” Jones turned to Sutton. “Tony, can you go and see what they’ve got? The sooner we can start corroborating some alibis, the better.”

“Will do, guv.” He turned smartly on his heel and strode off after the already departing constable.

* * *

“Dr Crawley, Mr Spencer claims to have been working in something called the ‘PCR room’ when the murder is believed to have taken place.”

“He’ll have meant Molecular Biology Suite One, on the ground floor. Do you want to go there?”

“Yes, please, if you wouldn’t mind.”

Motioning them to follow, Crawley headed back towards the front of the building. Taking them back down the stairwell that they had used earlier, he then doubled back on himself, so that they were heading back into the building again. To their left were more offices and Crawley motioned to a set of double doors.

“That’s the main admin office where the head of department, Gordon Tompkinson works. I’ll bring you back here after I’ve shown you the PCR room. I saw his car in the car park by the way, so he is in.”

They continued down the corridor past yet more offices on the left. Through an open door Jones caught a quick glimpse of another tea room, this one a little tidier, again overlooking the car park. The rooms on the right appeared to be service rooms rather than laboratories, with signs on their doors such as ‘Sterilisation Unit’, ‘Media Kitchen’ and ‘Central Stores’. All the doors were shut but windows with old-fashioned wire-mesh safety glass afforded glimpses of darkened rooms beyond. The air was humid yet at the same time smelled musty. Jones made a note to ask Karen about it later, again reminded that in this environment he really was a fish out of water. Finally they pulled up outside another set of double doors. Unlike the others in the corridor, there was no glass window to hint at what went on inside. The sign, ‘Molecular Biology Suite One’ meant nothing to Jones. These doors seemed sturdier and to the right of them was another swipe-card reader.

Crawley paused outside and motioned to the reader with the card that he wore on a lanyard around his neck. Jones thought for a moment - would entering the room compromise a crime scene? No, he decided, it was clearly a communal facility and besides which Spencer had been wearing latex gloves and other sterile clothing. It was unlikely that Forensics would get much in the way of useful trace evidence in there.

“Please, go ahead.”

Crawley swiped the card and there was the quiet click of a magnetic lock. A green LED lit up on the card reader. Pushing the door open seemed to require some effort and Jones felt a blast of cold air.

“Positive air pressure,” explained Crawley without being asked. “It helps stop dust and other contaminants getting in and damaging the equipment. There is also air conditioning to keep everything at a constant temperature and humidity. They look after the equipment better than they look after the staff,” he quipped weakly.

Stepping in, Crawley reached and flicked on the lights. Jones and Hardwick followed him in. Jones was immediately glad of his suit jacket. The air temperature was a few degrees too cool for his comfort and a marked contrast to the warm August weather outside.

The room was like something out of a science-fiction movie, he decided. A reasonable size, it was nevertheless crammed with benches full of equipment. The three of them were able to fit into the room side by side, but to accommodate anybody else someone would need to shuffle along one of the other aisles. The doorway in which they stood was the only entrance and there were no windows. Over the rush of the air conditioning, Jones noticed a sound that reminded him of the Scalextric racing car set that he’d had as a child. A sudden, high-pitched whine, followed by silence, then repeated again, as if he were accelerating the tiny cars along the track, stopping them, then starting again.

“Welcome to Molecular Biology Suite One, the jewel in the crown of the Biology department.” Crawley swept his hand, in a wide arc. “There’s the better part of two million quid’s worth of equipment in here, or at least that’s how much we paid for it when it was new. It’s also the most secure room in the building, not including the animal house.” He gestured upwards with a nod of his head, no doubt a reference to the unlabelled fourth floor that didn’t exist on the building’s public plans but which Jones had read up on when familiarising himself with potential terrorist targets.

It was certainly impressive, he decided. Pride of place was a large glass-fronted unit, the size of a commercial chest freezer, with ‘Affymetrix’ emblazoned across it in blue. Jones hadn’t got the faintest idea what the machine did, but it seemed to be filled with stacks of plastic trays. This, he realised, was the source of the noise. He watched fascinated as a robotic arm scooted, whining, across the length of the machine, delicately picked the top tray off a stack, before moving it to a different stack to its right. From above, a second arm appeared, this time bristling with dozens of metal prongs, which it inserted into some of the hundreds of tiny wells that Jones now saw made up the tray. Removing the prongs, the arm moved rapidly, but precisely, to the right, before lowering the prongs slowly onto what appeared to be a frosted-glass microscope slide.

Noticing Jones’ interest, Crawley gestured towards the machine.

“It’s a slide maker for gene expression studies — it’s the reason for the security. It, and the equipment to read the slides, is worth hundreds of thousands. The university’s insurers insisted that we put it behind locked doors in case it gets stolen. There is a growing black market for these things in the Biology departments of developing countries. It’s also incredibly delicate, hence the air conditioning.”

“Is this what Tom Spencer was using Friday night?”

“Oh, no. This is strictly the property of the gene expression laboratory. Tom was probably using the Tetrad PCR machine. It’s not in the same league as the slide maker, but it’d still be worth nicking if you had a buyer for it.”

Crawley led them down a side aisle to a squat black bench-top machine about the size of an old-style desktop computer sitting on its side. The equipment had four hinged lids, all closed, with electric-blue screws on top. A large keypad on the front was flanked by an LCD screen to the left and a stylised DNA molecule as a logo to the right. The machine seemed to be switched off. What appeared to be a booking sheet was covered in scribbled names. ‘Tom Spencer, Friday p.m.’ was scrawled under a column headed ‘Block One’. The other three blocks were empty at that time. Judging by the number of different names listed on the booking sheet, this seemed to be a popular machine. Even if Spencer wasn’t wearing gloves when he used it, Jones doubted that they would find any useful trace evidence.

Motioning back toward the room’s only entrance, Jones asked how to exit the room.

“There’s another swipe card. Security keeps a log of everyone who enters or leaves the room.”

“What if you prop the door open? How do you get out if your swipe card isn’t working?”

“If you prop the door open, after about a minute an alarm sounds. Similarly, if for some reason you manage to swipe yourself in but can’t get out, you can press that green fire-alarm-style button to release the lock. That also triggers an alarm. Either way, Security come running and you get a serious bollocking.”

So it looked as though once you swiped in, you were in there until you swiped out again. With no more questions, Crawley led them back out into the warmth of the corridor. Jones removed his mobile phone from his suit jacket. Sutton answered within two rings.

“Tony, it’s Jones. Have you had any luck with the head of Security yet?”

“Just getting there, guv. We’re looking at the CCTV as we speak.”

“Good. Can you also see if you can obtain a printout for the day’s swipe-card access logs for the building’s main entrance and for Molecular Biology Suite One?”

Jones heard his request being relayed in a muffled voice, followed by a short reply, too indistinct to understand. “Shouldn’t be a problem, guv. I’ll call as soon as we have anything, Sutton out.”

Jones smiled slightly. Using mobile phones instead of radios was still a bit strange to older members of the force and so they had a tendency to resort to radio-speak when using them at work. Jones was no different. Susan had teased him for weeks after he had phoned her from the fish and chip shop one evening and ended the conversation with ‘over’.

That reminded him, he’d better call Susan when he had a few minutes. She was fairly understanding about his work commitments, but insisted that she should at least be given a rough idea of when he would be home. Quite how understanding she would be today was another question. One of the reasons for her parents’ visit was to celebrate Bernice’s birthday. The plan was for Susan and Warren to take Bernice and Dennis into Cambridge for an early dinner, followed by a play at the Corn Exchange. Warren prayed that he didn’t have to skip that, for then he would really be in the doghouse. As understanding as Susan was, an evening of frosty silence from her mother would not leave her in a good mood. Warren just hoped that the previous night’s red wine had been good enough to temper Bernice’s displeasure at his sudden departure.

With at least a couple of his questions answered, Jones suggested Crawley take them down to see the head of department. They were led back down the corridor in a thoughtful silence. Jones stared at the back of Crawley’s head, his mind whirring. He’d started the day with only one potential suspect. Now it would seem that there may be dozens of people with motives. He glanced over at Hardwick. Her brow was furrowed and she was clearly thinking hard. Jones looked forward to her thoughts. One question in particular troubled Jones.

Why was the professor in his office at ten p.m. on a Friday? And how had his killer known?

Chapter 4

The head of department’s office was on the ground floor, close to the main reception area where the three officers had entered earlier. The entrance to the head’s office was actually inside a larger office complex signed as ‘Department of Biology — Administration’. A long, narrow room, it occupied almost an entire side of the building and was filled with a half-dozen workstations. Each desk had a comfortable-looking office chair, a desktop PC, a telephone and in and out trays, some empty, others stuffed with paper. A bank of cryptically labelled filing cabinets lined the wall underneath a row of windows overlooking the car park. A large photocopier and an industrial-sized paper shredder filled the remaining gaps along the wall. Two laser printers sat on top of the filing cabinets, along with a box of white A4 photocopy paper. The empty room smelt of stale coffee and ozone from the photocopier. The office seemed representative of the building as a whole, decided Jones. Nineteen-sixties architecture, a couple of decades past its prime, struggling to do its job in a world that bore little resemblance to what the planners had envisioned.