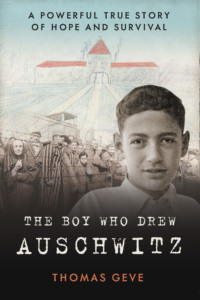

The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz

Equipped with sticks, we advanced in a military-style formation towards the tall brick wall, the spot where the kitchen refuse was deposited. A ragged olive-green uniform bent itself up from the smelly, rotting heap. It contained a human being. His unshaven head was covered by a forage cap, his bare feet housed in wooden clogs. A mouldy turnip was gripped tightly in his shaking hands.

In response to our barked commands, he hastily turned back to the shelter of the refuse pile from where he had come. Suddenly one of our group shouted, ‘Look at his back; there’s a big black SU printed on it. What does that mean?’

‘Yes, it means the Soviet Union,’ we were told by a bright boy, known for being able to distinguish between all the latest makes of cars and aeroplanes. ‘It’s the place where the sub-humans come from.’

But Russia was an ally of the British against Hitler, so we decided to call the rummager back for a more friendly interrogation.

With the aid of a hurriedly summoned work colleague who knew some basic Polish we somewhat hesitatingly accepted this intruder’s explanation. He was a Russian soldier. In broken English, he explained as much as he could.

‘Soldier kaput – he work hard, eat little – he escapes – escaped Russians shot – German bad – Jew friend – he not eaten in two days – he hungry.’

We could quite imagine this robust figure, his uniform shining in all of its old glory, marching on parade somewhere in far-off Russia and about to enter the battlefield against our common foe. The soldier deserved our sympathy. He ate raw turnips and we fetched him some more. We wished him good luck and then he scurried away.

Our desperate circumstances could not change the fact that I was a boy. And it was Eva-Ruth, the girl I worked and lived with, who first aroused my interest in sex.

A buxom, strawberry-blonde lass of 14, she took a liking to me. ‘Don’t come in now,’ she would cry, ‘I am only dressed in my kimono. There is only me and you in the flat, so don’t be nasty.’

After a few minutes, she would continue flirting with me by announcing that she was only scantily clothed. I would naïvely continue to wait outside her room. Too young to understand her hints, my sole reward was her rebukes for my clumsiness. We teased each other and lay on the same sofa side by side, but could not make ourselves go any further.

The more I adored her body, the more I hated her mind. Her arrogance and prejudices were foul. Liking workmates of a non-German heritage was below her dignity. Occasionally, when I was the object of her heated quarrels, even I would be denounced as a ‘dirty Eastern Jew’.

Her education, like that of many a German Jew, had been one of ‘Deutschland über alles’ (‘Germany above all’). Conforming to the accepted social pattern was all that mattered to Eva-Ruth. An educated person’s superior attitude may have suited more secure and comfortable surroundings, but now it was hopelessly out of place. The orderly German way of life was collapsing. There was no point in clinging to its memories.

One Sunday afternoon in June 1943, a guest arrived at Eva-Ruth’s place for tea. He was a friendly character, smartly dressed, and he politely made himself at home.

This mysterious gentleman told us that he was a Jew who had been recruited by the Gestapo to seek out candidates for deportation. Strangely, he gave no reason why the Gestapo had persuaded him to do this traitorous task. He told Lotte that the few remaining Jews in Berlin had become more elusive and did not merit any large-scale action from the Gestapo. So a new scheme had been decided upon, ‘arrests by persuasion’, to be carried out by Jews like himself over a cup of tea.

Having come down with influenza, I had not been to the cemetery for a few days. I then heard through our seductive but treacherous visitor of a round-up that had been carried out there. Only a few workmates managed to escape via the cemetery’s back gate.

Eva-Ruth and Lotte’s arrest orders already lay on the table. My name was not on the visitor’s pencil-marked list, but he assured us that it soon would be. A final rounding up of the few remaining Jews and half-Jews in Berlin, whether they were in hiding or not, had already been decided upon. ‘To come voluntarily would be better than facing nerve-racking days, waiting for the inevitable knock on the door,’ he said.

Not convinced, we decided to let events take their turn.

Lotte and her daughter, Eva-Ruth, were arrested soon after. Mother and I spent two more days in the deserted flat pondering our future.

We deliberated on our increasingly desperate situation. It seemed that the war would continue for many more years, and we could not find a reliable hiding place. Our resources and possessions could barely finance a month’s illegal living. The terrifying realisation that our options were reduced to nothing meant that we had to make a decision. I reasoned that I was used to hard work and that the Eastern working camps that we had heard about might not be that bad. A good worker might even make a fair living. Finally, there was the insatiable hope that I might effect another release for me and Mother. We decided to hand ourselves in.

Once again, we set out across Berlin weighted with the inevitable four suitcases. Three months before on that street corner in north Berlin, we had taken off our yellow Stars of David. We now had to reattach them. Hungry, exhausted and scared, we re-entered the Grosse Hamburger Strasse detention centre.

This time around, there were different types of inmates packed into the transit camp – the last of its kind in Berlin. The motley but high-spirited prison crowd was made up of half-Jews, caught ‘illegals’, foreigners, community workers and the elderly. Jammed in though we were, a dozen to a room, with food and water mostly nonexistent, somehow an atmosphere of defiant hope prevailed.

A group of young Zionists had arrived from a German farm that had been turned into a prison. Every evening they organised discussion groups, sang sentimental tunes and even danced the Horah.3 Where their enthusiasm sprang from was beyond me; so was the technique of their happy dancing steps.

Eva-Ruth, too, had finally found her mate there. He was someone less naïve than me, and to the general disgust of the camp, she had gone to live in his cell. I was jealous and felt lost.

The few Polish Jews who escaped from the so-called ‘concentration camps’ attracted everyone’s compassion. These Easterners told their stories with such repetitious fervour that only a few of us thought that they were exaggerating.

One man stood out from the crowd. A depressed, nervous and pitiful young man who claimed to have fled from a camp called ‘Auschwitz’. This was one of the supposed Silesian working camps. His constant fidgeting and lack of self-control when talking made his accounts difficult to comprehend. From what little we could gather, they were also far-fetched. He deliriously shouted about the horrors of Western civilisation, offering no proof in the process. We had never heard of Auschwitz. Our shredded nerves about what lay ahead of us were already stretched far enough, which only added to our anger towards him.

Sorting out for the impending transports had started in earnest. Old people and owners of war medals would be sent to Theresienstadt, the rest to the East. Where? We did not know. Lectures on how to behave during the journey were followed by the distribution of identification numbers and basic rations. Next morning, we mounted the lorries that took us to Berlin’s Stettiner Bahnhof goods station.

Mother and I, doing our best to keep together, were hustled into a wagon alongside twenty or so fellow passengers. Mother had told me to bring my winter coat as it would get cold in the East. We left Berlin in one of a dozen closed wagons waiting for departure.4

Laid out with straw, our wagon had four small barricaded ventilation slits, no windows and a solitary sanitation bucket that was to be shared by all of us on our journey to the East. We did our best to find some space in among each other and all the suitcases. My eager eyes had just about managed to catch sight of an inscription that was left over from our carriage’s pre-war days in France. I asked one of my neighbours to translate the sign that was nailed to the inside of our wagon. It stated: ‘40 soldiers or 8 horses’.5 At least we had a semblance of room in our wagon.

Then the train pulled out. As a defiant gesture towards their native Berlin, the worried souls in our carriage, which were all of us, summoned the energy to sing a final tune of farewell. Tall factory chimneys, signposts to the city’s eastern suburbs, silhouetted against the falling dusk, receded along either side of the track as we made our last journey out of the city. There was an eerie silence as we pulled out, the blackout seemingly unable to sense her last few departing children. In that cramped, smelly carriage, who could say how many of us would ever see Berlin again? Perhaps now she was ashamed of herself and our plight?

As we rolled away from Germany, the regular rhythm of the wheels counting off rail by rail lulled us into uncomfortable thoughts. We were leaving a world that was lost for us – the very world that had lost itself.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов