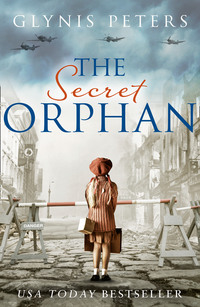

The Secret Orphan

Rose looked to her daughter who shrugged her shoulders. ‘I think it was a compliment,’ she said, and Rose laughed.

Once everyone had left her apartment with promises to call and visit, Rose kicked off her shoes and placed her brooch into its box. She slipped off her dress and wrapped herself in the new fleece dressing gown, a gift from her daughter. She fetched her reading glasses and read the simple picture by picture instructions on how to use the new coffee machine – a gift from her sons – and after following each one, she eventually poured the contents of the jug into a new mug that shouted out to the world she was the best grandmother. Sitting on her favourite chair, Rose settled down for the evening. She flicked on the TV from the remote control and selected a programme about purchasing a new home. It was an imported programme from the UK. Rose loved to step inside with the presenter and listen to couples deciding whether to purchase or keep looking. Some enjoyed browsing properties abroad, making the bold step to leave all they knew behind.

Rose sipped her decaffeinated coffee and nodded her approval when one couple opted to buy a property on the coast of Cornwall. With a sigh, Rose set down her empty mug, sat back and watched the credits role as the programme came to an end. She leaned back in her chair, yawned and allowed her eyes to droop into a semi-sleep as she recalled the day they’d all left England.

The sounds rattled over her head. The large ship sitting in dock blew its horn and people shouted to one another from ship to shore. Elenor had guided her one way and then another. Jackson had hailed a porter and offloaded their bags. Rose knew they wouldn’t lose their luggage because she’d been given the important task of writing their names and new address on the labels Jackson had given her. She’d used her best handwriting and when it came to writing Canada, British Columbia, she took extra care creating neat capital C’s.

Her new father had looked over her shoulder and gave it an affectionate tap the afternoon she wrote out each label. His praise still made her smile.

‘My word, well done little Rose. Those letters are sure proud and round.’

Her new mother gave her a hug.

‘She’s a clever little button, and this mummy is extremely proud of her.’

Once the porter had loaded all labelled suitcases onto his trolley and headed towards the ship, her father had lifted her high onto his shoulders. The view was incredible. Everyone looked like ants scurrying about their business.

‘I can see for miles! There’s hundreds of children. Do you think they will play with me?’

‘I’m sure they won’t want to play with a little scallywag like you,’ her father had teased, earning himself a tug of the ears.

They came to a standstill near the entrance to the ship. Her father had explained the gangway might sway as they walked up it to the ship’s deck, but that they were perfectly safe.

‘I’ll take you to a suspension bridge in Vancouver, the gangway will give you a sense of what to expect. Now stand here my little Rose while I give your mom some last minute instructions.’

Rose knew he meant kissing. They’d done a lot of that since their wedding day. She stood patiently and looked around at other couples embracing loved ones. Soldiers, sailors, airmen, women in uniform, women in everyday dress, and women in fine outfits were all squashed together in the crowd. Class separated no one when it came to saying farewell.

She took hold of her mother’s hand and received a warm smile.

‘Elenor. I’m scared,’ she said.

‘Afraid? We’ll be fine. What an adventure. Canada, here we come. We will be all right, you know. Besides, we have Jackson for good luck.’

Rose nodded, and she looked to the man who gave her his love unreservedly, who made her laugh and made it easy for her to love another father. He reached out and tucked one of the little blonde curls of hair struggling to break free back into place behind Rose’s ear.

‘It will be fine, honey. I’ll be with you all the way. Isn’t it a big ship? I wonder which cabin will be ours.’

As the ship left shore with her horns blowing, Rose’s legs trembled, and her bladder threatened to let her down. She knew life would never be the same again. She stood between her new parents and knew whatever their reasons for leaving Tre Lodhen and moving to Lynn Valley, they were the right ones.

Chapter 3

August 1938: Cornwall, England

Elenor traced her finger across the label attached to the side of her battered suitcase.

Miss Elenor Cardew.

Care of: Mrs M. Matthews,

Stevenson Road

Coventry.

As the bus trundled noisily out of the village and headed for Plymouth, Elenor thought back to when the telegram requesting her help – well, more a command to do as she was told – was placed before her when she sat down for supper.

‘This came. You’d best pack and be ready to leave when the bus arrives tomorrow. You must collect your train ticket.’

Her eldest brother spoke in his usual gruff, stilted tone. At eighteen, Elenor was ten years younger than her brother James, and there was never a kind word spoken, or a soft expression of love for his youngest sibling.

‘Train ticket, James?’ Elenor said.

‘Read it. I’m eating.’

Elenor pulled out the thick white paper and read her aunt’s neat handwriting, which gave strict instructions of the date and time she was to arrive in Coventry. It also informed her a one-way train ticket would be waiting for her at Plymouth station, along with instructions of changes to be made along the way.

‘We’re both in agreement. It has to be done.’

Elenor looked to her other brother, Walter; he too spoke in a dull tone with no kindness. The twins resented her birth, and both treated her with no respect.

‘You’re both in agreement? And I have no say. Aunt Maude is a tyrant. A bore. Why me?’

She flapped the letter high in the air.

‘No dramatics. Just do as you are told.’

‘Oh yes, James. And who will run this place? You?’

‘We’ll manage.’ James replied.

‘But what about harvest? You need all hands available for harvest time.’

‘The matter is closed. Do as you are told,’ Walter said and bashed his hand on the table.

With the thought of not breaking her back gathering in the hay, and chafed hands not giving her problems, Elenor suppressed a smile. In an attempt to continue her pretence of hardship, she pushed back her chair and flounced from the room, calling over her shoulder as she stomped her way upstairs.

‘I’ll leave you to wash your dishes while I go pack. You’d best get used to the extra chores, idiot.’

‘Enough of your insults, get back here!’

Elenor ignored her brother, he really was an idiot, and slammed shut her bedroom door. What was the worst he could do? He had no intention of keeping her on the farm. She’d be as dramatic as she wanted.

She read the letter again. Not thrilled about caring for her aunt, Elenor was nonetheless excited about leaving Tre Lodhen – not the farm itself, but the life she endured within its boundaries. She loved her home and would miss the Cornish countryside, but she would not miss her brothers and their cold manner towards her. Coventry offered a smidgen of excitement for a young woman wanting more from life. The village of Summercourt did not excite her, it only held her back. A mantra she’d repeat for anyone who cared to listen. Amateur dramatics in the village hall kept her from dying of boredom, and on the rare occasion she made her escape to a village event, Elenor loved nothing more than to sing, but it had been months since her brothers had allowed her time away from her chores.

The creative Elenor was suppressed at every opportunity. There was no shoulder for her to cry on or a listening ear when she needed to vent her frustrations.

On the day her mother died, Elenor’s role became obvious: she was to step into her shoes. And she did, quite literally at times. Their Aunt Maude would send a few pounds to help her family through hardship if the farm failed to produce a good crop, but it never went far and more often than not to the London Inn, their village pub. When her mother died so did any love Elenor had ever experienced. Her father had the same attitude as her brothers. He’d worked her mother to death and Elenor was made to pick up the pieces. The males in her life never gave any thought to Elenor’s needs, she never saw a penny of the money sent or earned. When it came to her birthday, she soon learnt there would be no gift and accepted it as a normal working day. The ingratitude from her family over the gifts she offered them in the past meant she no longer bothered. Christmas also came and went with the only difference being her father and brothers spent a few extra hours and coins enjoying the company of the London Inn landlord.

No amount of moaning about always having to make do with what she found in the farmhouse ever gained Elenor new clothes. Scraps of cloth filled out shoes too large and repaired handed down dungarees from her brothers. When their father died four years after her mother, the twins did nothing to change Elenor’s life. Neither showed any signs of marrying. There was no other woman in her life to help with the domestic tasks. She had no escape from the humdrum of daily life. The Depression meant nothing but hardship to Elenor, so this opportunity to enjoy a different style of living appealed to a girl of her age.

With no available money and the realisation that her farm clothes were not suitable, she spent her evening altering two of her mother’s old dresses. She’d kept them in a trunk in readiness for when they’d fit her properly. Their drab brown and greens did nothing to flatter her tanned complexion.

She imagined her aunt Maude’s stern tut-tut when she saw the brown leather belt holding her battered suitcase together. The pathetic contents would also send her into a frenzy of tutting, a sound Elenor had heard leave her aunt’s lips many times in the past. Her mother’s eldest sister was a force to be reckoned with when it came to snobbery – her father’s words, not Elenor’s. In the past the woman had scared her with her black gowns and upper-class manner, but Elenor would never dare breathe a word against the woman. When her aunt had visited the farm to nurse her sister, she’d taught Elenor a few basic rules of grace and how to conduct herself in a better manner than some of the female farmhands. Elenor often hoped her aunt would become her key to freedom, and today, in a roundabout way, she had become just that.

The following morning the bus bumped its way past fields of cattle chewing the cud in a leisurely manner. It jostled over cobbles and through narrow winding streets past small stone cottages. Clusters of women stood passing the time of day with village gossip, and men gathered around a cow on a piece of ground close to the inn. Elenor knew they’d haggle for a good price until opening time when half would be spent inside the inn sealing the deal. There was no hurry or urgency in their tasks. Slow-paced and content, the villagers laughed and frowned together. Elenor envied their ability to accept their lives. Even though she felt stifled in Summercourt, under different circumstances she might have found living there more bearable.

When the slate roof and granite walls belonging to the Methodist church came into view, Elenor shivered. The last time she’d entered those doors was to lay her father to rest. It had been a sombre affair and her brothers had been particularly obnoxious that day. Her father’s will had stated the farm be left to all three children, but the boys insisted it meant male heirs, and took no notice of her request for a wage. They stated Elenor was holding onto her part of the farm by living there rent-free.

Elenor continued to stare out of the murky glass and focused upon the trees as the bus meandered towards the edge of the village. She envied the power of the oak as it stood fast against the wind blowing in from Newquay, and she was fascinated by the way the silver birch dipped and swayed much like a group of dancers together in rhythm, with elegance and poise. They reminded her of the male versus female challenges she’d encountered over the years. One standing strong and the other bending to the will of another.

‘Clear your head, Elenor. Think pleasant thoughts.’ She muttered the words as she refocused on children playing with a kitten. Their giggles brought a smile to her face and reminded her of when she and her mother had chased three tiny farm kittens who’d found their way into the house. They’d had such fun chasing them back out into the yard.

The bus driver slowed down for a few sheep and Elenor could see Walter lumbering along in front guiding them into a new pasture. He was identifiable by his long greasy hair flapping like bird wings in the wind.

Resentment choked her. Neither of the twins had seen her off that morning. Not one had said goodbye.

Wait ’til you get home to a cold house and no meal. You’ll regret your haste to be rid of me so easily. Oh, and I’ve left you a parting gift in the sink after the way you treated me this morning!

Both men had risen at sunrise and ate the breakfast she had prepared, then left without a goodbye. Elenor looked around but could see no sign of a coin left out for her journey.

With a heavy heart she packed food, a bottle of water and a tin mug into a cloth bag.

She was so angry with her siblings she threw the dishes into the sink. She heard the chink and ping as they crashed against each other.

‘You can do your own dishes. When you’ve repaired them.’

She’d shouted the words to an absent audience.

Tears fell as she’d gathered her bags and walked away. Now, watching her brother she felt nothing.

‘Goodbye village. Sadly, I won’t be back this way again,’ Elenor whispered.

Chapter 4

A weary Elenor forced her tired legs the last few yards to her aunt’s home. Coventry city bustled around her. She jumped at buzzing noises from the car manufacturers and inhaled the delicious aroma from a bakery. It taunted her grumbling stomach. Eight hours and counting since she ate her last meagre meal.

Her suitcase bumped against her legs as she hurried along the narrow, cobbled streets. Despite her initial excitement about leaving Cornwall, the grey of the city streets closed in around her and gave Elenor a new set of anxieties. Had she been wise in leaving the farm? Maybe she should have fought harder to stay. At least when the men were at work she was left alone in peace and silence. Would that be the case here?

As the road shortened and her aunt’s home came into view, it wasn’t just the case weighing her down. Elenor trudged the last few steps trying to ignore the blisters on her feet, and once she’d arrived at the house she stood back to look at her surroundings. The house was smaller than she remembered. Smaller than the farmhouse, but larger than the terraced houses running either side of the street, the detached house sat as if at the head of the table, relishing in its glory of being the only one, yet to Elenor it lacked beauty. The house was a testament to her aunt’s snobbery. It was too symmetrical, too neat, square with bay windows either side – unlike the higgledy-piggledy medieval properties she’d walked past to get to Stephenson Road, with their beams and angular structure. As a child she remembered peeping into the six large bedrooms and shivering in the gloomy parlour with stuffed dead animals.

Elenor took a deep breath and lifted the brass door knocker gleaming in pride of place, a lion’s head. Again, Elenor had a renewed sense of foreboding.

The woman who answered the door scuttled about like a nervous mouse.

‘Welcome, Miss Cardew. I’m your aunt’s housekeeper.’

Elenor stepped inside the dark hallway.

‘Thank you. Please, call me Elenor.’

She handed her coat to the housekeeper who busied herself hanging it in a large cupboard.

‘Mrs Matthews has given instruction you will meet in the parlour before she retires for the evening, after which you will eat.’

With a nod the woman left Elenor’s side. Bemused, Elenor left her case propped against the wall, and made her way to the parlour.

After an arduous journey, the last thing Elenor wanted was to entertain her aunt with information about her brothers and the farm. She wanted to put the twins to the back of her mind.

She pushed open the door and stepped into the gloomy room. It was cold to the point of unfriendliness. She was, however, grateful to note the absence of the stuffed animal heads.

Porcelain dogs and lace cloths did nothing to brighten the drab.

Unsure as to where her aunt would sit, Elenor chose to perch on the edge of the sofa, a hard piece of furniture never designed for comfort. A mantle clock ticked and Elenor shivered. A fire in the room would not go amiss. As she debated the idea, the door swung open and her aunt entered. Elenor jumped to her feet. Far from looking frail, her aunt, dressed in her usual ill-fitting black outfit, marched straight up to Elenor and stared her in the face.

‘Didn’t get the good looks of your mother then. Sit down.’ She banged her walking stick on the floor.

Shocked, Elenor did as she was told.

‘Hello, Aunt Maude. How are you?’

‘Ill. Why do you think I sent for you, girl? I’m unwell. Not that you bumpkins from the country would ever care. Not one of you has written me. Oh no, but you accept the money swift enough. It is heartening to see you do not spend it on frivolous clothing.’

Uncomfortable that her clothing had drawn scathing comments from her aunt, Elenor adjusted her dress and sat back in the seat.

‘Don’t get too comfortable. You are here to work. To look after me. Go and fetch me a light supper. Tell that thing I employ to keep this place that she is to air my bed. I feel fatigued with entertaining guests.’

Elenor rose from the seat and fought back the urge to curtsy on her way out. She hurried down to the kitchen and welcomed the warmth of the room. It had a light airy feel due to the floor-to-ceiling cream cabinets and windows looking out onto a small garden. The housekeeper, although far from tall, was bent over a white stone sink. Elenor gave a polite cough.

‘Excuse me – oh, I’m sorry I don’t know your name. My aunt would like a light supper before she retires, and her bed aired please.’

The woman turned around and Elenor could now see she was much younger than she looked when they first met in the dark hallway. Certainly, no older than thirty.

‘Certainly, Miss Cardew. I’m Victoria Sherbourne. You’ve had a long journey, miss. You must be famished. I’ll see to your aunt and you can sit here with a cup of tea while I ask if she wants you to eat with her. Her mind changes like the wind. Pour yourself a cup whilst I prepare her tray.’ She pointed to the teapot.

As she sipped the strong tea, Elenor wondered over her role attending to her aunt’s needs. The woman didn’t look ill and appeared perfectly capable. The housekeeper interrupted her thoughts.

‘My husband enjoys her company and she tolerates his.’

‘Your husband?’

Victoria busied herself with the tray.

‘Yes, George. He’s away at the moment. As a private tutor he likes to attend various talks by other masters.’

‘I look forward to meeting him.’

Elenor noted a slight flush to Victoria’s face when she spoke about him. Pride? Embarrassment? She couldn’t tell.

Victoria returned with the tray after seeing to Aunt Maude.

‘Come, I’ll show you to your room. Your aunt has gone to bed. She asked me to tell you she will breakfast with you at eight in the morning. Unpack your case and I’ll bring you a light supper on a tray.’

‘That’s very kind of you, Victoria, but it will take me all of two minutes to unpack, and I’d rather eat downstairs in the kitchen if I’m not in your way. It’s such a cosy room.’

As they reached the bedroom, Victoria pushed open the door and set down the case and bag. Elenor had no time to take a look before Victoria closed it again.

‘We’ll eat together,’ Victoria said.

Returning to the kitchen, Victoria prepared a plate of cold meat, cheese and hard-boiled eggs and set the table for two. She carved her way through a fresh loaf of crusty bread.

‘A simple supper, but one I’m sure you can manage. It’s been a long day for you.’

Elenor stifled a yawn and helped herself to a plate of food.

‘I will sleep well tonight. Mind you, the journey was nothing like the hard work I usually have every day. I’m not used to sitting around all day, and if my aunt wants me to read to her for hours, well, I fear for my sanity.’

Victoria burst out laughing.

‘I can’t imagine your aunt having the patience to sit and listen. She will probably have you writing letters. She gets violent head pains and her eyes are not as strong as they once were. My husband used to write for her, but he is not always available.’

Shaking her head, Elenor pulled a face.

‘My handwriting isn’t the neatest. She might ask me once, but I very much doubt I’d be asked twice.’

She looked around the kitchen and saw a skipping rope and a wooden top sitting on top of a stool by the back door.

‘Do you have children, Victoria?’ she asked, pointing to the toys.

‘Yes. A daughter. Rose.’

‘Rose. A pretty name. How old is she?’

‘Five in November.’

‘How wonderful, a little girl. I take it she’s asleep, I look forward to meeting her tomorrow.’

‘She’ll be no bother. I keep her busy. I can’t have the girl running around making a nuisance of herself,’ Victoria said as she cleared away dishes.

Tiredness crept in and Elenor stretched out and gave a yawn.

‘Thank you for supper, Victoria. I look forward to meeting your family. Goodnight.’

‘Goodnight, Elenor. I’ll give you a knock in the morning.’

Victoria put the dirty dishes in the sink.

Elenor smiled as she recalled the dishes in the sink at Tre Lodhen. No doubt that evening the inn enjoyed a visit from two miserable brothers.

Chapter 5

A good night’s sleep and no pre-dawn work found Elenor in good spirits. She pulled open the drab brown curtains to let in a hint of sunshine. The rays bounced into the room and offered up an orange glow but failed to fight the drab brown and black.

The view was south-facing into the avenue with a row of trees on both sides. Her surroundings in Cornwall were far more attractive and a pang of homesickness caught hold. A tap at her door interrupted her thoughts and she opened the door to Victoria who stood holding a tray bearing a pot of tea and a china cup.

‘Morning, Victoria.’

‘Morning. Your aunt will be ready in half an hour.’ She placed the tray onto the dressing table and wiped her hands down her pale blue pinafore.

‘The bathroom is free. There is plenty of hot water.’

‘Thank you.’

Grateful for the warmth from the teacup on her hands, Elenor sipped it with speed. She ventured to the bathroom across the hall. Another cold room where her breath puffed into clouds. The large mirror steamed over the moment she ran the hot tap. A large bar of Pears soap sat on the pretty scalloped edged sink, so delicate compared to the stone affair of the farmhouse. The chilly air prevented her from lingering and she promised herself a treat of an uninterrupted bath another time.

Back in her room Elenor pulled out her fresh dress from the wardrobe. Realising the dress would not protect her fully from the chill of the day she wore her brown cardigan with a mismatched button at the bottom, which had seen better days but kept her warm. She pulled on thick brown stockings, darned at the heel and toe within an inch of their life and hooked them onto a thin, well-worn suspender belt. With a sigh, she slipped her feet into a lace-up pair of scuffed but polished, brown brogues, stuffed with the obligatory scraps of cloth to prevent slipping. Once upon a time they were her mother’s pride and joy. Sadly, Elenor could not look upon the shoes with the same enthusiasm as her mother had; to Elenor they smacked of poverty and hardship.