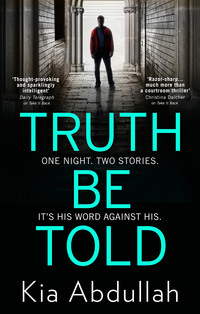

Truth Be Told

‘What about women who get date raped?’

‘Well, that’s different,’ Salma insisted. ‘Women are physically weaker. I just don’t think it’s the same with a man against a man.’

Zara digested this. The shame of male rape was caused exactly by statements like this. The stigma of weakness was thick and cowing. ‘I don’t think that’s right,’ she said, ‘but to answer your question: I don’t know very much about him yet.’

‘Is he gay?’

‘I can’t say for sure.’

Salma shook her head with wonder. ‘God, it must be hard. I’m glad we don’t have to deal with that.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, there’s no such a thing as a gay Muslim, is there?’

Zara blinked. ‘I don’t think—’

‘I mean, I know they’re out there,’ Salma interrupted. ‘But what I don’t get is why people like that cling to religion. I don’t have anything against gays obviously, but if you are gay, how can you still be Catholic or Muslim?’

Zara studied her sister. There was no malice in her tone, just a curious ignorance. ‘It’s more complicated than that.’

‘I don’t think it is,’ said Salma. ‘You’re either this or that. You can’t be both.’

Zara tried to decide if it was worth fighting this battle, for she knew she wearied her sisters. They were gentle in their joshing – ‘Zara the Brave comes to the rescue!’, ‘Zara the Brave will conquer you!’ – but there was some truth behind the humour. Her refusal to let things lie or concede an inch of ground often made their debates exhausting.

Zara took a sip of her tea, then met Salma’s gaze. ‘Okay, what if one of your boys – let’s say Yakub – turns sixteen in a few years and tells you that he’s gay. How would you react?’

‘Well, I mean…’ Salma flexed her shoulders as if gearing for a fight. ‘I would accept it.’

‘So there would be no angry arguments, no tears, no tantrums?’

Salma hesitated. ‘Well, there would be tears but only because I’d be scared for him. Life is hard enough and this would only make it harder.’

Zara nodded. ‘Okay, but there would be no cataclysmic event? No kicking him out of the house? No disownment? No sending him to Bangladesh?’

Salma flinched. ‘Of course not. What do you take me for?’

‘Okay, so he would still live in your house, cook with you, go to school, take out the bins as normal?’

‘Yes.’

‘And he’d do what his brothers would do? Play football? Go to the cinema? Spend too much time online?’

Salma’s lips curled in a half smile. ‘Yes.’

‘Would he still celebrate Eid with you?’

She shrugged. ‘Yes, of course.’

‘Would he still go to Friday prayer with his brothers?’

‘Yes.’ There was a tiny catch in her voice.

‘Would he go to janazahs at mosque?’

‘Yes.’

‘Would he still give zakat?’

‘Yes.’ Now, her voice was small.

‘You would want him to be a part of that?’

Salma was silent. Her features blanched with sorrow. ‘Yes, I would.’

‘Would you deny him any of that or expect him to remain at home?’

Her eyes grew glassy. ‘No.’

‘Okay,’ said Zara gently. ‘I guess that’s how you can be gay and Muslim.’

Salma swiped discreetly at her eyes. ‘God, I can tell you were a lawyer.’ She laughed but it was a blare of a sound, designed to mask something deeper. She picked up her cup of tea and hugged it to her chest.

Zara gently pushed the plate of biscuits back towards her sister.

Kamran pulled the blanket tighter and bunched the folds around his neck. There was something unremittingly cruel about having to be in this room. This, his supposed sanctuary, was also the scene of the crime and though he had washed his sheets three times, they still felt befouled.

He tried to give shape to the weight of his trauma. He thought of it as a thick bar of fluorescent light that hummed from throat to groin. Real healing would dim that light, snuff out sections until it grew dark – but how could he heal if he couldn’t remember? Instead, he would push down the pain until it was a sun-bright penny lodged in his gut. That’s where he’d let it burn.

A thought slithered into his mind, making his stomach clench. Perhaps the only way to understand what had happened was to talk to Finn. Together, they would talk and together they’d forget. After all, it was one drunken night. Isn’t this what happened at boys’ schools? Experimentation? Liberation? Wasn’t this just another experience?

Kamran traced his hands along the underside of the blanket: soft white fleece that sometimes came off on his clothes. He pushed his fingers into it, marshalling his strength. He took a bracing breath and tossed the blanket off him, the sweep of his arm feigning courage. He walked across the room, a stony chill on the soles of his feet, and pulled on his shoes and blazer. He glanced at the wall clock. It was 4.30 p.m. on a Thursday afternoon. Finn would be manning the housemaster’s office for at least another half hour.

He picked up his knobby metal key and walked into the hall. He felt a vinegar sting in his throat and swallowed once, then twice, to clear it. He descended three flights to the housemaster’s office and knocked on the open door.

‘Come in,’ called Finn before looking up.

Kamran stepped inside, his loafers clicking flatly on the polished wooden floor.

Finn smiled. ‘Hadid Major. How may I help you today?’

Kamran closed the door behind him. ‘May I sit?’

Finn gestured generously. ‘Of course.’ As assistant to the housemaster, he was used to pupils asking for his time.

Kamran sat in a chair, a large Chesterfield of squeaky burgundy leather. He traced the padded armrest, his fingers dipping in the seams between.

‘Problems?’ asked Finn.

‘I… I’ve come to talk about Friday.’

‘Oh?’ Finn checked his desk calendar. ‘Friday the eighth?’

Kamran tensed. ‘Friday the first. I want to talk about what happened.’

Finn smiled accommodatingly. ‘Okay.’

Kamran waited. ‘I want you to tell me what happened.’

Finn frowned. ‘With what?’

‘With us.’

His chin tilted at an angle. ‘With us?’

Kamran felt a flare of anger. ‘Stop playing the idiot. Look, I don’t want this to go any further. I just want to understand what happened.’

Finn sat back in his chair, his lips poised in a patient smile. ‘Kamran, do you want to tell me what you’re talking about?’

‘Friday night!’ His voice was high and bitter. ‘You were in my fucking room!’

Finn tensed, his features strained with alarm. ‘Look, before you say anything else, I want to tell you that I—’

‘You what? That you’re a faggot!?’

Finn blanched. ‘Don’t use that ugly word.’

Kamran felt his conscience spark but it was snuffed out by anger.

‘What happened?’ asked Finn. ‘Did someone spot us or—’

‘How could you do it?’ spat Kamran.

Finn held up a defensive hand. ‘Look, it takes two to do what we did.’

Kamran jabbed a finger at him. ‘Don’t you say that. Don’t you dare fucking say that.’

‘I… what do you want me to say?’

‘Tell me what happened. Tell me exactly what happened.’

Finn grimaced. ‘You know what happened.’

‘No, I fucking don’t!’ He clenched his fingers around the arm of his chair. ‘I want you to tell me.’

Finn exhaled quietly. ‘Okay, well, firstly, we were both drunk. You know I went to the spring fundraiser.’

‘How much did you drink?’

‘Too much.’

‘How much?’

Finn hesitated. ‘About seven drinks.’

‘What do you remember?’

‘I don’t. Not really. I was coming back from the party. It was about two. I went to your room and—’ He shrugged. ‘Well, I don’t need to spell it out.’

Kamran stared at him. How could he be so casual about it? ‘Are you gay?’ he asked.

Finn made a small sibilant sound. ‘Well, yeah. What do you think?’

‘You disgust me.’

He flinched. ‘Don’t say that.’

Kamran felt a spike of emotion: a profound urge to hurt him.

Finn scooted his chair forward. ‘Listen, I’m sorry.’ He laid a hand on Kamran’s wrist. ‘I know what your family would say and you might not want to admit it, but you know it was consensual.’

Kamran shook off his hand. ‘Don’t fucking touch me.’ He jolted up from his chair, his armpits sliding with sweat. ‘Don’t you ever touch me again.’ His skin burned with a white-hot hate. ‘Stay the fuck away from me.’ Kamran fled from the office.

What had he expected? That Finn would break down and cry? That he would deny everything? His insistence that Kamran consented was a violation of a different type: of not knowing his own mind.

But wasn’t it true in a way? Hadn’t he been so drunk that night that he hadn’t even locked his door? And hadn’t he reacted in the past to Finn’s overtures? A hot embrace on the rugby field, a reciprocal smile to his charming grin?

Is this what women go through? he wondered. A painstaking examination of each innocent action; holding cloth to light to find a sullied patch. Had Finn targeted him specifically or had he walked down the hall, twisting every handle? Was there a chance that Finn had really been drunk and not known what he was doing? Had he simply fallen into a bed only to find a warm body waiting?

Kamran put himself in Finn’s shoes; pictured himself stumbling into a room, falling into a bed, finding a sleeping woman there with soft limbs and warm breath. Would he be tempted too? Would it feel like an act of violence or just like coming home? If he found Maya in his bed, wouldn’t he too take off her clothes? Was he a potential rapist too?

Rape. The word was so harsh, so emotive. It almost did a disservice to the victim. It made the crime sound so heinous, the stench of it so strong, that one loathed to impose it on bright-eyed men, especially ones who looked like Finn.

But Finn was a rapist and what happened was an act of violence. It was true that Kamran did not fight, but neither did he consent. Finn had walked into his room uninvited and put himself inside his body, turning Kamran into a rape victim. The label was a noose round his neck, making his throat clot with muscle.

It takes two to do what we did.

How dare Finn say those words? How dare he cast Kamran as a co-conspirator? Had he done this before? Was he relying on the fact that his victims would stay silent, cowed by the spectre of shame?

Kamran felt the tang of metal in his mouth, the acid flavour of fear. He realised that he had to do it. He had to seek justice. There was no easy route from this. He picked up his phone and drafted a message to Zara. Gripping it in his fist, he left the room and headed to the green. He walked away from West Lawn until the signal grew stronger. He watched the bars grow one by one and then, with the beat of his heart going too fast, he took a deep breath and pressed send. The message contained four words that were sure to upend his life. Help me stop Finn.

Zara leaned forward so that the lamp suspended on a stem above her head didn’t shine directly on her. The restaurant was a blocky, overlit affair with art-deco prints in black, white and green. Idly, she leafed through the menu. Safran had texted her to say he’d be late. It was the lawyer’s burden, she knew. They were punctual in matters of work but often at the expense of friends. She remembered her time in chambers and how friends would lay bets on how late she would be. It was sad that she rarely saw them anymore, their time squeezed by careers and kids. In fact, Safran was the only friend she saw with any frequency.

As she waited, her hands went restlessly from her lap to her glass to her knife. She straightened her napkin so that it sat flush against the menu, inching the fork just so. Since she’d stopped taking Diazepam, she noticed herself doing this more. She had always liked neatness and order, but never before would she set her alarm five or six times in a ritual, nor would she reread an email three times before sending it off. Sometimes, she found herself reading a line over and over, especially when it came to lists. She would tell herself to stop being ridiculous and yet she’d repeat the phrase, telling herself ‘one last time, one last time’. At first, she thought it was simply withdrawal but after five weeks it still hadn’t passed. At least it followed a sequence, she reasoned. Though the act itself was irrational, the neat rituals were entirely predictable and so she didn’t seek advice. It was, after all, just a state of mind.

She glanced at her watch and ordered a lime and soda, but instead of taking a sip, she spun the glass in her palms and morosely watched the crowd: media types and city bankers. Finally, she spotted Safran who cut his way across the room and met her with a hug.

‘Sorry, sorry,’ he said, stripping off his coat and tossing it on the back of his chair. ‘There was an emergency.’

She raised a hand. ‘I get it.’

He smiled, his left dimple dipping in his cheek. ‘Thank you.’ He nodded at a waiter who hurried over to take their order. Safran had a way about him, an easy manner that made others keen to please him.

He loosened his tie and slung it over his coat. ‘So guess what?’ he said.

‘What?’ Zara smiled instinctively.

‘I’m going on a date with a doctor tomorrow.’

‘Really?’ She feigned confusion. ‘When did Leonardo DiCaprio date a doctor?’

Safran grinned and conceded the jibe. In chambers, they’d had a running joke that Safran’s exes were DBD: Dumped By DiCaprio. Like the actor’s, Safran’s girlfriends were usually tall, slim and blonde. ‘Well, this may surprise you,’ he said, ‘but actually she’s Pakistani.’

‘No!’ Zara’s jaw dropped in mock surprise.

He gave her a sheepish look. ‘Okay, don’t laugh, but I saw her at a wedding and made the mistake of telling my brother that I thought she was pretty. He told his wife who told her mum who told an auntie and suddenly, the girl’s being proffered like a slice of lamb.’

‘Well, it’s your own fault for being such an eligible barrister.’

He laughed. ‘Maybe I’ll like her.’

‘Maybe you will.’ She felt a shimmer of discomfort at the prospect of Safran meeting someone serious. What would follow? Marriage? Kids? The natural wastage of another friendship? There was nothing romantic between them but she relied on him more than she liked to admit. He was a source of logic and calm; the person she’d call if in trouble. She thought of all the friends she had lost. One by one, they were pulled away by life, work and parenthood and then there was just her, no one to call for an impromptu coffee. Safran was the only one.

‘Hey,’ he said, coaxing her back. ‘You okay?’

‘Yeah.’ She swallowed. ‘I’d be really happy for you, Saf.’

‘Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Marrying an Asian doctor is such a cliché.’

‘And being an Asian lawyer isn’t?’

He laughed. ‘I’ll give you that.’

They ordered food – grilled steak for him and a sea bream fillet for her – and ate with the unselfconscious gusto of old friends, sharing memories and anecdotes from their time in court.

After the meal, they took a stroll in the mild May air, drifting naturally towards the river. The Thames was steely in the fading light and birds wheeled in the sky above. HMS Belfast stood like a shield as they descended the steps to the riverbank. The air was smoky and the chatter from the nearby restaurants added a comforting hum.

‘How’s the family?’ asked Safran.

‘Oh, you know,’ she said.

‘No, I don’t.’

She smiled faintly. ‘They’re fine. I saw them earlier this week.’

‘Was it okay?’

‘Yeah, but I got into a bit of a thing with Salma.’

‘Oh?’

‘Yeah. It’s so fucking weird being Muslim.’

He stopped and turned to look at her. ‘What do you mean?’

‘I wish people came with a barometer, so you could tell by looking at them how conservative they are. Will they judge you for drinking? Or wearing jeans? Or showing a bit of wrist? Where do their lines of liberalism lie? Do they have sex outside marriage? Or do they expect you to be in niqab? Like, how comfortable can I be with you? How much of myself can I show to you?’

Safran studied her. ‘Where’s this coming from?’

Zara gestured eastwards vaguely towards her mother’s home. ‘Salma. She was saying you can’t be both gay and Muslim and I was surprised by that.’

‘Why? That’s not such a radical thing to say.’

She glanced up at him. ‘You don’t think?’

‘No.’ He leaned his elbows on the cast-iron gate. ‘I’m going to sound cynical but the world is built of cliques. I’m not saying that’s right but it’s true. Some cliques are relatively small – like Old Etonians – and some cliques are huge – like Muslims – and in this drive for inclusion, we want to say that anyone is welcome anywhere and anyone can become anything but that’s not true. If you didn’t go to Eton, you can’t be an Old Etonian. If you’re gay, then it’s hard to also be a Muslim.’

Zara arched a brow. ‘See, this is what I mean about a barometer. I thought you were more liberal than that.’

He shook his head. ‘It’s not about conservative versus liberal or tolerance versus intolerance. It’s just logic.’

‘So if someone told you they were a gay Muslim, you’d think they were wrong to call themselves that?’

He shrugged. ‘They can call themselves what they like. I don’t have an issue. I just think we need to stop trying to bend things to our will when they clearly don’t fit.’

Zara was surprised. Safran often played the contrarian but usually from a place of empathy.

He saw the look on her face and softened his tone. ‘Look, I’m talking from a logical standpoint. If you’re gay and you want to fall in love and have sex and enjoy the fruits of being alive, maybe you’re better off without the Islamic faith.’

Zara was affronted. ‘That’s a cold way to look at it.’

‘Maybe,’ he said mildly, ‘but I also think it’s true.’

Zara studied him, confounded by his casual dismissal. She wanted to debate and fight, but could see from his unruffled stance that his conviction was immovable. What chance did they have at progress when even men like Safran held tightly to tradition?

She turned to the Thames and watched the slate-grey waves fold onto the shore. There, standing next to her closest friend, she wondered if you ever really knew anyone at all.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов