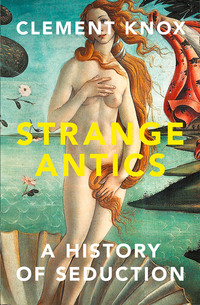

Strange Antics

The vibrancy of London life attracted the concern of moralists as well as the condescension of snobs. The neighbourhoods around the Tower, the aptly named Tower Hamlets, were the epicentre of the movement to transform English manners. The freedoms enshrined in the post-1688 settlement were extended only grudgingly to the common people. The recognition that the state could no longer prescribe moral and religious conformity from the top down was balanced by a countervailing belief that individuals were amenable to suasion, instruction and shame from the bottom up. Encouraged by Queen Mary, citizens in Tower Hamlets set up a Society for the Reformation of Manners in 1690 to suppress brothels and to stymie immoral behaviour in their community. Over a dozen companion societies were active elsewhere in the city by the mid-1690s, and they would remain features of London life until the 1730s, when they finally abandoned their Sisyphean task. Even if their mission was ultimately in vain, the attempt at moral reformation made a great impression on Richardson. The animating ideal of the societies – the notion that individuals were moral agents susceptible to reason, whose better impulses could be cultivated by instruction and example – was to shape his entire worldview.

One of the first glimpses we get of the young Richardson is his admission that as a teenager he sent anonymous letters to dissipated members of his community urging them to reform their ways. This was an early manifestation of his lifelong love of letter writing. A shy boy, Richardson immersed himself in books and was known in his neighbourhood for his literary abilities. His bashfulness and his way with words made him a favourite of the local women, who had him read to them while they sat at their needlework and, later, recruited him to help manage their correspondence with their suitors:

I was not more than thirteen when three of these young women, unknown to each other, having an high opinion of my taciturnity, revealed to me their love secrets, in order to induce me to give them copies to write after, or correct, for answers to their lovers letters: Nor did any of them ever know, that I was the secretary to the others. I have been directed to chide, and even repulse, when an offence was either taken or given, at the very time that the heart of the chider or repulser was open before me, overflowing with esteem and affection; and the fair Repulser dreading to be taken at her Word; directing this word, or that expression, to be softened or changed. One, highly gratified with her lover’s fervor, and vows of everlasting love, has said, when I have asked her direction: ‘I cannot tell what to write; But (her heart on her lips) you cannot write too kindly.’ All her fear only, that she should incur slight for her kindness.

Better training for an epistolary novelist can scarcely be imagined.

Richardson’s obvious intelligence and eagerness to learn put him on the path to train as a clergyman, and one can glimpse an alternative reality where he joined the ranks of the great Georgian scribbler-divines: Jonathan Swift, Lawrence Sterne and Charles Churchill. But this would have required a university education, and his family’s poverty precluded that eventuality. Unable to afford an education, in July 1706 Richardson was bound as an apprentice to John Wilde, a London printer. At any one time London had a floating population of around ten thousand apprentices, paying their dues in trades as diverse as tweezer-making, bridle-cutting and calico-printing. Bound to their respective masters for seven years and taken into their homes and families to live, work and learn, apprentices – aside from actual criminals – constituted the most suspect of London’s demographics. ‘The Blood runs warm in their young veins,’ a commentator observed in one of the innumerable tracts decrying the moral threat posed by these rampant young men, ‘against this Evil the young Apprentice must exert all the Force of Reason, Interest, and Religion.’ Morality and the urges of young manhood aside, apprentices were trapped in an economic bind: they vastly outnumbered their masters. In the printing industry there were only a hundred or so master printers, each employing at any one time between four and ten apprentices on top of a regular staff of journeymen printers. With only faint prospects of ever matching their employers’ prosperity, the loyalty of apprentices to their masters and their commitment to society as a whole was always contingent. The vast cultural effort that went into preaching to apprentices on matters of morals, manners and work ethic was symptomatic of this fear of a social group not yet integrated into the order of things. In this respect, male apprentices were the counterparts to that other group that the Georgians worried so much about: young, single women.

The most enduring artefact of this culture of suspicion towards apprentices is William Hogarth’s great cycle of etchings, Industry and Idleness. It depicts the divergent life paths of two apprentices bound at the same time to a single London weaver. The Good Apprentice, Francis Goodchild, works hard, goes to church, marries the master’s daughter, and so inherits his business, ending up a prosperous merchant who in the final scene parades through London in a carriage having recently been made Lord Mayor. The Bad Apprentice, Thomas Idle, shirks his duties as an employee and a Christian, finally running away to sea before returning to London to whore and carouse and, ultimately, commit murder, for which he is hanged at Tyburn in the penultimate plate.

Samuel Richardson was ever the Good Apprentice. ‘I served a seven diligent years to it, to a master who grudged every hour to me,’ he recalled of his apprenticeship. ‘I took care, that even my candle was of my own purchasing, that I might not in the most trifling instance make my master a sufferer (and who used to call me The Pillar of his House).’

His apprenticeship to Wilde ended in July 1713. Two years later he became a freeman of the Stationers’ Company. Moving from printer to printer, Richardson accrued experience as an overseer, compositor and corrector while searching for a patron. One of the printers he worked for was John Leake, and when Leake died in 1720 he took over his printing business in Salisbury Court, off Fleet Street. A year later, in 1721, he married his former master John Wilde’s daughter, Martha. Now thirty-two, Richardson was finally established as a husband and businessman.

Salisbury Court was to be the base of Richardson’s operations for the next four decades. Situated between Fleet Street and the Thames, the business was at almost the exact midway point between the old centre of London around St Paul’s, and the fashionable purlieus of St James’s. His immediate world was bounded to the west by the Temple Bar, the gateway that marked the boundary between Fleet Street and the Strand, between London and Westminster, and whose elaborate façade was, as occasion required, decorated with the heads of Jacobite traitors. To the east, Fleet Street was separated from Ludgate Hill and the City proper by Fleet Ditch and the New Canal, the artificial tributaries that drained much of the human and industrial effluvium of the City into the Thames, and whose stench did little to hinder the brisk business done at the countless stalls selling fresh oysters that lined their banks.[12] In between these limits thrived a neighbourhood of tailors, lawyers, clerks, doctors and tavern-owners. There were also a significant number of printers and booksellers.[13] Conveniently for Richardson, Salisbury Court was equidistant between the booksellers of west London, like Andrew Millar, the greatest literary deal-maker of the day, based on the Strand, and those in the east, on and about Paternoster Row, such as Richardson’s great friends and boosters Charles Rivington and John Osborn.

Richardson’s timing was as propitious as his location. England in the 1720s was on the verge of a great explosion of printing activity. Literacy rates were approximately 60 per cent for men and 40 per cent for women. Rising education standards combined with economic prosperity and, for the most part, social stability created a ready market for the printed word. On the supply side, a bare minimum of government intervention in printing, improving legal protections for intellectual property, and an efficient postal service, all nourished the growth of the industry. Printers were kept busy by the three thousand unique titles being published each year by the 1740s – two-thirds of which were printed in London – and by the dozens of daily, weekly or thrice-weekly newspapers, journals and gossip sheets, not to mention the sleet of Grub Street pamphleteering that rained down continuously upon the capital.

Richardson’s first big break in business came in 1733 when he was awarded a contract to print bills for the House of Commons. A decade later he won a second, considerably more lucrative contract to print the journals of the House of Commons. In between these two coups he continued to accumulate experience and trust in the book trade, his presses at Salisbury Court producing respectable tomes on history, geography, and various religious and moral matters. He engaged through his publications with some of the great intellectual debates and problems of the English Enlightenment. His presses took both sides of the fractious public discussion over Deism and demonstrated, through works like Daniel Defoe’s Religious Courtship, an emergent interest in problems of love, romance and marriage. Many of his publications, such as the Weekly Miscellany and the Daily Journal, were fantastically dull, and his authors were little better. They did however provide Richardson with entrées into literary London – the author Aaron Hill became his great friend and supporter – and his correspondence with other, lesser figures provides us with crucial insights into his life in this period. In the mid-1730s he became a friend and correspondent with Dr George Cheyne, a quack doctor and nutritionist from Bath whose books on dieting and nutrition Richardson published.[14]

It is largely through his letters with Cheyne that we get our first idea of what Richardson may have looked like. Cheyne, who had been extraordinarily fat, detailed his obesity and its consequences in horrifying detail in his letters to Richardson (he wrote on one occasion of his ‘putrified overgrown body … regularly the gout all over six months of the year, perpetual [retching], anxiety, giddiness, fitts and startings. Vomits were my only relief’), while extolling the merits of his ‘strict milk, seed, and vegetable diet’ and ‘the necessity of frequent gentle vomits that cleanse the glands’. Richardson, it emerges, was himself sorely in need of this course of treatment. Cheyne berated him for his girth and prolific appetite, and his cowed friend agreed to slim down, thereafter boasting of his progress in his letters. By the time the first images of Richardson emerge in the 1740s we see a man with a pink, round, complacent face – like a gammon steak – and a simple white wig, who, if not vastly overweight, generously fills his breeches.

Richardson’s struggles with his weight may have concealed a deeper personal torment. He was frequently ill throughout this period and at times hinted at psychological and physical exhaustion. Overwork likely accounted for some of this, but he was also haunted by familial tragedy. His marriage to Martha had produced six children – including three Samuels – none of whom survived infancy. Martha herself died in January 1731; four months later their last surviving daughter died too.[15] The next year he married Elizabeth Leake, the daughter of his former employer. Their marriage produced four daughters, Mary (Polly), Martha (Patty), Anne (Nancy) and Sarah (Sally), all born between 1735 and 1740. Richardson never had the son he hoped for, and it is quite possible that the profusion of women in his life sharpened his interest in the dynamics of courtship.

Richardson’s failure to produce a male heir indirectly led to his first outing as an author. In the summer of 1732 he engaged as his apprentice his nephew Thomas Verren Richardson, perhaps with the intention one day of handing his business over to him. Worried for the young man’s morals, Richardson took the occasion of Thomas’s apprenticeship to set down his own thoughts on how an apprentice should conduct himself. The result was The Apprentice’s Vade Mecum, printed from his own press in 1733. In its tone, content and rambling form, the Vade Mecum did but little depart from the conventions of the instruction manual. Beginning with the customary decrying of ‘the degeneracy of the times, and the profaneness and immorality, and even the open infidelity that is everywhere propagated with impunity’, it proceeded through a standard list of moral threats (women, the theatre, the tavern) that the pious apprentice would have to circumvent in the city. One of the few moments in which Richardson reveals his considerable descriptive powers comes during a critique of modern fashions, which he considered ‘one of the epidemick evils of the present age’, an especial threat to the young apprentice as it ‘lifts up the young man’s mind far above his condition’. What follows is an inadvertently hilarious description of the various modish affectations in dress that Richardson had observed in the streets of London (‘fine wrought buckles, near as big as those of a coach-horse, covering his instep and half his foot’), before ending with a prayer that the ‘ingenious Mr. Hogarth would finish the portrait’ and ‘shame such Foplings into Reformation’. There is a hard edge to Richardson’s criticism of such pretensions. The dangers of material ambition haunt all his novels. The idea that status could be purchased rather than earned through moral example was repugnant to him, and he saw in that notion’s prevalence the route by which men would be made work-shy and women would be sexually ruined.

The Vade Mecum never sold much, despite being supported by his bookseller friends and celebrated in various magazines and journals that Richardson had a hand in. But his book’s commercial failure figured little in his larger fortunes. Richardson was prospering by this point and in 1738 he began to rent a country home in Fulham, a pile with three floors, a cellar, and a garden with a grotto. While he retained his quarters in Salisbury Court, Richardson now had the perfect writer’s retreat in the countryside just west of London. No sooner had he taken up the lease than he was approached by his bookseller associates Rivington and Osborn with a commission to write a book of familiar letters. The concept – which conformed to a longstanding arrangement – was a book of letters sent from various stock characters (Mother to Daughter, Master to Servant, etc.) that doubled as a guide to letter writing and an exercise in moral instruction. Richardson agreed and set to work on these letters, to be written ‘in a common style’ for the use of rural readers. The first couple he wrote were ‘letters to instruct handsome girls, who were obliged to go out to service, as we phrase it, how to avoid the snares that might be laid against their virtue’. In the writing, Richardson recalled a story he had been told decades before. It was about a beautiful girl from a respectable but financially ruined family who was obliged as a teenager to go into the service of an aristocratic household. She faithfully served her mistress until she died and she was inherited into the service of her libertine son,

who, on her lady’s death, attempted, by all manner of temptations and devices, to seduce her. That she had recourse to as many innocent stratagems to escape the snares laid for her virtue; once, however, in despair, having been near drowning; that at last, her noble resistance, watchfulness, and excellent qualities, subdued him, and he thought fit to make her his wife, that she behaved herself with so much dignity, sweetness, and humility, that she made herself beloved of every body, and even by her relations, who, at first despised her; and now had the blessings both of rich and poor, and the love of her husband.

In a fit of inspiration Richardson laid aside the first project and began writing at speed. The product, finished in January 1740 after fewer than three months’ labour, was a novel, Pamela.

***

The basic narrative of Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded departs little from Richardson’s account of its supposed real-life model. Pamela Andrews is the beautiful, virtuous, literate girl from a recently impoverished family who is taken into the service of wealthy landowners. When her kindly mistress dies, Pamela’s services are assumed by the woman’s libertine son, Mr B—, who proceeds avidly to pursue her. His predations drive her to the point of suicide. Finally, Mr B— comes to recognise Pamela’s great moral character and, inspired by her example, undergoes a moral reformation. Thus transformed, he asks her to marry him and she, ludicrously, accepts.

The plot of Pamela needs no embellishment – it does, indeed, resist it – but the novel’s place in the history of seduction is better grasped with some additional context. First, Pamela helpfully demonstrates what kind of behaviour constituted ‘seduction’ at the dawn of the modern age. The first half of the book consists of Mr B—’s escalating attempts to claim his servant’s body. Initially, his actions are relatively innocent. He gives her books, clothes and other small objects; he offers her additional sums of money to send home to her poor parents; he showers her with attention above and beyond what her lowly status in his household warrants; he flirts with her in private. When these gambits fail, Mr B— becomes more aggressive: he kisses her against her will; he gropes her bosom; he harangues her as a ‘sauce-box’, a ‘bold-face’, an ‘artful young baggage’, a ‘little slut [with] the power of witchcraft’. Her resistance holds and his methods become truly Charterisian.[16] He hides in her room at night and surprises her while she sleeps. He kidnaps her and takes her to a private home where Mrs Jewkes, a London procuress, endeavours to corrupt her. Disguised as an elderly female servant, Mr B— enters the room Mrs Jewkes and Pamela share and tries to ravish her while his bawd holds her down. His rape frustrated (when Pamela faints, Mr B— desists), he tries to arrange a sham marriage in order to trick her into believing that they can now legitimately have sex.[17] This too, fails, and in a final throw of the dice Mr B— offers her a contract to become his kept mistress in exchange for 500 guineas, property in Kent, the use of all his servants, and ‘two diamond rings, and two pair of ear-rings, and a diamond necklace’.

The variety, ingenuity and rapacity of Mr B—’s attempts on her leave Pamela rightfully despondent. ‘This plot is laid too deep,’ she laments at one point, ‘and has been too long hatching, to be baffled, I fear.’ It is also clear, though, that such behaviour was tolerated if not celebrated as appropriate for a well-born man to undertake in pursuit of a comely woman from a lower social class. Mr B— approaches but never crosses the line of actual rape, which was a capital offence, albeit a rarely prosecuted one. As such, all his behaviour up to that point falls within the capacious eighteenth-century definition of ‘seduction’.

In this context it is remarkable that Pamela is able to hold out at all. The forces of English society are arrayed against her and yet still she, a simple serving girl, is able to maintain her resolve. What guides her is a monomaniacal interest in maintaining her chastity, a duty buttressed by her parents in their letters to her. In their correspondence they impress upon her the impassable divide between the world of material wealth and that of priceless moral precepts. When they learn early on of Mr B—’s favours to her, they immediately warn her to be on her guard against him and remind her of the immeasurable value of ‘that jewel, your virtue, which no riches, nor favour, nor any thing in this life, can make up to you’. Her parents ask her not only that she return to them to live in honest poverty rather than risk her virtue, but further that she prefer death to the loss of her chastity.

Pamela completely internalises these ideas. When Mr B— first kisses her and fondles her breasts, she writes that she ‘would have given my life for a farthing’ rather than succumb to his advances. There is an abiding significance to her refusal to sell or exchange her chastity. In an avowedly commercial age which celebrated and encouraged material wealth and accumulation, Pamela makes the claim that her virtue exists on a plane apart from the market economy. In the founding text of the modern literature of seduction, Richardson – no critic of the capitalist ethos – declares that questions of sex will not be subsumed into the rising tide of mercantile morality. The seduction narrative becomes the place where older Christian values survive the otherwise general triumph of the new values of the market and the merchant. There is a trap here, too. The elevation of virtue heightens the drama of its menace by a seducer. Things placed on pedestals have a tendency to fall from them, and the higher the column, the more devastating the impact. The counterpoint to the celebration of virtue was the loathing of its loss. ‘Moral’ men were equally comfortable venerating the virtuous and slandering the fallen. ‘A Woman discarded of Modesty,’ one book of manners advised, ‘ought to be gaz’d upon as a Monster.’[18] Another author observed that if any man of worth and substance were to learn that the object of his affections had been previously seduced, then she would undergo an immediate and irreversible transformation: ‘her beauty fades in his eyes, her wit becomes nauseous, and her air disagreeable’.[19] Consequently, virtue was a tightrope that all chaste women walked, ever aware of the chasm all about them. Henry Fielding’s Amelia would later decry the bind in which the cult of virtue put women. ‘Let her remember,’ she tells her innocent female reader, that ‘she walks on a precipice, and the bottomless pit is to receive her if she slips; nay, if she makes but one false step.’[20]

Richardson was well aware of the public fascination with the drama of that false step. From the outset he made it clear that his aim was to bait the hook of moral instruction with the worm of titillation.[21] He could not know how successful that formula would be. The first hint of his imminent success came from his wife. She read his proofs as he wrote them, and after a few weeks’ work on Pamela she would come to his study each evening and ask, ‘Have you any more Pamela, Mr. R.?’

It emerged upon publication that Mrs Richardson was not alone in her hunger for more of Pamela Andrews. First published in November 1740, Pamela went through an astonishing five editions in ten months. French and Italian translations were rapidly commissioned and were circulating on the continent within two years of the English publication.[22] In London, Horace Walpole recorded that ‘the late singular novel is the universal, and only theme – Pamela is like snow, she covers every thing with her whiteness’.

An engraving from a scene in Pamela, where Mr B— ambushes the titular heroine in the night

Pamela was originally published anonymously and as a nominally ‘true’ story. Only years later would Richardson coyly list himself as the ‘editor’ of the work. A mere handful of close friends knew that he was the author, though word soon spread through gossipy literary London. The rest of the public had to content themselves with open letters to the author published in magazines and periodicals or directed to the book’s printer – who was, naturally enough, Richardson himself.

Whether he was named or unnamed, the rapturous reception of Pamela propelled Richardson to the front line of English literary life. His friends, perhaps predictably, showered superlatives on his novel, and their letters to him strain the norms of acceptable flattery. More revealing of the general adulation that the book received was the praise that ordinary people, either unknown to Richardson or ignorant of his identity as the author, laid upon Pamela. Clergymen wrote that his book would do more good for national morals than any number of sermons; writer and editor Ralph Courteville declared that ‘if all the Books in England were to be burnt, this Book, next to the Bible, ought to be preserved’. Members of the public told how the novel had inspired them to seek the reformation of the rakes among their acquaintances, some even claiming success in the endeavour. Theatrical adaptations were written and performed; Hogarth, who a few years before had been praised by Richardson from afar, was commissioned to create a series of etchings depicting scenes from the novel.[23] Pamela was a cultural event that touched all classes. London society ladies proudly displayed their copies in public, while the villagers of Slough gathered at the blacksmith to hear the book read aloud and ran off to ring the church bells when their heroine finally married Mr B—.