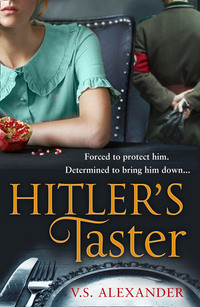

Hitler’s Taster

HITLER’S TASTER

V.S. Alexander

Copyright

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in the United States as The Taster by Kensington Publishing 2018

Published in Great Britain as Her Hidden Life by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

This edition published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2020

Copyright © V.S. Alexander 2018

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Cover photographs © Alexander Vinogradov/Trevilion Images (girl), Collaboration JS/Arcangel Images (soldier) and Joanna Jankowska/Arcangel Images (place setting)

V.S. Alexander asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008444679

Ebook Edition © September 2020 ISBN: 9780008262860

Version 2020-08-19

Dedication

To James E. Gunn, who lit the fire

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

The Teahouse

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

The Wolf’s Lair

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

The Führer Bunker

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Berchtesgaden

Chapter 23

Epilogue

Author’s Note

A Reading Group Guide

Discussion Questions

Keep Reading …

About the Author

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Berlin, 2013

Who killed Adolf Hitler? The answer lies within these pages. The circumstances surrounding his death have been disputed since 1945, but I know the truth. I was there.

Now I’m a childless old widow left alone in a house filled with memories as bitter as ashes. The linden trees in spring, the blue lakes in summer, bring me no joy.

I, Magda Ritter, was one of fifteen women who tasted Hitler’s food. He was obsessively concerned about being poisoned by the Allies or traitors.

After the war, no one, except my husband, knew what I did. I didn’t talk about it. I couldn’t talk about it. But the secrets I’ve held for so many years need to be released from their inner prison. I don’t have much longer to live.

I knew Hitler. I watched as he walked the halls of his mountain retreat, the Berghof, and followed him through the maze of the Wolf’s Lair, his headquarters in East Prussia. I was near him in his final day in the tomb-like depths of his Berlin bunker. Often he was surrounded by an entourage of admirers, his head bobbing like a buoy on the sea.

Why didn’t anyone kill Hitler before he died in the bunker? A trick of fate? His uncanny ability to avoid death? Assassination plots were hatched and, of those, many were aborted. Only one succeeded in injuring the Führer. That attempt only reinforced his belief in providence – his divine right to rule as he saw fit.

My first recollection of him was at a 1932 Party rally in Berlin. I was fifteen at the time. He stood on a wooden platform and spoke to a small crowd that grew larger by the minute as word spread of his appearance at Potsdamer Platz. Rain spit from gray clouds that November day, but each word he spoke exploded in the air until the crowd glowed with heat and rage at the enemies of the German people. With every beat of his fist to his breast, the sky shook. He wore a brown uniform with a black leather belt stretched across his chest. The red, white and black swastika patch was prominently displayed on his left arm. A pistol hung at his side. He was not particularly handsome, but his eyes held you in their powerful grip. Rumors circulated he wanted to be an architect or an artist, but I always imagined he would have been a better storyteller; if only he would have let his imagination play out in words rather than in malevolence.

He mesmerized a nation, inducing euphoric riots among those who believed in the shining new order of National Socialism. But not all of us worshiped him as the savior of Germany. Certainly not all ‘good Germans.’ Was my nation guilty of aiding the most notorious dictator the world has ever known?

A cult has grown up around Hitler, in death as large as when he was alive. Its members are fascinated by the horror and destruction he cast upon the world like the devil. They are either fanatical worshipers of the Führer or students of human psychology who ask, ‘How could one man be so evil?’ Either way, those followers have helped Hitler succeed in his quest to live forever.

I have struggled with the horrific actions perpetrated by the Third Reich and my singular place in history. My story needs to be told. Sometimes the truth overwhelms and horrifies me, like falling endlessly into a darkened pit. But, in the process, I have discovered much about myself and humanity. I have also discovered the cruelty of men who make laws to suit their own purposes.

Life has punished me and nightmares hound my sleep. There is no escape from the horrors of the past. Perhaps those who read my story will not judge me as harshly as I’ve judged myself.

CHAPTER 1

A strange fear crept over Berlin in early 1943.

The year before, I had looked up at the sky when air-raid sirens sounded. I saw nothing except high clouds, streaming like white horses’ tails above me. The Allied bombs did little damage and we Germans thought we were safe. By the end of January 1943, my father suspected the prelude to a fiery rain of destruction had begun.

‘Magda, you should leave Berlin,’ he said at the onset of the bombing. ‘It’s too dangerous here. You can go to Uncle Willy’s in Berchtesgaden. You’ll be safe there.’ My mother agreed.

I wanted no part of their plan because I’d only once, as a child, met my aunt and uncle. Southern Germany seemed a thousand miles away. I loved Berlin and wanted to remain in the small apartment building where we lived in Horst-Wessel-Stadt. Our lives, and everything I’d ever known, were contained on one floor. I wanted to be normal; after all, the war was going well. That’s what the Reich told us.

Everyone in the Stadt believed the neighborhood would be bombed. Many industries lay nearby, including the brake factory where my father worked. One Allied bombing occurred on January 30 at eleven in the morning when Hermann Göring, the Reichsmarschall, gave a speech on the radio. The second occurred later in the day when the Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, spoke. The Allies had planned their attacks well. Both speeches were interrupted by the raids.

My father was at work for the first, but at home for the second. We had already decided we would gather in the basement during an air raid, along with Frau Horst, who lived on the top floor of our building. We were unaware in those early days what destruction the Allied bombers could wreak, the terrible devastation that could fall from the skies in whistling black clouds of bombs. Hitler said the German people would be protected from such terrors and we believed him. Even the boys I knew who fought in the Wehrmacht held that thought in their hearts. A feeling of destiny propelled us forward.

‘We should go to the basement now,’ I told my mother when the second attack began. I shouted the same words upstairs to Frau Horst, but added, ‘Hurry! Hurry!’

The old woman popped her head out of her apartment. ‘You must help me. I can’t hurry. I’m not as young as I used to be.’ I rushed up the stairs to find her holding a pack of cigarettes and a bottle of cognac. I took them from her and we found our way down before the bombs hit. We were used to blackouts. No Allied bombardier could see light coming from our windowless basement. The first blast seemed far away and I was unconcerned.

Frau Horst lit a cigarette and offered my father cognac. Apparently, cigarettes and liquor were the two possessions she would drag to her grave. Bits of dust dropped around us. The old lady pointed to the wooden beams above us and said, ‘Damn them.’ My father nodded halfheartedly. The ancient coal furnace sputtered in the corner, but it couldn’t dispel the icy drafts that poked their way through the room. Our frosty breaths shone under the glare of the bare bulb.

A closer blast rattled our ears and the electricity blinked out. A brilliant orange light flashed overhead, so close we could see its fiery trail through the cracks surrounding the basement door. A dusty cloud swirled down the stairs. Glass shattered somewhere in the house. My father grabbed my mother and me by the shoulders, pulled us forward and covered our heads with his arched chest.

‘That was too close,’ I said, shaking against my father. Frau Horst sobbed in the corner.

The bombing ended almost as quickly as it had begun and we climbed the darkened stairs back to our apartment. Frau Horst said good evening and left us. My mother opened our door and searched for a candle in the kitchen. Through the window, we saw black smoke mushrooming from a building several blocks away. My mother found a match and struck it.

She gasped. The china cabinet had popped open, sending several pieces of fine porcelain, given to her by her grandmother, to the floor. She bent down and scraped the shards into a pile, trying to fit them together like a puzzle.

A cut-glass vase of importance to my mother had smashed to bits as well. My mother grew geraniums and purple irises in the small garden behind our building. She cut the irises when they bloomed and placed them in the vase on the dining room table. Their heady fragrance filled our rooms. My father said the flowers made him happy because he had proposed to my mother during the time of year when irises bloomed.

‘Our lives have become fragile,’ my father said, looking sadly at the damage. After a few minutes, my mother gave up her hope of reconstructing the porcelain and the vase and threw them into the trash.

My mother pinned her black hair into a bun and walked into the kitchen to get a broom. ‘We must make sacrifices,’ she called out.

‘Nonsense,’ my father said. ‘We are lucky to have a daughter and not a son; otherwise, I fear we would be planning a funeral not far down the road.’

My mother appeared at the kitchen door with the broom. ‘You mustn’t say such things. It gives the wrong impression.’

My father shook his head. ‘To whom?’

‘Frau Horst. Our neighbors. Your fellow workers. Who knows? We must be careful of what we say. Such statements, even rumors, could come down upon our heads.’

The electricity flickered on and my father sighed. ‘That’s the problem. We watch everything we say – and now we have to deal with bombs. Magda must leave. She must go to Uncle Willy’s in Berchtesgaden. Maybe she can even find work.’

I had flitted from job to job in my twenty-five years, finding some work in a clothing factory, filing for a banker, replenishing wares as a store clerk, but I felt lost in the world of employment. Nothing I did felt right or good enough. The Reich wanted German girls to be mothers; however, the Reich wanted them to be workers as well. I supposed that was what I wanted, too. If you had a job, you had to have permission to leave it. Because I had no job, it would be hard to ignore my father’s wishes. As far as marriage was concerned, I’d had a few boyfriends since I turned nineteen – none of them serious. The war had taken so many young men away. Those who remained failed to capture my heart. I was a virgin but had no regrets.

In the first years of the war, Berlin had been spared. When the attacks began, the city strode like a dreamer, alive but unconscious of its motions. People walked about without feeling. Babies were born and relatives looked into their eyes and told them how beautiful they were. Touching a silky lock of hair or pinching a cheek did not guarantee a future. Young men were shipped off to the fronts – to the East and to the West. Talk on the streets centered on Germany’s slow slide into hell, always ending with ‘it will get better.’ Conversations about food and cigarettes were common, but paled in comparison to the trumpeted broadcasts of the latest victories earned through the ceaseless struggles of the Wehrmacht.

My parents were the latest in a line of Ritters to live in our building. My grandparents had lived here until they each died in the bed where I slept. My bedroom, the first off the hall in the front of the building, was my own, a place I could breathe. No ghosts frightened me here. My room didn’t hold much: the bed, a small oak dresser, a rickety bookshelf and a few items I collected over the years, including the stuffed toy monkey my father had won at a carnival in Munich when I was a child. When the bombings began, I looked at my room in a different way. My sanctuary took on a sacred, extraordinary quality and each day I wondered whether its tranquility would be shattered like a bombed temple.

The next major air raid came on Hitler’s birthday on April 20, 1943. The Nazi banners, flags and standards that decorated Berlin waved in the breeze. The bombs caused some damage, but most of the city escaped unscathed. That attack also had a way of bringing back every fear I suffered as a young girl. I was never fond of storms, especially the lightning and thunder. The increasing severity of the bombings set my nerves on edge. My father was adamant that I leave, and, for the first time, I felt he might be right. That night he watched as I packed my bag.

I assembled a few things important to me: a small family portrait taken in 1925 in happier times and some notebooks to record my thoughts. My father handed me my stuffed monkey, the only keepsake I had retained throughout my childhood years.

The following morning, my mother cried as I carried my suitcase down the stairs. A spring rain spattered the street and the earthy scent of budding trees filled the air.

‘Take care of yourself, Magda.’ My mother kissed me on the cheek. ‘Hold your head up. The war will be over soon.’

I returned the kiss and tasted her salty tears. My father was at work. We had said our good-byes the night before. My mother clasped my hands one more time, as if she did not want to let me go, and then let them drop. I gathered my bags and took a carriage to the train station. It would be a long ride to my new home. Glad to be out of the rain, I entered the station through the main entrance. My heels clicked against the stone walkway.

I found the track that would take me to Munich and Berchtesgaden and stood waiting in line under the iron latticework of the shed’s vaulted ceiling. A young SS man in his gray uniform looked at everyone’s identification papers as they boarded. I was a Protestant German, neither Catholic nor Jew, and young enough to be foolishly convinced of my invincibility. Several railway police in their green uniforms stood by as the security officer sorted through the line.

The SS man had a sleek, handsome face punctuated by steely blue eyes. His brown hair folded underneath his cap like a wave. He examined everyone as if they were a potential criminal, but his cool demeanor masked his intentions. He made me uneasy, but I had no doubt I would be allowed to board. He looked at me intently, studied my identification, paying particular attention to my photograph before handing it back to me. He offered a slight smile, not flirtatious by any means, but coyly, as if he had finished a job done well. He waved his hand at the passenger behind me to come forward. My credentials had passed his inspection. Perhaps he liked my photograph. I thought it flattered me. My hair was dark brown and fell to my shoulders. My face was too narrow. My dark eyes were too big for my head and gave me an Eastern European look, presenting a face similar to a Modigliani portrait. Some men had told me I was beautiful and exotic for a German.

The car contained no compartments, only seats, and was half-full. The train would be packed in a few months with city tourists eager to take a summer trip to the Alps. Germans wanted to enjoy their country even in the midst of war. A young couple, who looked as if they were in love, sat a few rows in front of me near the middle of the car. They leaned their heads against each other. He whispered in her ear, adjusted his fedora and then puffed on his cigarette. Blue clouds of haze drifted above them. The woman lifted the cigarette occasionally from his hands and sucked on it as well. Soon thin gray lines of smoke trailed throughout the cabin.

We pulled out of the shed in the semi-darkness of the rain. The train picked up speed as we rolled away from the city and past the factories and farmlands south of Berlin. I leaned back in my seat and pulled out a book of poems by Friedrich Rückert from my suitcase. My father had presented it to me several years ago thinking I would enjoy the Romantic author’s poems. I never took the time to study them. The gift meant more to me than the verses inside.

I stared blankly at the pages and thought only of leaving my old life for a new life ahead. It troubled me to be going so far from home, but I had no choice thanks to Hitler and the war.

I found the inscription my father had written when he gave me the book. It was signed: With all love from your Father, Hermann. When we’d parted last night, he seemed old and sad beyond his forty-five years, but relieved to be able to send me to his brother’s home.

My father walked with a stoop from constant bending during his shift at the brake factory. The gray stubble he shaved each morning attested to the personal trials he endured daily, among them his dislike for National Socialism and Hitler. Of course, he never spoke of such things; he only hinted of his politics to my mother and me. His unhappiness ate at him, ruined his appetite and caused him to smoke and drink too much despite such luxuries being hard to come by. He was nearing the end of the age for military service in the Wehrmacht, but a leg injury he suffered in his youth would have disqualified him anyway. From his conversations, I knew he held little admiration for the Nazis.

Lisa, my mother, was more sympathetic to the Party, although she and my father were not members. Like most Germans, she hated what had happened to the country during the First World War. She had told my father many times, ‘At least people have jobs and enough food to go around now.’ My mother brought in extra money with her sewing, and because her fingers were nimble, she also did piecework for a jeweler. She taught me to sew as well. We were able to live comfortably, but we were not rich by any means. We never worried about food on the table until rationing began.

My mother and father did not make an obvious display of politics. No bunting, no Nazi flags, hung from our building. Frau Horst had put a swastika placard in her window, but it was small and hardly noticeable from the street. I had not become a member of the Party, a fact that caused my mother some consternation. She believed it might be good because the affiliation could help me find work. I hadn’t given the Party much thought after leaving the Band of German Maidens and the Reich Labor Service, both of which I lazed through. And I wasn’t sure what being a Party member actually meant, so I felt no need to give them my allegiance. War churned around us. We fought for good on the road to victory. My naïveté masked my need to know.

I continued thumbing through the book until the train slowed.

The SS man at the station appeared behind my right shoulder. He held a pistol in his left hand. He strode to the couple in front of me and put the barrel to the temple of the young man who was smoking the cigarette. The woman looked backward, toward me, her eyes filled with terror. She seemed prepared to run, but there was nowhere to go, for suddenly armed station police appeared in the doorways at both ends of the car. The SS man took the pistol away from the man’s head and motioned for them to get up. The woman grabbed her dark coat and wrapped a black scarf around her neck. The officer escorted them to the back of the car. I dared not look at what was happening.

After a few moments, I peered through the window to my left. The train had stopped in the middle of a field. A mud-spattered black touring car, its chrome exhaust pipes spewing steady puffs of steam, sat on a dirt road next to the tracks. The SS man pushed the man and woman into the back of the car and then climbed in after them, his pistol drawn. The police got in the front with the driver. As soon as the doors closed, the car made a large circle in the field, cut a muddy swath through the grass and then headed back toward Berlin.

I closed my eyes and wondered what the couple had done to be yanked from the train. Were they Allied spies? Jews attempting to get out of Germany? My father had told us once – only once – at the dinner table about the trouble Jews were having in Berlin. My mother scoffed, calling them ‘baseless rumors.’ He replied that one of his co-workers had seen Juden painted on several buildings in the Jewish section. The man felt uncomfortable even being there, an accident on his part. Swastikas were whitewashed on windows. Signs cautioned against trading with Jewish merchants.

I thought it best to keep my thoughts to myself and not to inflame a political discussion between my parents. I felt sad for the Jews, but no one I knew particularly liked them and the Reich always pointed blame in their direction. Like many at the time I turned a blind eye. What my father reported might have been a rumor. I trusted him, but I knew so little – only what we heard on the radio.