How to Build a Car

I’m happiest when working on a big regulation change. Drawing the RB7, the 2011 car, was just such a time: an overhaul that included the incorporation of the KERS system (it stands for ‘kinetic energy recovery system’), which stores energy in a battery under braking and then releases it during acceleration.

Other designers were saying that the best place to put the battery was under the fuel tank: it’s nice and central, it’s in a relatively cool location and it’s easy to connect from a wiring point of view. But aerodynamically, I wanted to get the engine as far forward in the chassis as possible so as to allow a very tight rear end to the bodywork, and the best way to achieve that was to take the heavy KERS battery and put it near the back of the car, which in turn would allow the engine to be moved forward to keep the weight distribution balanced. My suggestion was that we put the battery behind the engine, in front of the gearbox.

Figure 1: Placement of the KERS system in the RB7.

Initially I proposed this to Rob Marshall, our chief designer. His reaction was a deep breath. You want to take the batteries, which we know are a difficult thing to manage, very sensitive to vibration, prone to shorting out, sensitive to temperature – you want to take these and put them between the engine and the gearbox, one of the most hostile environments on the car? Really?

I was insistent. I said, ‘Look, Rob, I’m sorry, and I know it’s difficult, but not only does putting them in this location give us a good advantage, but it’s an advantage we’ll have locked in, because it’ll be impossible for a team to copy that within a season, it’s such a fundamental part of the architecture of the car.’

So Rob went away and started talking to his engineers in the design office, and came back and said, ‘No, everybody agrees, it’s just not possible, we can’t do it.’

My feeling was that it ought to be possible, so I drew some layouts that split the battery into four units, two mounted inside the gearbox case just in front of the clutch and two mounted alongside but on the outside of the gearbox case. I drew some ducting to put the batteries into their own little compartments with cold air blowing over them in addition to the water-cooling they have anyway.

Fortunately Rob is not only a very creative designer but also a designer who understands that if there is an overall performance benefit to be had, and if it looks viable, you’ve got to give it a go. It was a brave, I guess you could argue an irresponsible decision, in that if we hadn’t got it to work it would have compromised our season.

It took longer than I hoped. During the early part of the season, the KERS system was in the habit of packing up and was constantly in danger of catching fire. But once we made it reliable, we had this underlying baked-in package advantage that we were able to carry for the balance of that season and the next two, a key part of the 2011, 2012 and 2013 championship-winning cars. Which, as you can imagine, appealed to my inner love of continuity.

If the fact that I still use a drawing board and pencil sounds old-fashioned, that’s nothing compared to my start in education. At four I was sent to the local convent school where I was told that being left-handed was a sign of the devil. The nuns made me sit on the offending hand, as though I could drive out the demon using the power of my godly bum.

It didn’t work. I’m still left-handed. What’s more, when I went from that school to Emscote Lawn prep school in Warwick, I still couldn’t write. As a result I was placed in the lower set. And what do kids in the lower set do? They mess around.

My earliest experiments in aerodynamics came during a craze for making darts out of felt-tip pens and launching them at the blackboard. We’d have competitions, and I was getting pretty good until one particular French lesson, when for reasons best known to my 12-year-old self I launched my dart straight up into a polystyrene ceiling tile. The teacher turned from the blackboard, alerted by suppressed laughter that fluttered across the room, and what he saw was a classroom full of boys with their hands clamped over their mouths and one, me, sitting bolt upright with an expression like butter wouldn’t melt.

Sure enough, he made his way through the desks to mine, about to demand what was going on, when the dart above our heads chose that moment to come unstuck from the ceiling, stall, turn sideways and bank straight into the side of his neck. Statistically, it was a one in a thousand chance. It was poetry.

That wasn’t my only caning. The other one was for rigging up a peashooter from a Bunsen burner tube and accidentally tagging a science teacher instead of the mate I was aiming at.

Speech days were especially boring. On one particular occasion, me and my friend James had been playing in the woods, found some aerosol cans and lobbed them on the school incinerator. Expecting them to blow up straightaway, we took cover behind some trees, only to be frustrated by a distinct lack of pyrotechnics. Eventually we got tired of waiting and wandered off.

Shortly after that, speech day commenced, parents assembled and we took our seats, ready to be bored rigid, when suddenly from the woods came a series of booms and the stage was showered in ash. James and I looked at each other gleefully, but we counted ourselves lucky not to be caught and punished for it.

When it came to the challenge of making a hot-air balloon, I was able to put to good use my interest in building things. By this time I was beginning to understand the concept that if you want something to go up, you need to make it big in order to achieve a good volume-to-surface-area ratio, so I made a large balloon out of tissue and bent coat-hangers, complete with solid-fuel pellets for heat. Unfortunately the pellets didn’t generate enough oomph to get the balloon airborne, so I carted my dad’s propane burner into school and used that instead. The headmaster came out to see what was going on, leant on the burner and burnt his hand, which cemented his dislike of me.

At home I continued messing about with motor cars. In 1968 Dad bought a red Lotus Elan in kit form (other families had large saloons, we had sporty two-seaters), which according to Lotus you could build yourself – ‘in a weekend’, although even Dad could never manage that – and save on car purchase tax. Manna from heaven for an obsessive tinkerer like my dad, and I was his willing helper, happy to put up with his occasional, volcanic loss of temper in order to watch a car being built from a kit.

Meanwhile, I’d started building model kits. Most of my friends were making Messerschmitts and Spitfires but naturally I preferred cars, and my favourite was a one-twelfth-scale Tamiya model of a Lotus 49, as driven by Jim Clark and Graham Hill.

This was the first year that Lotus and their founder Colin Chapman had introduced corporate sponsorship, so the model was liveried in red, white and gold and had all the right details, moving suspension, the works. It was a great model by any standard, but what was especially noteworthy from my point of view was that the parts were individually labelled. Suddenly I was able to put a name to all the bits and pieces I’d see on the floor of the garage. ‘Ah, that’s a lower wishbone. That’s a rear upright.’ This, to me, was better than French lessons.

By 12 I began to get bored of putting together other people’s designs and started sketching my own. I was drawing constantly by then – it was the one thing I was good at, or, rather, the one thing I knew I was good at – as well as clipping pictures out of Autosport and copying them freehand, trying to reproduce them but also customise them at the same time, adding my own detail.

Needless to say, as I look back on my childhood now, I can identify where certain seeds were planted: the interest in cars, the fascination with tinkering – both of which came from my dad – and now the first flowerings of what you might call the design engineer’s mind, which even more than a mathematician’s or physicist’s involves combining the artistic, imaginative left side of the brain – the ‘what if?’ and ‘wouldn’t it be interesting to try this?’ bit – with the more practical right side, the bit that insists everything must be fit for purpose.

For me, that meeting of the imagination with practical concerns began at home. In the garden was what my father called a workshop but what was in fact a little timber hut housing some basic equipment: a lathe, bench drill, sheet-metal folding equipment and a fibreglass kit. In there I set up shop, and soon I was taking my sketched-out designs and making them flesh.

I’d fold up bits of metal to make a chassis and other bits out of fibreglass. Parts I couldn’t make, like the wheels and engine, I’d salvage from models I’d already put together. None of my school friends lived close by, so I became like a pre-teen hermit, sequestered in the shed (sorry Dad, ‘the workshop’), beavering away on my designs with only our huge Second World War radio for company. I spent so much time in there that on one occasion I even passed out from the chloroform I used to clean the parts with.

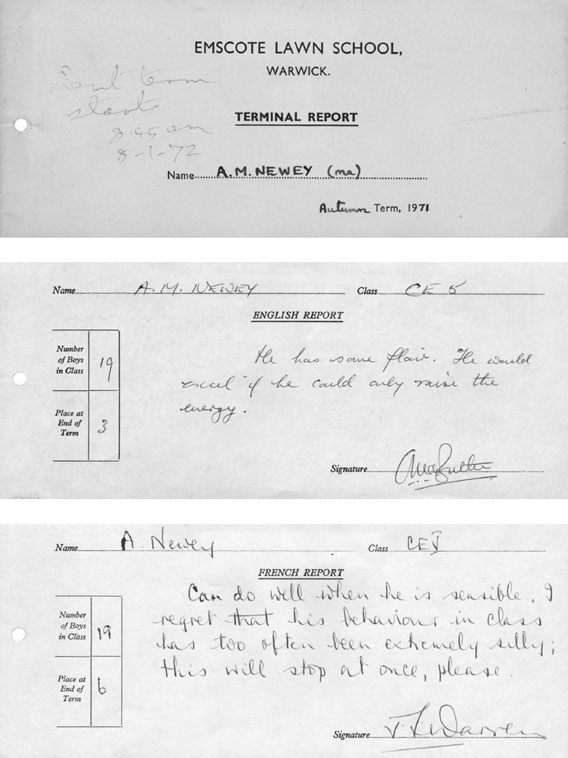

Back at school, I employed my models for a presentation, which was well received considering how mediocre I was in every other aspect of school life. ‘Can do well when he is sensible. I regret that his behaviour in class has too often been extremely silly,’ blustered my traumatised French teacher in a school report. ‘Disinterested, slapdash and rather depressing,’ wrote another teacher.

The problem was that I shared traits inherited from both my mother and my father. My mum was vivacious and often flirtatious, a very good artist but mostly a natural-born maverick; my dad was an eccentric, a veterinarian Caractacus Potts, blessed or maybe cursed with a compulsion to think outside the box. No doubt it’s an equation that has served me well in later life, but it’s not best-suited to school life.

I distinctly remember a science lesson on the subject of friction. ‘So, class, who thinks friction is a good thing?’ asked the teacher. I was the only one who raised his hand.

‘Why, Newey?’

‘Well, if we didn’t have friction, none of us would be able to stand up. We’d all slip over.’

The teacher did a double-take as though suspecting mischief. But despite the titters of my classmates, I was deadly serious. He rolled his eyes. ‘That’s ridiculous,’ he sighed, ‘friction is clearly a bad thing. Why else would we need oil?’

A selection of school reports.

Right then I knew I had a different way of looking at the world. Thinking about it now, I’m aware that I’m also possessed of an enormous drive to succeed, and maybe that comes from wanting to prove I’m not always wrong, that friction can be a good thing.

CHAPTER 3

Dad loved cars but he wasn’t especially interested in motorsport. Meanwhile my passion in that area had only intensified through my early years. As a young lad I persuaded him to take me to a few races.

One such meet was the Gold Cup at Oulton Park in Cheshire in 1972, and it was there, thanks to some judicious twisting of my dad’s arm, that we’d taken the (second) yellow Elan CGWD 714K one early summer morning: my very first motor race.

At the circuit we wandered around the paddock – something you could often do in those days – and I was almost overwhelmed by the sights but mainly the sounds of the racetrack. It was like nothing I’d ever heard before. These huge, full-throated, dramatic-sounding V8 DFV engines, the high-pitched BRM V12 engines; the mechanics tinkering with them, fixing what, I didn’t know, but I was fascinated to watch anyway, inconceivably pleased if I was able to identify something they were doing. ‘Dad, they’re disconnecting the rear anti-roll bar!’

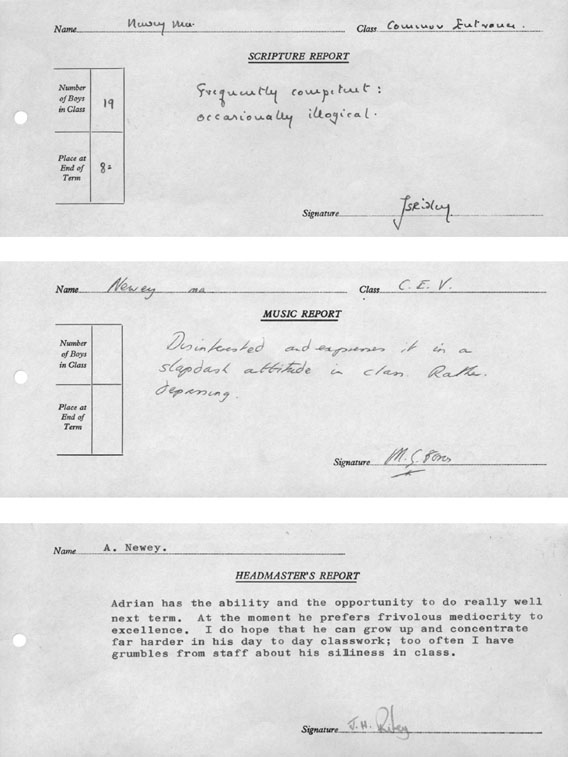

I’d seen real racing cars before. In another act of supreme arm-twisting, I’d persuaded my dad to take me to the Racing Car Show at Olympia in London. But Oulton Park was the first time I’d seen them in the wild, in their natural habitat and, what’s more, actually moving. It’s an undulating track and the cars were softly sprung in those days. I found myself transfixed by watching the ride-heights change as cars thundered over the rise by the start/finish line. I was already in love with motor racing but I fell even harder for it that day.

Posing with the Cosworth DFV engine at the Racing Car Show.

My second race was at Silverstone for the 1973 Grand Prix, where Jackie Stewart was on pole, and the young me was allowed a hamburger. Stewart on pole was par for the course in those days, but the hamburger was something of a rarity, as another of my father’s many foibles was his absolute hatred of junk food. He was always very Year Zero about things like that. When the medical profession announced that salt was good for you, he would drink brine in order to maintain his salt levels on a hot summer day. When the medical profession had a change of heart and decided that salt was bad for you after all, he cut it out altogether, wouldn’t even have it in the water for boiling peas.

That afternoon, for whatever reason, perhaps to make up for the fact that we didn’t wander around the paddock as we had done at the Gold Cup, Dad relaxed his no-junk-food rule and bought me a burger from a stall at the bottom of the grandstand at Woodcote, which in those days was a very fast corner at the end of the lap, just before the start/finish line.

We took our seats for the beginning of the race, and I sat enthralled as Jackie Stewart quickly established what must have been a 100-yard lead on the rest of the pack as he came round at the end of the first lap.

Then, before I knew it, two things happened. One: the young South African Jody Scheckter, who had just started driving for the McLaren team, lost control of his car in the quick Woodcote corner, causing a huge pile-up. It was one of the biggest crashes there had ever been in Formula One, and it happened right before my very eyes.

And two: I dropped my burger from the shock of it.

My memory is of the whole grandstand rising to its feet as the accident unfolded, of cars going off in all directions, and an airbox hurtling high in the air, followed by dust and smoke partly obscuring the circuit. It was very exciting but also shocking; was somebody hurt or worse? It seemed inconceivable they wouldn’t be. I recall the relief of watching drivers clamber unhurt from the wreckage (the worst injury was a broken leg). Once the excitement subsided it became obvious we’d now have to wait an age for marshals to clear the track. There was only one thing for it, I clambered underneath the bottom of the grandstand, retrieved my burger and carried on eating it.

At 13 I was packed off to Repton School in Derbyshire. My grandfather, father and brother had all attended Repton, so it wasn’t a matter for debate whether I went or not. Off I went, a boarder for the first time, beginning what was set to be another academically undistinguished period of my life.

Except this time it was worse, because the immediate and rather dismaying difference between Emscote Lawn and Repton was that at Emscote Lawn I was popular with other pupils, which meant that even though I wasn’t doing well in lessons, at least I was having a decent time. But at Repton, I was much more of an outcast.

The school was and maybe still is very sports orientated, but I was average at football, hopeless at cricket and even worse at hockey. The one team sport I was decent at was rugby, but at that time they didn’t play rugby at Repton, and never bothered with it for some reason. I had to satisfy myself with being fairly good at cross-country running, which isn’t exactly the surest path to adulation and popularity. I was bullied, only once physically, by two of the boys in the year above, which made my life in the first two years at Repton pretty tough. But boredom became the biggest killer, and the way I dealt with it was by retreating into sketching and painting racing cars, reading books on racing cars and making models, as well as something new – karting.

Shenington kart track. I remember it well, having persuaded my dad to take me there, aged 14. During our first visit, Dad and I stood watching other kids with their dads during an open practice day. What we quickly learnt was that there were two principal types of kart: the 100cc fixed-wheel with no gearbox or clutch, and those fitted with a motorcycle-based engine and gearbox unit.

The thing about the fixed-wheel karts was that you had to bump-start them, which involved the driver running by the side of the kart while some other poor patsy (a dad, usually) ran along behind holding up the back end, the two of them then performing a daring drop-and-jump manoeuvre. For me, it was intimidating to watch, with dads letting go of the rear end while the kids missed their footing, the driverless karts fired and then carried on serenely at about 15mph until they crashed into the safety barrier at the end of the paddock as onlookers scattered, followed by much shouting, kids in tears and so forth.

It was proper slapstick, but given my dad’s short temper I decided to go for the more expensive but easier-to-start second option.

Meanwhile, my father was making a few observations of his own. ‘As far as I can see,’ he said thoughtfully, ‘most of these boys are here not because they want to be, but because their dads want them to be.’

What could he mean? I was already sold on wanting a kart. No doubt about it. But Dad was insistent. I was going to have to prove my hunger and dedication. So he made a proposal: I had to save up and buy my own kart. But for every pound I earned, he would match it with one of his own.

During the summer holidays I worked my arse off. I canvassed the neighbourhood looking for odd jobs. I mowed lawns, washed cars and sold plums from our garden. I even managed to get a commission from an elderly neighbour to do a painting of her house and front garden. And gradually I raised enough money to buy a kart from the back pages of Karting Magazine. The kart itself was a Barlotti (made by Ken Barlow in Reading, who felt his karts needed an Italian-sounding name) with a Villiers 9E motorcycle engine of 199cc. It was in poor condition but it was a kart and, importantly, came with a trailer.

I managed to go to two practice outings at Shenington, but the stopwatch showed the combination of me and the kart to be hopelessly slow, way off even the back of the grid. In the meantime, back at Repton for a second unhappy academic year, I was at least getting on well with the teacher who ran the workshop in which we had two lessons a week. I persuaded him to allow me to bring the kart so that I could work on it at evenings and weekends. And so it was that in January 1973 my dad and I arrived at school in the veterinary surgery minivan (registration PNX 556M) with kart and trailer.

Now I could fill the long, boring periods of ‘free time’ at boarding school much more usefully – I stripped and rebuilt the engine, rebuilt the gearbox with a new second gear to stop it jumping out, serviced the brakes, etc.

The next summer holiday we returned to Shenington but, after a further two outings, the kart and I were still too slow. Simply rebuilding and fettling it had not made it significantly quicker; more drastic action was required – the engine was down on power and the tube frame chassis was of a previous generation compared to the quick boys’ karts. For the engine I needed a 210cc piston and an aluminium Upton barrel to replace the cast-iron one, funded by more washing of cars, etc., with my dad continuing to double my money. To make a new chassis was more ambitious, and for that I needed welding and brazing skills. So I booked myself on a 10-day welding course at BOC in the aptly named Plume Street, north Birmingham.

Every morning I got up at six, took the bus from Stratford to Birmingham to arrive by nine, spent the day with a bunch of bored blokes in their thirties, most of whom were being forced to take the course by their employers, and then returned home about nine.

I seemed to be quite good at welding and brazing, which meant that I progressed more quickly through the various set tasks than many of the others on the course. Some of them got quite resentful about this and started grumbling, while also taking the mickey out of my public school voice. I learnt that in circumstances such as this, I needed to fit in and began to modify my voice to have more of a Brummie accent, which was valuable when I started college. Shame it is such an unpleasant nasal drone though; I have since slowly tried to drop it again!

Armed with my new super-power, I returned to school and constructed a chassis. Over the Christmas holiday I rebuilt the engine using the Upton barrel, as well as making an electronic ignition cribbed from a design in an electronics magazine, with the help of a friend.

Come the summer term it was ready, so I rolled it out of the workshop hoping to get it going. The first time, no dice. I wheeled it back inside. Tinkered some more. I’d got the ignition timing wrong.

Another afternoon I tried again. This time, with two friends enthusiastically pushing the kart, I dropped the clutch and, with an explosion of blue smoke from the exhaust, it fired up.

Jeremy Clarkson was a pupil at Repton at the time and he remembers the evening well, having since told flattering stories to journalists, saying that I’d built the go-kart from scratch (I hadn’t) and that I drove it around the school quad at frighteningly high speeds (I didn’t).

In truth, it was more of a pootle around the chapel, but one that had disastrous consequences when one of the pushing friends took a turn, pranged it and bent the rear axle. It was annoying, because it meant I had to save for a new one, but at least he contributed towards it.

Almost worse than that, though, was the fact that the headmaster came to see what the kerfuffle was all about. It was hardly surprising. My kart was a racing two-stroke. No silencer. And the din was like a sudden assault by a squadron of angry android bees. Distinctly unimpressed, the head banned me from bringing it back to school. As it turned out, it didn’t matter; I would not be returning for another term.

There’s another story that Jeremy tells journalists. He says there were two pupils expelled from Repton in the 1970s: he was one, and I was the other …

Which brings me to …

CHAPTER 4

Coming up to my O-levels (GCSEs in today’s language), I shuffled in to see a careers advisor, who cast a disinterested eye over my mock results, coughed and then suggested I might like to pursue History, English and Art at further education. I thanked him for his time and left.

Needless to say, I had different plans. Working on my kart had taught me two things: first, that I probably wasn’t cut out to be a driver, because despite my best efforts, not to mention my various mechanical enhancements, the combination of me and kart just wasn’t that fast.

And second, it didn’t matter that I wasn’t cut out to be a driver, because although I enjoyed driving the kart it wasn’t where my true interest lay. What I really wanted to do – what I spent time thinking about, and what I thought I might conceivably be quite good at – was car design, making racing cars go faster.

So, much to my father’s relief, as the school fees were hefty, I decided to leave Repton for an OND course, equivalent to A-levels, at the Warwickshire College of Further Education in Leamington Spa.

I couldn’t wait. At Repton I’d been caught drinking in the local Burton-on-Trent pubs, which had earned me a troublemaker reputation that I was in no particular hurry to discard. My attitude to the school ranged from ambivalence all the way to apathy (with an occasional touch of anarchy) and the feeling was entirely mutual. We were never destined to part on good terms anyway. And so it proved.