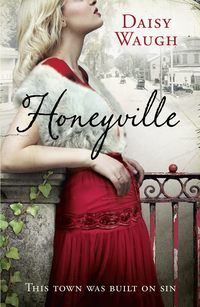

Honeyville

Lawrence O’Neill glanced up, looked the two of us up and down. He nodded politely at me – an acknowledgement of what had passed between us – before letting his bright blue eyes rest more warmly upon Inez. Slowly, he laid the gun on the table and stood up. There were sweat stains around the armpits of his shirt and waistcoat, and his chin was unshaven.

‘Well, well,’ he said, lifting the counter flap and stepping through. Inez, hardly five feet tall, looked like a child beside him. Or he looked like a giant. Either way, I thought they looked faintly ridiculous together. But it seemed not to bother them. On the contrary, the attraction between them was intense and obvious. I glanced at the boy, Cody. He was staring at them, with his mouth hanging open. ‘Just look here what the cat brought in,’ O’Neill said softly. ‘Tell me. How’s your head today, missie? It was fairly swimming the last time I saw you.’

‘Oh, it’s fine,’ Inez said. And then nothing. Silence. I’d never before heard her make such a short statement. It was a struggle not to giggle.

There was no window in the front office and no one had troubled to switch on the counter lamp, so the only light in the room came from the open door behind us. O’Neill’s face was bathed in afternoon sunlight, and the pleasure in his brilliant blue eyes burned bright for all to see. Inez’s facial expression, her back to the door, was impossible to read. Not that anyone needed to. Good God – she was squirming with it! She could hardly stand straight.

‘I didn’t think you’d be back,’ he said after a pause. ‘Thought you’d be chicken … But you’ve come to see how the other half lives, have you?’

‘I certainly have,’ she said.

He exhaled – something close to a laugh. His lively eyes fixed on her as she wriggled and swayed. ‘I’ll make a revolutionary of you yet, my friend.’

‘Oh! I doubt it very much, Mr O’Neill.’ It sounded pert. ‘I only long for the day my little town is peaceful again.’

‘Peace first, fairness some other time, huh? Isn’t that how it should be?’

She bridled, uncertain if he was teasing. ‘No! Yes. Perhaps … What I mean to say …’ I might have told her, except I thought it was obvious: politics wasn’t a teasing matter, not for the likes of Lawrence O’Neill. Not for the likes of anyone in Trinidad, that summer. ‘What I mean to say is, that Trinidad used to be a nice place to be …’

‘I’ll just bet,’ he said. ‘A woman like you has a lot to lose. Why in the world would you want to change things?’

‘Well, I didn’t say things shouldn’t change. Maybe they should … I only remarked that anarchy, socialism … all these sort of things we read about … and then you Union men coming in from out of town, stirring up the workers for your own political ends … it doesn’t strike me as a fair way of going about things either. So. Please. If you wouldn’t mind. Don’t insult me and I won’t insult you.’

He blinked but said nothing.

‘I have come here because you offered to show me round one of the company towns,’ she continued. ‘To educate me. Well, here I am. Very interested to see what you have to show me. Will you drive us? Or shall I?’ She indicated the beanpole boy. He was leaning his sharp elbows on the counter, still gawking at her. ‘Your young friend here said you were headed to Forbes today. So will you take us there or won’t you?’

He took a moment to think about it, and shook his head. ‘It’s dangerous,’ he said abruptly. ‘I was drunk. You should probably go home.’

‘Of course it’s dangerous!’ I think she stamped her foot. ‘If it weren’t dangerous I would have driven out there on my own. You said you’d take me, Lawrence O’Neill. Are you going back on your promise?’

Another pause. This one seemed endless. The three of us watched and waited.

‘Well, missie,’ he said at last, ‘if you’re certain. But I’m not taking you any place in that hat.’

Her hands sprung to defend it – the very hat she had bought for the occasion, and from which she had, last night, already removed the garland of silk flowers. ‘But I have to wear a hat!’ she cried. ‘I don’t have another. Not with me. What’s wrong with this hat in any case?’

‘It’s a very fetching hat, I dare say, if you’re drinking tea with the King of England. Why don’t you wear Dora’s hat?’ he said. ‘It’s simpler. Better. You won’t look like the laughing stock.’ He returned to the other side of the counter, picked up the gun he’d been cleaning, slipped a couple of shots inside and snapped it shut. ‘Well?’ he said, looking back at her, the loaded gun hanging by his side. ‘Are you coming or aren’t you?’

‘But I can’t take Dora’s hat!’

‘Sure you can.’

‘What about Dora?’

‘Sorry. But I ain’t taking Dora.’

‘What?’ She looked at me, aghast. ‘Dora?’

I shrugged. I wasn’t going to put up a fight. Everything I needed from the camps (and more) came to me at Plum Street. I was happy to leave the rest to my imagination.

‘Of course you’re taking Dora!’ Inez said. ‘Why wouldn’t you take Dora?’

‘Hookers ain’t allowed in. They’re strictly forbidden.’ His blue eyes glanced at me with a smile, not unfriendly. ‘The company guards’ll spot her in a jiffy.’

‘Well. I am not going without Dora. Certainly not!’

‘Well, I ain’t going with her.’

‘Dora?’ she turned to me, rather pitifully. ‘Darling? Don’t you want to come with us?’

‘Heck. It’s all the same to me,’ I said.

‘No but really,’ she said again. ‘I’m not going without Dora.’ It sounded less adamant this time.

‘What’s that, missie?’ he teased her. ‘Are you afraid?’

‘You bet I am,’ she said.

He laughed. ‘Don’t be chicken. I’ll make it interesting …’

I felt a stirring of responsibility. She was a grown woman, yes, but a terribly naive one and I had introduced the two of them. ‘I don’t think you shall go, Inez,’ I told her. ‘It’s dangerous out in the towns. Feelings are running so high.’

‘If anyone tells me again that it’s dangerous!’ she said. ‘I know it’s dangerous. And please won’t you come, Dora?’ She turned to Lawrence. ‘Won’t you please let her come?’ But by then I think we all knew the answer. Inez had already begun to unpin her hat.

We exchanged hats, and they set off together. ‘You look after yourself,’ I said to Inez as she climbed into the back of the Union auto and tucked herself out of view. ‘Come and see me tomorrow if you can – and bring me back my hat!’

‘I’ll come and tell you all about it! My new life as a Union organizer …’ She giggled, waiting for O’Neill to start the engine. ‘Don’t you dare tell Aunt Philippa!’

I smiled and waved, and wondered when she imagined I was likely to do that.

8

There was a back door to the house that the girls were supposed to use when we were off duty, opening onto a narrow servants’ stairway (the contrast between it and the plush richness of the front of house was almost comical). The stairway led directly up to the second floor, where I had my private rooms: a parlour, in which to entertain my clients after we had departed the ballroom, with bedroom, dressing room and bathroom leading off it. They formed, by necessity (as all the girls’ rooms did), an oasis of apparent privacy. As Inez knew from her vist the other day, it would have been a simple business for her to slip in and out of the building without meeting anyone. Even so, she didn’t come. I waited for almost a week, until finally I was concerned enough for her welfare that I called in at the Union offices to ask after her.

Lawrence wasn’t there. He’d been summoned to Denver that morning. I asked Cody (the bony lad) if he’d seen Inez recently, and he laughed.

‘She’s in here most the time,’ he said.

I was rather hurt to hear it, which surprised me. I left him with a sullen message for her, asking for the return of my hat, and trudged back home through the hot streets, feeling glum and slightly foolish.

She was sitting on a wall on the corner of Plum Street, tucked into the side of our imposing parlour-house porch, waiting for me, swinging her feet in the sunshine.

‘There you are!’ she cried, leaping off the wall and coming towards me. ‘I thought you would never come home! Where have you been? I have so much to tell you. So much! First about the camp. And then about Lawrence. You realize, don’t you, that I’m in love. At last, Dora! And I have you to thank for it.’

‘In love?’ I repeated, a touch sourly. ‘Well, goodness me!’

‘Absolutely in love. Of course I am in love. And by the way, if that’s you “acting surprised”, then you need to work on your acting skills, darling. You look just the same as if I had said to you: after night comes day. Was it really so predictable?’

In the face of such excellent cheer it was, of course, impossible to remain chilly for long. I said: ‘Well. You look very happy, Inez.’

‘Because I am!’

‘He seems like a good man,’ I said pleasantly, though in truth I’d not given it much thought.

‘Oh he’s awfully good,’ she replied. And she smirked and blushed and giggled. And wriggled and writhed.

‘Oh …’ I said slowly, examining her. ‘Oh my …’

‘What?’ she said. ‘What, Dora? Why are you looking at me like that?’ Her face and neck had turned quite purple.

‘You fucked, didn’t you?’

She emitted a feeble, miniature gasp, something be- tween outrage and delight.

‘You’re a fallen woman!’ I laughed. ‘Well well … And welcome to the club!’

‘What? Shh! Silence! For heck’s sake, Dora!’ She peered frantically up and down the empty street.

‘Hey – no one’s likely to be terribly scandalized round here,’ I said.

‘Oh God. There is so much I need to tell you,’ she said. ‘Can’t we please just go inside?’

As we climbed up the back stairs to my rooms, I put a finger to my lips. I didn’t want to have to introduce her to Phoebe, who would doubtless have invented a rule on the spot to prevent Inez from staying. Inez nodded her understanding, and made a show of dropping her voice to a whisper, but whispering wasn’t a skill she had mastered. ‘You must teach me all the precautions, Dora,’ she announced as we paused on the landing outside my door. ‘And then we have our project to set in motion. Have you forgotten?’

Inez’s project: to rescue me from my life of sin. I had not forgotten it, though I was unwilling to admit that too easily. She and I had discussed our ‘project’ when she first visited Plum Street after our hat shopping trip, and though in my heart perhaps I always knew it was preposterous, it gave me hope because I was lonely; it gave Inez hope, because she was a woman who needed a project. It gave us something to do together. And I had been quietly stewing on its possibilities all week.

(It was in fact a very simple plan, requiring above all that the nice ladies of Trinidad conformed to expectation, and etiquette, and failed to recognize my face. If I dressed demurely and spoke – this had been Inez’s brainwave – with an Italian accent, ‘the ladies won’t have the faintest idea who you really are. No one in Trinidad knows anything about Italy,’ she had said. ‘Or about anything else, come to think of it. You only need to throw out a few names. Michelangelo, Botticelli – oh gosh. That’ll do. And they’ll fall at your feet. Trust me.’)

I asked Kitty to send up lemonade and we stretched out in my small, overstuffed sitting room, taking one sweaty, silk-swaddled couch each, on either side of my empty hearth. I opened the window, to catch what small breeze there was. First, we talked about Lawrence.

She was smitten. ‘But you mustn’t tell Aunt Philippa,’ she kept repeating.

‘For heaven’s sake,’ I said at last, ‘I don’t know Aunt Philippa. And even if I did … But she must have guessed something’s up, hasn’t she?’

‘Aunt Philippa? Oh, gosh no,’ she said, waving the suggestion aside – and it struck me what a strange mix she was. Her childlike openness was so fresh and natural and disarming, and yet she possessed an equally fresh and natural – artless – talent and willingness to deceive, if not Aunt Philippa, then (should our project go ahead) all the gentlewomen of Trinidad. It was so instinctive, so pragmatic – I don’t believe any judgement of it even crossed her mind. I rather envied her the freedom.

She continued, forgetting Aunt Philippa: ‘Lawrence took me to a fleapit,’ she said. ‘Well, no, it wasn’t a fleapit. It was a perfectly pleasant hotel. Out in Walsenburg, because we couldn’t do it in Trinidad. And he signed us in as a married couple. I thought I would die of shame. But then. Gosh, darn it Dora, I can hardly believe you’ve kept it to yourself all this time!’

I felt a prickle of unease. Had he told her of the night we spent together? But it was nothing – a mere transaction. Surely not. ‘Kept what to myself?’ I asked.

‘What? Why, sex of course!’

I laughed. ‘Believe me. You can get tired of it.’

‘Impossible!’

‘Trust me.’

She uttered a sound, a sort of gurgle, a mix of mirth, smugness, wonder, lust …’Well perhaps. In your line of business, maybe you can. And I guess not everyone can be as pleasing as Lawrence. But anyway you must tell me all your tricks – will you? You must have hundreds of clever tricks.’

‘I’ll tell you plenty of tricks so you don’t conceive his child,’ I said. ‘And I’ll tell you what and how and where to go if my tricks let you down.’

‘No – I mean yes. Of course, you must. And thank heavens to have a friend like you. But I meant the other tricks – you know …’ She looked coy. ‘The filthy ones. So he doesn’t wander. So that I please him absolutely and completely and he never looks at any other woman ever again.’

I managed not to smile. ‘I shouldn’t fuss on that count,’ I replied. ‘If he’s going to wander, he’s going to wander. The only trick I’ve got for you is to darn well please yourself, Inez. Please yourself, and the rest will likely follow. Probably. Sometimes. Or at least for a while. Enjoy yourself.’

Inez nodded very solemnly, as if I were divulging to her the one and only true secret of the universe, and it occurred to me that, of all women, Inez hardly needed the advice. She pleased herself instinctively and, by way of pleasing herself, instinctively pleased others. And by way of pleasing others, pleased herself. She was warm and bold and open-hearted enough that the two were generally one and the same.

Not for the first time, I reflected what an excellent hooker she might have made, if she had been born in different circumstances. I wondered if it would amuse her for me to tell her so – and decided against it.

‘But you haven’t even asked me about the company towns, Dora,’ she said suddenly. ‘And the dreadful plight of those poor miners. You really should have come to Forbes with me! You can’t imagine … Did you even know …’

Of course I knew. Coal company managers and Union agitators – they all passed through my rooms. Miners too, sometimes, when they got lucky in the gambling halls. If what you wanted was a balanced view of the hatred and distrust that consumed our corner of the prairie, I was surely best placed to provide it. There wasn’t much I didn’t know about the misery of the company towns, where miners lived and worked and raised their families, cut off from the rest of the world. It was why (aside of course from the fact that hookers were forbidden) I never had much inclination to go visit them for myself.

Of course I knew – but I was surprised by how much she knew now and what a turnaround had occurred in her thinking since last I saw her: the transformative effect, I reflected, of a few hours at Forbes, and a few hours in bed with Lawrence O’Neill. She proceeded to lecture me, with the convert’s passion and certainty, about the collapsing, exploding tunnels, and the miners killed and maimed … and the long hours, the late pay, the poverty, the danger and the darkness. ‘The companies don’t employ the workers,’ she said. ‘They own them: their homes, their schools, their doctors, even their currency – and then they keep the prices so high in the company stores, the poor miners can afford to buy only half of what they could afford to buy in town …’

When she seemed to have finished, I assured her that I agreed. ‘They treat the men like animals,’ I said. ‘It’s a disgrace.’

‘On the contrary!’ cried Inez. ‘They treat the animals better. It matters to them if a mule is lame. It still has to be fed. If a mule is blown up in one of their careless explosions, that is so many dollars wasted.’ I could hear Lawrence’s voice and turn of phrase in everything she uttered. He had recited the same speech to me too. ‘But if a man is maimed. If a tunnel collapses on him, and he is maimed and blinded or killed …’

Yes, yes.

‘Well – never mind he has five children to feed and a wife with another on the way – he is worthless to them! If he can’t dig coal out of the rock at the same rate as the other man – he might just as well be dead. And then, Dora, tell me, what is to become of him and his wife and children then? It’s all very well for the company to boast of its schools and its pleasant houses, and the little back yards with chickens and so on – but what becomes of a man the moment he is of no use to the company? What then?’

I sighed. Couldn’t help myself. And wished that Lawrence were back in town so the two could rant at one another. ‘It is a wicked and unfair world, Inez.’

‘Yes it is, Dora.’

‘I’m sorry you have had to wake up to it.’

She had opened her mouth to speak but she closed it again at once. She smiled, shamefaced. ‘It’s true. I am rather late …’

‘Better late than never.’

A graceful pause. But Inez couldn’t stay subdued – or shamefaced – for long. ‘By the way, darling, I was thinking about your wardrobe,’ she said. ‘For our project I mean, of course.’ She nodded at the door that opened into my dressing room. ‘I thought it might be fun to look through your clothes and decide what you should wear, so as to look suitable. Something sober and not at all … you know. If you look too flashy they won’t take to you and our entire project will be lost.’

Inez had taken to heart my wish to set up a singing school. I dare say that even after her nights of sin and sexual awakening with Lawrence, she could never quite accept what it was I did for a living. Ladies of leisure, I note, seem to be born with reforming zeal deep in their blood and bones. No matter what, they encounter a woman like me – a woman who isn’t like them – and they feel the need to change her. Added to which, with Lawrence away, Inez was bored. I think it amused her to conjure such a mischievous plan – especially one that might simultaneously bring her new friend so much happiness. In any case, Inez was determined to rescue me.

And I was touched – more than touched. And even if, in the cold light of day, I thought her project was a little preposterous; even if she and I had only half thought it through; the mere fact of there being one – of my having a friend who cared enough to want to conjure it for me – was a wonderful thing. Inez was determined to rescue me and – whether I needed it or not; whether she could rescue me or not – I felt blessed.

9

The Project? Inez was going to use her connections to help me start up a singing school in town so that I could leave my life at Plum Street behind and become a respectable woman again.

The plan? Was this:

I was to be introduced to the Trinidad elite as an Italian from Verona whom Inez had found, searching for books about Italian opera in the Carnegie library.

‘Brilliant, no?’ Inez giggled (the opera idea having been hers). ‘An excellent touch for added veracity. There you were, not looking for ten-cent romantic novels like every other lady in Trinidad, but seeking out improving books about Italian opera! In fact, Dora, why don’t we say you have written one? In Italian? You could offer to send for it – pretend to have one sent all the way from Verona. And then, once you’re properly established, we can say it was lost, and pretend we are sending for another … and then another. Wouldn’t that be too funny? They’d be so impressed.’

The idea had been that I should give a recital at the Ladies’ Music Club, which convened at 4 p.m., according to Inez, on the third Tuesday of every month. Each month, just like the Ladies’ Plant Appreciation Club, the Ladies’ Historical Club, the Ladies’ Travel Club and numerous other clubs, it took place at the home of a different lady, whose task it was to provide both refreshment and entertainment. Inez said it was her Aunt Philippa’s turn to be hostess:

‘Or at any rate, if it isn’t, then it ought to be. I shall make it happen. She has the only decent piano in Trinidad, so they really oughtn’t to complain. Assuming,’ she added as an afterthought, ‘you know how to play it?’

‘Of course,’ I said, indicating my beloved harpsichord, sweltering beneath a velvet throw and sundry decorative knick-knacks in the corner of the room.

‘Good.’ She glanced at it. ‘Oh, is that what it is? How adorable! The ladies love to go to Aunt Philippa’s anyway,’ she added. ‘Because of the honeycake. We have the best honeycake, and Aunt Philippa swears she will take the cook’s recipe with her to her grave. Which is horribly mean of her, I always think. Never mind. We need to decide what you will sing – something God-ish, definitely. And then something romantic.’

‘I don’t have an operatic voice, Inez. It’s more of a dance-hall, vaudeville type of singing.’

‘They won’t know the difference. Believe me, they won’t have the slightest idea. We need to choose you some clothes. And then we can tell all the ladies how lucky they are that you’re setting up in town as their singing instructress. And I shall make a great performance about how much you have helped me with my singing – and sure as night follows day, the ladies will follow me. And it’ll be perfect! We can put on a show at the theatre in the New Year, and le tout Trinidad will turn out. Et voilà! Goodbye Rotten Plum Street. Hello … Well. Hello, somewhere else! The best plans are always the simplest ones.’

‘You honestly don’t suppose that they will recognize me?’ I asked her. ‘Because I’m certain I shall recognize most of them. If not their names, then their faces.’

‘Absolutely not!’ she said, leaping up from my small couch. ‘We can make your hair as dowdy as can be – and we can make sure you only wear the plainest clothes – and if you don’t have anything suitably drab in your wardrobe, we’ll go to Jamieson’s together and pick something out! So. Are you going to show me your dressing room or aren’t you? For heaven’s sake, we only have a week or so to prepare. Do let’s get on with it!’

10

Lawrence was out of town for several days afterwards, and Inez dedicated herself to our project. On the morning of the event, she arrived at Rotten Plum Street (as she now referred to it) unannounced. She rushed up the back stairs and burst into my small sitting room without knocking. ‘I have thought of everything!’ she said, dropping herself onto the nearest couch.

I was alone at my harpsichord, playing to calm my nerves. Her entrance made me jump. ‘Inez!’ I said. ‘You can’t simply burst in like this. God knows – what if I had been with someone?’

She looked around the small room. ‘But you’re not,’ she said. ‘Besides, it’s ten in the morning – and didn’t you tell me you never allowed them to stay the night?’

‘Even so …’

‘It’s horribly airless in here, Dora. Why don’t you open a window?’ She stood up again, and went to open it herself, impatiently pushing aside the knick-knacks and ornaments on the sill. ‘You should throw out half this junk. What do you keep it for?’

‘They’re gifts,’ I told her. ‘Believe me, I long to get rid of them. But I can’t. Otherwise …’