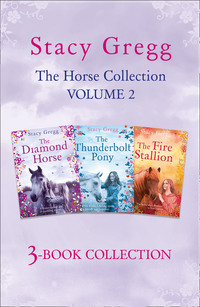

The Stacy Gregg 3-book Horse Collection: Volume 2

The tigers seemed to sense Anna’s kindred nature. Veronika and Valery, named so by Anna, lay down on the floor of their golden prison, barely twitching their tails while she lay on her belly on the other side of the bars. They were utterly content in each other’s company. Unlike the bears, the tigers also seemed to be well matched. Anna could see from the way they rubbed against one another and gave each other playful cuffs with their enormous paws that they had a happy relationship.

It was easy to tell them apart. The male tiger was far larger and his face was broader. The female was smooth and sleek with a distinctly regal beauty. The black stripes of her arched eyebrows reminded Anna of the kohl brows her mother drew on as part of her make-up for dinner parties.

She had never told her mother about what had happened the night she tried on the necklace. She had put the black diamond hastily back in its case, and since then the stone had remained there. The next time it was brought out, her mother would place it round Anna’s neck herself. However, that moment would not bring Anna the joy that she expected. Instead, it was the worst moment of her life.

Winter had set in at the Khrenovsky estate. Snow covered the topiary on the palace lawn and the gilt cages were draped in heavy tarpaulins to provide some shelter for the animals within. The bears and the foxes were in hibernation. The tigers, who lived snowbound for most of the year in the wild, took it in their stride. Inside the palace, the exotic creatures were kept warm by the roaring stoves, the fires stoked constantly.

“We must bundle you up,” the Countess would tell Anna as she wrapped her in woollens and furs before she was allowed outside, “otherwise you shall fall ill.”

However, it was not Anna but the Countess who succumbed to sickness. In the week before Anna’s tenth birthday her mother developed a raging fever that drove her to bed. By the third day, when the Countess was still bedridden, Anna began to worry.

“We should send for the doctors,” she told Ivan. “Mama is getting worse. It might be pneumonia.”

“So you have diagnosed her yourself?” her older brother sneered. “Well, we don’t need the doctors now, do we?”

“Ivan!” Anna said. “This is serious.”

Ivan rolled his eyes. “The snowfall is too heavy – the doctors will never come in this weather. Let the housemaids do some work for once and care for her.”

Anna couldn’t help but think that her brother secretly delighted in their mother’s illness. With their father away at sea fighting the Turks, Ivan considered himself in charge. With the Countess confined to her room and Katia in constant attendance on her, Ivan demanded the kitchen should throw away the dinner they had made and produce his favourite meatballs instead. When the food came he pushed aside his cutlery and ate greedily with his hands, smearing grease on his shirt front.

“Come on, Anna,” he taunted her. “Let’s have some fun for once. How about a swordfight?”

“No, thanks.” Anna tried to leave the table.

“Where do you think you are going?” Ivan’s mood shifted suddenly from playful to threatening. “If you won’t play, you can at least stay and keep me company.”

And so she was forced to sit in her chair while he grabbed his sabre and leapt around on the dining-room table, skidding in his jackboots on the polished wood, kicking plates and glasses aside so that they crashed to the floor, laughing like a madman.

Anna watched her brother anxiously and felt gnawing panic rise in her. While Ivan played master, their mother’s health was growing worse by the hour.

“We need to send for doctors,” Anna tried insisting again.

“All right!” Ivan groaned. “Only will you stop complaining? You are giving me a sore head.”

By the time the physicians arrived the situation was grave.

“Send a messenger to your father, Count Orlov,” Anna overheard the head physician telling Ivan. “He must return immediately if he wants to see his wife alive.”

As the Countess’s condition deteriorated Katia was a constant presence at her mistress’s side, mopping the Countess’s brow and holding her hand to ease the pain.

It was Katia who came to Anna, her face ashen, and told her that her mother was asking for her. Anna found herself walking as if in a dream, towards her mother’s chambers. The Countess looked so thin and frail from her illness, but still beautiful.

“Is that you, milochka?” Anna’s mother raised her head from the pillow and put out her hand to clasp her daughter’s fingers.

“It’s me, Mama,” Anna said, her voice trembling.

The Countess smiled. “Dearest one. Come here and take my hand.”

Anna was surprised by the coldness of her mother’s fingers, like icicles against her skin.

“Milochka,” her mother instructed. “I need you to do something for me.”

“Anything, Mama.”

“My black diamond necklace. You will find it in the top drawer of my dresser. Bring it to me?”

Anna did as her mother instructed, carrying over the necklace in its velvet case and placing it on the bedside.

“Open the box,” the Countess instructed.

Anna carefully prised it open and the Countess reached in and took out the priceless jewel. “The Orlov Diamond,” she said, “has been in our family for many centuries. My mother gave it to me and her mother before her …” She turned to Anna.

“And now milochka, it will be yours.”

Anna’s eyes filled with tears. “No, Mama, I do not want it any more.”

“Anna.” Her mother’s voice was gentle. “Please, let me see how it looks on you.”

Not knowing what else to do, Anna bowed her head in obedience as the Countess weakly raised herself up off the pillows to clasp the necklace round her daughter’s pale neck.

“So beautiful!” the Countess breathed. And then she added, “But it is not the first time you have worn it, is it? That night in my room. You tried it on.”

Anna nodded. “I did.”

“So you already know that this is no ordinary necklace.” The Countess nodded wisely. “Well, know this too, dear one. You must never seek to understand its power, and do not try to control it. Past and present and future all lie within this necklace, but it is the stone that decides what you will see.”

The Countess looked very sad, and then gripped her daughter’s hand even more tightly. “Anna,” the Countess said. “Your father …”

“He is coming, Mama,” Anna tried to reassure her. “We have sent for him, he is on his way!”

The Countess shook her head. “No, my dear one, I know he is not. He will not come for me.” The Countess’s expression was dark. “I know your brother too. He is so different from you, Anna. I wonder how it is that I could have raised two children, one so lovely and one so …” the Countess drew a sharp breath and began to cough. Anna had to help her sit up, adjusting the pillows so that she could breathe again.

“Look to Katia,” the Countess whispered the words. “Katia will care for you. If you are ever in any doubt about what to do, go to her. You can trust her with your life …”

“Mama …” The tears rolled down Anna’s cheeks. “Please do not talk like this. You are going to be fine, you will get well again …”

It was Katia who found them.

Anna was slumped and sobbing, still clutching her mother’s cool hand. Katia raised the white sheet of death over the Countess’s face and hugged and comforted Anna. Ivan was nowhere to be found.

“I went hunting,” he told Anna when she asked where he had been. “It would have made no difference if I had been here, would it? It was always you that she loved.”

Anna was shocked. “Do you really think Mama didn’t love you?”

Ivan laughed harshly. “What do I care? Anyway it was a good hunt. I bagged a deer. So don’t try and make me feel guilty about it.”

“You do not care that she died without you or father beside her?” Anna said.

“Our father is Admiral Lord Commander of the Black Sea,” Ivan sniffed. “He does not run to his wife’s bedside like a weakling when there is a war to be won.”

With no mother and no sign of their father’s return, Ivan took it upon himself to rule the Khrenovsky estate. He started wearing the Count’s greatcoat inside the house, even though he must have been baking hot. The huge garment swamped his lean thirteen-year-old frame. He would stalk the corridors, laughing to himself and barking ridiculous orders at the serfs. And the servants began to call him “Ivan the Terrible” behind his back. As for Anna, she avoided her brother as best she could, spending most of her time down at the stables with the horses and Vasily. It was there that she heard the news that her father was finally coming home.

The war, in fact, had been over for some time. Count Orlov could have sailed home several months ago, but instead had delayed his return by deciding to travel overland. The reason for his change of plans was a horse.

“His name is Smetanka,” Vasily told Anna. “It has taken his men almost a year to walk him through the mountains from Turkey into Russia. The Count joined them on the coast of the Black Sea and he is personally escorting the horse on the final leg of the journey home.”

“My father didn’t come home to my mother because he was walking a horse?”

Vasily tried to soften the blow. “Smetanka is not ordinary horse. He is purebred Arabian stallion. They say he cost Count Orlov 60,000 roubles!”

The price of Count Orlov’s Arabian was the talk of the palace. At the stables the grooms spoke of nothing else. “What kind of horse could be worth such money?” Yuri, the head groom, could not disguise his scorn. “I could buy a hundred of the best stallions in Russia for that!”

“If he is truly great stallion he will be worth it,” Vasily replied.

“Did I ask your opinion?” Yuri had snapped back.

Yuri resented the junior groom’s gift with horses and yet he could not get rid of him. Vasily was the most talented horseman in the Count’s stables. So Yuri made him work twice as hard as the rest. It was Vasily alone whom the head groom charged with the task of preparing the stable for the Arabian’s arrival. And Vasily who was sent out to meet Count Orlov’s party at the gates of the estate.

Anna went with him, desperate to see this “very special” horse that had kept her father away during their darkest days. For hours she stood at Vasily’s side as the snow fell, and then finally when the night was drawing in, she saw riders in the distance. There were about a dozen men on horseback. Count Orlov rode at the head of the party and when Anna saw the horse that her father sat astride she was bitterly disappointed.

Smetanka looked so plain! A chestnut with a narrow chest, Roman nose and stocky limbs “He does not look like he is worth a hundred roubles even!” Anna muttered.

“Oh no, Lady Anna.” Vasily shook his head. “That horse, he is not Smetanka! Look! The grey stallion, in the middle with no rider, that is him …”

The Count was not foolish enough to ride his valuable new acquisition on treacherous roads. Instead, he had reined Smetanka in the midst of his riders, surrounded by a cluster of mounted soldiers. The ruse was pointless, however, because alongside the soldiers’ ordinary, thickset carthorses, Smetanka’s singular, exquisite beauty stood out like a shining star, so bright it eclipsed them all.

He was the colour of highly polished silver and his coat looked as if it had been buffed to the sheen of precious metal. His neck arched like a fountain, and his limbs were so fine and delicate it seemed impossible that those slender legs had journeyed over the mountainous terrain of Turkey. And yet even though he had been travelling for the better part of a year, Smetanka strutted out with the flamboyance of a dancer, as if he were sashaying to some unheard music, sinew and muscle rippling under his glistening coat.

Just as she had been instantly intoxicated by the sight of the Siberian tigers, Anna now found herself falling in love all over again. It was not just the physical beauty of the stallion that drew her, but something deeper. His dark eyes spoke to her deeply and she was reminded of the way she had felt gazing into the black teardrop diamond for the first time.

Instinctively she felt for the necklace at her throat, grasping the stone tight in her fingers. It was a reflex, a habit she had developed to soothe herself ever since her mother passed away. Had it really been a whole month since her death? Anna had been so desperately lonely without her. She had not seen her father in almost a year.

The horses shook their manes, bits clanking in their mouths. They were snorting and blowing from their long journey. Count Orlov, his cape dusted with snow, fur hat pulled down low across his brow, dismounted from the narrow-chested chestnut and walked towards his daughter. For a long while, he said nothing at all, and Anna did not dare to speak. Any words she might have wanted to say were knotted tight in her throat.

“You have grown,” Count Orlov said, without any emotion in his voice. “And yet, with my blood I would have expected you to be taller still.”

A look of annoyance crossed his face. “Why are you here, child? And where is my son?”

It took Anna a moment to find a reply.

“My brother, Father?”

The Count gritted his teeth. “Yes, your brother. Where is he?”

“Ivan is at the palace, Father.”

Count Orlov cast a glance at Vasily. “Take the Arab to the stables. See that he is well looked-after. It is colder here than he is accustomed to.” And then, without another word to Anna, the Count remounted his horse. He set off at a gallop, his men closing ranks behind him, heading for Khrenovsky Palace, his home and his son, the only child who mattered.

CHAPTER 4

Boris and Igor

Hot-blooded Smetanka had not been bred to survive the bitter cold of a Russian winter. As the weather became bleak and the coarse carthorses grew thick, shaggy fur, the Arabian remained fine-coated, shivering and miserable. When the snowdrifts gathered outside his stall, Vasily piled the horse with layers of rugs to try to keep him warm. All the same, the cold chilled Smetanka’s bones, and the stallion rapidly lost condition. By February he was reduced to nothing but rib and sinew.

“I worry for him,” Vasily confided to Anna. “He is so thin and always anxious. When I arrive at the stables before dawn he is always at the door of his stall. I have not once seen him sleep.”

For a few hours each day, Vasily would take the stallion out of his stall and let him loose in the small field near the stables. This was the time that Anna most looked forward to. She loved to see the Arabian in motion, the flamboyance of his high-stepping trot and the smoothness of his canter. Smetanka, unaccustomed to the snow, found the cold drifts around his legs intolerable. He elevated himself with every stride, as if he could not bear to make contact with the ground for more than a split second. To gallop with his tail held erect and his head high was the only respite for poor, unhappy Smetanka.

“He hates it here,” Anna told Vasily. “I can sense the homesickness in him.”

Vasily did not argue. “Lady Anna, his blood is high born, bred for the desert.” He shrugged. “Heat and dust are all he has known his whole life. To be brought here to the bleakness and the cold, it is no wonder he is so unhappy.”

Yuri would not listen when Vasily tried to tell him how depressed Smetanka had become.

“Oh very sad, it is,” he mocked. “Poor horse, waited on hand and foot. I should be so lucky to be priceless Arabian instead of worthless head groom!”

Yuri’s dislike of Smetanka only deepened when Count Orlov tasked his head groom with finding a potential mate for the prized stallion. Yuri began by parading a selection from the Count’s own stables for consideration. He was dismayed when Count Orlov rejected every single one of them.

“Inferior!” The Count waved them all away with a dismissive hand. “None of them are worthy of my stallion! Increase your efforts and widen your search!”

Next, Yuri sent his riders out to hunt for mares, first to farms around Moscow, and then the whole of Russia, but without success.

“You bring me another ugly cart-beast!” Count Orlov fumed. “I am trying to breed the best carriage horse in Russia and you, Yuri, bring me pig-slops as his bride!”

In the end, it was Count Orlov himself who found Smetanka’s perfect match. The mare’s name was Galina, and she was a carriage horse from St Petersburg. Dark brown with a very pretty face and four white socks, Galina was descended from the Empress’s carriage stallion.

“She has strong legs and a powerful chest,” Count Orlov assessed. “Let us hope she will pass on these traits when her blood mingles with Smetanka’s.”

The merging of bloodlines was an obsession for the Count. Anna was beginning to notice how often her father spoke of breeding, not just in his animals but in humans too. If he singled out a noble of the royal court to comment upon he would always note their “blood” and whether it was good or not. To the Count, the blood you carried inside you was of the utmost importance, as were your physical attributes. Anna, with her blonde hair, lithe limbs and pale ivory skin, could not help but resemble the Countess.

“Your mother was of excellent blood, descended from royalty,” Count Orlov had told Anna as they watched Yuri parading yet more unsuitable mares. Anna was surprised to hear him speak of her mother at all. From the moment of his return to Khrenovsky, Count Orlov had insisted that every trace of the Countess be removed from the palace. It was as if she had never existed. Her portraits were taken down from the walls and her room was cleared out. Anna had been devastated to discover that all of the Countess’s beautiful evening gowns had been disposed of, burned on a pyre. She would have so loved to keep them, so that one day she could wear them to grand balls in opulent palaces just as her mama had done. But Count Orlov made sure that nothing was left. The black diamond jewel which Anna wore at her neck was the only memento of her beloved mother.

***

As the icicles froze solid on the bare limbs of the trees it became clear that Galina was in foal. The tigers too, were expecting a cub. Anna was the one who saw the signs of pregnancy before anyone else. She noted how Veronika, the tigress, was so grumpy, snarling and growling at Valery for no good reason. Then the swell of the tiger’s waist confirmed it. There was a cub on the way.

Anna spent every minute she could with Veronika. She would set up camp on the lawn and Katia would ferry out her breakfast and lunch on a tray, only insisting that her young charge came back in at nightfall for dinner. Even Clarise gave in to Anna’s pleas and agreed to tutor her as she sat beside the cage – albeit shouting her instructions from the safety of the terrace – so that Anna could watch and wait for the baby tiger to be born.

One day Vasily came up to visit her and found Veronika pacing the bars while Anna pressed right up to them, stroking the plush fur of the gigantic cat as she swept by.

“Do you want to lose an arm?” he asked, horrified. “Pull your hand out! She is about to attack!”

The tigress was emitting a strange, deep growl. It sounded fearsome, but Anna knew better. “Listen! Do you hear that?” She smiled. “Veronika is purring to me!”

All the same, Vasily dragged her away from Veronika, enlisting Anna’s help down at the stables.

“Your father has ordered me to break in Smetanka so that the stallion can be ridden under saddle,” Vasily explained. “I need a lightweight rider to put on his back the first time.”

“Me?”

“You are a good size, Lady Anna.”

“But I have never broken a horse before,” Anna said.

“I have seen you ride every horse in this stable,” Vasily replied. “You have a good seat and kind hands. You are never afraid and I have never seen you fall. I think you will do.”

As they approached the stables, Anna’s stomach was tied in knots.

Smetanka fretted and stamped in the loose box as Vasily put on his saddle and bridle. Anna watched the stallion moving about restlessly and marvelled at his beauty. Smetanka could have been carved from marble. Anna stepped up to the horse, admiring the way his ears pricked in a curve so that the tips came in and almost touched. She delighted in the way his nostrils widened with excitement, taking snorty, anxious breaths. Instinctively she crouched down in front of him and put her face close to his muzzle, and then she breathed too, long and low, deep and slow breaths. Soon Smetanka’s breathing slowed down too until they were both calm.

Anna reached out her fingers to stroke the stallion’s beautiful dished nose. “Don’t be anxious,” she told him. “We are going to have fun together, you and I.”

Vasily led the horse out of the stables into the field beyond. The snow was falling lightly, and Smetanka shook his mane repeatedly.

“Do not ask too much of him today,” Vasily said to Anna. “Walk him perhaps, or trot a little, no more than that. It is his first time with a rider on his back.”

Anna raised her leg, signalling that she was ready, and Vasily took hold of her thigh and boosted her up.

Smetanka surged forward at the strange sensation of weight on his back, and he danced a little, but he did not buck or rear or try to run. When Anna took up the reins and began to steer him, guiding him with her hands and her legs, he soon understood what he was required to do. It was not long before she was walking him without Vasily at her side, and then trotting him. His paces floated above the ground as if he were lighter than the air itself!

“It is like riding a cloud!” she giggled.

Vasily frowned. “Be careful,” he warned her. “He is very powerful. That is enough for one day, I think. Slow him and bring him back to me.”

But Anna was having such fun on the horse that she was no longer listening. Smetanka was so biddable, so clever, and she felt so safe on him. She gave a quick pulse of her legs and cried out with delight as Smetanka responded by breaking into a canter. The fluid beauty of his stride suspended her and she could think of nothing else except the wonderful feeling of flying. For the first time since her mother’s death, she was happy.

Anna never wanted to come down again, but she knew that she could not ride Smetanka forever. Besides, Vasily was now shouting at her to halt. So eventually, she turned the magnificent stallion back to the stables and cantered him all the way until they were at the gates.

“He is amazing,” she told Vasily as she dismounted and passed him the reins.

“He is a great horse,” Vasily said. “And a very valuable one. You must listen to me next time, Lady Anna. Do not go racing off like that! 60,000 roubles and you treat him as if he is your riding pony!”

Never mind that Vasily was grouchy with her, Anna was elated by her ride. She made the long walk back to the palace, feeling the pleasant ache of her tired muscles. Katia had drawn a bath and laid out a dinner gown on her bed. After she had changed and brushed her hair, Anna went downstairs to the main dining room.

Since his return to the Khrenovsky estate, Count Orlov had seldom made time to have dinner with his children. In the grand dining room, at a table large enough to seat thirty guests, Anna and Ivan ate alone. Anna had given up trying to engage her brother in conversation at these dinners – usually he sat at the far end of the table and refused to speak to her. Today, however, when she entered the dining room, Ivan called out to her.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.