Tiflis stamp

They had lived together with Elizaveta Dmitrievna, nee Princess Orbeliani Dzhambakur-Orbeliani for almost 20 years. The Prince died in Geneva, but his will was to be buried in Kursk province, in the ancestral village of Ivanovo, which was fulfilled. [9]

As we can see, the biography of this remarkable man, his temperament and nature not only allowed him to win on the battlefield and resolutely implement the reforms, most daring for that time (including those in the postal service), but also to undertake the steps in his personal life, which none of his contemporaries would dare!

Prince A.I. Baryatinsky – a vicegerent and a reformer

Let’s go back to the state activity of the Prince, his role in the system of imperial power of that time. Personal correspondence of A. I. Baryatinsky and Emperor Alexander II provides a lot of information for understanding the reforms carried out at the time in the Caucasus. The letters of the considered period were included in the personal archive of Field Marshal, which after his death was handed to A.L.Zisserman, who wrote a large book on the life and work of Baryatinsky. [10]

After the revolution, the fate of the letters remained unknown. In 1966, an American researcher Alfred Rieber published a book, “The politics of autocracy”. The second part of the book is the above-mentioned letter, published retaining all the original features, including the French language. In his publication Rieber refers to the Archive of Russian and East European history and culture at Columbia University. [11]

The letters tell an interesting information about the relationship of Alexander II with Baryatinsky and are the source of information on the history of Russia’s foreign and domestic policies in the 1850—1860 and, above all, on the final stage of the Caucasian War.

Since the emperor and the vicegerent were close friends, their correspondence is personal in nature. This is evident by the way Alexander II refers to the Prince (“dear friend,” “my dear Baryatinsky”) as he passes the best wishes from his spouse and from the Empress Dowager (she died in 1860). When writing a letter in French the emperor addresses his interlocutor using polite “you”, but in Russian phrases he turns to friendly “you”.

The financial situation in the country was very difficult after the Crimean War. Alexander II constantly reminded his vicegerent about it, demanding a “wise economy” of funds and curtailment of expenses. Baryatinsky tried to do his best to fulfill this instruction of the monarch not only in military affairs but in the civilian affairs while ruling the region. Carrying out further reforms in the field of postal services he, as a vicegerent, set up a task in front of the management of the post office – to sort out the mess and to save the costs.

Unknown painter. Vicegerent in the Caucasus, Prince A.Baryatinsky.

The monarch approved the project of the military reforms and repeatedly reminded of the need to accelerate work on the drafting the civil part of the management restructuring, which included mail service.

Being an outstanding military commander and a great statesman, A. Baryatinsky understood that the development of communication was of great importance for the Caucasus region. Mail at that time was the only means of communication, and therefore its proper organization was a prerequisite of all planned and ongoing reforms. Without clearly-established postal service no successful military operations of the army as well as any civil transformation in the economy and social life were possible. Therefore, the vicegerent could not ignore the issues of reorganization of the post service in the Caucasus.

As it can be seen from the correspondence of Prince Baryatinsky and Emperor Alexander II, the vicegerent of the Caucasus had the most extensive powers granted to him by the law, and he had practically unlimited power of the tsar deputy in the region. Taking any decision on reorganization on the territory, trusted to hi, the vicegerent could always be sure of the support of the emperor, which was repeatedly used to solve serious financial and political issues. The Emperor used to write to him: “You decide yourself on the spot…” [12]

As soon as he was appointed a vicegerent, A.I.Baryatinsky had immediately taken the first steps to provide his full independence. On August 8, 1856, he filed a memorandum to Alexander II in which he asked to withdraw all the incomes and expenses on the Caucasus region from under the authority of the Ministry of Finance and give the vicegerent a complete freedom over them, as it was until 1840. Thus, in 16 days after his appointment the vicegerent of the Caucasus, Alexander Baryatinsky got free of the Minister’s of Finance patronage.

On April 25, 1857, the decree that regulated relations between the vicegerent of the Caucasus and the Senate was issued. Prince Baryatinsky received the right to suspend the execution of the decrees of the Senate in judicial, civil or criminal affairs in case of “local inconvenience, trouble or harm” for the Caucasus region. When the cases referring to the Caucasus came to the Senate, the Senate was deprived of the possibility to send them to the Ministry for consideration and could refer only to the vicegerent.

At the General Directorate of the vicegerent, Prince Baryatinsky established a Temporary department, where all the cases requiring new legislative measures on the issues pertaining to the different sections of the management and the development of well-being in the region were concentrated, and which was in charge of preparation and development of various projects. This department was also involved in the collection of “detailed and correct information about the status of the region, the progress made in the cases, the costs and other issues connecting with the administrative statistics of the vicariate.”

The painter A.O. Orlovsky. Troika. Military courier. 1812.

Vicar was given the highest supervision over the execution of laws by local institutions. All the offices and officials as well as individuals located in the Caucasus had to report to him. The vicegerent was the chief administrator of credits.

According to the law, the vicegerent had the right to expel any person from the region if such residence was recognized harmful. But they were not only individuals, who were expelled. After the victory over the mountaineers in the Caucasian war, the whole nations were expelled. The vicegerent was charged with supreme supervision of the Muslim clergy and the spiritual establishment. [13]

Expanding his reform efforts in the Caucasus Prince A.Baryatinsky immediately drew attention to the improvement of postal services in the region. A postal service at the time urgently demanded its radical change.

Chapter 2. Tiflis mail of the ХIХ century

Postal Service of the Caucasus in the second half of the nineteenth century

After the accession of Georgia to Russia in the first place it was scheduled to continue the construction of post tract from Mozdok to Tiflis with the length of 258 versts with the construction of ten stations to serve the postal rush on it and one post office in Tiflis. But those plans were hold back by the scarcity of funds allocated.

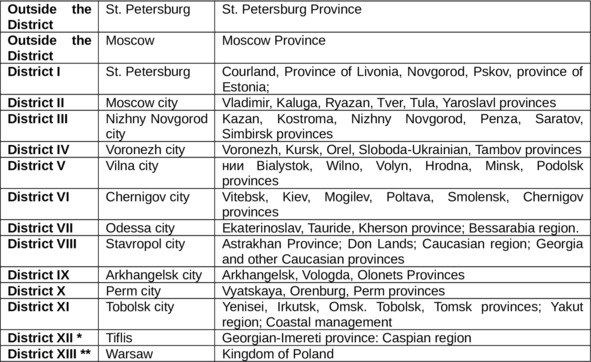

In 1830, to simplify and accelerate the movement of office correspondence, the Post Agency reorganized the Russian post offices. By the nominative Decree of Tsar Nicholas I to the Senate “On the new structure of the mail system” from October 22, 1830, the division of the territory of Russia into 11 postal districts was provided. (See. Table 1).

Five provincial post offices were canceled, and provincial, regional, border and foreign post offices had to report directly to the Postal Department. Georgia postal institutions were included in the postal district VIII.

The city of Stavropol was determined to be the seat of Postal Inspector of the district; one of his assistants had to reside in Tiflis to supervise the post offices of the Transcaucasian region. Tiflis post office was elevated to the rank of regional office with a staff of 12 people (4 sorters were added). The new “Regulation on the system of the postal unit” was put into operation since January 1, 1831.

Table 1. DIVISION of Russian territory into the postal districts in the first half of the nineteenth century.* Since 1940. **XIII postal district was formed in 1851 by a nominal decree of the Senate on March 4, 1851 (COR-2, SP6, 1852, t. XXVI, Department 1st, number 2500).

Further reorganization of Tiflis post office is associated with the general changes made by the tsarist government in 1840 for civilian control of the Transcaucasian region. According to the nominative decree to the Senate on April 10, 1840, the provinces lying between the Black and Caspian seas were to form Georgian-Imereti province and the Caspian region. Tiflis was determined to be the main city of Georgia-Imereti, and Shamakhi of the Caspian region. This decree came into force since January 1841. It is mentioned in the first chapter of this book.

By that time, the post offices had been established:

the regional one in Tiflis;

the county ones of the first class – in Baku, Erivan, Nakhichevan, Kutaisi and Redoubt-Calais;

second class – in Gori, Dushet, Ananuri, Telavi, Sngnahe, Yelizavetpol, Cuba, Derbent and Vladikavkaz.

Yamskaya rush. Postage stamp.

County post offices were to report to the regional office of Tiflis. Further, with the abolition of earlier existing establishments in Georgia and the development of administrative management in the conquered areas of the region (which coincided with the intensification of military operations in the Black Sea and on the Caucasus line) – it is natural that the role and the importance of postal services in the South Caucasus should strengthen.

By the middle of forties there were operating the following types of postal service in Georgia and Tiflis:

1) Extra-mail, with which the correspondence was sent to the center on a regular basis, twice a week, according to a strictly determined route (St. Petersburg, Moscow, Novgorod, Tver, Tula, Voronezh provinces, the Land of the Don Cossack Host, Nizhny Novgorod, Odessa and Warsaw Provinces)

2) Heavy-mail – also to the center twice a week, with the division of correspondence to other places of the empire.

3) Easy-mail – to the postal places of the Caucasus and adjacent provinces.

4) Fly-mail – to border garrisons.

5) Relay mail – abroad, Vladikavkaz, according to a special work sheet with the payment of money for postal services.

There didn’t exist any telegraph lines at that time. The first telegraph line was opened in the Caucasus between Tiflis and Poti in 1860.

The formation of new province and region in the Transcaucasian region made Postal Department change the division of Russian into postal districts. In December 1840 taking into account the peculiarities of the region, it was decided to establish a new postal district for Georgian-Imereti province and for the Caspian region. [14] All post offices of Georgian-Imereti province and the Caspian region were transferred to the newly formed Mail District XII. Tiflis was identified to be the residence of the Postal inspector of a new district, and for his assistant – Shamakhi. The Cossacks were exempted from their obligation to accompany the mail in the Caucasus. They were replaced by postmen. The responsibilities of Tiflis post office had increased. With the addition of 10 postmen to accompany the mail its staff became 22 people. Tiflis regional post office in 1841 became known as provincial one. However, the order implemented in 1840 for civilian management of the Transcaucasian region, turned out to be in many ways uncomfortable.

In 1842, when inspecting the region, it was found out that due to its remoteness and the specific local conditions, the Ministry failed to establish there a proper supervision over the introduction of a new civil management. In addition, the intervention of the Ministries in the affairs of the Transcaucasian region often weakened the authority of the local manager. The Special Committee of the Caucasus established by the decree to the Senate of April 24, 1840, was only interested in the general direction of civil affairs in the region and failed to exercise proper supervision over the activities of new institutions in the Caucasus. According to the Minister of War Knyazh A.I.Chernyshev responsible for the general management of the affairs of the Transcaucasian region, to address the difficulties encountered, it was necessary to establish a special institution in St. Petersburg, which could keep all cases on civil management in Transcaucasia, having withdrawn them from Ministry, “until all the sections will get the complete control”, that was what he wrote to the Emperor Nicholas I on August 19, 1842. [15]

A temporary department was organized according to the Decree to the Senate on August 30, 1842. At the same time Caucasian Committee was also completely reorganized. In connection with this the reorganization of the main department of the Transcaucasian region located in Tbilisi also took place. On November 12, 1842, Tsar Nicholas I approved “Mandate to the General Directorate of the Transcaucasian region”, which determined the main goal: to rapidly establish “strong civil accomplishment” in the South Caucasus This “Mandate” raised the authorities of the Chief Commander of the region up to ministerial authority, acting in place. The Ministry could apply to the institutions reporting to them which were located in the South Caucasus only through the Chief Commander. Chief Directorate of the Council composition was limited to five members: three soldiers and two civilians. Military members of the Council in addition to their common duties were obliged to supervise departmental agencies which were out of local supervision: one was made responsible for training, the other supervised the customs and the third one took care of mail. In this regard, the positions of corresponding supervisors were abolished, including the position of postal Inspector of XII postal district.

The painter Adele Ommer de Gel. Cossack picket, 40-s of the XIX century.

The first member of the Main Directorate of the Transcaucasus region, who at the same time was managing mail department, was a lieutenant general and well-known Georgian poet Knyazh Alexander Chavchavadze, who came to this post on December 28, 1842. [16]

Thus, in 1840 the Transcaucasian region post offices were transferred from the direct control of the Postal Department of the Empire under the jurisdiction of the Chief Executive of the Transcaucasian region. The law of 1840 stated: “… the agencies, which are subject to special control, such as customs, educational and mail agencies, are under dependence and supervision of the Chief Executive of the Transcaucasian region which relating these agencies operates on the basis of regulations and rules, in particular for each of these existing agencies.” [17]

The final withdrawal of the twelfth postal district from under the control of Postal Department and all the functions to manage all the Agencies were transferred to the main authorities of the Transcaucasian region at the vicegerent graph M.S.Vorontsov.

In January 1845, when M. Vorontsov was appointed the vicegerent of the Caucasus, his authorities were determined by a special rescript of Nicholas I: “having laid on you, along with the title of Commander-in-chief of the troops in the Caucasus, the main command of the civil part in the region, as my vicegerent and consider it necessary, for the good of the service, to strengthen the authorities, which until now have been given to the chief superintendent of civil section, I, in my full confidence to you, command: all the cases, which according to currently existing order have to be submitted on behalf of the Chief Directorate of the Transcaucasia region to the Ministry to be solved, should be solved in place. Moreover, you are provided with an authority, when you find it necessary, to take all the measures required by the circumstances, in place, reporting to me directly all your actions, as well as the reasons these actions were caused by” [18] With this document the power of Knyazh Vorontsov was extended to the Caucasian region (later renamed in the Stavropol province by the decree to the Senate on May 2, 1847).

The vicegerent of the Caucasian region, Mikhail Vorontsov was a good administrator and a talented Russian official. He was born and brought up in England, where he received an excellent education. When he was the Head of the region postal roads were being laid and the bridges were being built. At the same time Tbilisi became a large administrative center, the city’s population increased, there appeared is a large number of beautiful new public and private buildings. All of this strongly demanded to improve postal service.

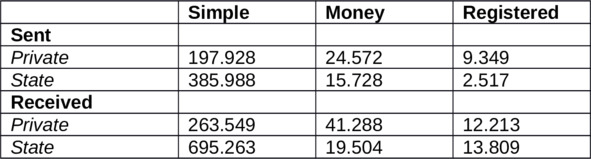

Table 2 illustrates the movement of mail only for the city of Tiflis in 1855. It shows the development of the cultural needs of the population of the Caucasian capital, which was primarily military and bureaucratic, in terms of coverage the city with postal services.

Table 2. The number of sent and received correspondence at the Tiflis province post office for 1855. [19]

Interesting statistics of the XIX century: in the late 50s for 100 inhabitants of the cities of the former Russian Empire there were 12,3 sent and received messages a year; for 100 inhabitants of the city of Tiflis there were 36 sent and received messages and in England for 100 inhabitants there were 300 messages. [20]

A cardinal measure, which contributed to the development of postal services, was the fact that postal stations of Tiflis province and the city of Tiflis had been withdrawn from the jurisdiction of the County Police and transferred as an experiment under the management of the postal authorities of the Caucasus for three years. This governmental action took place on October 26, 1857. [21]

The regional administration tried hard to facilitate the use of public postal services for the population. For example, there were declared opening and closure hours of post offices in the postal regulations of that time. But from “travelling persons, those who were not constantly living in the cities, such as neighboring landowners, farmers and roundabout residents” – letters were accepted at any inopportune time. [22]

I.I.Nazarov, appointed the member of Chief Management Board of the Trans-Caucasian Region and Manager of the postal department on January 1847, began to be called “Manager of postal department of the Caucasus and beyond the Caucasus.” In this position he replaced the Knyazh A.G.Chavchavadze. [23]

The painter Sir Robert Ker Porter. The interior of Russian post station, 1813.

However, the authority given the to the vicegerent M. Vorontsov by the Tsar, had been fully used by him only in 1848 in the process of reforms carried out in the post office of Tiflis province.

Since the 70s of the XVIII century in Russia there formed a system of postal services and transportation of the passengers by “mail”, which was almost unchanged until the middle of XIX century. Postal relays (stations), arranged at the expense of the state, were given to the individuals to be maintained. They had to have 25 horses, 10 wagons on wheels or sled at every station, as well as all the equipment necessary for postmen and mail transportation (horse harness, suitcases, bags, saddles, uniforms of postmen). A stationmaster was also responsible for hiring postmen. Even the serfs, released on the rent by the landlord, were allowed to be hired for this tedious service. The revenues of the postal station keeper consisted of the statutory fee (12 kopecks per 10 verst’s), proceeds from the sale of food and alcoholic beverages at the post office, from the placement of travelers for the night. Everything, which concerned the work of the post office, subjected to strict state regulation.

In winter and in summer the couriers were to be driven with a speed of 12 versts an hour, and in autumn and spring – 11 verst’s an hour. Other travelers were ordered to be driven more slowly: in winter and summer – 10 v/h, and in the spring and autumn – 8 verst’s an hour. Everyone who enjoyed the services of the post office, as well as all the correspondence was recorded in a special logbook.

In the reign of Emperor Nicholas I, vigorous measures had been taken to put in order earlier considerably neglected system of postal communications and postal stations. In 1837 he visited the Caucasus and signed a decree on the construction of mail houses every 3—4 postal stations on the Caucasian tracts. Along with the intensification of the movement of postal crews, the government of Nicholas I sought to establish a permanent staff of postal employees and station keepers. On these purposes the lease period of postal stations was increased from 3 to 12 years, and the rental amount was to be determined not at the auction, but according to official estimates fixed for each post office. In Nicolas’s list of activities to improve the situation in the Russian Empire there was the item of constructing on the main road’s postal stations uniform in appearance and convenient for travelers.

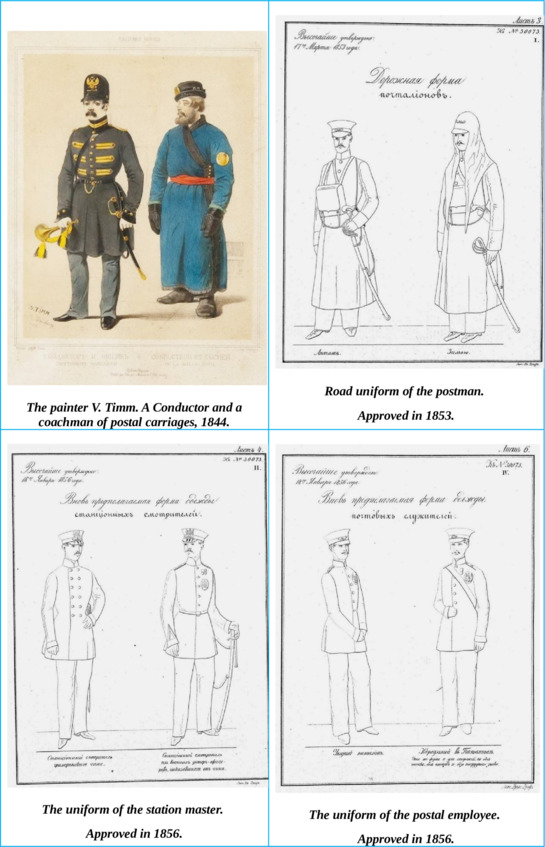

A new sample of postal uniform for the postmen was introduced in the 40s: red cloth caftan with a white belt. It is worn over the ordinary dress. Peaked caps were also red. A postman wore on his chest a brass badge with the state national emblem and a strap with the horn over the shoulder. Special uniforms existed for mail conductors and coachmen. Later, in the years 1856—1857 the mail uniform was changed.

An interesting analysis of the postal service was done by B.A.Kaminsky, who described a postal rush in the Caucasus. He gives a more complete understanding of the need to reform the postal service, and a haste to issue a stamp of Tiflis city post office. [24]

In 1831, for the first time several postal stations were sold under the responsibility of the individuals – postal landlords. At the same time the question was raised about the management of the postal rush in the region on the same basis as in the internal provinces of Russia, and also it was mentioned that the supervision over the stations, which before was the responsibility of the heads of military guards, should be transferred to the Post Authority. At the end of 1833 there were already 90 postal stations in the region. But at these stations there were no station houses yet, and postal landlords were placed together with the Cossack posts in the huts or even in mud huts.

The uniform of the postman of 19th century.

The uniform of the postman of 19th century.

Georgia started to construct the station houses in the years 1834—1835. These houses were considered to be connected to military posts. By the nominal decree of 13 July 1830 to the sum of 80,000 rubles in silver, assigned to build these houses, a new sum of 50,000 was added.