The Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire. 1796 to 1816

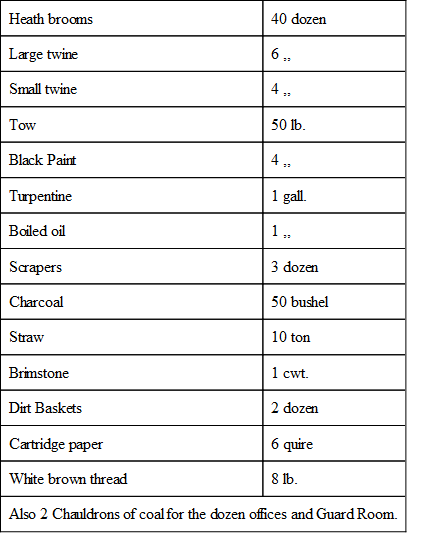

This letter went on to authorise the agent to procure tin mess-cans, wooden bowls, platters, and spoons for 3,000 prisoners at Wisbeck [sic] and Lynn, and to inform him that 1,000 hammocks, 1,000 palliasses, 1,000 bolster-cases, also 5,000 sets of bedding, were on their way from London, and that the prisoners from Falmouth would bring their own hammocks with them. 24 At the end of the letter is a note as to stores as follows:

These stores, it must be borne in mind, were only for the use of the occupants of that portion of the prison which was complete, about one fourth of the whole.

Mr. Delafons does not appear to have taken up the duties assigned to him, for on the 26th March, only eight days after the date of the letter appointing him agent, he sent in his formal resignation. Mr. Dent, the storekeeper, in conjunction with Captain Woodriff, the transport officer, acted till the appointment of James Perrot on 7th April 1797, at a salary of £400 a year and £30 for house rent, until quarters could be built for him in the prison. This amount was double that of any other agent, but it must be remembered that Mr. Perrot was not a naval officer in receipt of full pay. There was a difficulty in finding lodgings in the vicinity, and the clerks were allowed 1s. a day extra till accommodation could be found for them also at the prison.

To assist the agent, Mr. Challoner Dent was appointed storekeeper from 1st April 1797 on getting two gentlemen as security for £1,000. There were clerks and ten turnkeys, twelve labourers at 12s. a week, and a lamplighter at 13s. a week. The chief clerk and Dutch interpreter was Mr. James Richards.

The transport officer in charge, Captain Woodriff, had to make arrangements for the conveyance of the expected prisoners to Norman Cross, and for the victualling. As to the former, he was on the 23rd March directed without loss of time to proceed to Norman Cross near Stilton, and thence to Lynn to report as to the best anchorage there, and the best mode of transporting the prisoners of war expected. He was to consult a Mr. Hadley, who proposed 1s. a head for removing the prisoners, which was considered exorbitant and quite out of the question.

On 29th March, however, he was directed to enter into an agreement with Mr. Kempt, to convey the prisoners from Lynn to Yaxley at 1s. 6d. per head, and Kempt’s partner was to victual them on the following daily ration: 1 lb. of bread or biscuit, ¾ lb. of good fresh or salt beef.

The time occupied by the barges in which the men were to be conveyed would probably be about three days, and the dietary could not be much varied. At the date when this contract was made, nearly fifty years before the first railway in this district was opened, the waterways offered the easiest and cheapest channel for the transport of heavy goods across the great Fen district. The rivers, natural and artificial, and the navigable drains and cuts, fulfilled a double purpose, and were maintained by taxes and tolls not only for the drainage of the Fens, but as waterways for the lucrative traffic which was constant along their surface.

It was by water that George Borrow and his mother travelled to join his father in his quarters at Norman Cross, and we have again a graphic account of the impressions left on the child’s mind by the journey from Lynn to Peterborough when the washes and Fenlands were flooded—an account written long after the child had come to man’s estate, when distance had lent enchantment to the view and certainly depth to the pools on the towing paths.

“At length my father was recalled to his regiment, which at that time was stationed at a place called Norman Cross, in Lincolnshire, or rather Huntingdonshire, at some distance from the old town of Peterborough. For this place he departed, leaving my mother and myself to follow in a few days. Our journey was a singular one. On the second day we reached a marshy and fenny country, which owing to immense quantities of rain which had lately fallen, was completely submerged. At a large town we got on board a kind of passage-boat, crowded with people; it had neither sails nor oars, and these were not the days of steam-vessels; it was a treck-schuyt, and was drawn by horses.

“Young as I was, there was much connected with this journey which highly surprised me, and which brought to my remembrance particular scenes described in the book which I now generally carried in my bosom. The country was, as I have already said, submerged—entirely drowned—no land was visible; the trees were growing bolt upright in the flood, whilst farmhouses and cottages were standing insulated; the horses which drew us were up to the knees in water, and, on coming to blind pools and ‘greedy depths,’ were not unfrequently swimming, in which case the boys or urchins who mounted them sometimes stood, sometimes knelt, upon the saddle and pillions. No accident, however, occurred either to the quadrupeds or bipeds, who appeared respectively to be quite au fait in their business, and extricated themselves with the greatest ease from places in which Pharaoh and all his host would have gone to the bottom. Nightfall brought us to Peterborough, and from thence we were not slow in reaching the place of our destination.” 25

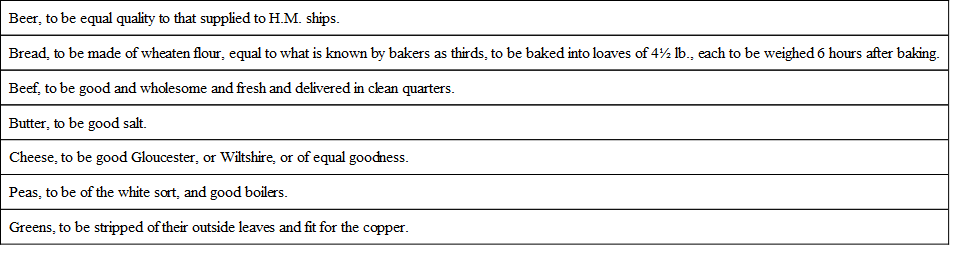

A Mr. James Hay of Liverpool was the first contractor for victualling the prisoners at Norman Cross, the specification for the quality of the food supplied being as follows:

The reader must bear these conditions in mind if he would be in a position to discount George Borrow’s description (in the passage quoted a few pages back) of the food supplied to those prisoners whom he remembered with such sympathy in his later life; and he must, in forming his judgment of the treatment accorded to the prisoners, remember that, as evidence, the stern facts of a contract, with penalties of fine and imprisonment for its breach, are of more value than the recollections of a child, given in the rhetorical language of a romantic enthusiast.

The victualling under the terms of the contract commenced on the 12th April 1797. The contractor was called upon to supply per head daily, 1 lb. of beef, 1 lb. of biscuit, 2 quarts of beer, and to find casks and water at 11d. per day, being the same terms as those on which the goods were supplied at Plymouth and Falmouth. Mr. Hay wrote that no butcher within fifty miles of Norman Cross would supply cow, heifer, or ox beef for less than 44s. per cwt., but he offered to supply it at 43s., and this was agreed to. 26

No tables or benches were to be provided. Hammocks were supplied, but no clews nor lanyards (the cords to suspend them by); these the prisoners had to make for themselves, jute being supplied to them for that purpose, one ton to every 400 men.

The new agent, Mr. Perrot, who came from the prison at Porchester Castle, appears to have applied for other comforts, as we infer from the following communication addressed to him from the Transport Office:

“We cannot allow any razors or strops for the use of the prisoners at Norman Cross. We see no reason for your appointing barbers, to shave the prisoners, the razors sent to Porchester having been intended more for shaving the Negro prisoners from the West Indies.”

Does the fact that the names of the two first agents appointed, Delafons and Perrot, were French, and that they were not naval officers as at other prisons, justify the supposition that our Government in their anxiety to study the interests of the prisoners and to satisfy the French, were trying the experiment of appointing a British subject of French birth or of French origin as agent to this Depot? Such a supposition might account for the fact of Mr. Delafons’ resignation a few days after his appointment. A man in sympathy with the French might well find, on entering into the particulars of his duties, that he could not conform to the regulations regarded by the Government as necessary for the discipline of prisons—regulations, for breaking which, many prisoners lost their lives. Does not this letter to Mr. Perrot also read as though he were making a frivolous application to the Government?

Whatever the worth of this supposition may be, we find that on the 2nd January 1799, less than two years after his appointment, Mr. Perrot’s name disappears from the books, and that Captain Woodriff, R.N., the transport officer who had been acting for the transport office in the district, was asked to take over the duties of the agent, receiving a small addition to his previous salary.

The duties of the Depot agent and the district agent must have previously overlapped, for it was Captain Woodriff, the Transport officer, who two years before was making all the arrangements for the reception and maintenance of the prisoners, and who shortly after their arrival, having employed some of them to spread the gravel in the exercise yards, paying them 3d. a day for doing it, was called upon by the Government to furnish the information as to the wages and the prices of provisions in the neighbourhood, given in the extract from his report printed in the footnote on p. 16.

Captain Woodriff held the post of agent at Norman Cross from his appointment in 1799 to the Peace of Amiens in 1802, having previously from 2nd September 1796, when he was appointed agent of the Transport Office at Southampton, been engaged in duties associated with the care of prisoners of war. In July 1808 he was appointed agent for prisoners of war at Forton, holding office until 1813. He thus spent, in all, eleven years of his long services as a naval officer, assisting the Transport Board in their important work as the custodian of the prisoners. In the Appendix will he found a short biography of Captain Woodriff, collated by Mr. Rhodes. It gives an insight into the adventurous and uncertain career which, during the epoch with which this history has to do, might be that of a naval officer of distinction, and shows that the custodian of the prisoners at Norman Cross and Forton was himself at one time an English prisoner at Verdun. 27

On the 24th March the troops who were to form the garrison had marched into their quarters, this event being noted in his diary by John Lamb, a farmer and miller living at Whittlesey, about seven miles from Norman Cross—“24th March 1797 the soldiers came to guard the Barracks. The Volunteers did not much like it; they liked drinking better.” All arrangements being sufficiently advanced, the prisoners sent from Falmouth, who for several days had been waiting, cooped up in the Transports at Lynn, were disembarked and put into lighters, to be brought by water to Yaxley and Peterborough, and the first prisoners passed through the prison gates on 7th April 1797, just four months from the commencement of the building.

CHAPTER III

ARRIVAL AND REGISTRATION OF THE PRISONERS

A prison is a house of care, A place where none can thrive;A touchstone true to try a friend, A grave for one alive;Sometimes a place of right, Sometimes a place of wrong,Sometimes a place of rogues and thieves, And honest men among.Inscription in Edinburgh Tolbooth.We have now arrived at that stage in the story of the Norman Cross Depot when, although the whole of the buildings were not yet erected, sufficient progress had been made for the occupation of a part of them. Two quadrangles were ready, each of them containing caserns and the necessary accessory buildings for the care and safe custody of 2,000 men. The other two quadrangles were rapidly approaching completion, one for 2,000 prisoners, the other, the north-eastern block, for a smaller number, as it was in part devoted to the accommodation of the sick, who slept in bedsteads instead of in hammocks, and therefore occupied a far greater space than the healthy men.

In this north-eastern square each casern was artificially warmed by fires, and in every extant plan these blocks are shown to have chimneys, while all the others have merely ventilators. The buildings were cut up by partition walls into wards, and surgeons’ and attendants’ rooms, which further interfered with their capacity; but, notwithstanding the limited number of the occupants of this quadrangle, it is probable that in the most crowded period of its occupation the prison held, including the sick, and the occupants of the boys’ prison outside the boundary wall, at least 7,000 prisoners.

On the 10th April 1810 a return made of all the prisoners of war in England on that day shows 6,272 at Norman Cross. These returns are few and far between, and may well have missed a period of overcrowding; the lowest of any of them, one rendered in 1799, gives the number as 3,278.

To appreciate the details of the life of the prisoners, the reader must grasp the magnitude of the experiment which was being initiated at this Depot, where a number of men, equal to the adult male population of a town of 30,000 inhabitants, were to be confined within four walls, with no society but that of their fellow prisoners, no female element, no intercourse with the outside world, except that in the prison market, in which they were served by foreigners, whose language they did not understand. In this community order and discipline had to be maintained, while at the same time ordinary humanity demanded that these unfortunate men, who had committed no crime, who were in a foreign prison for doing their duty and fighting their country’s enemies, must be treated with all possible leniency.

The exigencies of the war, and the circumstances under which many of the men arrived at the prison, were not conducive to peace and order, and the posts of agent of the Depot and of transport officer carried great responsibility. This we can realise from an occurrence, a vivid example of the horrors of war, concerning which Captain Woodriff had to hold an inquiry as one of his first duties in connection with the Depot. Among the thousand prisoners who, when the prison was opened, were already on their way to Norman Cross from Portsmouth, Falmouth, Kinsale, and Chatham, were men who had been conveyed on board the Marquis of Carmarthen transport, on which ship there had been a mutiny of the prisoners. In the fray seven men were killed and thirty-seven dangerously wounded, but the mutiny was quelled and all the prisoners accounted for, except one, who was the murderer of one of the crew. Next day he was discovered and placed in irons, with a sentry over him. He asked to be shot, and in the absence of the captain of the vessel, who protested against his wish being acceded to, the officer commanding the troops, one Lieutenant Peter Ennis of the Caithness Militia, shot the unfortunate man, and had the body thrown overboard. This happened three days after the mutiny. The matter was investigated and reported upon by Captain Woodriff at Norman Cross. The prisoners gave evidence that they had mutinied on account of the badness of the water and provisions, and complained that Inglis, or Ennis, was brutal to them. 28 The same causes were assigned for another mutiny on the British Queen transport, which had to be reported upon by the agent at Norman Cross. To quell this outbreak, the mutineers were fired on by the captain’s orders, twelve being wounded, but none killed.

The earliest arrivals on the 7th April 1797 were the sailors from the frigate Réunion and 172 from the Révolutionnaire man-of-war, which had been brought in by The Saucy Arethusa. These were brought by water to Yaxley. The next batch arrived on the 10th, and were landed from the barges at Peterborough, proceeding to Norman Cross guarded by troopers.

The latter detachment was landed, according to Mr. Lamb’s diary, at Mr. Squire’s close on the south bank of the river at Peterborough. This Mr. Squire was later appointed the agent to look after the prisoners on parole in Peterborough and its neighbourhood.

Other prisoners followed in rapid succession, their names, with certain particulars, being entered in the French and the Dutch registers, which were kept at the prison. The French registers number six large volumes, ruled in close vertical columns, which extend across the two open pages. The first column, commencing at the left-hand margin, is for the numbers (the current number), which run consecutively to the end of the series; the second is headed, “Where and how taken”; the third, “When taken”; fourth, “Name of vessel”; fifth, “Description of vessel,” such as Man-of-War, Privateer, Fishing Vessel, Greenlander; sixth, “Name of prisoner”; seventh, “Rank”; eighth, “Date of reception at the prison”; ninth, a column of letters which signify D, “discharged,” E, “escaped,” etc., and the date of discharge. The Dutch register is in five volumes only, but the entries are fuller than those in the French register, there being thirteen columns across the two pages. The first, the “Current number”; second, “Number in general entry book”; third, “Quality” (sailor, drummer, gunner, mate, etc.); fifth, “Ship”; sixth, “Age”; seventh, “Height” (range from 4 ft. 11½ in. to 5 ft. 10½ in.); eighth, “Hair” (all brown); ninth, “Eyes” (the majority blue, some brown and a few grey); tenth, “Visage” (as round and dark, oval and ruddy); eleventh, “Person” (middle size, rather stout); twelfth, “Marks or wounds” (e.g. None—Pitted with small-pox—Has a continual motion with his eyes); thirteenth, “When and how discharged” (Dead; Exchanged; etc.). 29

In both registers there are occasional marginal notes. A few examples of the value of these registers as sources of information will suffice for this history. Commencing with the French, we find that 190 French soldiers, captured on 7th January 1797 in La Ville de L’Orient, were received into custody 26th April 1797. Of these, the first one recorded as dead was a soldier Jacques Glangetoy, on the 9th February 1798. Of ninety-four captured on 31st December 1796 on La Tartuffe frigate, many are only entered by their Christian names, as Félix, Hilaire, Eloy, Guillaume, etc. On 11th October 1799 there came a batch from Edinburgh, captured 12th October 1798 in La Coquille frigate, off the Irish Coast. On the 28th July 1800 the garrison of Pondicherry, captured 23rd August 1793, were, after seven years of captivity at Chatham, transferred to Norman Cross. On the 6th October of the same year, 1,800 prisoners captured at Goree, and other places in the West Indies, were transferred from Porchester.

From the Dutch register we gather that it was the Dutch prisoners who filled the prison to overflowing a few months after it was opened. The great naval battle already alluded to as imminent when the prison was building, took place on 11th October 1797, off Camperdown, when Admiral Duncan, after a severe engagement, defeated the Dutch fleet under Admiral de Winter, capturing the Cerberus, 68 guns; Jupiter, 74; Harleem, 68; Wassenaar, 61; Gelgkheld, 68; Vryheid, 74; Delft, 56; Alkmaar, 56; and Munnikemdam, 44. The Dutch fought gallantly, and the ships they surrendered were well battered.

The loss of life was appalling, and the number of Dutch prisoners brought in by the English Admiral was 4,954, the majority of these being ultimately sent to Norman Cross, where they began to arrive in November 1797. The first entry of prisoners taken in this great battle is a list of 261 from Admiral Ijirke’s ship Admiral de Vries.

Subsequent arrivals were crews of privateers and merchant ships, fishermen, and soldiers. Entries in later years show that among the prisoners sent to Norman Cross were many other civilians besides the fishermen; these were not retained in the prison, but were allowed out on parole or were released. Many fishing vessels were captured, the crew averaging six; these sailors were sent to Norman Cross, and after a few days’ confinement were “released” by the Board’s order. The soldiers were entered in a separate register. The first batch were taken from the Furie, captured by the Sirius on the 14th October 1798, they were received at Norman Cross on the 20th November of the same year, and are described in the appropriate column as bombardiers, cannoniers, passengers, etc. To ascertain what was the ultimate destination of the prisoners, Mr. Rhodes has made an analysis of the information given in the registers for the individual members of the crew of selected ships. As to the first ship to which he applied this method, he found that of the crew, the quartermaster was exchanged, 7th April 1798, one of the coopers was allowed to join the British Herring Fishery, the majority of the officers were allowed on parole at Peterborough, several seamen joined the British Navy, one was discharged on the condition he elected to serve under the Prince of Orange, one enlisted in the York Hussars, and at various dates many enlisted in the 60th Regiment of Foot. Of the soldiers, the officers were allowed on parole at Peterborough, some privates joined the Royal Marines at Chatham, nine joined the 60th Foot, and in 1800 the remainder, with the sailors, were sent to Holland under the Alkmaar Cartel. 30 An analysis of the columns giving the disposal of the next ship’s company shows that nine were on parole at Peterborough, two were sent to serve under the Prince of Orange, two joined the British Herring Fishery, seven the British Navy, two the Merchant Service, four the Dutch Artillery, three died, ninety-three enlisted in the 60th Foot, and the rest were sent to Holland.

In explanation of the preponderance of recruits for the 60th Foot, it may be pointed out that this regiment was originally raised in America in 1755, under the title of the 62nd Loyal American Provincials, and consisted principally of German and Swiss Protestants who had settled in America, the principal qualification being that they were “antagonistic to the French.”

In 1757 the title was changed to the 60th Royal Americans, which title it bore till 1816. The regiment is now the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. It served in America and the West Indies up to 1796. It was in England till 1808, when it went to the Peninsula. At Quebec it was described by General Wolfe as “Celer et Audax,” which is now the regimental motto.

The crew of the Jupiter, with the captain, four lieutenants, and the Admiral’s steward, 144 in all, were received 8th November 1797, and were ultimately distributed in much the same manner, fifty entering the 60th. In December, a month after their reception, the Dutch captain and two lieutenants of this ship were sent to London to give evidence against two British subjects who were taken in arms against this country on board the Jupiter when it was captured. Coach hire was allowed them, and double the subsistence usually given to officers on parole.

Of the crew of the privateer Stuyver, numbering thirty-eight, captured on 1st June 1797 by the Astrea, eight joined the English Navy.

From the registers we get information as to the length of time the various crews, etc., remained in captivity. Thus the crew of the Furie, a Dutch frigate, numbering 115, received at Norman Cross on the 4th October 1798, remained there until the Peace of Amiens in February 1802; the officers were out on parole, and the majority of them were released in February 1800, under the Alkmaar Cartel.

Unfortunately the registers are very imperfectly kept; they are filled in without any regularity; the entries appear to have been copied from other documents, and there are weeks and months when column after column is left blank. There is no doubt that the staff was too limited for the work that was expected of it. Incomplete and bad clerical work was the result. The names of several sloops and schooners are duly returned as “Taken,” but in the columns “By whom and when taken,” is the entry “Unknown.” There is an entry of three names bracketed together, probably the crew of a fishing-boat: “Andreas Anderson, 1st Steerman; Johanna Maria Dorata Anderson, Woman, his wife; Margrita Dorothea Anderson, child. Received into custody 31st May 1800.” On 3rd June they are marked as “On parole at Peterborough.”