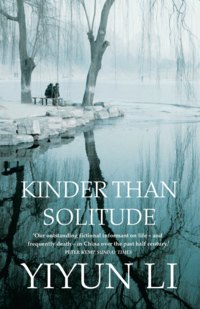

Kinder Than Solitude

The bedroom Ruyu was to share with Shaoai was the biggest in the house and used to belong to Uncle and Aunt. Aunt apologized for not having had time to make many changes, besides installing a new student’s desk in the corner of the room. The other bedroom—Shaoai’s old bedroom—was not large enough to accommodate the desk, so it wouldn’t do, Aunt explained, since Ruyu needed her own quiet corner to study. Ruyu mumbled something halfway between an apology and an acknowledgment, though Aunt, flicking dust off the shade of the desk lamp—new also, bought on sale with the desk, she said—did not seem to hear. Ruyu wondered if her grandaunts had considered how their plan for her would change other people’s lives; if they had known anything, they had not told her, and it perplexed her that a small person like herself could cause so much inconvenience. At dinnertime, Shaoai had scoffed when Aunt reminded her to show Ruyu how to clip the mosquito netting, saying that even a child could do that, to which Aunt had replied in an appeasing tone that she just wanted to make sure Ruyu felt informed about her new home. Uncle, reticent, with a sad smile on his face, had come to the dinner table in a threadbare undershirt, but had hurried back to the bedroom when Aunt had frowned at him, and returned in a neatly buttoned shirt. From the expectant looks on Aunt’s and Uncle’s faces, Ruyu knew that the dinner had been prepared for her with extra effort, and, later in the evening, when she fetched water from the wooden bucket next to the kitchen for her washstand, she overheard Uncle comforting Aunt, telling her that perhaps the girl was simply tired from her journey, and Aunt replying that she hoped Ruyu’s appetite would return, as it’s certainly not healthy for a person her age to eat only morsels like a chickadee.

Someone walked close to the bedroom, a shadow looming on the curtain. Ruyu closed her eyes when she recognized Shaoai’s profile. Aunt whispered something to which Shaoai did not reply before entering the bedroom. She stopped in the semidarkness and then turned on the light, a bare bulb hanging low from the ceiling. Ruyu closed her eyes tighter and listened to Shaoai fumble around. After a moment, an electric fan turned on, its droning the only sound in the quietness of the night. The breeze instantly lifted the mosquito netting, and with an exaggerated sigh Shaoai tucked the bottom of the netting underneath the mattress. “You have to be at least a little smarter than the mosquitoes,” she said.

Ruyu did not know if she should apologize and then decided not to open her eyes.

“You shouldn’t wrap yourself up in the blanket,” Shaoai said. “It’s hot.”

After a pause, Ruyu replied that she was all right, and Shaoai did not pursue the topic. She turned off the light and changed in the darkness. When she climbed into the bed from her side and readjusted the mosquito netting, Ruyu regretted that she had not prepared herself by turning away so that her back faced the center of the bed. It was too late now, so she tried to hold her body still and breathe quietly. Please, she said, sensing that she was on Shaoai’s mind, please mask me with your love so they can’t feel my existence.

Later, when Shaoai was asleep, Ruyu opened her eyes and looked at the mosquito netting above her, gray and formless, and listened to the fan swirling. She had been off the train for a few hours now, but still her body could feel the motion, as though it had retained—and continued living—the memory of traveling. There was much to get used to in her new life, a public outhouse at the end of the alleyway Moran had shown her earlier; an outdoor spigot in the middle of the courtyard, where Ruyu had seen Boyang and a few other young men from the quadrangle gather after sunset, topless, splashing cold water onto their upper bodies and taking turns putting their heads under the tap to cool down; a bed shared with a stranger; meals supervised by anxious Aunt. For the first time that day, Ruyu felt homesick for her bed tucked behind an old muslin screen in the foyer of her grandaunts’ one-room apartment.

3

Celia’s message on Ruyu’s voice mail sounded panicked, as though Celia had been caught in a tornado, but Ruyu found little surprise in the emergency. That evening it was Celia’s turn to host ladies’ night. These monthly get-togethers had started as a book club, but, as more books went unfinished and undiscussed, other activities had been introduced—wine tasting, tea tasting, a question-and-answer session with the president of a local real estate agency when the market turned downward, a holiday workshop on homemade soaps and candles. Celia, one of the three founders of the book club, had nicknamed it Buckingham Ladies’ Society, though she used the name only with Ruyu, thinking it might offend people who did not belong to the club, as well as some who did. Not everyone in the book club lived on Buckingham Road. A few of them lived on streets with less prominent names: Kent Road, Bristol Lane, Charing Cross Lane, and Norfolk Way. Properties on those streets were of course more than decent, and children from those houses went to the same school as hers did, but Celia, living on Buckingham, could not help but take pleasure in the subtle difference between her street and the others.

Ruyu wondered if the florist had misinterpreted the color theme Celia had requested, or if the caterer—a new one she was trying out, upon a friend’s recommendation—had failed to meet her expectations. In either case, Ruyu’s presence was urgently needed—could she please come early, Celia had said in the voice mail, pretty please?—not, of course, to right any wrong but to bear witness to Celia’s personal tornado. Being let down was Celia’s fate; life never failed to bestow upon her pain and disappointment she had to suffer on everyone’s behalf, so that the world could go on being a good place, free from real calamities. Celia’s martyrdom, in most people’s—less than kind—opinion, amounted to nothing but a dramatic self-centeredness, but Ruyu, one of the very few who took Celia’s sacrifice seriously, understood the source of her suffering: Celia, though lapsed, had been brought up by Catholic parents.

Edwin and the boys were off to dinner and then to a Warriors game, Celia told Ruyu when she arrived at the Moorlands’. A robin had flown into a window that morning, knocking itself out and setting off the alarm, Celia said, and thank goodness the window was not broken and Luis—the gardener—was here to take care of the poor bird. The caterer was seventeen minutes late, so wasn’t it wise of her to have changed the delivery time to half an hour earlier? In the middle of recounting an exchange between the deliveryman and herself, Celia stopped abruptly. “Ruby,” she said. “Ruby.”

“Yes,” Ruyu said. “I’m listening.”

Celia came and sat down with Ruyu in the breakfast nook. The table and the benches were made of wood reclaimed from an old Kensington barn where Celia’s grandmother, she liked to tell her visitors, used to go for riding lessons. “You look distracted,” Celia said, pushing a glass of water toward Ruyu.

The woman Celia thought of as Ruby should have unwavering attention as an audience. Ruyu thanked Celia for the water and said that nothing was really distracting her. To Celia’s circle of friends—many of whom would arrive soon—Ruyu was, depending on what was needed, a woman of many possibilities: a Mandarin tutor, a reliable house- and pet-sitter, a last-minute babysitter, a part-time cashier at a confection boutique, an occasional party helper. But her loyalty, first and foremost, belonged to Celia, for it was she who had found Ruyu these many opportunities, including the position at La Dolce Vita, a third-generation family business owned by a high school friend of Celia’s.

Celia did not often notice anything beyond her immediate preoccupation, but sometimes, distraught, she was able to perceive other people’s moods. In those moments she adamantly required an explanation, as though her tenacious urge to know someone else’s suffering offered a way out of her own. Ruyu wondered whether she looked disturbed and wished she had touched up her face before entering the house.

“You are not yourself today,” Celia said. “Don’t tell me you had a tough day. The day is already bad enough for me.”

“Here’s what I have done today: I was in the shop in the morning; I stopped at the dry cleaners; I fed Karen’s cats; I took a walk,” Ruyu said. “Now, tell me how hard my day could be.”

Celia sighed and said that of course Ruyu was right. “You don’t know how I envy you.”

Ruyu had been told this often, and once in a while she almost believed Celia to be sincere. “You sounded dreadful in your voice mail,” Ruyu said. “What happened?”

What happened, Celia said, was pure outrage. She went away and came back with a pair of white T-shirts. Earlier that afternoon she had attended a meeting for the fundraising of a major art festival in San Francisco, and on the committee was a writer whose teen detective mysteries were recent bestsellers. “You’d think it’s not too much to ask a writer to sign a couple of shirts for his fans,” Celia said. “You’d think any decent man would have more respect than this.” She dropped the T-shirts on Ruyu’s lap in disgust, and Ruyu spread them on the table. In black permanent marker and block letters, the writer had written, “To Jake, a future orphan” and “To Lucas, a future orphan,” followed by his unrecognizable signature.

Perhaps the writer had only meant it as a joke, a sabotaging wink to the boys behind their mother’s back; or else it’d been more than a joke, and he’d felt called to reveal an absolute truth that a child did not learn from his parents. “Unacceptable,” Ruyu said, and folded up the shirts.

“Now, what do I do with them? I promised the boys I would get them his signature. How do I explain to them that this person they admire is a jerk? An asshole, really,” Celia said, and gulped down some wine as if to rinse away the bad taste. “Thank goodness Edwin picked them up from school so I didn’t have to deal with this until later.”

Poor gullible Celia, believing, like most people, in a moment called later. Safely removed, later promises possibilities: changes, solutions, rewards, happiness, all too distant to be real, yet real enough to offer relief from the claustrophobic cocoon of now. If only Celia had the strength to be both kind enough and harsh enough with herself to stop talking about later, that heartless annihilator of now. “Exactly what,” Ruyu said, “will you say to them later?”

“That I forgot?” Celia said uncertainly. “What else can I say? Better for your children to be annoyed with you, better for your husband to be disappointed by you, than break anyone’s heart. I’ll tell you, Ruby, it’s smart of you not to have children. Smarter of you to not want another husband. Stay where you are. Sometimes I think about how simple and beautiful your life is—and that, I say to myself, is how a woman should treat herself.”

Had Celia been a different person, Ruyu might have found her words distasteful, malicious even, but Celia, being Celia, and never doubting the truth of her own words, was as close to a friend as Ruyu would admit into her life. She unfolded the shirts and studied the handwriting, and asked Celia if she had another pair of white T-shirts. Why? Celia asked, and Ruyu said that they might as well fix the problem themselves. You don’t mean it, Celia said, and Ruyu replied that indeed she did. What’s wrong with borrowing the writer’s name and making two boys happy?

Celia hesitantly offered another set of T-shirts, and Ruyu asked Celia what message she wanted her children to wear to school.

“Are you sure this is the right thing to do? I don’t want my children to think I lie to them.”

The writer, Ruyu wanted to remind Celia, had not lied. “I’m the one lying here,” she said. “Look away.”

“What if the other kids at school realize that the signatures are fake? Is it even legal to do this?”

“There are worse crimes,” Ruyu said. Before Celia could protest, Ruyu wrote, in her best approximation of the writer’s handwriting, a message of hope and affection to the beloved Jake and Lucas. After signing and dating the shirts, Ruyu folded them and said she would get rid of the original evidence to spare Celia any wrongdoing.

A car engine was heard outside the house; another car door opened and then closed. Celia’s guests were arriving, and she assumed the nervous, high-pitched energy of onstage-ness. Ruyu waved for Celia to go and greet her guests. She stuffed the two unwanted T-shirts in her bag, went into the boys’ bedrooms, and placed the ones she’d signed on their pillows.

The evening’s topic was a recent bestseller written by a woman who called herself a “Chinese tiger mom.” As always the gathering started with the exchange about children and husbands and family vacations and coming holiday recitals and performances. Ruyu drifted in and out of the living room, refilling wineglasses and passing out food, her position somewhere between a family friend and a hired hand. Affable with the guests, many of whom used her service in one way or another, Ruyu nevertheless stayed out of conversations, contributing only an encouraging smile or a courteous exclamation. Knowing how the women saw her, Ruyu did not find it difficult to play that role: an educated immigrant with no advanced job skills; a single woman no longer young; a renter; a hire trustworthy enough, good and firm with dogs and children alike and never flirtatious with husbands; a woman lucky to have been taken under Celia’s wing; a bore.

When the book discussion began, Ruyu withdrew to the kitchen. At most gatherings she would not have absented herself so completely, as she did enjoy sitting on the periphery. She liked to listen to the women’s voices without following what they said, and look at their soft-hued scarves, their necklaces designed by a local artist they patronized as a group, and their shoes, elegant or bold or unself-consciously ugly. To be where she was, to be what she was, suited her. One would have to take oneself much more seriously to be someone definite—to pose as a complete outsider; or to claim the right to be a friend, a lover, a person of consequence. Intimacy and alienation both required an effort beyond Ruyu’s willingness.

Celia stopped at the entrance to the kitchen. “Don’t you want to sit with us?” she asked. Ruyu shook her head, and Celia waved before walking away to the bathroom. If Celia pressed her again, Ruyu would say that the topics of parenting, school options for children, and the tiger mom—who was not even Chinese but called herself Chinese for sensational reasons—held little interest for her.

Ruyu studied the flowers on the table, an assortment of daisies and irises and fall leaves arranged in a half pumpkin, around which a few persimmons had been artfully placed. She moved one persimmon farther away and wondered if anyone would notice the interfered-with composition, less balanced now. Celia’s life, busy and fluid with all sorts of commitments and crises, was nevertheless an exhibition of mindfully designed flawlessness: the high, arched windows of her home overlooked the bay, inviting into the living room an ever-changing light—golden Californian sunshine in the summer afternoons, gray rain light in the winter, morning and evening fog all year round; the three silver birch trees in front of the house—birch, Celia had told Ruyu, must be planted in clusters of three, though why she did not know—complemented the facade with their white bark, adding asymmetry to the otherwise tedious front lawn; the shining modernness of the kitchen was softened by a perfect display of still lifes—fruits, flowers, earthen jars, candles in holders, their colors in harmony with seasons and holidays; and the many corners in the house, each its own stage, showcased a lonely cast of things inherited or collected on this or that trip. Celia’s family, always on the run—soccer practice, music lessons, pottery classes, yoga, fundraising parties, school auctions, trips to ski, to hike, to swim in the ocean, to immerse in foreign cultures and cuisines—had done a good job of leaving the house undisturbed, and Ruyu, perhaps more than anyone else, enjoyed the house as one would appreciate a beautiful object: one finds random pleasure in it, yet one does not experience any desire to possess it, or any pain when it passes out of one’s life.

From the living room, the women’s voices meandered from indignation to doubt to worry to panic. Over the past few years Ruyu had got to know each of the women, through these gatherings and working for some of them, well enough to pity them when they had to come into a group. None of them was uninteresting, but together they seemed to negate one another’s individual existence by their predictability. Never did anyone show up disheveled, never did any one of them dare to admit to the others that she was lonely, or sad, or suffocated under the perfect facade of a good life. It must be the isolation that sent them to seek out others like them, but in Celia’s living room, sitting together, the women seemed only more bravely isolated.

Ruyu had first met Celia seven years ago, when Celia had been looking for a replacement for their live-in nanny, who was returning to Guatemala with enough money to build two houses—one for her parents, and one for herself and her daughter. Of course it crushed her heart that Ana Luisa had to leave, Celia had said when she called Ruyu, who had replied to Celia’s ad on a local parenting website; but wouldn’t anyone feel happy for her? Ruyu had been an oddity among the more ordinary applicants—she had no previous child-care experience, and she lived rather out of the way. But having a Mandarin-speaking nanny would be an advantage over having one who spoke Spanish, Celia had explained to Edwin before she called Ruyu.

She did not have a car, Ruyu had said when Celia invited Ruyu to the house for an interview, and there was no public transportation where she lived, so could Celia, if interested, drive down to interview her? Later, when Ruyu was securely placed in Celia’s life, Celia liked to tell her friends how wonderfully clueless Ruyu had been. Who, if not Celia, would have driven one and a half hours to meet a potential nanny?

Why indeed had she agreed, Ruyu wanted to ask Celia sometimes, but the answer was not important, as what mattered was that Celia did go out of her way to meet Ruyu, and—this Ruyu had never doubted—if not Celia, there would be someone else willing to do the same.

When Celia arrived at Ruyu’s cottage, which, with its own garden and views of the canyon, would have been called “a gem” in a real estate ad, Celia could not hide her surprise and dismay. There was no way she could afford Ruyu, she said; all she had was an au pair’s suite on the first floor of her house.

But that would suit her well, Ruyu said, and explained that her employer was getting married in a few months, and she would like to move away before the wedding, since there was no reason for her to stay on as his housekeeper. Celia, Ruyu could see, was baffled by the relationship between the cottage and the three-storied colonial on the estate, which Celia must have seen while driving past—as well as that between Ruyu and Eric, whom Ruyu only referred to as her employer.

Curious, Celia later described the Chinese woman to Edwin; peculiar even, but all the same she was pleasant, clean, spoke perfect English, and deserved some help. Ruyu had not talked about the exact nature of her relationship with her employer, but Celia had guessed rightly that sex, with an agreement, was part of the employment. About other things in her background, Ruyu had been open with Celia during that first meeting: she had married her first husband at nineteen, a Chinese man who had been admitted to an American graduate school; she’d married him to leave China. Her second marriage, to an American, was to get herself a green card, which her first husband would have eventually helped her get, but she did not want to stay in the marriage for the five or six years it would have taken. She’d earned a bachelor’s degree in accounting from a state university and had worked on and off but never really built a career, which was fine with her because she did not like numbers or money. For the past three years, she’d been working as a housekeeper for her employer, and she was looking forward to moving on—no, she didn’t mean to marry again, Ruyu had said when Celia, out of curiosity, asked her if she was going to look for another husband; what she wanted, Ruyu said, was to find a job to support herself.

When Celia called again, a week later, she did not offer Ruyu the nanny position but said that she had found a cottage, furnished, which would be available for three months during the summer. Would Ruyu be open to taking it—she’d have to pay the three months’ rent up front—and working for Celia on a part-time basis? She would be happy to help Ruyu settle down, find her another cottage after the summer, and refer her to a few other families who could use Ruyu here and there. Without hesitation Ruyu had said yes.

The garage door opened, the noise reminding Ruyu of the immodest grumbling from inside one’s stomach. She was fascinated, even after years in America, by the intimate contract that sound confirmed: a door opens and then closes, yet through it neither departure nor arrival is damagingly permanent. Sitting in Celia’s kitchen and listening to her husband’s return, Ruyu allowed herself, for a brief moment, to imagine the possibility of such a life. Not a difficult task, in fact, as two men among the people of the world had offered her that—yet in the end, she was the one who had left. Had she stayed in either marriage she would have had to become one of those women in the living room, and the thought amused her. “Your problem,” Eric had said when she informed him of her moving plan only after finalizing it with Celia, “is that you don’t want enough. Though I suppose that also means things will always work out for you.”

Eric had been wise not to over-offer, as her two ex-husbands had, but he did indulge her, granting her all the space she needed, and making clear she should never feel bound in any way to him. Sometimes she wondered if, for that reason, she should have treated him better. But how does one treat a man better—by becoming more dependent on him, by asking more from him? All the same, what was the point of thinking of that now? A few years ago, Eric had made the local news for his involvement in a fundraising scandal during his campaign for assemblyman—so much for his wanting more.

Celia, who must have been listening also, took leave of the discussion and told Ruyu to show the T-shirts to the boys, her pitch a bit high because, Ruyu knew, of her nervousness about lying to her family. It was in these moments that Ruyu felt a tenderness toward Celia, who, despite her constant need for attention and her petty competition with her friends and neighbors, was, in the end, a woman with a good and weak heart.

A while later, with the boys in bed, Edwin came into the kitchen. In the living room, the women were still arguing about the best way to bring up a child to be competitive in a global market. A heated discussion today, he commented, and touched the stem of a wine glass before changing his mind. He poured water for himself.

Certainly Celia had chosen the right book, Ruyu said, and moved to the sink before Edwin sat down at the table. “I’ll start to put things away,” she said. “Celia has had a long day.”

Edwin asked if he could help, though Ruyu could tell it was a halfhearted offer. Probably all he wanted was for the women debating the future of American education to vacate his house. There was not much she needed him to do, Ruyu said. Edwin kept the conversation going, talking about trivialities—the Warriors’ win that night, a new movie Celia was talking about going to see that weekend, the Moorlands’ Thanksgiving plans, a bizarre report in the paper about a man impersonating a doctor and prescribing his only patient, an older woman, a regimen of eating watermelons in a hot tub. Ruyu wondered if Edwin was talking to her out of a sense of charity; she wished she could tell him that it was okay for him to treat her, at this or any other moment, like a piece of furniture or appliance in his well-kept house.