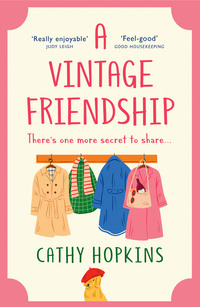

A Vintage Friendship

‘Mine would be Girl with a Bus Pass or Girl with a Hearing Aid.’

He sighed again. ‘Stop wallowing. How about you write a children’s book? Loads of celebrities are doing it—’

‘I can’t write,’ I pointed out.

‘You don’t always have to. Some of them use a ghost writer to do the bulk of the work then add their voice with a few tweaks at the end.’

I shook my head. ‘I haven’t a clue what children like to read now.’

‘That hasn’t stopped the others, and don’t forget you were a child once. What did you read to Elliott when he was small?’

‘Charles used to read him the Financial Times. That’s why he ended up in banking.’ Elliott is my son, currently living in New York.

Nicholas laughed. ‘Write one of those guide-to-life books, or how to entertain or decorate your house.’

‘No, thanks. It would be in the bargain-basement bin before you could say Pippa Middleton.’

‘Can you afford to take some time off? Think about things? Let me see what’s out there while you tread water for a while?’

‘I could for a few months, not more. I hadn’t planned for this, as you know. My divorce cleaned me out, then, before she died, Mum’s care-home costs ate up most of what was left of my income.’ My dear mum had suffered from dementia and had needed care for the last eight years of her life. I found her a fantastic place, not that she really knew where she was, or even who I was some days, but she was safe and looked after, with doctors and nurses on call twenty-four hours a day. It cost all her savings, just about everything I earned to keep her there, plus I’d remortgaged my house but I wouldn’t have had it any other way. No regrets. She died last year but, in truth, I’d lost the mother I’d known years before that.

‘You should have got more when you divorced Charles.’

‘I didn’t want his money. I just wanted to move on, not get caught in some lengthy battle between lawyers.’

Nicholas sighed. ‘He was the guilty party, so it wouldn’t have been a long battle. He didn’t deserve you. Many women in your situation would have taken him for everything he had.’

‘Not my style – anyway, let’s not talk about him.’.

Nicholas reached out and put his hand over mine. ‘Something will turn up. Careers have ups and downs; you’ve had to change direction before and you can do it again. Wait and see.’

Chapter Three

I did wait and see if Nicholas’s ‘something’ turned up. It didn’t. It was odd not having to get up, rush out, work long days.

I spent the first weeks hiding away, watching TV and reruns of Frasier and my all-time favourite, The Bonnets of Bath, a series about a group of feisty and funny friends in their sixties.

In the mornings, I had a few cursory glances over job opportunities advertised on the industry websites. Waste of time. Nothing for me. It was a younger person’s market, the openings were for people starting out, willing to do anything, go anywhere to get their foot in the door. I was over-qualified and too well known for anyone to hire me for what would appear to be a backwards step on the career path.

Nicholas called from time to time, sounding cheerful. ‘Nil desperandum. Chins up. I have a few meetings. I’ll let you know if anything comes of them; it’s got to be the right thing.’ He and James were great, supportive, cooking supper frequently and pouring the wine, but then they went off to the south of France for a week in early September and the phone went quiet.

Network, I thought, that’s what I must do. And I did.

Launches, lunches, I was willing to go to everything and not to hide away. My motto is to say yes to all invites, I told myself in an attempt to be positive. I went through my book of contacts, renewing acquaintances, people I’d worked with, people I swore I’d never work with again. It was obvious that many of them had heard that I was no longer with Calcot TV and no one had any openings.

A book launch party at The Ivy in Covent Garden was the last straw. With its dark wood interior and beautiful stained-glass windows, it was usually one of my favourite venues, but I could see people looking at me then turning away, whispering to friends who’d then look over. It wasn’t me being paranoid. That’s it, I decided. No more. I felt my inner Greta Garbo coming on and wanted to be alone.

I left early and hopped on the tube to get home. An elderly man kept staring at me. When he stood up to get off, he leant over. ‘Didn’t you used to be Sara Meyers?’ he asked.

‘I did,’ I replied.

*

At home, I went into my sitting room, lit a candle and flicked through my contact list to see if there was anyone I had missed. I knew I was lucky that I had such a place to come back to. Normally I am a positive person who likes a challenge but there was no doubt that my confidence had taken a knock and I was glad to have somewhere as lovely to retreat to. My shelter from the storm was a three-bedroom two-storey house with bi-folding doors at the back of the kitchen that opened out onto a small courtyard garden, presently alive with night-scented jasmine. Best of all, it was within walking distance of the cafés and shops in Notting Hill, so I never felt isolated. James had found it for me after Charles and I had split up and we’d sold our family home in Richmond. James’s mastermind subject is Rightmove, and both he and Nicholas advised that I go for the house, not only to live in, but as an investment. I’d decorated it in neutral colours and added texture in shades of pale lilac with linen and velvet cushions and soft wool throws. James, who worked as an art dealer (when he wasn’t looking at property porn), helped me choose rugs, artifacts and antiques to complement the look and stop it looking bland. It was a light and lovely space, but the truth was that I’d spent little time there over the last years. I was always either working or out most evenings. The house was comfy, uncluttered and tasteful but something was missing. I needed people on those stylish sofas, round the elegant dining table – friends, those dear ones you could turn to when the chips were down. The ones who had been with me through thick and thin, who knew me before I was Sara Meyers, celebrity. Where were they? And why weren’t they calling to commiserate?

In the many years my career had been booming, I’d lost touch with some of the good old folk I’d known for ever, so maybe they didn’t even know what had happened. As is the way for so many in the industry, I’d hung out with the people I worked with. I have 400K followers on Twitter, more on Instagram and my public Facebook page has thousands of likes. Supportive messages had been pouring in since the news of my leaving Carlton had hit some of the papers. Not that the press knew what had really happened. Sara Meyers is moving on, the journalists had said, and I’d played along with that with lots of jolly posts on social media about new opportunities beckoning. But were these cyber-followers my real friends? People I could confide my anxieties to? Never. Not in a million years.

Nicholas and James: there was no doubt they were great and kind friends. I spent Christmases with them, they made a fuss on my birthday, they took me with them sometimes when they holidayed in France, but I was aware that I was the singleton and they needed space and time alone as a couple as well.

Jo and Ally were the next who came to mind. My oldest friends from school days. We spoke on the phone or emailed but due to geography, distance and busy lives, now I only saw them once a year, if that. It was my fault, I knew; especially in the last decade, I’d put my career first at the expense of letting my friendship with them fade. I felt a sudden ache for what we’d had as girls when Mitch, the fourth member of our group, was still around too. When one of us felt down over a boy, or something that had happened at school or with a parent or sibling, it would be treated with the same seriousness as if we were facing the end of the world. We’d gather in whoever’s bedroom it was, bringing company and consolation, then maybe go into the sitting room and watch TV, listen to music or just talk it through, squashed on a sofa, our arms draped around each other. If at Jo’s, she’d make bowls of butterscotch Angel Delight or cheese toasties to take away the pain. Overall there was love, and I knew that each one of them had my back as I had theirs. I had no idea where Mitch was any more but I knew where Jo and Ally were. I could contact them, but they lived too far away to troop round as they used to and be sitting with me at my table half an hour later, plus it was probably unreasonable to call out of the blue after so long and expect things to be as they were.

I went to my computer, looked through my contacts list, and realized I had loads of ‘friends’ going back years: friends from work, friends from when Elliott was at school and from whom I grew apart once the shared bond of the school gate had gone; local friends in the neighbourhood who I liked but always felt I had to be on my best behaviour with. Those who ‘got me’, with whom I could completely be myself, were few and far between.

Anita Carling. My lovely friend from university days. Was. When she died, it broke my heart. We’d hit it off from the day we met and had stayed friends right to the end. She was like family to me, lived in London so we could always drop in on each other and her passing had left an almighty big hole. She would have been round in a flash, making me laugh, coming up with mad suggestions to retrain as a stripper or such like.

It was sobering when friends and family died and the familiar landscape of life shifted. My world had changed. Losing a close friend, and some time later my mum, had hit me hard. They say people deal with grief in different ways. Some weep until there are no more tears, others block it out. I went for distraction. I felt their loss daily, so took every opportunity to work or be occupied, accepting every invite to a party for a movie, art show, launch of a new play; anything to escape from the reality of Mum and Anita not being there any more.

Of course there were others. Lyn and Val. Friends from work. Both gone from London and despite promises to stay in touch, we hadn’t. Martha. Ah. A great mate for two decades when I was in my thirties and forties until a demanding and prestigious job took up her time. Jen Beecham? A strong older woman, a mentor for me when I first got into TV. She moved to the States over twelve years ago and although we FaceTimed, I needed someone in this country, preferably this city, even better in my street.

As I went down the list, I saw there were so many others I’d drifted apart from over the years. Jane Ewing. Susan Lewis. Erica Peters. Sophie Jenson and Karen Wood. Sandy Jenson. Josie. Caz, Suse, Alice, Kate – great fun, good-time girls. Hadn’t seen them in ages.

Friends. They can heal but also hurt. Some can build you up, support you and help you face the world, others can also bring you down and leave you wondering what happened. Friendships change, I thought, evolve. Some you outgrow, some have different expectations, some come to a hard and painful end – which brought me to Ruth. Another good friend for many years, up there with Anita, Jo and Ally. For a long time, she was one of my go-to people in a crisis, one of my share-everything girls, one of my thank-god-for-girlfriends type of pals. She was a petite woman with dark Spanish looks, although she was Sussex-born. I’d known her thirty years, since I started working in television and she was a casting director. We hit it off immediately, same sense of humour, same hang-ups, same liking for a good Chablis or two. She had a son, Ethan, the same age as Elliott, so as they’d grown we’d shared all the ups and downs of their childhood, teenage tantrums, exams, university days, getting them ready to fly the nest and then the emptiness when they’d gone.

When she lost her husband Brian to cancer just over ten years ago, I’d persuaded her to have a spa day, a bit of pampering to take her mind off probate and the endless tasks of the newly widowed. We were in the sauna when she gave me the news that ended our friendship.

Charles and I had been married for thirty years; in fact, it had been at a garden party at Ruth’s that I’d met him. They’d been friends since their university days, even dated, apparently. They both used to laugh it off but it was clear she adored him and I, fool that I was, didn’t think there was anything to worry about. Most people adored Charles. God, he was, is, a handsome man: tall, fair-haired, high forehead, aquiline nose. He could have been a lead actor with his looks. Women always stared at him in restaurants, on the street. I enjoyed that, proud to be seen with him. At home, he was a gentle man, considerate, easy to get along with. We were happy. He was my safe place. It was he who pursued me, wooed and won me, not that I put up much resistance. I knew straight off he was the One; there was an ease there, a sense of the familiar, a feeling of coming home as well as a strong physical attraction.

We soon settled into married life, did all the usual couple things: country weekends with friends. He met and got on well with Ally and Jo and their husbands. We went to farmers’ markets on Saturdays, walks by the river on Sundays, cooked for each other, talked a lot about books, politics, life, made each other laugh. I was sure he’d always be there for me, as I was for him. We liked each other, looked out for each other. We had history, had seen each other through the death of my father fifteen years ago, and then his a year later. We had done exactly what the marriage vow says – for richer and poorer, better and worse – and, of course, we had Elliott, who’d sealed and strengthened our bond from the moment he was conceived. OK, the sex had faded a little (a lot) towards the end, but didn’t it with all couples? We even bought a book with exercises to do at home to resurrect the passion, but then agreed it didn’t matter, we had plenty of other things going for us. The bottom line was that he was my best friend, and I his.

Ruth and I were talking about a mutual friend, whose husband had had an affair. One morning he’d come down and told her that he no longer loved her and was leaving her for a work colleague, a woman who looked just like her, only fifteen years younger. She was devastated, and I was saying that we should be there for her, take her out, be supportive friends, when I noticed Ruth had gone quiet.

‘Look … no easy way to say this. I’ve been having one with Charles,’ she blurted. I laughed. She didn’t. ‘No seriously, Sara, for five years. We’ve been waiting for the right moment to tell you, but of course there never is one.’

I studied her face, puzzled as to where this bizarre claim was coming from. We’d been on holiday with her and Brian many times. We were close. I knew all her secrets, didn’t I? She went on to fill me in on more details. I listened, not taking it in. Five years? That meant it had started when Brian was still alive, before he got ill. It couldn’t possibly be true but it was. I got home that evening to find Charles had already packed his bags. ‘I am sorry,’ he said. ‘I never wanted to hurt you.’

For once in my life, I was speechless.

After he’d gone, I knelt on the floor in front of his empty wardrobe and howled like a wounded animal. Nothing had ever hurt so much. As deep as grief but a different kind of loss. He was still alive but gone from my life. I’d always thought Charles was mine. My husband, my go-to person, pick me up at the station ride, accompany me to a hospital scan and be there in the waiting room, holiday companion, my mow the lawn, take out the bins man, presence in the bed next to me, person to look over at and smile at a funny moment on TV, man to tell a piece of news or gossip to, put his feet on my knee for a foot massage. Part of my life. All my life. Always been there and would be until death do us part. My husband.

Not any more. The shock was overwhelming. I hadn’t seen it coming, hadn’t suspected, not for a moment. I’d left them alone so many times. Why wouldn’t I? We were all such good friends. I’d trusted him, and her. But then it made sense – Ruth’s over-concern when Charles was unwell. I’d been touched by it. Her defence of him on the odd day I was having a groan. She always took his side. I’d thought it was her just trying to show me what a good marriage I had. And it was good. I knew he loved and liked me. Was it the sex? I pushed away the mental picture of him making love to Ruth. The thought made me ill but of course it was there – what did she offer that I didn’t? Adoration? Notable appreciation of him? Probably. Perhaps I’d taken what we had for granted, not expressed my true feelings enough and had expected him to know how I felt? Company? She didn’t work the hours I did but Charles, who was also in the TV industry, albeit behind the camera, had always seemed to understand, even support me in the demands my job made. ‘I’ll be here with a cooked meal when you get back,’ he’d often say when I was away from home a lot. He could have been the one that pushed and climbed the career ladder, even been a director, but he never had the ambition, he was a team player rather than a leader, a man who said he preferred a simpler, quieter life. He was my rock. My place to return to. Although … as a cameraman, there had been occasions when he’d had to be away shooting a programme. As Ruth made her confession, I began to wonder if he actually had been working all those times.

So, Ruth as a person, a friend to call at this moment of crisis in my life. I think not.

Sara Meyers. Me. What kind of friend had I been to some of these people? A good one at times, I liked to think, but a distant one who hadn’t made the effort in the past years, so basically a pretty crap one. I used to value my friendships highly, had rules I tried to adhere to about staying in touch, being there for the ones I cared for but I’d fallen short of my own standards. No regrets? That was usually one of my mottos but I did have regrets: I regretted that Mum had gone. Before her illness took hold, we used to have long chats about our lives, hopes, relationships, news, books and gossip. Although there physically for many years before she died, the mother I knew disappeared to the point she didn’t recognize me any more and often thought I was her sister. I missed the woman she had been – capable, curious and engaged with the world. I missed her maternal care and concern.

That Anita had died. She was still alive when Charles left and was there with endless support and sympathy, as I was for her through her illness. It was our unspoken code that we had each other’s backs.

Charles, also gone. When we were together, our table had always been full of mutual friends for long Sunday lunches, summer barbecues, cosy winter suppers. We made a good team, sharing the shopping, him doing the mains, me on starters and puddings. When he left, friends divided like guests at a wedding, taking sides – his and hers – and I lost the heart for entertaining. It never felt the same.

Three of the closest people to me had gone from my life in a decade and a part of me had closed off, unable to deal with the reality of losing those I had loved and being left behind.

Ally and Jo were still there, good friends and, though not in London, not really too far away. I should make a lot more effort to stay in touch.

So regrets, yes, I have a few, as the song goes. I could see, looking back, that I had hardly been the model friend, maybe not even the model wife. There were times when I’d done that typical TV personality trick of disappearing up my own backside. How were my next chapters going to be as I sailed into my late sixties, seventies and eighties and didn’t have the distraction of work? And no real pals to hang out with? I didn’t want to be alone, and yet who would be there for company and care? To laugh and cry with? I sensed a tsunami of gloom about to rise up and consume me, so I did what I often do when doom threatens. I got out my laptop, found a ‘dance along to Bollywood’ clip, pressed play and shimmied round the sitting room for ten minutes. Despite the uplifting music, though, I couldn’t escape the underlying feeling that I’d made a mess. I was in my sixties and a Billy No-mates. Friendship is a two-way street, one of my old rules, I reminded myself. Both make equal effort. You get in touch, they get in touch. I should do just that. True friends don’t let distance or work get in the way, so I should pick up the phone and let those I care about know that I’m still here and haven’t forgotten them.

Chapter Four

‘Some of those people weren’t your real friends,’ said Nicholas the next day, after we’d caught up with our news. ‘Plus people grow apart, move on when you find you suddenly have nothing in common any more. Sometimes it’s not personal.’

We were sitting at a popular breakfast spot just off Ladbroke Grove, enjoying the autumn sunshine on an outside table where we could people-watch as well as chat.

‘Yes but thinking about various friendships and why we’re no longer close, I know some of it has been my fault.’

‘Then do something about it. It was tough for you to lose one of your best friends to illness and another to—’

‘Charles.’

‘To Charles, and OK, so you don’t currently have a Thelma to your Louise, but you’ve got the time now, you can start again.’

‘Thank god for you,’ I replied. ‘At least you like me.’

He made a mock-puzzled face. ‘Whatever gave you that idea?’ he asked, then laughed. ‘What about your brothers?’

It was my turn to laugh. ‘Patrick and Henry? Not people to turn to in a time of crisis, and anyway, they live so far away. Henry’s in Norfolk and Patrick is in Iverness. It’s very much a one-way street – you know what it’s like with blokes. I call them and we have a catch-up at Christmas and birthday and that’s about it.’

Nicholas sighed. ‘That’s why friends are essential. As the saying goes, they are the family you choose. Old friends then? What about those school friends I’ve heard you talk about?’

‘Jo, Ally and Mitch. I was thinking about them the other night – well, Jo and Ally anyway, I have no idea where Mitch is now.’

‘What happened to them? Where are they now?’

‘Jo’s in Wiltshire, Ally in Devon. Jo has a big family and menagerie of animals living with her. Ally married her soul mate. We’ve been through phases, sometimes seeing little of each other then a lot then less again. After Charles left, I was the single one, I guess that changed things a fair bit, for me anyway.’

‘You’ve been very focused, had a fantastic career, not many people can say that.’

‘True and I worked hard to get where I am but success could be problematic sometimes.’

‘How so?’

‘Earning more than some friends, being able to eat out in nice places. Do I offer to pay or is that patronizing?’

‘Was that a problem with Ally and Jo?’

‘There was a time I was earning a lot more than them. One year I bought them expensive gifts at Christmas, lovely things. I wanted to. It made me feel really happy to spoil them both a little and share my good fortune. The next year Ally suggested we had a limit and not to go over it because Jo had felt she couldn’t match my presents and she had so many of her own family to buy for. But then, she gave gorgeous things like home-made chutney or jam. I’d loved getting her presents. It cast a cloud over the whole gift-giving caboodle so in the end we just stopped completely.’

‘You could have talked it through.’

‘I could have. I should have. They’re my oldest friends and probably would have teased me about it, told me to get over myself and that would have been the end of it.’

‘It’s good to agree on a figure for gifts sometimes, makes it easier all round or do Secret Santa. They both worked, didn’t they?’

‘Oh yes, they had careers too. Jo was always a great cook, had her own café, deli and farm shop for a while. She was struggling in the early days but she’s more comfortable now as her parents left her a tidy sum. Ally went into publishing then became a literary agent. Her and her husband were quite the golden couple. He’s a very successful writer—’