Old-Time Gardens, Newly Set Forth

I do not doubt that this Van Cortlandt garden was laid out when the house was built; much of it must be two centuries old. It has been extended, not altered; and the grass-covered bank supporting the upper garden was replaced by a brick terrace wall about sixty years ago. Its present form dates to the days when New York was a province. The upper garden is laid out in formal flower beds; the lower border is rich in old vines and shrubs, and all the beloved old-time hardy plants. There is in the manor-house an ancient portrait of the child Pierre Van Cortlandt, painted about the year 1732. He stands by a table bearing a vase filled with old garden flowers – Tulip, Convolvulus, Harebell, Rose, Peony, Narcissus, and Flowering Almond; and it is the pleasure of the present mistress of the manor, to see that the garden still holds all the great-grandfather's flowers.

There is a vine-embowered old door in the wall under the piazza (see opposite page 20) which opens into the kitchen and fruit garden; a wall-door so quaint and old-timey that I always remind me of Shakespeare's lines in Measure for Measure: —

"He hath a garden circummured with brick,Whose western side is with a Vineyard back'd;And to that Vineyard is a planchéd gateThat makes his opening with this bigger key:The other doth command a little doorWhich from the Vineyard to the garden leads."The long path is a beautiful feature of this garden (it is shown in the picture of the garden opposite page 24); it dates certainly to the middle of the eighteenth century. Pierre Van Cortlandt, the son of the child with the vase of flowers, and grandfather of the present generation bearing his surname, was born in 1762. He well recalled playing along this garden path when he was a child; and that one day he and his little sister Ann (Mrs. Philip Van Rensselaer) ran a race along this path and through the garden to see who could first "see the baby" and greet their sister, Mrs. Beekman, who came riding to the manor-house up the hill from Tarrytown, and through the avenue, which shows on the right-hand side of the garden-picture. This beautiful young woman was famed everywhere for her grace and loveliness, and later equally so for her intelligence and goodness, and the prominent part she bore in the War of the Revolution. She was seated on a pillion behind her husband, and she carried proudly in her arms her first baby (afterward Dr. Beekman) wrapped in a scarlet cloak. This is one of the home-pictures that the old garden holds. Would we could paint it!

In this garden, near the house, is a never failing spring and well. The house was purposely built near it, in those days of sudden attacks by Indians; it has proved a fountain of perpetual youth for the old Locust tree, which shades it; a tree more ancient than house or garden, serene and beautiful in its hearty old age. Glimpses of this manor-house garden and its flowers are shown on many pages of this book, but they cannot reveal its beauty as a whole – its fine proportions, its noble background, its splendid trees, its turf, its beds of bloom. Oh! How beautiful a garden can be, when for two hundred years it has been loved and cherished, ever nurtured, ever guarded; how plainly it shows such care!

Another Dutch garden is pictured opposite page 32, the garden of the Bergen Homestead, at Bay Ridge, Long Island. Let me quote part of its description, written by Mrs. Tunis Bergen: —

"Over the half-open Dutch door you look through the vines that climb about the stoop, as into a vista of the past. Beyond the garden is the great Quince orchard of hundreds of trees in pink and white glory. This orchard has a story which you must pause in the garden to hear. In the Library at Washington is preserved, in quaint manuscript, 'The Battle of Brooklyn,' a farce written and said to have been performed during the British occupation. The scene is partly laid in 'the orchard of one Bergen,' where the British hid their horses after the battle of Long Island – this is the orchard; but the blossoming Quince trees tell no tale of past carnage. At one side of the garden is a quaint little building with moss-grown roof and climbing hop-vine – the last slave kitchen left standing in New York – on the other side are rows of homely beehives. The old Locust tree overshadowing is an ancient landmark – it was standing in 1690. For some years it has worn a chain to bind its aged limbs together. All this beauty of tree and flower lived till 1890, when it was swept away by the growing city. Though now but a memory, it has the perfume of its past flowers about it."

The Locust was so often a "home tree" and so fitting a one, that I have grown to associate ever with these Dutch homesteads a light-leaved Locust tree, shedding its beautiful flickering shadows on the long roof. I wonder whether there was any association or tradition that made the Locust the house-friend in old New York!

The first nurseryman in the new world was stern old Governor Endicott of Salem. In 1644 he wrote to Governor Winthrop, "My children burnt mee at least 500 trees by setting the ground on fire neere them" – which was a very pretty piece of mischief for sober Puritan children. We find all thoughtful men of influence and prominence in all the colonies raising various fruits, and selling trees and plants, but they had no independent business nurseries.

If tradition be true, it is to Governor Endicott we owe an indelible dye on the landscape of eastern Massachusetts in midsummer. The Dyer's-weed or Woad-waxen (Genista tinctoria), which, in July, covers hundreds of acres in Lynn, Salem, Swampscott, and Beverly with its solid growth and brilliant yellow bloom, is said to have been brought to this country as the packing of some of the governor's household belongings. It is far more probable that he brought it here to raise it in his garden for dyeing purposes, with intent to benefit the colony, as he did other useful seeds and plants. Woadwaxen, or Broom, is a persistent thing; it needs scythe, plough, hoe, and bitter labor to eradicate it. I cannot call it a weed, for it has seized only poor rock-filled land, good for naught else; and the radiant beauty of the Salem landscape for many weeks makes us forgive its persistence, and thank Endicott for bringing it here.

"The Broom,Full-flowered and visible on every steep,Along the copses runs in veins of gold."The Broom flower is the emblem of mid-summer, the hottest yellow flower I know – it seems to throw out heat. I recall the first time I saw it growing; I was told that it was "Salem Wood-wax." I had heard of "Roxbury Waxwork," the Bitter-sweet, but this was a new name, as it was a new tint of yellow, and soon I had its history, for I find Salem people rather proud both of the flower and its story.

Oxeye Daisies (Whiteweed) are also by vague tradition the children of Governor Endicott's planting. I think it far more probable that they were planted and cherished by the wives of the colonists, when their beloved English Daisies were found unsuited to New England's climate and soil. We note the Woad-waxen and Whiteweed as crowding usurpers, not only because they are persistent, but because their great expanses of striking bloom will not let us forget them. Many other English plants are just as determined intruders, but their modest dress permits them to slip in comparatively unobserved.

It has ever been characteristic of the British colonist to carry with him to any new home the flowers of old England and Scotland, and characteristic of these British flowers to monopolize the earth. Sweetbrier is called "the missionary-plant," by the Maoris in New Zealand, and is there regarded as a tiresome weed, spreading and holding the ground. Some homesick missionary or his more homesick wife bore it there; and her love of the home plant impressed even the savage native. We all know the story of the Scotch settlers who carried their beloved Thistles to Tasmania "to make it seem like home," and how they lived to regret it. Vancouver's Island is completely overrun with Broom and wild Roses from England.

The first commercial nursery in America, in the sense of the term as we now employ it, was established about 1730 by Robert Prince, in Flushing, Long Island, a community chiefly of French Huguenot settlers, who brought to the new world many French fruits by seed and cuttings, and also a love of horticulture. For over a century and a quarter these Prince Nurseries were the leading ones in America. The sale of fruit trees was increased in 1774 (as we learn from advertisements in the New York Mercury of that year), by the sale of "Carolina Magnolia flower trees, the most beautiful trees that grow in America, and 50 large Catalpa flower trees; they are nine feet high to the under part of the top and thick as one's leg," also other flowering trees and shrubs.

The fine house built on the nursery grounds by William Prince suffered little during the Revolution. It was occupied by Washington and afterwards house and nursery were preserved from depredations by a guard placed by General Howe when the British took possession of Flushing. Of course, domestic nursery business waned in time of war; but an excellent demand for American shrubs and trees sprung up among the officers of the British army, to send home to gardens in England and Germany. Many an English garden still has ancient plants and trees from the Prince Nurseries.

The "Linnæan Botanic Garden and Nurseries" and the "Old American Nursery" thrived once more at the close of the war, and William Prince the second entered in charge; one of his earliest ventures of importance was the introduction of Lombardy Poplars. In 1798 he advertises ten thousand trees, ten to seventeen feet in height. These became the most popular tree in America, the emblem of democracy – and a warmly hated tree as well. The eighty acres of nursery grounds were a centre of botanic and horticultural interest for the entire country; every tree, shrub, vine, and plant known to England and America was eagerly sought for; here the important botanical treasures of Lewis and Clark found a home. William Prince wrote several notable horticultural treatises; and even his trade catalogues were prized. He established the first steamboats between Flushing and New York, built roads and bridges on Long Island, and was a public-spirited, generous citizen as well as a man of science. His son, William Robert Prince, who died in 1869, was the last to keep up the nurseries, which he did as a scientific rather than a commercial establishment. He botanized the entire length of the Atlantic States with Dr. Torrey, and sought for collections of trees and wild flowers in California with the same eagerness that others there sought gold. He was a devoted promoter of the native silk industry, having vast plantations of Mulberries in many cities; for one at Norfolk, Virginia, he was offered $100,000. It is a curious fact that the interest in Mulberry culture and the practice of its cultivation was so universal in his neighborhood (about the year 1830), that cuttings of the Chinese Mulberry (Morus multicaulis) were used as currency in all the stores in the vicinity of Flushing, at the rate of 12½ cents each.

The Prince homestead, a fine old mansion, is here shown; it is still standing, surrounded by that forlorn sight, a forgotten garden. This is of considerable extent, and evidences of its past dignity appear in the hedges and edgings of Box; one symmetrical great Box tree is fifty feet in circumference. Flowering shrubs, unkempt of shape, bloom and beautify the waste borders each spring, as do the oldest Chinese Magnolias in the United States. Gingkos, Paulownias, and weeping trees, which need no gardener's care, also flourish and are of unusual size. There are some splendid evergreens, such as Mt. Atlas Cedars; and the oldest and finest Cedar of Lebanon in the United States. It seemed sad, as I looked at the evidences of so much past beauty and present decay, that this historic house and garden should not be preserved for New York, as the house and garden of John Bartram, the Philadelphia botanist, have been for his native city.

While there are few direct records of American gardens in the eighteenth century, we have many instructing side glimpses through old business letter-books. We find Sir Harry Frankland ordering Daffodils and Tulips for the garden he made for Agnes Surriage; and it is said that the first Lilacs ever seen in Hopkinton were planted by him for her. The gay young nobleman and the lovely woman are in the dust, and of all the beautiful things belonging to them there remain a splendid Portuguese fan, which stands as a memorial of that tragic crisis in their life – the great Lisbon earthquake; and the Lilacs, which still mark the site of her house and blossom each spring as a memorial of the shadowed romance of her life in New England.

Let me give two pages from old letters to illustrate what I mean by side glimpses at the contents of colonial gardens. The fine Hancock mansion in Boston had a carefully-filled garden long previous to the Revolution. Such letters as the following were sent by Mr. Hancock to England to secure flowers for it: —

"My Trees and Seeds for Capt. Bennett Came Safe to Hand and I like them very well. I Return you my hearty Thanks for the Plumb Tree and Tulip Roots you were pleased to make me a Present off, which are very Acceptable to me. I have Sent my friend Mr. Wilks a mmo. to procure for me 2 or 3 Doz. Yew Trees, Some Hollys and Jessamine Vines, and if you have Any Particular Curious Things not of a high Price, will Beautifye a flower Garden Send a Sample with the Price or a Catalogue of 'em, I do not intend to spare Any Cost or Pains in making my Gardens Beautifull or Profitable.

"P.S. The Tulip Roots you were Pleased to make a present off to me are all Dead as well."

We find Richard Stockton writing in 1766 from England to his wife at their beautiful home "Morven," in Princeton, New Jersey: —

"I am making you a charming collection of bulbous roots, which shall be sent over as soon as the prospect of freezing on your coast is over. The first of April, I believe, will be time enough for you to put them in your sweet little flower garden, which you so fondly cultivate. Suppose I inform you that I design a ride to Twickenham the latter end of next month principally to view Mr. Pope's gardens and grotto, which I am told remain nearly as he left them; and that I shall take with me a gentleman who draws well, to lay down an exact plan of the whole."

The fine line of Catalpa trees set out by Richard Stockton, along the front of his lawn, were in full flower when he rode up to his house on a memorable July day to tell his wife that he had signed the Declaration of American Independence. Since then Catalpa trees bear everywhere in that vicinity the name of Independence trees, and are believed to be ever in bloom on July 4th.

In the delightful diary and letters of Eliza Southgate Bowne (A Girl's Life Eighty Years Ago), are other side glimpses of the beautiful gardens of old Salem, among them those of the wealthy merchants of the Derby family. Terraces and arches show a formality of arrangement, for they were laid out by a Dutch gardener whose descendants still live in Salem. All had summer-houses, which were larger and more important buildings than what are to-day termed summer-houses; these latter were known in Salem and throughout Virginia as bowers. One summer-house had an arch through it with three doors on each side which opened into little apartments; one of them had a staircase by which you could ascend into a large upper room, which was the whole size of the building. This was constructed to command a fine view, and was ornamented with Chinese articles of varied interest and value; it was used for tea-drinkings. At the end of the garden, concealed by a dense Weeping Willow, was a thatched hermitage, containing the life-size figure of a man reading a prayer-book; a bed of straw and some broken furniture completed the picture. This was an English fashion, seen at one time in many old English gardens, and held to be most romantic. Apparently summer evenings were spent by the Derby household and their visitors wholly in the garden and summer-house. The diary keeper writes naïvely, "The moon shines brighter in this garden than anywhere else."

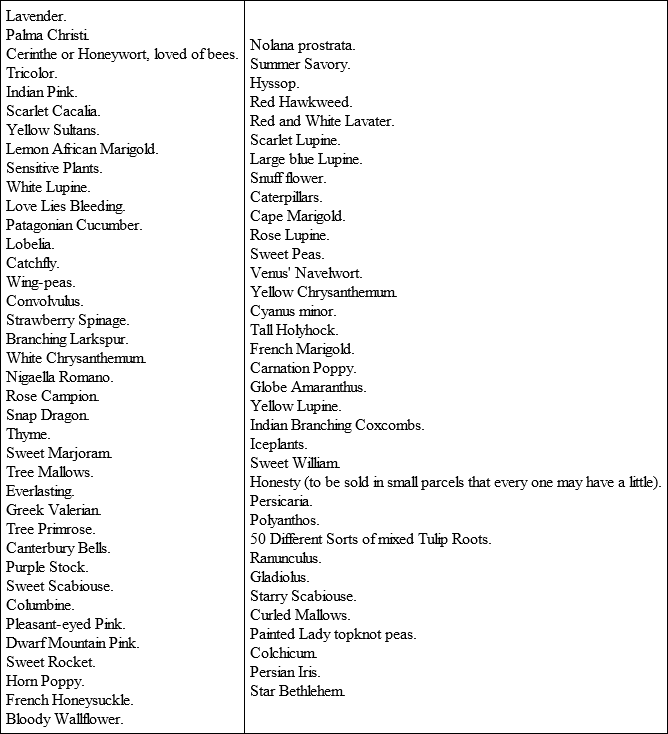

The shrewd and capable women of the colonies who entered so freely and successfully into business ventures found the selling of flower seeds a congenial occupation, and often added it to the pursuit of other callings. I think it must have been very pleasant to buy packages of flower seed at the same time and place where you bought your best bonnet, and have all sent home in a bandbox together; each would prove a memorial of the other; and long after the glory of the bonnet had departed, and the bonnet itself was ashes, the thriving Sweet Peas and Larkspur would recall its becoming charms. I have often seen the advertisements of these seedswomen in old newspapers; unfortunately they seldom gave printed lists of their store of seeds. Here is one list printed in a Boston newspaper on March 30, 1760: —

This list is certainly a pleasing one. It gives opportunity for flower borders of varied growth and rich color. There is a quality of some minds which may be termed historical imagination. It is the power of shaping from a few simple words or details of the faraway past, an ample picture, full of light and life, of which these meagre details are but a framework. Having this list of the names of these sturdy old annuals and perennials, what do you perceive besides the printed words? I see that the old mid-century garden where these seeds found a home was a cheerful place from earliest spring to autumn; that it had many bulbs, and thereafter a constant succession of warm blooms till the Coxcombs, Marigolds, Colchicums and Chrysanthemums yielded to New England's frosts. I know that the garden had beehives and that the bees were loved; for when they sallied out of their straw bee-skepes, these happy bees found their favorite blossoms planted to welcome them: Cerinthe, dropping with honey; Cacalia, a sister flower; Lupine, Larkspur, Sweet Marjoram, and Thyme – I can taste the Thyme-scented classic honey from that garden! There was variety of foliage as well as bloom, the dovelike Lavender, the glaucous Horned Poppy, the glistening Iceplants, the dusty Rose Campion.

Stately plants grew from the little seed-packets; Hollyhocks, Valerian, Canterbury Bells, Tree Primroses looked down on the low-growing herbs of the border; and there were vines of Convolvulus and Honeysuckle. It was a garden overhung by clouds of perfume from Thyme, Lavender, Sweet Peas, Pleasant-eyed Pink, and Stock. The garden's mistress looked well after her household; ample store of savory pot herbs grow among the finer blossoms.

It was a garden for children to play in. I can see them; little boys with their hair tied in queues, in knee breeches and flapped coats like their stately fathers, running races down the garden path, as did the Van Cortlandt children; and demure little girls in caps and sacques and aprons, sitting in cubby houses under the Lilac bushes. I know what flowers they played with and how they played, for they were my great-grandmothers and grandfathers, and they played exactly what I did, and sang what I did when I was a child in a garden. And suddenly my picture expands, as a glow of patriotic interest thrills me in the thought that in this garden were sheltered and amused the boys of one hundred and forty years ago, who became the heroes of our American Revolution; and the girls who were Daughters of Liberty, who spun and wove and knit for their soldiers, and drank heroically their miserable Liberty tea. I fear the garden faded when bitter war scourged the land, when the women turned from their flower beds to the plough and the field, since their brothers and husbands were on the frontier.

But when that winter of gloom to our country and darkness to the garden was ended, the flowers bloomed still more brightly, and to the cheerful seedlings of the old garden is now given perpetual youth and beauty; they are fated never to grow faded or neglected or sad, but to live and blossom and smile forever in the sunshine of our hearts through the magic power of a few printed words in a time-worn old news-sheet.

CHAPTER II

FRONT DOORYARDS

"There are few of us who cannot remember a front yard garden which seemed to us a very paradise in childhood. Whether the house was a fine one and the enclosure spacious, or whether it was a small house with only a narrow bit of ground in front, the yard was kept with care, and was different from the rest of the land altogether… People do not know what they lose when they make way with the reserve, the separateness, the sanctity, of the front yard of their grandmothers. It is like writing down family secrets for any one to read; it is like having everybody call you by your first name, or sitting in any pew in church."

– Country Byways, Sarah Orne Jewett, 1881.Old New England villages and small towns and well-kept New England farms had universally a simple and pleasing form of garden called the front yard or front dooryard. A few still may be seen in conservative communities in the New England states and in New York or Pennsylvania. I saw flourishing ones this summer in Gloucester, Marblehead, and Ipswich. Even where the front yard was but a narrow strip of land before a tiny cottage, it was carefully fenced in, with a gate that was kept rigidly closed and latched. There seemed to be a law which shaped and bounded the front yard; the side fences extended from the corners of the house to the front fence on the edge of the road, and thus formed naturally the guarded parallelogram. Often the fence around the front yard was the only one on the farm; everywhere else were boundaries of great stone walls; or if there were rail fences, the front yard fence was the only painted one. I cannot doubt that the first gardens that our foremothers had, which were wholly of flowering plants, were front yards, little enclosures hard won from the forest.

The word yard, not generally applied now to any enclosure of elegant cultivation, comes from the same root as the word garden. Garth is another derivative, and the word exists much disguised in orchard. In the sixteenth century yard was used in formal literature instead of garden; and later Burns writes of "Eden's bonnie yard, Where yeuthful lovers first were pair'd."

This front yard was an English fashion derived from the forecourt so strongly advised by Gervayse Markham (an interesting old English writer on floriculture and husbandry), and found in front of many a yeoman's house, and many a more pretentious house as well in Markham's day. Forecourts were common in England until the middle of the eighteenth century, and may still be seen. The forecourt gave privacy to the house even when in the centre of a town. Its readoption is advised with handsome dwellings in England, where ground-space is limited, – and why not in America, too?

The front yard was sacred to the best beloved, or at any rate the most honored, garden flowers of the house mistress, and was preserved by its fences from inroads of cattle, which then wandered at their will and were not housed, or even enclosed at night. The flowers were often of scant variety, but were those deemed the gentlefolk of the flower world. There was a clump of Daffodils and of the Poet's Narcissus in early spring, and stately Crown Imperial; usually, too, a few scarlet and yellow single Tulips, and Grape Hyacinths. Later came Phlox in abundance – the only native American plant, – Canterbury Bells, and ample and glowing London Pride. Of course there were great plants of white and blue Day Lilies, with their beautiful and decorative leaves, and purple and yellow Flower de Luce. A few old-fashioned shrubs always were seen. By inflexible law there must be a Lilac, which might be the aristocratic Persian Lilac. A Syringa, a flowering Currant, or Strawberry bush made sweet the front yard in spring, and sent wafts of fragrance into the house-windows. Spindling, rusty Snowberry bushes were by the gate, and Snowballs also, or our native Viburnums. Old as they seem, the Spiræas and Deutzias came to us in the nineteenth century from Japan; as did the flowering Quinces and Cherries. The pink Flowering Almond dates back to the oldest front yards (see page 39), and Peter's Wreath certainly seems an old settler and is found now in many front yards that remain. The lovely full-flowered shrub of Peter's Wreath, on page 41, which was photographed for this book, was all that remained of a once-loved front yard.