One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time

Fox Photos/Stringer

35

Towards the end of 1963, the sanity of the younger generation was being called into question. ‘Many young people these days complain that adults tend to condemn them,’ wrote one irate newspaper reader. ‘But when one sees the disgusting behaviour now occurring up and down the country under the name of “Beatlemania” it is impossible not to draw certain conclusions.’

A columnist in York’s Evening Press echoed this sentiment: ‘Ask any teenager in York and they could name the four Beatles. Now ask those same teenagers for the names of a few other well-known personalities. The Secretary General of the United Nations, for example, or even our own Prime Minister. The answers, in many cases, will not slip so easily off the tongue. Such is fame. Such is our sense of values in the modern world.’ That same columnist, the aptly-named John Blunt, decried ‘the howling, screaming, bustling, shoving, fighting mobs which collect whenever they make an appearance’.

Throughout the Beatles’ tour of the UK, reporters struggled to describe the sound of thousands of adolescents screaming at the top of their voices. ‘I have not attended the mass torture or execution of 5000 assorted farmyard animals,’ wrote the Newcastle Journal’s reporter Rodney Pybus. ‘But I imagine the noise they would make would be very similar to that which forced my fingertips deep into my ears.’ Other newspapers roped in tame psychologists to dig deeper in the hope of uncovering the source of this mayhem. ‘This is not really hysteria. Hysteria is pathological. It is a disease,’ concluded Professor John Cohen, the head of the Psychology Department at Manchester University. To the central question – why do the girls scream? – he drew a blank: ‘You might as well ask a flock of geese why they fly and flap their wings.’ At the Beatles’ concert in the Southend Odeon on 9 December, a policeman armed with a noise meter recorded the screaming at 110 decibels, the equal of a sustained artillery barrage.

The American journalist Michael Braun accompanied the Beatles to the Cambridge Regal on 26 November. At that same venue the previous March the group had supported ‘America’s Exciting’ Chris Montez and ‘America’s Fabulous’ Tommy Roe. But now it was they who were being supported by others. Fans had been queuing in the streets outside the Regal since 10.30 a.m. By 6 p.m. the line was already half a mile long. Hours before the show, the Beatles had met the police at an agreed spot a mile away, to be smuggled into the theatre in the back of a police van.

When I was a child, whenever we went to the cinema in Dorking, or the pantomime in Leatherhead, ‘God Save the Queen’ would be played before and after each show. As if by magic, the audience would rise from their seats and stand to attention until the patriotic strains were finally exhausted. When the National Anthem was played at the start of the Beatles’ Cambridge show, Michael Braun witnessed not a hint of rebellion. But then again, there were plenty of unscream-at-able support acts to get through before the Beatles were due on, among them Peter Jay and the Jaywalkers, the Vernon Girls and the Brook Brothers. But the second the Beatles were announced the audience burst into high-pitched screams that continued right up to the strumming of the final chord of ‘Twist and Shout’. ‘Some girls are now waving handkerchiefs,’ wrote Braun. ‘Others are sitting in a foetal position: back arched, legs folded under, and hands alternately punching their thighs and covering their ears. Most of the boys just keep their hands over their ears.’

Braun watched a girl in an aisle seat crying every time the lights went up and down. At the end, after ‘Twist and Shout’, she stood on her seat screaming and crying until the National Anthem began to play over the house speakers. At that moment, in common with all the other girls, she stopped screaming and stood stock-still. But the second it drew to a close – Gar-aar-ard Say-aay-aayve the Quee-eee-eeen! – they all started screaming again.1

This peculiar pattern was repeated throughout the Beatles’ tour of Britain. Stewards at these shows tended to be middle-aged and hard-done-by, temperamentally ill-suited to extracting enjoyment from youthful exuberance. At the show in Leicester’s De Montfort Hall on 1 December, police and stewards were supplied with cotton wool to protect their ears. The fifty-nine-year-old Ray Millward complained that he had been kicked and punched by a delirious female fan: ‘We used to get a lot of hysteria with Cliff Richard, but this beats everything. I had a shoe and an umbrella thrown at me. One girl fought like a wildcat. I had to force her arm behind her back to get her to sit down. She was scratching, kicking and screaming.’ Jelly babies – which, in an offhand moment, the Beatles had said they enjoyed – were now being hurled at them from every corner, even though the group had publicly protested that they would prefer it if they weren’t. Misunderstanding them, some girls started throwing full boxes of chocolates instead. Autograph books, a doll and a giant panda were also hurled. Despite this pandemonium, the fans still stood stock-still for the National Anthem, a godsend from the Beatles’ point of view, as it gave them plenty of time to make a speedy getaway through the stage door to their waiting Austin Princess. Meanwhile their fans remained inside, rooted to the spot out of respect for Her Majesty.

That November, as the Queen Mother, Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon arrived at the Prince of Wales theatre for the Royal Command Performance, they were greeted by crowds chanting ‘We Want the Beatles!’ At that moment, it must have dawned on them that, like so many other long-established groups that year, they too had just been downgraded to a support act.

Taking his seat in the audience, Brian Epstein was nervous. Could he trust John to behave? The day before, John had worked out a cheeky joke for introducing their final song, ‘Twist and Shout’: ‘For our last number, I’d like to ask your help. Would the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands. And the rest of you, if you’d just rattle your jewellery.’ It was already slightly edgy, but in the dress rehearsal John had made it a good deal edgier by saying ‘rattle your fucking jewellery’. To Epstein’s relief, when the big moment came John omitted the expletive, and even added a chummy thumbs-up to show it was only a joke. In their black ties and evening dresses, the audience burst into laughter and applause.

After the show, the Beatles were presented to the Queen Mother. Or – given society’s new priorities – was it the Queen Mother who was presented to the Beatles? She had, she said, very much enjoyed herself. And where would they be performing next? Slough, came the answer. ‘Oh, that’s near us,’ she replied.

The next day’s newspapers were full of the Beatles. Devoting an editorial to their triumph, the working-class Daily Mirror welcomed the revolution:

Fact is that Beatle People are everywhere. From Wapping to Windsor. Aged seven to seventy. And it’s plain to see why these four cheeky, energetic lads from Liverpool go down so big.

They’re young, new. They’re high-spirited, cheerful. What a change from the self-pitying moaners, crooning their lovelorn tunes from the tortured shallows of lukewarm hearts.

The Beatles are whacky. They wear their hair like a mop – but it’s WASHED, it’s super clean. So is their fresh young act. They don’t have to rely on off-colour jokes about homos for their fun …

Youngsters like the Beatles are doing a good turn for show business – and the rest of us – with their new sounds, new looks.

Good luck Beatles!

On perpetual guard against the new and unseemly, the Daily Telegraph condemned the delirium. ‘This hysteria presumably fills heads and hearts otherwise empty,’ argued the author of an anonymous editorial. ‘Is there not something a bit frightening in whole masses of young people, all apparently so suggestible, so volatile and rudderless? What material here for a maniac’s shaping! Hitler would have disapproved, but he could have seen what in other circumstances might be made of it.’

On their return to Leicester a year later, in October 1964, the Beatles attempted to execute their usual trick, rushing offstage and into their car while the National Anthem was playing. But in that brief period, the mores of society had changed: this time, a group of sixty or seventy fans failed to stand to attention, preferring to run out of the theatre and swarm around the Beatles in their car, hammering on the roof and windows. Discombobulated, the driver lost his nerve and careered into another car, but still the fans hammered away, forcing the Beatles to wait for the police to come and free them.

1 While writing this book, I have had nights when I have been kept awake as this or that Beatles song played over and over again in my brain. When it has been some particularly repetitive song – ‘Yellow Submarine’, say, or ‘All Together Now’ – I found that singing an opposing ‘God Save the Queen’ in some other part of my head proved the only way to drown it out. The trouble with this method, though, is that you are left with a song even more annoying than those it has replaced.

36

The sudden arrival of the Beatles came as a shock to many in the old guard of showbusiness.

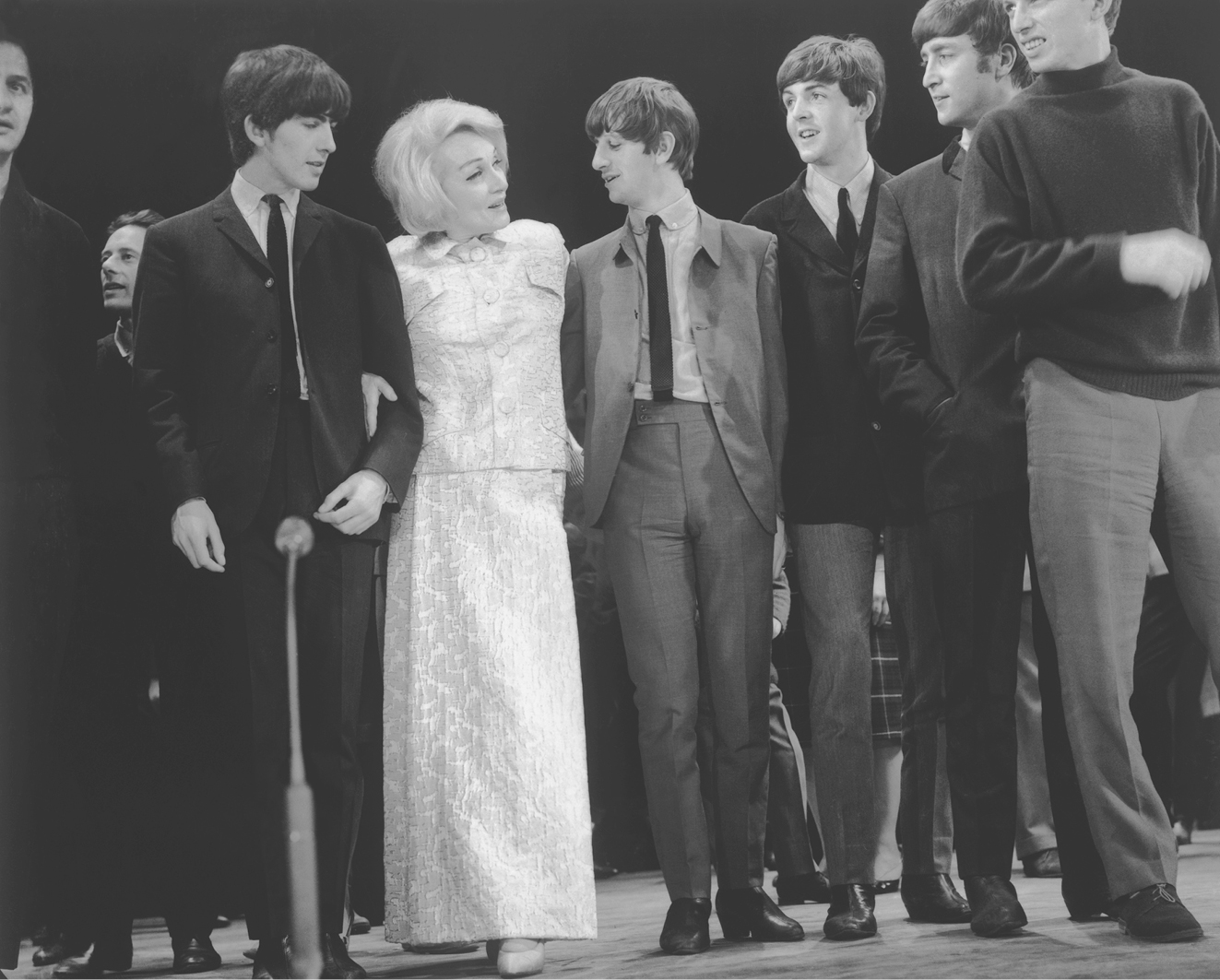

Marlene Dietrich, star of The Blue Angel (1930) and Blonde Venus (1932), was sixty-one years old when she agreed to appear in the 1963 Royal Variety Performance. Her international stature seemed to guarantee her the role of star of the evening.

In July 1963 the impresario Bernard Delfont was asked by his sixteen-year-old daughter Susan to book the Beatles for the show. Delfont was nonplussed: ‘I had never heard of them … when I asked what they did, she said they were somehow – well, you know – different.’

Soon afterwards, he heard that someone in his organisation had booked them for a Sunday performance at the Princess Theatre, Torquay. He immediately phoned the theatre manager.

‘How’s business?’ I asked the manager.

‘We’ve sold out,’ he said. ‘There are fans sleeping on the street, waiting for returns.’

That was good enough for me. I made the booking.

By November, the Beatles’ fame had eclipsed Dietrich’s. As the big day drew closer, Delfont noticed how much this upset Dietrich, who felt that all the kudos should be hers. ‘I anticipated a clash of temperament, but I should have known that Miss Dietrich would not stoop to a vulgar brawl,’ he recalled. ‘Instead, she fought back with all the subtle ruthlessness of Lady Macbeth.’

During rehearsals, Delfont’s sister Rita noticed Dietrich behaving ‘petulantly and selfishly’, hogging more than her fair share of the time available. When she had finished, all the photographers swept down to the front of the stalls. ‘Not now, darling!’ she ordered. ‘Come back in an hour when I’ve got my make-up on!’ It had simply not occurred to her that they were there for the Beatles.

The cameras flashed away as the Beatles rehearsed for their allotted period. ‘By the time Marlene returned, now resplendent in a sequined gown and wearing full make-up, there wasn’t a photographer in sight,’ recalled Rita Delfont.

The photographers returned for photocalls just before the show. Once again, the Beatles were the centre of attention, but each time they struck a new pose Dietrich would miraculously appear, elbowing her way into the frame. ‘The boys, who were still a little unsure of themselves, accepted the intrusion as a compliment. Not so the production team, who recognised scene-stealing when they saw it.’

George Freston/Stringer

Nevertheless, she made quite an impression on Ringo: ‘I remember staring at her legs, which were great, as she slouched against a chair. I’m a leg-man. “Look at those pins!”’

Dietrich herself finally warmed to the group. ‘They are so SEXY!’ she remarked to Brian Epstein after the curtain went down. ‘It was a joy to be with them. I adore these Beatles. They have the girls so frantic for them. They must have quite a time!’

Four years later, the Beatles repaid the compliment by placing Marlene Dietrich among the chosen few on the cover of Sgt. Pepper.

37

In the basement of the Ashers’ house in Wimpole Street was a little room where Margaret Asher would teach her pupils how to play the oboe. It contained a sofa, an upright piano and a music stand. When Margaret wasn’t in need of the room she let Paul use it to write his pop songs.

One day in mid-October 1963 John dropped by. The two of them went down to the little room in the basement and sat together on Mrs Asher’s piano stool. Brian Epstein had told them that their next, most important task was to compose a song to crack the elusive American market. Up to now, their hit singles in Britain – ‘From Me to You’, ‘She Loves You’, ‘Please Please Me’ – had all flopped over there.

Doodling about, they came up with the line ‘Oh, you-ou-ou got that something’. Paul hit a chord to accompany it. ‘That’s it!’ said John. ‘Do that again!’

After an hour or so, Paul went upstairs and put his head around the door of Peter Asher’s bedroom. ‘Do you want to come and hear something we’ve just written?’ he asked. Peter accompanied him back downstairs, and together Paul and John played him their new song, ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’.

‘What do you think?’ asked Paul.

‘Oh, my God! Can you play that again?’ said Peter. As he listened to it for a second time, he thought: ‘Am I losing my mind, or is this the greatest song I ever heard in my life?’

A day or two later, John and Paul took ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ along to the Abbey Road studios. They were speedy workers: in the same session they recorded ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’, its B-side, ‘This Boy’, their first Christmas message for their fan club, and half of ‘You Really Got a Hold on Me’. As if this were not enough, Paul left halfway through to go out to lunch with a girl who had won first prize in a ‘Why I Like the Beatles’ essay competition.

These were busy days. Over the next three weeks they packed in an appearance on Thank Your Lucky Stars, a tour of Scandinavia, the Royal Command Performance (‘rattle yer jewellery’), concerts in Cheltenham, Sheffield, Slough, Leeds and Northampton, and a trip to Dublin.

On 9 November they were driven in their Austin Princess to East Ham, where the crowds outside the Granada cinema were so wild that even the Beatles’ food had its own police escort.

Before they went onstage, George Martin put his head round the door and called for silence.

‘Listen, everybody, I’ve got something important to tell you all. I have just heard the news from EMI that the advance sales of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” have topped a million.’

Everyone cheered. ‘Yeah, great,’ said John, never slow to spot the cloud blocking a silver lining. ‘But that means it’ll only be at number 1 for about a week.’

‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ was released in Britain on 29 November 1963, little more than six weeks after John and Paul had composed it in an hour in Margaret Asher’s basement room. Two weeks later it reached number 1, knocking ‘She Loves You’ down to number 2. Contrary to John’s prediction, it was to remain at number 1 for another four weeks, and was in the charts until the end of April, by which time their follow-up single, ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’, had already topped the charts for three weeks.1

‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ was not released in America for another month, and then only after a notably random chain of events. A Washington disc jockey had been given a British copy by an air hostess, and played it over and over again on his show, prompting top-forty stations in Chicago and St Louis to follow suit. At this point, Capitol Records recognised its potential, and released it as a single on Boxing Day 1963. Within a week it had reached number 43 in the US charts; it seemed likely to climb higher.

1 ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’ surrendered its number 1 slot to another Lennon/McCartney composition, ‘World Without Love’, sung by Peter Asher and his friend Gordon Waller, jointly known as Peter and Gordon.

38

At three in the morning on 17 January 1964, the Beatles were in their palatial suite at the George V Hotel in Paris, having just played the first of a series of concerts at the Olympia Theatre. As they sat around in their pyjamas and dressing gowns, Brian Epstein came in, clutching a telegram.

‘Boys,’ he said, ‘you’re number 1 in America!’ For once, even John was thrilled. Their road manager, Mal Evans, witnessed their elation. To him they were ‘just a bunch of kids, jumping up and down with sheer delight’.

Lefebvre André/Getty Images

Ringo was cock-a-hoop: ‘We couldn’t believe it. We all started acting like people from Texas, hollering and shouting Ya-hoo.’ Paul climbed onto Mal’s shoulders and demanded a piggyback ride. There to cover their tour, the photographer Harry Benson suggested they stage a celebratory pillow-fight. ‘That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard,’ said John. A second later he picked up a pillow and whacked Paul on the back of the head, and then all four of them leapt onto the vast Empire bed and started walloping one another with pillows. In their pyjamas and dressing gowns, they continued their merry japes, picking Ringo up and – ‘One, two, three, four!’ – throwing him into the air. Would they ever again be so deliriously happy?

39

It had all happened so fast. Exactly a year before, on 17 January 1963, they had been playing the Cavern and the Majestic Ballroom, Birkenhead. A year before that, on 1 January 1962, they had been turned down by Dick Rowe of Decca Records, on the grounds that ‘groups of guitars are on their way out’.

And now they had cracked America. In the first three days of its US release, ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ sold a quarter of a million copies. It went on to sell five million.

The poet Allen Ginsberg was in the Dom, a ‘hip hangout’ in New York’s East Village, when he first heard the song: ‘I heard that high, yodelling alto sound of the OOOH that went right through my skull, and I realised it was going to go through the skull of Western civilisation.’ To the amazement of his fellow intellectuals, the portly Ginsberg got up and danced around.

When Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys heard it, ‘I flipped. It was like a shock went through my system.’ The current Beach Boys single, ‘Be True to Your School’, had the chorus:

Be true to your school now

Just like you would to your girl or guy

Be true to your school now

And let your colors fly.

In that instant, Wilson realised that the Beatles had rendered him antique. He was two days younger than Paul, but now felt like an old-timer: ‘I immediately knew that everything had changed.’

For the past six months the Beach Boys had been the most popular group in America. But from now on they would be obliged to live in the shadow of the Beatles. To make matters worse, the Beatles were signed to Capitol, the same label as the Beach Boys. The very same executives who had been giving the Beach Boys all their attention now couldn’t stop talking about the Fab Four. ‘The Beach Boys had been it for two years, but now people thought the Beatles were the future. And loyalties ran thin at Capitol,’ recalled their promoter, Fred Vail.

The following April they recorded ‘Don’t Back Down’. Unlike their other songs, it had an air of doom about it: ‘The girls dig the way the guys get all wiped out … When a twenty-footer sneaks up like a ton of lead’. It was to be the Beach Boys’ very last surfing song.

In Freehold, New Jersey, a fourteen-year-old boy was sitting in the front seat of his mother’s car when the song came on the radio. He felt time stop, and his hair standing on end. ‘Some strange and voodoolike effect’ took hold of him, ‘the radio burning brighter before my eyes as it strained to contain the sound’. They reached home, but he didn’t go in. Instead, he ran straight to the bowling alley on Main Street, rushed to the phone booth and called his girlfriend Jan.

‘Have you heard the Beatles?’ he asked.

‘Yeah, they’re cool,’ she replied. He then rushed to Newbury’s, a store with a minimal record section. ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ wasn’t in stock, so instead he bought a single called ‘My Bonnie’, apparently by ‘The Beatles with Tony Sheridan and Guests’. ‘It was a rip-off. The Beatles backing some singer I’d never heard of … I bought it. And listened to it. It wasn’t great but it was as close as I could get.’

He instantly set his heart on a guitar displayed in the window of the West Auto store on Main Street. When the summer came, his Aunt Dora paid him to paint her house, and he bought the guitar with the money he earned: ‘That summer, time moved slowly.’ He lived for every release by the Beatles. ‘I searched the newsstands for every magazine with a photo I hadn’t seen and I dreamed … dreamed … dreamed … that it was me … I didn’t want to meet the Beatles. I wanted to be the Beatles.’

Over half a century on, Bruce Springsteen still believes that hearing ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ that day in his mother’s car changed the course of his life.

In Chicago, the ten-year-old Ruby Wax was standing in a record shop when the B-side of ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ came blasting out.

‘Over the speakers the Beatles were singing “Well, she was just seventeen”, and all of my organs lit up into red alert. This was the most exciting sound I had ever heard – it was a Big Moment. No one man since then has ever switched the “on” button like they did.’

Over the next few weeks, Ruby plastered her bedroom wall with Beatles posters, which she then ritually licked. She collected Beatles magazines, pens, records, sunglasses, clocks, socks and stickers. ‘I would turn up the sound of my Beatles records to eardrum-shattering levels and weep and moan and scream out my love.’ She would even call the telephone operator in Liverpool just to hear her say ‘Hello’ in a Scouse accent. ‘Then I’d become so overwhelmed I’d have to hang up.’

Serving a ten-year sentence in McNeil Island Corrections Center, Washington State, the petty criminal Charlie Manson kept hearing ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ playing on the radios circulating among the inmates.

According to his biographer, Manson was impressed by the music, but far more impressed by the adulation the Beatles were receiving: ‘Charlie always yearned for attention; now he decided that fame was what he really wanted. If these four Beatles could have it, why couldn’t he? … Charlie started telling anyone willing to listen and also those who weren’t that he was going to be bigger than the Beatles.’

From that point on, Manson spent his time in McNeil hunched over a guitar. Whenever his mother Kathleen came visiting he would tell her, with an almost manic insistence, that one day soon he too would be famous.

40

In January 1964 the Ronettes came to London to headline their first British tour, supported by a local group, the Rolling Stones.

On their first night a party was thrown for them by the Radio Luxembourg disc jockey Tony Hall at his home in Green Street, Mayfair, just down the road from where George and Ringo were living.

John, George and Ringo were already there when the Ronettes came in. The Ronettes were aware of the fame of the Beatles – since their arrival they had heard of little else – but had still not heard their music. For their part, the three Beatles were mustard-keen on the Ronettes, with their lusty, yearning voices and shapely bodies.