The Beast and the Bethany

“But—”

“No buts,” said the beast. “You need your potion by Saturday, and I want to eat a child before then. Bring one to me, and you will continue to live a long and happy life.”

“And if I don’t?”

“Then you shall die, Ebenezer. Without the potion, your body will give in to your old age, and you will be nothing more than a pile of bones. I would be most upset about it.”

Ebenezer wondered whether he cared that much about children after all. He didn’t really want to feed one to the beast, but he also didn’t think that any child was worth more than his own life.

“Are you sure there’s nothing else I can bring you to eat instead?” asked Ebenezer.

“A child is the only thing I want,” answered the beast.

“Well, then,” said Ebenezer. “Let me think about it.”

The thinking didn’t take very long.

“I’ve thought about it, and I think it’s a wonderful idea. There’s no reason why you shouldn’t have a child to eat,” said Ebenezer. “Would you mind vomiting out a large brown bag for me? Ideally the same size as the one you gave me when I went hunting in the South Pole.”

The beast hummed and wiggled and vomited out a strong, Emperor−penguin−sized bag. Ebenezer ran downstairs and jumped into the car with it.

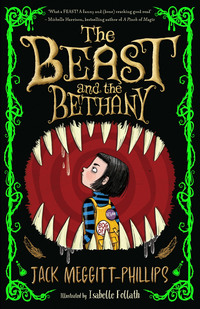

He drove straight to the zoo, beeping and weaving his way through the traffic with all the patience of a cranky toddler. He made it to the ticket office with just ten minutes to spare before closing time.

“Adult or child?” croaked the old lady at the ticket office. She was small and scaly, and looked like she might be better suited to the lizard enclosure.

“I want a child, please,” said Ebenezer, breathlessly.

The lizard lady peered closely at Ebenezer and raised her thin eyebrows in a questioning manner.

“I mean, an adult ticket. Because I am an adult,” said Ebenezer quickly, as he laid down some coins. “It may surprise you to learn that I’m actually 511 years—”

The lizard lady didn’t care, she snatched the money and let Ebenezer and his bag through the barrier.

But Ebenezer didn’t focus on this. He was too busy congratulating himself.

He knew there would be children at the zoo, because he had spotted a few during the time he had kidnapped a peacock to feed to the beast, but he had no idea there would be so many. The place was an all–you–can–eat buffet of snot and nits and tiny fingernails.

Ebenezer approached a frowny girl who was stood near the elephant sanctuary. He opened his large brown bag and invited her to jump inside.

“Come on then,” said Ebenezer, when the girl refused to play ball. “I haven’t got all day.”

“DADDY! DADDY! IT’S A STRAAANGEEER!” shouted the girl.

Within moments a man (similarly frowny), marched up to Ebenezer. He shouted twelve rude words and made two nasty threats, before he led his daughter away.

Ebenezer shrugged, and then tried his bag trick on another child.

And then another.

And then another two more.

Every time he found a child, there was a blasted parent lurking somewhere nearby. Pretty much all of them had unpleasant things to say when they saw Ebenezer try to stuff their children into his bag.

Soon, the complaints mounted up, and Ebenezer was dragged back to his car by a security guard the lizard lady had brought with her. He finally accepted the fact that he would have to think of something else, when he received a lifetime ban notice from the head zookeeper.

The something else that Ebenezer thought about was a sweet shop. Whenever Ebenezer went to his local sweet shop, there were always greedy children with sticky fingers and dirty mouths swarming around the place. And some of these children were there without their parents. The only adult who could get in Ebenezer’s way was the sweet shop’s eccentric and experimental owner, Miss Muddle – annoyingly, all the children seemed fascinated by her.

In order to get around this problem, Ebenezer decided to set up his own sweet stall. He got the beast to vomit out a banner, which read ‘Mr Ebenezer Tweezer’s Candy Palace’, and he set up a table on the street, filled with all manner of sweet goodies that he sprinkled with sleeping powder so that he could easily transport the children to the beast’s attic.

After a short while, Ebenezer’s first customer arrived. He was a twelve−year−old named Eduardo Barnacle, who was in possession of the world’s third largest set of nostrils. They were wide enough to each hold a small orange.

“Well, well, well – what do we have here?” asked Eduardo. He bent over Ebenezer’s table and took a deep sniff of each of the sweet things on offer.

“We have liquorice allsorts, Catherine wheels, strawberry fancies, sherbet pips, banana bonbons – the whole party.”

Eduardo sniffed again. The rims of his nostrils swelled and shrank greedily upon his nose.

“This is the strongest selection I’ve seen in a while. Congratulations, Mr Tweezer,” said Eduardo. He was oddly confident in his ability to speak to grown−ups as if he were one. “How much will it cost if I purchase a sample of each one?”

“Two hundred and fifty−three pounds, and sixty− two pence,” answered Ebenezer, a little too quickly. He wasn’t used to dealing with money, because he normally relied on the beast, so he didn’t really know how much things cost.

Eduardo shook his nostrils (and the rest of his head) sadly from side to side, and walked away from Mr Ebenezer Tweezer’s Candy Palace. Ebenezer chased after him.

“Sorry, sorry – I got that all wrong. I meant to say eighty−five pounds and ninety−four pence. What a bargain!” he said.

Still, Eduardo continued to walk away, so Ebenezer offered the sweets to him for free. Then he offered to pay Eduardo to eat them.

“How much will you give me?” asked Eduardo.

“Seven hundred and forty−six pounds?” suggested Ebenezer.

“Well, clearly your sweets can’t be very good then. Good day, Mr Tweezer.”

Eduardo marched back home, with his nostrils held high in the air, and refused to return. Ebenezer resumed his position behind the table, helped himself to a Catherine wheel, and pondered whether he should remain outside. He promptly fell asleep, face first into a strawberry fancy, before he remembered the sleeping powder.

Seven hours later, in time with the sunrise, Ebenezer sat up, somewhat chilly from his night on the street. He decided that he had had quite enough of this sweet shop business.

“There has to be an easier way!” he said, crossly to himself.

For the first time in his life, Ebenezer was sad that he didn’t have a family of his own. It would have saved so much time and energy if he could have just fed one of his children to the beast.

He went back to the house, changed clothes, ate some truffles on toast and climbed into his car. He drove straight to the bird shop, where the bird−keeper was busy feeding some parakeets their breakfast.

“Good morning,” said Ebenezer.

“Ah, Mr Tweezer!” said the bird−keeper. “So happy to see you. I had an awful dream about Patrick last night. I dreamed he was screaming for my help. Ain’t anything wrong with him is there?”

“He was a bit uncomfortable last night,” said Ebenezer. “But I think it was just indigestion. That’s all over now, thankfully. He hasn’t screamed at all today.”

“Oh good, that’s such a relief. I was so worried,” said the bird−keeper. “So what can I do for you? Are you looking to buy a friend for the parrot?”

“In a way, yes. I’m looking for someone who will join Patrick in his new home.”

“Well, I got loads of them here. I had some society finches come in last week, would you like to see them?”

“I actually have something in mind already,” said Ebenezer. “It’s a bit of an unusual request. I was wondering whether you might have any children for sale?”

“Did you say ‘canary’?”

“No, I said ‘children’. I’m not fussy about size, and I don’t really mind whether it’s a boy or a girl.”

“Right . . .” The bird−keeper took a quick look around his shop. “Sorry, mate, but I don’t think we got any of those. Got a lovely little cockatoo, at a very reasonable price, if that works? Or a half−moon owl?”

“No, thank you, I only want a child. How about the one who came in here yesterday? I believe her name was ‘Bogoff’?”

“Never seen her before last night, I’m afraid. And hope I never see her again. The backpack turned out to be broken in several places, and that biscuit was far too soggy,” said the bird−keeper, shaking his head.

“I see,” said Ebenezer. “I suppose I’ll have to try elsewhere.”

“Wait a mo,” said the bird−keeper, as Ebenezer started to leave. “Why are you wanting a child?”

“It’s just something I need. My life depends on it,” said Ebenezer.

“Ah, how sweet. I remember my wife and I felt the same before we had little Tommy. A child is a wonderful thing,” said the bird−keeper.

“This little Tommy, would you be willing to part with him? I’ll pay whatever price you ask,” said Ebenezer.

“He’s not for sale!” said the bird−keeper. “My wife would kill me.”

Well, it was worth a shot, thought Ebenezer. He started making his way towards the door again. His shoulders were slumped and he was feeling very sorry for himself.

“Oi!” said the bird−keeper. “You can’t give up just like that.”

“I don’t really know what else I can do,” said Ebenezer. “There are too many parents at the zoo.”

“Eh?” The bird−keeper frowned. “Haven’t you tried the orphanage?”

“The orphawhat?” asked Ebenezer. It was a word he had never heard before.

“Yeah, you should try the orphanage three streets down. Miss Fizzlewick runs it, and she’s got dozens of little ones who need a home.”

“But what about the parents?” asked Ebenezer.

“That’s the whole point, these children ain’t got no parents. The parents are dead, or lost, or just not around.”

Ebenezer was surprised. He had no idea that people had such sad lives.

“Do you think I’d be able to get one by Saturday?” he asked the bird−keeper.

“Don’t see why not.”

“Marvellous, absolutely marvellous!” Ebenezer opened his wallet and threw a wad−load of cash at the bird−keeper to thank him for the very excellent advice. “You’re a life–saver!”

Ebenezer ran out of the shop and jumped back into his car. All he had to do now was find the orphanage.

The Children’s Menu

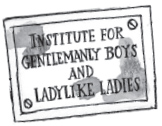

The orphanage was a squat, ugly building with cracked windows and peeling paintwork. There was a rusty sign at the top of the gates which read ‘INSTITUTE FOR GENTLEMANLY BOYS AND LADYLIKE LADIES’.

Ebenezer shuddered as he looked at the place, and he was shocked that anyone was expected to live there. He thought it was no wonder that the orphanage had so many children going spare. It was not the sort of place that attracted customers.

As Ebenezer got out of his car, he was met by Miss Fizzlewick, the director ofthe orphanage. She was a tall, thin woman, with stern eyebrows and a wild tangle of grey curls at the top of her head.

“Good morning,” said Ebenezer.

Miss Fizzlewick flinched.“The correct greeting when meeting a lady for the first time is ‘how do you do?’ Now, are you bringing children, or looking to take one away?”

“Take one away, please,” answered Ebenezer.

The twitchy beginnings of a smile formed at the corner of Miss Fizzlewick’s lips. It had been several weeks since she had been able to get rid of a child.

“You should have said sooner, come on through!” she said.

Miss Fizzlewick decided to show Ebenezer that she was now in a ‘friendly’ mood by smiling at him. Her teeth were yellow and cracked, and her gums were an unhealthy shade of dark red.

“As you can see, I keep a firm watch over this place,” she said, as she led him into the building. “I believe it’s impossible to raise well−behaved boys and good little girls unless everything is kept clean and tidy.”

Ebenezer laughed because he thought this was a joke. The orphanage was dusty, dirty and littered with cobwebs.

“Is there something you find funny?” she asked.

“Um, no. I was just thinking about something I saw on TV the other day,” answered Ebenezer.

Miss Fizzlewick flinched again. She didn’t approve of modern technology. “Watching television is most ungentlemanly,” she said.

Miss Fizzlewick led Ebenezer into her office, which was guarded with a sign that read ‘No Children Unless Absolutely Necessary!’ The room was significantly less dirty, dusty and cobwebby than the rest of the orphanage, and it was filled with all sorts of fabulous and beautiful things that weren’t on display anywhere else.

Miss Fizzlewick took a seat at her desk. It was hidden underneath a mountain of paper and teacups.

“I’m very organised,” she said with a serious face. Ebenezer didn’t laugh this time. “Would you like anything to drink?”

Ebenezer was thirsty, but he didn’t believe that anyone who was so unorganised would be able to make a good cup of tea.

“No, I’m fine thanks,” answered Ebenezer.

“Good, good. Now let me just fill out the paperwork,” said Miss Fizzlewick. She fumbled around her desk before finally finding a blank form. “What’s your name?”

“Mr Ebenezer Tweezer.”

“Do you live in the area?”

“Yes, a five−minute drive away. Three if I went fast.”

“Excellent. How old are you?”

“511, but on Saturday I’ll be 512.”

Miss Fizzlewick looked up from the form, baffled by Ebenezer. She brushed some grey curls away from her ears and asked Ebenezer to repeat his answer.

“Thirty,” said Ebenezer. “Yep, that’s what I meant to say. I’m thirty years old. Gosh, I’m so young.”

“Well, if you don’t mind me saying, I think you look even younger than that, Mr Tweezer. You don’t look a day older than twenty,” said Miss Fizzlewick, with a toady smile.

Ebenezer always felt a rush of pride when he heard this, in spite of the fact that he had been paid the compliment several times.

“Anyway, let’s get on with the important business,” continued Miss Fizzlewick. “What type of child are you looking for?”

“I’m not fussy,” said Ebenezer. “Just give me the cheapest one you have.”

“The cheapest?”

“Yes, please. But if the cheapest is total rubbish, then I’m willing to pay more.”

“Mr Tweezer, do you know how an orphanage works?” asked Miss Fizzlewick with a suspicious frown. “You do know that you don’t have to buy the children? We give them to you for free!”

Ebenezer thought this was a very odd way to run a business. Perhaps if Miss Fizzlewick charged for the children, then she might have enough money to afford a prettier building. However, he wasn’t going to complain.

“Marvellous,” said Ebenezer. “So what happens next?”

“Well, now you meet the children. I’ll line some of them outside my office so that you can interview them, one at a time. How old would you like the child to be?”

“I don’t mind,” said Ebenezer.

“How about shoe size? A lot of people are favouring children with a size four shoe these days.”

“I don’t mind,” said Ebenezer.

“Mr Tweezer, you must have some idea of what you’re looking for. You must know whether you want a boy or a girl?”

“I really don’t mind,” said Ebenezer impatiently. All he could think about was getting the potion as quickly as possible. “Honestly, any child will do.”

Miss Fizzlewick wished that Ebenezer had at least one opinion on the matter. It would have made the business of getting rid of a child a lot easier.

“Right then,” said Miss Fizzlewick. “I guess that you’re going to have to meet all of the children. I hope you don’t have any plans for the rest of the morning.”

Miss Fizzlewick went to fetch the children, all twenty– seven of them. She lined them outside her office, whilst Ebenezer tapped his fingers impatiently on the desk.

“Here’s the first one. Her name’s Amy Clue, and she’s just joined us. Come on in, Amy, and for goodness’ sake, don’t be shy. It’s very annoying,” said Miss Fizzlewick.

Amy was a shy little girl, and her shyness wasn’t helped by adults telling her not to be shy. She was no older than three and not much taller than a tennis racket. She poked her head nervously around the door and looked at Ebenezer.

“How do you do?” said Ebenezer. He offered Amy a hand to shake.

After much nagging, Miss Fizzlewick dragged Amy into the room. She hugged a battered pink teddy bear in one hand, and waved shyly to Ebenezer with the other.

Amy was too small to reach the chair, so Miss Fizzlewick lifted her up and let her stand on the desk. Amy smiled at Ebenezer, whilst Miss Fizzlewick wiped her hand on her trousers to get rid of any germs she might have picked up.

“Ewoh!” said Amy.

“I beg your pardon?” said Ebenezer.

“Ewoh!” said Amy, waving again. “Ewoh! Ewoh! Ewoh!”

Ebenezer was unsure about how he was meant to respond.

“I’m afraid she’s rather behind on her elocution lessons,” said Miss Fizzlewick, sighing impatiently. “She’s trying to say ‘hello’, AREN’T YOU, AMY, MY DEAR?”

“Oh, I see,” said Ebenezer, wincing at the volume. “Ewoh to you too, Amy. It’s a pleasure to meet you. Well, well, well, what do you think about the weather today? Hasn’t it been miserable?”

“Eh?” asked Amy.

Miss Fizzlewick explained that Amy was still learning to speak, and that she didn’t know what words like ‘weather’ and ‘miserable’ meant. Miss Fizzlewick told Ebenezer that he should stick to simple, toddler−friendly topics.

“Ah. Quite right.” said Ebenezer.

He didn’t spend much time speaking with toddlers and he found it tricky to think of what to say, but then he hit upon the brilliant idea of talking to Amy about her teddy bear.

“What’s his name then?” he asked, pointing at the teddy.

“’S not a boy!” Amy laughed so hard, she looked like she might fall off the table. “’S a girl, an’ is named Miss Lillipie.”

“Miss Lillipie, eh? What a fun name. Good morning, Miss Lillipie, how do you do?” asked Ebenezer, offering another handshake, but this time to the teddy bear.

Amy found this funny. The desk wobbled, as she let out a roar of laughter.

“E’s funny!” said Amy, pointing at Ebenezer. “I like him.”

Ebenezer liked Amy as well. She wasn’t going to win any conversation prizes, and she needed to work on her annoying laugh, but aside from that she was very cute.

“Mr Tweezer, what do you think? Would you like to take Amy home with you today?” asked Miss Fizzlewick, as she rubbed her bony hands together.

“Yes,” said Ebenezer. “Yes, I would.”

Amy squealed with delight, and started dancing round the table with Miss Lillipie. Miss Fizzlewick shrieked with joy, and her twitchy smile broke out into a triumphant, yellow−toothed grin.

Ebenezer was happy as well, and he thought it would be good fun to have Amy around the house – it would certainly be more enjoyable talking to her than the beast.

Ebenezer gasped, as he thought about the beast. For a moment, he had forgotten why he had come to the orphanage in the first place. He wasn’t here to find a child he liked; he was here to choose a meal for his master.

“Wait, no!” blurted Ebenezer. “No, no, no – I can’t take Amy! She’s not what I want!”

Amy stopped dancing around the table with Miss Lillipie. She stopped squealing with delight, and started crying instead. She lifted her arms for someone to cuddle.

Miss Fizzlewick huffed impatiently, dumped Amy on the floor, and ordered her to stop snivelling and blubbing all over the place. Ebenezer looked at his watch, wondering how long it was going to take. He was already a bit bored with spending time in the orphanage.

“Perhaps the next one will be more your cup of tea,” said Miss Fizzlewick, as Amy left the room.

The next one was a tall, polite boy named Geoffrey. His parents had drowned in a lake two years previously, and he had been trying to honour their memory by being as good a boy as possible ever since.

As he came into the office, he lingered in front of a fabulous, glittering snow globe, featuring a ballerina dancing in the street.

“Miss Fizzlewick, is that my mother’s snow globe?” he asked.

“Never mind that, it’s perfectly safe here. Besides, it’s most ungentlemanly to ask a lady about her private property.”

“Sorry, Miss Fizzlewick – it won’t happen again.”

Ebenezer could already tell that Geoffrey was far too nice to feed to the beast.

“Next!” shouted Ebenezer, whilst Geoffrey was in the middle of introducing himself. “I don’t want this one either.”

Geoffrey was dragged outside by Miss Fizzlewick. Ebenezer got through another ten children within the space of twenty minutes. All the ones he saw were far too pleasant. He had no idea that it would be so tricky to find a bad child.

“I thought you weren’t fussy,” snapped Miss Fizzlewick. “I thought you said that any child will do?”

“Yes, sorry for the delay,” said Ebenezer. “But I need to be absolutely sure I get the right one.”

Miss Fizzlewick was growing impatient with Ebenezer. There was a certain frostiness in her voice as she introduced the next child. “This one is called Harold Chicken. Hopefully he’ll be more your cup of tea.”

Ebenezer could tell almost immediately that Harold Chicken was not going to be his cup of tea. For one thing, he was too smartly dressed to be bad, and for another he was smiling with too much kindness.

Ebenezer was about to shout ‘Next!’ when he heard a scuffle taking place outside the office. Geoffrey was screaming ‘Help! Help!’ and a girl was shouting ‘Shut up, you little rat!’

Ebenezer leaped off his chair and joined Miss Fizzlewick to see what was happening. Geoffrey was pinned on the f loor by the small, bony girl from the bird shop. The girl was shoving worms up his nostrils, and she was shouting ‘Rat! Rat!’ at him.

“Stop that at once, Bethany!” screeched Miss Fizzlewick.

Bethany sulked as she removed her worms and fingers from Geoffrey’s nostrils. Miss Fizzlewick turned to Ebenezer.

“I’m sorry you had to see that, Mr Tweezer,” she said. “I should have left Bethany in her room.”

“No need to say sorry,” said Ebenezer, with a wide smile on his face. “After all, I should be saying thank you. I think you have just helped me find the child who I want to take home.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги