Under Pressure

* Rigid inflatable boats.

† All captains have to pass the Perisher course to command a submarine, and all seconds-in-command on nuclear submarines will have also passed the course.

3

The Bomber

I was greeted on the casing by the coxswain, CPO Freddy Maynard, a gruff northerner of Yorkshire descent. On initial impression he seemed fair, despite possessing the look of a man not to be crossed in any shape or form. The coxswain is the chief of the boat, the head NCO who looks after its company in terms of discipline; if you’re up before the captain because you got pissed in Helensburgh and started acting like a spoilt arsehole, it’s the coxswain who’ll be giving you the evil eye and enforcing any punishment according to Navy regulations. Chief of the boat, he’s the third most important person on board after the captain and the XO.

It was time to go on board and see what all the fuss was about. Even though I’d had three months of training, this was the first time I’d ever stepped aboard a nuclear submarine. I was shitting it. The main access hatch was a straight drop down a ladder of about 10 to 12 feet, starting off vertical, then halfway down kicking out towards 1 Deck, as the top deck of the submarine’s three decks was known. The first thing I noticed was the claggy heat as I reached the bottom and turned 180° to carry on down to 3 Deck, where my locker and bunk were located. There was a distinctly stale odour down here: the ghosts of farts long dead, mixed with heat, oil and the CO2 absorption-unit chemicals they used to recycle air back into oxygen. Add to that special cocktail the collective sweat of a crew of 143 men and bingo, you had the submarine smell. It was grim all right.

The second thing to strike me was what lay immediately above my head – and the need to duck. I cracked my forehead on the overhang of the steps down to 3 Deck, giving me a nice egg of a swelling above my left eyebrow. Although Resolution was the biggest submarine built by the Navy at that time, it was hellishly cramped in terms of living space, and moving around its tiny passageways required all manner of contortion. The raison d’être of the submarine is first and foremost machinery and functionality, with the bodily needs of men coming a distant second. I noticed valves, gauges, low ceilings, wires, switches and dials all round, and wondered how in hell I was going to cope learning the mechanics of all of this.

Two people couldn’t pass on a corridor without one moving aside. You could stand in the middle of the passageways on 1, 2 and 3 Deck with your outstretched hands and touch either side of the sub. It was impossibly tight. Then there were the protruding pipes to bang your head on, bulkheads to trip through, small hatches to navigate, valves and dials all over the place, plus vertical ladders between decks … there were risks everywhere. I had to pass through hatch after hatch and ladder after ladder before getting to my bunk at the bottom of the boat. The lack of space was giving me the fear. I couldn’t let on, but on first impressions I wasn’t sure life in a steel cigar-shaped tin can was going to work for me. It was all the equipment, for fuck’s sake. It was everywhere you looked, coupled with those passageways and ladders eating up all available living space. Plus, there were nuclear weapons and a nuclear reactor to worry about, never mind their impact on the space. I was already starting to regret my ballsy decision to become a submariner.

The walls started to close in as panic got a hold of me, so I ran to the toilets to take some deep breaths. Christ, we hadn’t even left the dock yet and I was getting into a state. I just needed to regroup a moment. Anyone who tells you they’re not nervous when they first step on board a submarine is talking nonsense; the machinery, claustrophobia and alien smells, it’s not good for the uninitiated.

Fortunately, the crew were mostly friendly and eager to help me settle in. I started to calm down after about five minutes as I messed about and put my kit in my locker along the passageway near my bunk space, although ‘locker’ is probably overdoing it. Was I really supposed to fit my kit for a two-month patrol in there? It was about half the size of one you’d find in a local swimming pool. There was a drawer back in my sleeping compartment where I could put my shoes and boots, but storage-wise that was it. I rolled out my Navy-issue green sleeping bag on my bunk and left my own pillow on top. The lack of privacy was plainly obvious. I was going to have to put my faith in the hands of my fellow crewmates and needed to be a good judge of character.

Submariners hanging out in 9 Berth, where I spent my time in the land of nod. My bunk was the top one in the middle rack of three, never the bottom. (Wood/Express/Getty Images)

My main fear was that I couldn’t do it, that it would all be too much. How would I cope? What dangers would lie ahead? How the hell was I going to remember everything – both my job and everyone else’s – while contending with this ever-present claustrophobia. I’d only experienced being cramped in an escape hatch at the SETT at HMS Dolphin, but ten minutes in the submarine and I was already having a crisis of confidence. How would I manage being underwater without daylight for anything up to 80 or 90 days? And nuclear weapons? What if we had to use them?

It was still the height of the Cold War, with Gorbachev only recently having come to power, and the Soviets were hard at it. The Navy’s hunter-killer nuclear subs tracked their aggressive submarines across the North Atlantic, in the waters between Greenland, Iceland, Scotland and the Arctic Ocean, while our diesel-electric O-boats penetrated Soviet waters via the Barents Sea. It was like time had stood still for the last 15 years, each side trying to gain the upper hand.

The Americans, too, in their ‘Los Angeles’ fast attack submarines, were playing cat-and-mouse games in the Pacific, with Reagan well into his second term as president and hawkish as ever, despite the apparent friendly overtures from the Soviets now that the affable Gorbachev wielded power.

I wasn’t the only new starter; Philip, a bright, introverted lad from the Lake District whom I’d gone through training with at HMS Dolphin, was joining the boat at the same time. In addition, there were a couple of other junior rates,* all of us within the warfare team in the boat and collectively under the guidance of the coxswain.

As a submarine ship’s company is notably smaller than, say, that of a frigate or aircraft carrier, the coxswain is the de facto master-at-arms, a person to keep on the right side of. His main duties include being in charge of operating ship control while diving, surfacing and returning to and from periscope depth (PD); supervising the ratings who control the foreplanes and afterplanes, which regulate the depth and pitch of the boat; and overseeing new members of the crew. He would keep a steely eye on us throughout the forthcoming patrol.

The coxswain, like every other submariner on board, does more than one job. The leading steward, for example, will serve the captain his meals, then half an hour later will be on the foreplanes helping to bring the submarine to periscope depth. The beauty of this is that all qualified submariners can do their own jobs very well, but unlike other members of the armed forces they’re also proficient at everyone else’s. I might have been the nearest person to an emergency – be it fire, flood, hydraulic burst or ruptured air pipe – and I had to know how to deal with it and isolate the various systems involved in order to make the boat safe. This level of responsibility is unique within the services. Everyone here is in the same boat, and as JFK said, ‘We all breathe the same air’ – quite literally on a submarine, and for three months with no escape. You have to get along with each other.

In order to get to become a member of that rare club I had to undergo Part 3 training with a mentor at sea, and then an oral exam with the XO, the second-in-command, who himself had passed the Perisher course. Our XO had already captained a submarine, so was biding his time until his own bomber command came through. The coxswain and usually one of the chief MEMs (marine engineering mechanics), comprised the remaining members of the exam board. All the knowledge I’d picked up at submarine school seemed worthless, for while it might help with my own job, it was of no use in terms of the many skills required to make the boat function, nor did it mentally prepare me to keep on top of everything. Everyone I met on board said the same: ‘Forget all that shit, complete waste of time.’ This was big-boy stuff, so it was time to knuckle down.

Resolution was 425 feet long by 33 feet wide and pulled a draught (distance from waterline to keel) of an inch over 30 feet. Her displacement when surfaced was 7,700 tonnes, and while diving 8,500 tonnes. The speed of the boat was roughly 20 knots surfaced and 25 knots submerged. The tear-shaped hull of a submarine is designed to be more aerodynamic when it is surrounded by water on all sides, hence it is faster underwater. The optimum depth to which the submarine can dive is over 750 feet.

As for her armaments: six Mk 24 Tigerfish torpedoes with a maximum range of 39 kilometres, travelling at a speed of around 35–40 knots, and 16 Polaris A-3 ballistic missiles with two Chevaline warheads per missile, with a staggering nuclear yield of about 225 kilotonnes. To put that into perspective, ‘Little Boy’, the Hiroshima bomb, yielded around 13–18 kilotonnes, while ‘Fat Man’, the Nagasaki bomb, weighed in at 20–22 kilotonnes. A deeply sobering thought when I considered what I was sleeping next to.

In terms of propulsion, the boat was fitted with a pressurised water nuclear reactor (PWR1) capable of powering it for a number of years. However, patrols were limited in duration by the supplies and food for the crew. Furthermore, the power generated by the PWR1 also helped with the distillation of sea water. Pumped into the two distillation plants, sea water was recycled into potable water by separating the salt vapour produced when it was boiled. The two plants could quite easily reach an output of over 10,000 gallons a day after which, free from impurities, the water made its way to the fresh-water tanks. The water was subsequently used mainly for cooling electronic equipment such as sonar computers and navigational equipment, but was also essential for use with reactor services, batteries and domestic services such as cooking. If any was left after all this we may have got some laundry done and had a ‘shower’.

The nuclear reactor also created the electricity for the life-support systems on board, such as oxygen regeneration and the expulsion of unwanted gases like hydrogen, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, in addition to heating the air circulating round the boat and powering a number of other systems. The water deep under the world’s oceans is around 3°C, so heat needed to be applied to various parts of the boat to keep the temperature regulated. Though not back aft in the engineering spaces or the galley, I might add, where temperatures could easily reach 40°C.

The reactor compartment was lead-lined, sealed and constantly monitored by the >manoeuvring room engineers under the expert guidance of the nuclear chief of the watch, who in turn ultimately reported to the marine engineering officer (MEO), one of the most professionally qualified and important positions in the whole of the armed forces, period.

The submarine was split up into the different departments that made up the ship’s company. These were headed up by the senior officers – the XO, weapons engineering officer (WEO) and MEO – who in turn reported to God himself: the captain. The warfare team was headed up by the XO, and its main function was to take the boat to war: tracking and evading enemy craft, keeping the submarine safe by controlling all the other systems on board, while maintaining the boat in a state of readiness to launch its devastating nuclear weapons.

The warfare team used the sound room, where you’d find the elite sonar team hidden in the dark, headphones on, as they collated and evaluated contacts through the use of passive sonar. Contacts were either audible sounds picked up by the sonar team, or, if a long, long way off, visible sonar traces were detected on one of their many screens and sent through to the control room, where they were tracked. Sound waves in the sea are affected by many things, the two main ones being the temperature and density of sea water, coupled with the many background noises of marine life and merchant ships. The sonar operator’s job of accurately classifying contacts was a hellishly tricky one and required a great deal of experience.

Passive sonar is the non-active kind, meaning the sonar operator just listened and didn’t actively transmit. He was able to identify the source of the noise by listening to the sound of the propellers, or using invaluable intelligence from SSNs,† which recorded the signatures of Soviet ships and submarines. The sonar operators were able to instantly classify the vast majority of sounds, be they a merchant vessel, oil tanker, fishing vessel or Soviet submarine. As passive sonar doesn’t transmit sonically, its only major drawback is that it is extremely difficult to work out the range of a contact, as it’s not getting a ping back from the target. Silence was paramount to evade detection, so active sonar was only ever used in sea-training exercises.

The data from the sound room detailing the craft’s bearing and movement was then transferred to the control room, and from this information the tactical systems team (including myself) were able to work out firing solutions relating to the enemy’s course, speed and range, which the XO and the captain could use or modify, depending on their own calculations.

The warfare team also navigated the submarine while she was on the surface, controlled the submarine at periscope depth for satellite navigational fixes and positioned the submarine before firing torpedoes.

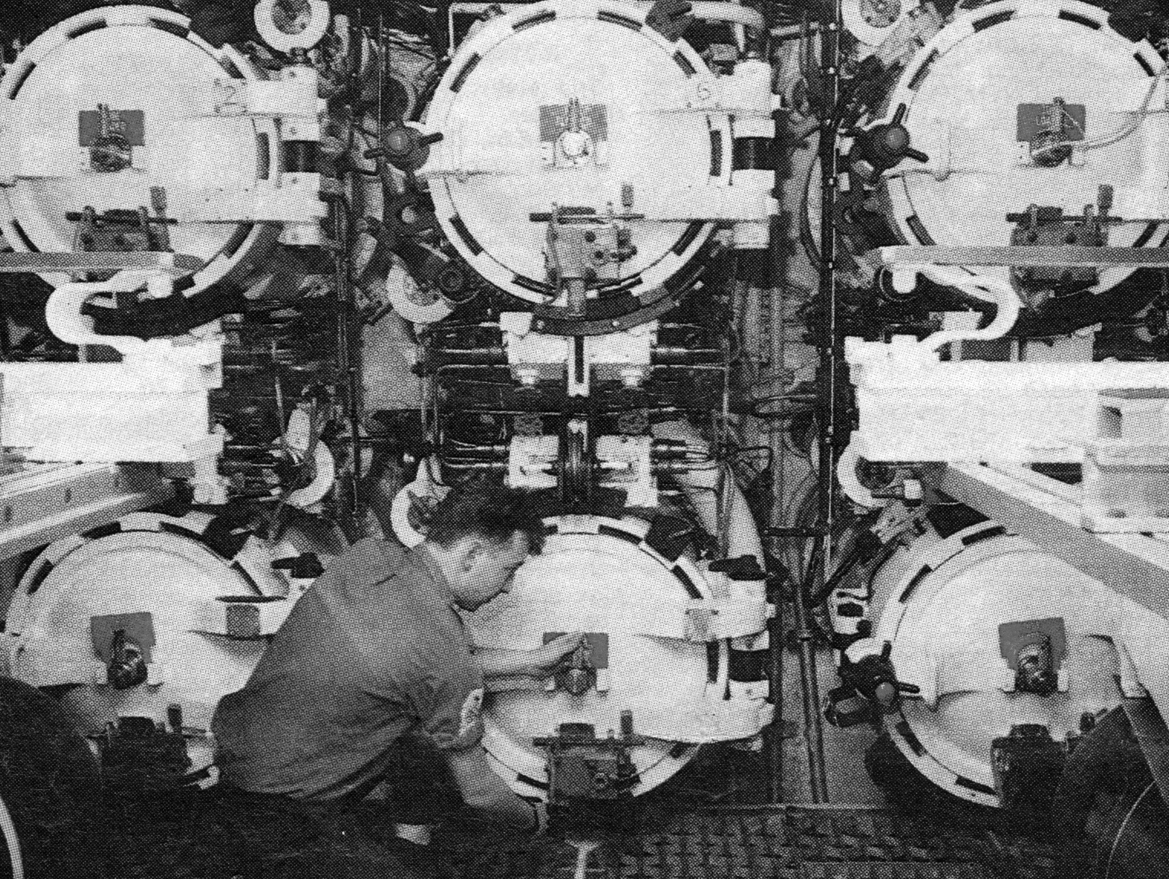

The weapons engineering department were responsible for maintaining and servicing the weapons on board, from nuclear missiles to the Tigerfish torpedoes, all of which were under the command of the WEO, who also pressed the trigger that would send the missile to its target. And yes, it was an actual trigger, coloured red just in case the WEO forgot what he was doing. In addition, they carried out electrical maintenance of the warfare team’s attack systems, sonar, electronic warfare, radio transmission and navigation, to keep them functioning at all times. This could either be routine maintenance or a complete strip and rebuild, which involved a riot of electrical leads spread out all over the floor awaiting reassembly. ‘Was it red first, then yellow?’ I’d often heard them say. I still don’t know the answer.

The Royal Navy newspaper Navy News visited the submarine to celebrate 21 years of the deterrent patrols in 1989. Here’s me posing for photos next to one of the torpedo tubes. (Navy News/Imperial War Museum)

When the boat was on patrol, there was a separate team of electrical engineers who kept vigil over the nuclear missiles in a cordoned-off area in the missile compartment. As well as loading the missiles onto the boat at the armaments depot, they packed the conventional torpedoes at the forward end of the boat and maintained them throughout patrol in the lower end of the fore ends, or ‘Bomb Shop’ as it was known. The team was supplemented by radio operators who looked after all the communications coming from the Command Centre at Northwood in north London, and who were based in the wireless room.

The engineers ensured that the nuclear weapons and torpedoes were safe through a system of round-the-clock, fail-safe checks. Their thoroughness and knowledge were vital, for at any time before a patrol began the men from the ministry in the form of the NWI‡ team could arrive for a snap visit and ask some pretty awkward questions, under the auspices of a weapons inspection. This could result in the WEO or any member of his team being relieved of their duties. This actually happened on Resolution, where a WEO was removed due to a perceived lack of knowledge on the day. At the time, we thought his had been a strange appointment, as the individual concerned had come from a Special Forces background and was thought to have been a serving member of the elite SBS. While that’s great in its own right, it hardly qualified him for a life under the sea in charge of nuclear weapons.

The marine engineering branch, led by the MEO, were tasked with looking after the boat’s propulsion, mechanical and life-support systems, and were split into two operating areas: aft (the back end of the submarine) and the control room, and everything forward of that. Aft of the missile compartment was their main focus, principally the manoeuvring room, for here were the controls that looked after the functioning of the reactor. Up to six people managed the detailed switches, pumps, hull valves and other bits of kit to make sure the reactor and its associated systems functioned correctly

The wrecking team manned the control room’s systems console, where they assisted in diving and surfacing the submarine, raising and lowering the periscopes, and monitoring oil pressures. They were also responsible for the diesel back-ups and maintaining the battery, should we ever have needed to use it in the event of the reactor being shut down. As well as maintaining their favourite bit of kit, the garbage and sewage systems, they also ran the laundry on 3 Deck, where clothes tended to come back as smelly as when they went in.

The final department was the supply branch, whose sole function was to ensure the boat had all the necessary food, drink, toilet rolls (essential, obviously. I never fancied using my hand to wipe my arse) and any other vital spares necessary for a ten-week patrol. This department was headed up by the supply officer and staffed by chefs, who did a superb job cooking three meals a day, plus snacks for months on end in the most testing of working conditions. Next time you’re in a restaurant, take a good look at the kitchens and all the chefs toiling in those cramped, hot and pressurised environments. Now, while they might be able to go for a fag break or some fresh air halfway through their shift, you can’t do that in a submarine. It’s torturously hot and stifling in the galley, with fire hazards aplenty … a total shit-show where miracles daily occur in keeping a crew fed and watered non-stop for three months, all of it happening in around 15 square feet.

The supply branch was completed by the stewards, who served the officers meals and drinks in the wardroom, and then did a shift on ship control, driving the boat with its changes of course and depth. And lastly there was the leading writer,§ who could usually be found holed up in the ship’s office doing all the coxswain’s admin; he also took his turn at flying the boat as well.

Then there was the doctor, who occupied a small sick-bay on 2 Deck, where he treated physically sick sailors. Don’t assume there were any mental health considerations, mind you. If someone rocked up and complained, ‘I’m not feeling that great today, Doc. Can we have a chat about it, please?’ the main gist of the doctor’s response would be, ‘Yes, of course, now fuck off.’ He also doubled up doing a turn on ship control, where he helped look after the pitch and depth of the boat while it dived and was at periscope depth. The occasional failure to carry out that part of his obligations resulted in him being on the end of some almighty bollockings from the captain.

That said, these always seemed to wash over him, for he was not easily irked. I guess doctors don’t get intimidated that easily. Although he was an officer with the rank of surgeon lieutenant, the doc I served all my patrols with preferred the company of the junior rates and drank heavily with us, always first in the queue for the pub on a night out and one of the last home, as well as being a heavy smoker. I’m not sure how he would have been judged by modern-day NHS standards, but he was great company – thoroughly entertaining, clever, level-headed and entirely unflappable. That said, I’m not sure I’d have wanted him taking my appendix out or resetting a broken bone.

The other major feature of the submarine particular to the nuclear deterrent was that it was made up of two crews, Port and Starboard (my crew). While one crew was out on patrol the other crew would be on the piss, on holiday or on training exercises. The main reason for this was maximising the amount of time any one of the four submarines could spend at sea. On these training exercises, we’d go to a simulated control room in Plymouth, where we’d practise both attacking and evasive manoeuvres in front of teaching staff who would judge our performance. It would be back-to-back, full-on attack-simulation training, with the warfare team under the leadership of the captain.

We liked these simulations. It made for a nice change to practise attacks on enemy ships or submarines, and they kept our hand in, for our main task on patrol was to evade and hide, not to engage or investigate like the SSN hunter-killers, or the diesel submarines that spent their patrols intelligence-gathering in Soviet waters and tracking enemy submarines. On the attack drills I usually found myself paired up with the captain as his periscope assistant. This consisted of helping the team effort by working out my own range of given target/targets using the angle of its bow and a 360° protractor slide-rule. The captain could then choose to ignore it, use it, or refer to it as a ballpark figure to help him with his own calculations. This full-on training lasted around a week, and to relieve the stresses of the day we partied hard in Plymouth. It led me back to some of my old ‘run ashore’ haunts on Union Street that I’d first encountered near the end of my basic training.

Aptly named, Boobs nightclub left little to the imagination; drink was consumed on an industrial scale, one-night stands were commonplace, with women and sailors in various states of undress while still in the club. Full-on debauchery ran amok, and I remember a particularly frantic half-hour of my own in the ladies’ loos. The night would usually end side-stepping vomit or fighting men, occasionally women, or both at the same time, always alcohol-induced. Once, on exiting Boobs en route to our favoured Chinese takeaway, I saw a sailor come hurtling through the window; landing with panache, he dusted himself down and strolled off into the night like a gracefully listing galleon.

Our other haunt was Diamond Lil’s, with Ronnie Potter. Ronnie played his Hammond organ while his wife sang mainly blue songs, as strippers did their thing on a raised stage, dragging inebriated sailors up for audience participation. All very bizarre, a kind of sleazy version of The Good Old Days, it was packed out every night. There was obviously no accounting for taste. The best hornpipe dance would win a free drink at the end of the night, but I’d never be in a sufficiently decent state to even attempt it. Although there were plenty of fights – mostly handbags – genuine violence was fairly thin on the ground among sailors. If there was any real trouble it tended to get started by the local thugs who wanted to put one over ‘Jolly Jack’ to prove that they still possessed the requisite manliness to survive in seaside cities they perceived as being ‘invaded’ by the Navy. All the recent debate about the disenfranchisement of the British working class is nothing new. I saw it first-hand in the mid-1980s on the streets of Plymouth and Portsmouth most Friday and Saturday nights.

* ‘Junior rates’ is the collective term for seamen, able seamen and leading hands.

† Submarine submerged nuclears – known as ‘hunter-killers’ – were nuclear-powered submarines that didn’t carry nuclear weapons.