How Corruption and Anti-Corruption Policies Sustain Hybrid Regimes

ibidem-Press, Stuttgart

Abstract

This book argues that leaders of hybrid regimes in pursuit of political domination and material gain instrumentalize both hidden forms of corruption and public anti-corruption policies. Corruption is pursued for different purposes including cooperation with strategic partners and exclusion of opponents. Presidents use anti-corruption policies to legitimize and institutionalize political domination. Corrupt practices and anti-corruption policies become two sides of the same coin and are exercised to maintain an uneven political playing field.

This study combines empirical analysis and social constructivism for an investigation into the presidencies of Leonid Kuchma (1994–2005), Viktor Yushchenko (2005–2010) and Viktor Yanukovych (2010–2014). Explorative expert interviews, press surveys, content analysis of presidential speeches, as well as critical assessment of anti-corruption legislation, provide data for comparison and process tracing of the utilization of corruption under three Ukrainian presidents.

Dr. Oksana Huss is a Research Fellow at Bologna University. She did her doctorate at the University of Duisburg-Essen and a postdoc at Leiden University. Huss taught at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy as well as the Kyiv School of Economics, and consulted for the Council of Europe, the EU, UNESCO and UNODC. She is a co-founder of ICRNetwork.org—the Interdisciplinary Corruption Research Network.

The authors of the foreword:

Dr. Tobias Debiel is Professor of International Relations and Development Policy at the University of Duisburg-Essen

Dr. Andrea Gawrich is Professor of International Integration at Justus Liebig University of Giessen

Table of Contents

Abstract

List of Abbreviations

Acknowledgments

Foreword

1. Introduction

1.1. The research puzzle

1.2. The research question

1.3. The central argument

1.4. Methods of data collection and analysis

1.5. The structure of this study

2. Conceptualizing corruption: Definitions, typologies and explanatory approaches

2.1. From worldview to the concept

2.2. Core characteristics of corruption

2.3. Varieties of corruption

2.3.1. Distinguishing context: Corruption as an exception vs. corruption as the norm

2.3.2. Distinguishing relevant forms of corruption

2.4. Corruption as an umbrella concept

2.4.1. Particularism and conflict of interest

2.4.2. Clientelism

2.4.3. Patronage

2.4.4. Control in clientelistic and patronage networks

2.4.5.Patrimonialism

2.4.6. State capture

2.5. System as an analytical concept for corruption clusters in hybrid regimes

2.5.1. Defining the system of corruption

2.5.2. Typology of the system of corruption

3. Combining constructivist and empirical-analytical perspectives on corruption

3.1. Constructivist perspective

3.1.1. Corruption as an empty signifier

3.1.2. From articulation to construction of social identities and institutions

3.1.3. Framing corruption as a tool in political tactics

3.1.4. The role of corruption and anti-corruption in hegemonic struggle

3.2. Theoretical explanatory approaches to corruption: Agency vs. institutions

3.2.1. Agency-centered micro-perspective

3.2.2. Institution-centered macro-perspective

3.3. Synthesis: Variety of corruption meanings as framing options

4. Conceptualizing hybrid regimes and the role of corruption in them

4.1. Hybrid regime concepts at a glance

4.2. Characteristics of hybrid regimes

4.2.1. Distinguishing hybrid regimes from democracy and authoritarianism

4.2.2. Uneven playing field

4.2.3. Power asymmetries in semi-presidentialism

4.2.4. The interplay of formal and informal institutions in hybrid regimes

4.3. Dynamic of hybrid regimes and the role of corruption

4.3.1. Scenarios of elite interaction and corresponding type of corruption systems

4.3.2. Operationalizing regime dynamics

4.4. Operationalizing actors’ action: political strategy and tactics in hybrid regimes

4.4.1. The interplay of structural context and individual actors’ action

4.4.2. Defining strategy and tactics

4.4.3. Actors’ strategic calculations in hybrid regimes: Goals, resources, environment

5. The system of corruption in Ukraine and its role in sustaining regime hybridity

5.1. The role of the oligarchs

5.2. A system of corruption model

5.2.1. Political parties

5.2.2. Elections

5.2.3. Political influence

5.2.4. Political outcome side

5.3. Synthesis: An uneven playing field as a result of corruption practices

6. Case study of the political domination of Leonid Kuchma: Functions and implications of the centralized system of corruption

6.1. Outset: Regime trajectory, power resources and constellation of actors

6.1.1. Fragmentation of power: Institutional and political competition

6.1.2. Points of reference for strategic interaction

6.1.3. Synthesis

6.2. Corrupt practices as tactics for political domination

6.2.1. Neo-patrimonial decision-making between 1994 and 1998

6.2.2. Change of the political domination strategy: From exclusion to co-optation

6.2.3. Patronage

6.2.4. Clientelism

6.2.5. Non-coercive control: Corruption-based kompromat and blackmail

6.2.6. Synthesis

6.3. Corruption framing as a tactic for political domination

6.3.1. Antagonism of strong principal and “invisible enemy”

6.3.2. Framing of corruption as a principal-agent problem

6.3.3. Suggested remedies

6.3.4. Crisis and change: Framing shift toward perpetual corruption in society

6.3.5. Popular attitudes

6.3.6. Synthesis

6.4. Assessment of the anti-corruption policies

6.4.1. Constellation of actors and control of corruption in early 1990s

6.4.2. Political domination by means of anti-corruption institutions

6.4.3. Conceptualization of corruption in legislation

6.4.4. Synthesis

6.5. Conclusion

7. Case study of the political domination of Viktor Yushchenko: Functions and implications of the decentralized system of corruption

7.1. Outset: Regime trajectory, power resources and constellation of actors

7.1.1. Renewal of the elite

7.1.2. Fragmentation of power: Institutional and political competition

7.1.3. Synthesis

7.2. Corrupt practices as tactics for political domination

7.2.1. Shifting towards a gray zone of governance

7.2.2. Favoritism under Yushchenko: Bargaining in patron-client networks

7.2.3. Synthesis

7.3. Corruption framing as a tactic for political domination

7.3.1. Antagonism of democracy and authoritarianism

7.3.2. Framing of corruption as a system

7.3.3. Crisis and change: Framing shift toward the concept of “political corruption”

7.3.4. Suggested remedies

7.3.5. Popular attitudes

7.3.6. Synthesis

7.4. Assessment of the anti-corruption policies

7.4.1. Constellation of actors and control of corruption

7.4.2. Conceptualization of corruption in legislation

7.4.3. Synthesis

7.5. Conclusion

8. Case study of the political domination of Viktor Yanukovych: Functions and implications of the monopolized system of corruption

8.1. Outset: Regime trajectory, power resources and constellation of actors

8.1.1. Subordination of state institutions

8.1.2. Synthesis

8.2. Corrupt practices as tactics for political domination

8.2.1. Particularism under Yanukovych

8.2.2. Monetary corruption: An instrument of exclusion and monopolization of power

8.2.3. Raising the “Family”

8.2.4. Synthesis

8.3. Corruption framing as a tactic for political domination

8.3.1. Antagonism of chaos and order

8.3.2. Functions of the empty meaning of “corruption”

8.3.3. Framing corruption as a principal-agent problem

8.3.4. Suggested remedies

8.3.5. Popular attitudes

8.3.6. Synthesis

8.4. Assessment of the anti-corruption policies

8.4.1. Constellation of actors and control of corruption

8.4.2. Conceptualization of corruption in the legislation

8.4.3. Synthesis

8.5. Conclusion

9. Conclusion

9.1. Synopsis

9.2. Comparative analysis

9.2.1. Assessment of the strategies

9.2.2. Comparison of political tactics

9.3. Key findings and implications for counteracting corruption

9.4. Prospects for further research

References

Secondary sources

Primary sources for the framing analysis

International Organizations: Documents, reports, assessments

Annex 1: Overview of the expert interview partners

Annex 2: List of online media for the search inquiry

Annex 3: MaxQDA code book

Annex 4: Anti-corruption legislation

List of Abbreviations

ACN OECD OECD Anti-Corruption Network for Eastern Europe and Central Asia

AntAC Anti-Corruption Action Centre

AP Administration of the President

BYuT Bloc of Yulia Tymoshenko

CSO Civil Society Organization

DRFC LLC Donbass Rozrakhunkovo Finansovyi Centr

EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

EEAS European External Action Service

EU European Union

GRECO Council of Europe’s Group of States against Corruption

IAHR Institute of Applied Humanitarian Research

IMF International Monetary Found

MP Member of Parliament

NAC National Anti-Corruption Committee

NGO Non-Governmental Organization

NiT index Freedom House Nations in Transit Index

NSDC National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine

NUNS Nasha Ukraina—Narodna Samooborona (“Our Ukraine”—People’s Self-Defense Bloc)

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OIG Office of the Inspector General

PACE Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

PGO Prosecutor General’s Office

PM Prime Minister

PUMB First Ukrainian International Bank

RUE RossUkrEnergo

SBU Sluzhba Bezpeky Ukrainy (Security Service of Ukraine)

SIDA Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency

SME Small and medium enterprises

TI Transparency International

UBD Ukrainian Bank of Development

UHHRU Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union

UN United Nations

UNCAC United Nations Convention against Corruption

UNDP United Nations Development Program

USA United States of America

USAID United States Agency for International Development

Acknowledgments

I am deeply indebted to many people for their support in completing this dissertation, without which the work would not have been realized. First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to Professors Tobias Debiel and Andrea Gawrich, my supervisors, for providing me with guidance, useful critiques and helpful encouragements. I highly appreciate the degree of freedom they gave me to unfold my research ideas and, at the same time, their guidance that allowed me to maintain steady development in my research. Constructive feedback on content and methodology, provided by the participants of the Ph.D. workshop “International relations/Peace and Development studies” was greatly valued. Therefore, I would like to thank the workshop’s organizers—Professors Tobias Debiel, Walter Eberlei, Christof Hartmann, Hartwig Hummel, Cornelia Ulbert and the team of the Institute for Development and Peace—for providing a comfortable space for the exchange and discussion of research ideas.

I would like to express my appreciation to the Hanns Seidel Foundation for the generous funding of my research. I am particularly grateful to Prof. Hans-Peter Niedermeier, Dr. Michael Czepalla and Prof. Rudolf Streinz for their support and sage advice in my professional life in academia and beyond. I also wish to acknowledge the generous research funding provided by the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) which enabled me not only to finalize my thesis but also to greatly profit from the valuable feedback of my Ph.D. fellows during colloquium and conference meetings. I am also grateful to the Petro Jacyck Foundation, which enabled my research stay at the University of Toronto, Centre for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies. In particular, I would like to thank Profs. Lucan Way and Matthew Light for the enriching discussions and valuable ideas exchanged during my research while at CERES. I would also like to extend my thanks to the Research Centre for East European Studies (Forschungsstelle Osteuropa—FSO) at the University of Bremen for hosting me during the data collection period and kindly providing access to their databases. Advice given by Prof. Heiko Pleines during my stay at FSO and after has been a great help in advancing my research.

My personal gratitude goes to Daria Kaleniuk, Dr. Oksana Nesterenko and Prof. Andriy Meleshevych, who involved me in the development and the work of the Anti-Corruption Research and Education Centre in Ukraine. I highly appreciate the possibility of lecturing anti-corruption activists and researchers in Ukraine, which allowed me to test and to improve my research ideas, as well as gain deeper insight into the topics of corruption and anti-corruption in Ukraine through continuous exchange with experts. I would also like to thank all interview partners, who shared their valuable expertise on the topic with me. In particular, I am grateful to Prof. Mykola Khavroniuk for his openness in providing me with highly appreciated legal expertise in the anti-corruption field on several occasions.

My Ph.D. research time became a highly exciting journey thanks to many young scholars, who were keen to develop the community of corruption researchers and dared ambitious joint projects in this field. In particular, the German-speaking KorrWiss network and the international Interdisciplinary Corruption Research Network became my “home in corruption research.” Among network founders and participants, respected colleagues like Aiysha Varraich, Anna Schwieckerath, Annika Engelbert, Eduard Klein, Ina Kubbe, Jamie-Lee Campbell, Jessica Flakne, Johann Steudle, Marina Povitkina, Nils Köbis, Sofia Wickberg, Steven Gawthrope became dear friends, who not only shared the same excitement for the research topic, but were always also open to constructive feedback and encouragement in the long research process, full of uncertainties and doubts. My sincerest thanks to you! My deep appreciation goes to the senior member of the ICRNetwork, Prof. Bo Rothstein, who not only provided valuable feedback on my research but also gave good advice and mentoring on academic work in general. Through mutual research and education projects with Oleksandra Keudel and Olena Petrenko I have learned how highly rewarding investing time in and contributing efforts to joint activities can be. Thank you both for being pleasant partners and supportive friends.

Finally, I would like to thank my family and foremost my husband for believing in me, backing me and giving me hope and strength in times of uncertainty. I highly appreciate your patience and support throughout this process.

Foreword

Although it is challenging to research corruption, this book provides an innovative conceptual and empirical contribution to both research areas, corruption and transformation studies alike. The study is based on a Most Similar Systems Design through an intra-case comparison of three presidencies: Leonid Kuchma (1994–2005), Viktor Yushchenko (2005–2010) and Viktor Yanukovych (2010–2014). The book investigates the following research questions: Why do presidents in Ukraine use different political strategies and discursive framings to address corruption? How do they utilize corruption as a tactic to maintain political domination in hybrid regimes?

The book applies both positivist and constructivist approaches. The empirical analysis reveals the role of corrupt practices in sustaining political domination. Furthermore, it demonstrates impressively that anti-corruption policies in a hybrid regime like Ukraine can be understood as discursive framing strategies applied by political leaders to ensure and legitimize their political domination.

The book studies how different regime trajectories under authoritarian or semi-democratic rule led to different corruption practices. In a cartel-like deal, Kuchma managed to construct a centralized system of corruption that traditionally framed the problem along a principal-agent approach. Yushchenko, on the other hand, could not centralize elites and attempted to secure power through a decentralized system in which he discursively emphasized European values in the fight against political corruption. However, he was unable to present himself credibly to the population as a politician of a new type. In a way, as Oksana Huss contends, he became the victim of his own discourse. Yanukovych, in turn, succeeded in monopolizing corruption because of his “political machine”, the Party of Regions. His political discourse remained deliberately vague and shaped by metaphors, which made it difficult to measure the success of anti-corruption policies.

Despite these differences, the three presidents shared a willingness to adapted their framing strategies to account for the constellation of their political opponents and addressed the expectations of external actors. Furthermore, their administrations were all initially supported by the population—and failed to adjust their strategies appropriately as their popularity ratings declined.

In summary, this book provides an important contribution in a challenging empirical research field. It corresponds to the state of the art and provides an in-depth case study based on an analytically attractive theoretical and methodological framework.

Dr. Tobias Debiel

Professor of International Relations and

Development Policy at the University of Duisburg-Essen

Dr. Andrea Gawrich

Professor of International Integration

at Justus Liebig University of Giessen

1. Introduction

Since the early 1990s, studies of transformation processes and hybrid regimes, as well as of corruption and anti-corruption policies, have intensified. The leading studies of hybrid regimes identified endemic political corruption as those regimes’ immanent characteristic (Åslund 2015; Hale 2015; Havrylyshyn 2017; Levitsky and Way 2010). Nevertheless, there is a lack of systematic research concerning the interdependence between hybrid regimes, their trajectories, and corruption (Pech 2009). This thesis aims to enrich transformation studies by incorporating corruption research and closing the knowledge gap between the “(dys)functionalities” of corruption practice and framing (Debiel and Gawrich 2013), in particular in hybrid regimes.

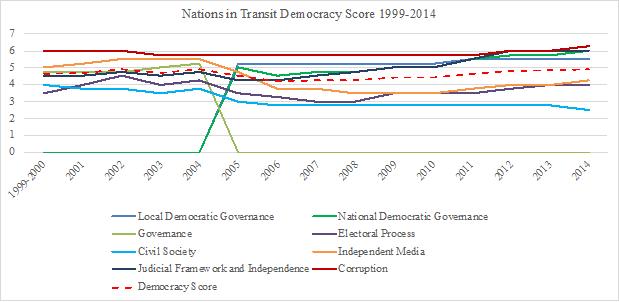

Ukraine demonstrates an appropriate empirical example to study such interdependencies. On the one hand, a turbulent transformation process and several regime oscillations occurred after the collapse of the Soviet Union. With regard to the transformation process, since its independence Ukraine has been host to three different regime trajectories of high volatility. The administration of President Leonid Kuchma (1994–2005) saw shades of authoritarian tendencies. After the Orange Revolution in November 2004–January 2005, hope grew for a democratic reorientation. Between 2010 and 2014, however, President Viktor Yanukovych reverted to the authoritarian trajectory, which was violently abandoned in the course of the Maidan Revolution in 2013–2014. Thus, the transition process in Ukraine has oscillated between semi-consolidated democracy and semi-consolidated authoritarianism but remains stable in its hybridity. On the other hand, rather counter-intuitively, through all these years, the level of corruption in Ukraine has perennially been well above average, even though Ukraine’s Freedom House democracy score improved between 2005 and 2009 (see Figure 1). Both revolutions—the Orange Revolution and the Maidan Revolution—were initiated because of widespread discontent among the population at corruption. During the Orange Revolution, electoral fraud was the spark that inflamed a popular uprising against the ruling elite. During the 2013–2014 Ukrainian revolution, one of the main demands of the protesters included the removal of the corrupt Yanukovych regime and punishment of those involved in political corruption.1

Figure 1: Freedom House Nations in Transit democracy score 1999–2014

Source: Freedom House Nations in Transit democracy score, 1999–2014. Author’s depiction. The score 1–2.99 indicates consolidated democracy, 3–3.99 Semi-consolidated democracy, 4–4.99 Transitional or hybrid regimes, 5–5.99 Consolidated authoritarian regimes, and 6–7 Consolidated authoritarian regimes. In 2005, due to methodological changes, “governance” was divided into two subjects of analysis—national and local democratic governance. Available online at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2017/ukraine, last accessed 21 June 2018.

Within Ukraine, this book analyzes three cases of corruption framing and practice for political domination under Leonid Kuchma (1994–2005), Viktor Yushchenko (2005–2010) and Viktor Yanukovych (2010–2014). The reason for this focus is the decisive role that presidents have due to Ukraine’s semi-presidential political system (Carrier 2012; Choudhry et al. 2018; Matsuzato 2005; Protsyk 2003).

1.1. The research puzzle

The concept of competitive authoritarianism (Levitsky and Way 2010) forms the main theoretical framework for the assessment of transition processes in Ukraine in this study. The definition of competitive authoritarianism is based on the partial relevance and selective application of formal democratic rules. Political competition and the existence of an uneven playing field between incumbents and the opposition are crucial for this concept. The in-between-ness between democracy and authoritarianism is an important characteristic of competitive authoritarian regimes. As with democracies, in competitive authoritarianism elections shape actors’ strategies, even though competition is not necessarily fair. Because elections are not merely a façade, wide popular support is highly desirable to remain in power. At the same time, similar to authoritarian regimes, incumbents are able to manipulate state institutions and resources to such a degree that political competition is seriously limited. Another limitation is that ruling elites are fragmented, and control over political, administrative and economic resources is divided among several oligarchic groups. In this situation, to strengthen political power and to secure co-optation of elites, incumbents need to gain the acceptance and support of elite networks. The constant need of incumbents to balance between public and elite support under conditions of competitive authoritarianism makes corruption a controversial issue for the ruling elite. This controversy constitutes, in turn, the research puzzle of this project.