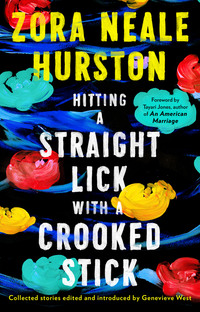

Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick

The narrative names Porter David as the artist who created the painting that captures Lilya at her best. His name, as Carpio and Sollors astutely point out, evokes the painter James A. Porter, a 1927 Howard graduate.38 While Carpio and Sollors suggest “the world in a jug” reference in the story constitutes an “uncanny anticipation” of Porter’s award-winning painting Woman Holding a Jug, it seems more likely that both Hurston and Porter allude to the blues song “Down Hearted Blues,” which made Bessie Smith famous in 1923.39 Like so many blues songs, this one chronicles a broken relationship. Smith, however, puts her own stamp on the song by reorganizing the lyrics to emphasize the blues singer’s resilience. Although Smith’s man has left her, she still believes that she has “got the world in a jug—the stopper’s in my hand.”40 In Hurston’s story, the line “the world in a jug” appears in the opening paragraphs, foreshadowing the ending, in which the male characters leave Lilya behind.

“Monkey Junk” (1927), another recovered story, also evokes an element of Harlem life that is unlike anything else in Hurston’s work. Although funny, it is perhaps the author’s most cynical look at relationships between men and women. The narrative juxtaposes the high and low in mock biblical chapters, much like “Book of Harlem” and “The Book of Harlem.” “[M]ixed up proverbial wisdoms” like ‘He that laughest last is worth two in the bush,’ Carpio and Sollors note, provide much of the humor.41 Beneath this humor, however, Hurston takes her “crooked stick” to both genders. The plot unfolds as an unnamed man journeys out of the South to Harlem. He believes he “knoweth all about women,” and by story’s end that overconfidence has cost him dearly. He is trapped by a woman infatuated with his checkbook. As a consequence of underestimating the power of feminine wiles and overestimating his own skills, the exploited and outmatched husband finds himself responsible for a hefty alimony payment. It is easy to laugh as the unnamed woman takes advantage of his arrogance. At the same time, however, Hurston also interrogates the way the woman exercises her agency. In divorce court the judge and jury view her as a woman in need of rescue when nothing could be further from the truth. As readers watch the woman lie and manipulate, her performance becomes central. Admittedly, as Carpio and Sollors point out, she is hardly a feminist role model. And yet, she uses what she has—her appearance—to achieve her ends in a patriarchal culture. Through the introduction of the woman’s lawyer, Hurston “hit[s] a straight lick.” He is the only man who sees through the woman’s performance. Through his character, Hurston cautions readers to avoid being like the “doty juryman” and instead to see beneath the surface of gendered performances.

“The Country in the Woman” and “She Rock” also explore the impact migration has on identity and marriage, as well as the tensions between rural and urban life. The plot of both stories revolves around Caroline, a married woman who uses her ax to end the affairs of her philandering husband. This pattern appears four times across the body of Hurston’s work. Rural versions of the tales set in Hurston’s hometown of Eatonville, Florida, appear in “The Eatonville Anthology” (collected here) and in her autobiography. In “The Country in the Woman” and in “She Rock,” Hurston relocates the plot to Harlem to critique urban constructions of female identity.

“The Country in the Woman” (1927) focuses narrowly on Caroline and her wayward husband in Harlem. In exchanges between Caroline and her husband, Mitchell, readers see Caroline perform for her audiences. The story opens on a Harlem street as Caroline confronts Mitchell and his “side gal.” Rural African American vernacular permeates Caroline’s speech, as she threatens the other woman: “I’ll kick her clothes up round her neck like a horse collar. She’ll think lightnin’ struck her all right, now.” A “dark brown lump of country contrariness,” this wife has publicly and humorously vanquished previous rivals when the couple lived in the South, but Mitchell mistakenly believes that in urban Harlem he can carry on an affair without her knowledge. Mitchell has adopted “Seventh Avenue corners and a man about town air” and a new, store-bought wardrobe. Caroline, however, continues to sleep in “yellow homespun.” Because homespun cloth and the clothing it became were made in the home, that nightgown symbolizes the independence necessary for the survival of rural women like Caroline. Her idioms and her “‘way-down-in-Dixie’ look” also foreshadow the rural weapon Caroline will use to end Mitchell’s liaison. Readers laugh at the humorous conflict between husband and wife and between rural and urban norms as Caroline emerges the victor by rejecting conventional, urban, middle-class norms of femininity.42

The final and latest of the recovered stories is “She Rock.” In 2004, Hugh Davis noted his discovery in The Zora Neale Hurston Forum.43 He serendipitously found it while browsing the Courier for the writings of another Harlem Renaissance scribe, George Schuyler.44 Written in 1933, “She Rock” explores the same central plot as “The Country in the Woman,” but in this version traditional narration gives way to the numbered mock biblical chapters and verses that Hurston had employed in “The Book of Harlem” and “Monkey Junk.” In “She Rock” Hurston allows readers to migrate with Caroline and her husband when Oscar’s brother recruits him to work for the “Kings and Princes in Great Babylon” to earn “many sheckels.” Once in the city, Oscar is advised to “shake that thing,” and he does, as Hurston riffs on the Ethel Waters hit by the same name: “Yea, shook the fat with the lean, the rich with the poor; the aged with the young, verily was there not a shaking like unto this before nor after it.” More explicitly than in “The Country in the Woman,” Hurston critiques the relationship between Oscar and his girlfriend. The portraits are funny but unflattering. He is arrogant, and she is a gold-digging manipulator. The result of Hurston’s revisions is a less playful tale, one more critical of New Negro gender constructions that would keep Caroline passively at home while her husband roams the streets with another woman.45

EXPLORING THE POLITICS OF RACE AND CLASS

Hurston’s fiction interrogating race receives less attention than it should, particularly given that her more direct treatments of race and power appear in stories in which she blends folklore and fiction. African American folklore, particularly in song and story, serves important functions within the black community. It also has a long history as a weapon in the fight against slavery and racism. While Zora’s treatment of race differs considerably from the angry, confrontational work of her contemporary Richard Wright, her fiction nevertheless explores what it means to be black in America. Her decision to write about black communities with white characters appearing only on the fringes—if at all—is a political choice, one that marginalizes whites and puts African Americans at the center and affirms that black folk are worthy of stories. As we have seen, using her “crooked stick” Hurston strikes at the intraracial politics of complexion, called colorism or shadeism, which exists in dialogue with whiteness and the belief that lighter is somehow better. Likewise, her fiction resists New Negro attempts to rehabilitate the image of blacks in the eyes of the whites by shunning folk culture as backward, ignorant, or undesirable. These are intentional treatments of race that Wright and his contemporaries overlooked.46 But Hurston also wrote stories that address race more directly. She turned to folklore to do so.

The neglected story “Black Death” apparently never appeared in print in Hurston’s lifetime. She submitted it to the 1925 Opportunity literary contest, where it won honorable mention.47 All evidence suggests the story waited until the appearance of The Collected Stories (1995) to finally find an audience, perhaps because it explores conjure’s role in a southern black community. Like “Spunk,” the story illustrates the ways in which the weak take their vengeance on the strong. Fiction and folklore blend in “Black Death,” blurring the lines between genres. The frame for the plot of “Black Death” reads like an essay and emphasizes different ways of knowing, illustrating that blacks know and understand things about the world that whites do not. At the heart of the story is a lothario who comes to town, seduces a girl he works with, and abandons her when she becomes pregnant. The girl’s mother, distraught and helpless in this world, turns to Old Man Morgan, the local conjure man, for justice. Hemenway tells us that both the lothario’s name, Beau Diddely, and the plot itself are “traditional,” and they exist elsewhere in Hurston’s anthropological publications.48 Clearly, then, the story is not entirely fiction, but Hurston transforms the folktale, frames it, and, like Charles W. Chesnutt did before her in his conjure tales, reveals the ways in which power works—in the material world and beyond. While some middle-class readers might have been put off by or embarrassed by a conjure story, Hurston’s pride in her culture prevented any such discomfort for her. Further, the frame of the story suggests that whites are inferior because they live only in a material world and thus fail to understand the additional dimensions of the spirit world.

In “’Possum or Pig” (1926) Hurston takes a similar approach by blending genres. Julius Lester, the African American storyteller, explains that folklore is like water in that as it passes from one pitcher to another “its essential properties are not harmed or changed … . A folktale assumes the shape of its teller.” 49 Hurston’s oral performances at parties were legendary, and here she may well have transferred to paper part of her repertoire for the magazine Forum, where editors included commentary praising the value of African American folklore and supporting the New Negro movement. Set in the days before emancipation, the story features a plot that hinges on John, the classic African American trickster figure, who has stolen and butchered one of Master’s pigs. When Master comes to John’s cabin, the pig is steaming in a pot above the fire. Unable to deter Master from entering his humble cabin without enduring a whipping, John claims to be cooking a “dirty lil’ possum”: “Ah put dis heah critter in heah a possum,—if it comes out a pig, ’tain’t mah fault.” The open-ended tale emphasizes John’s willingness to match wits with his master, and readers pull for the less powerful character. Lurking beneath the surface, however, are also the larger dynamics of American slavery. John steals pigs to feed himself because he is not provided enough to eat. His cabin is not his own. The man defined by law as his “owner” can do what he wills to John without fear of retribution. John must use his wits to survive. The seriousness of this history embedded within a funny, traditional tale reveals Hurston “hitting a straight lick with a crooked stick” to address the politics of race, which had evolved painfully little in the years between emancipation and the Harlem Renaissance, especially for those sharecropping in the South.

Near the end of the period, Hurston published one of her finest stories, “The Gilded Six-Bits” (1933), which offers one of her most direct critiques of the politics of race. Her critique is embedded in an interesting reversal of other migration stories (in that one of the characters migrates south) and provides a subtle interrogation of masculinity. In its conclusion, however, Hurston turns the reader’s attention to the politics of race. When “The Gilded Six-Bits” appeared in Story magazine, it caught the attention of editors at J. B. Lippincott and ultimately led to the publication of Hurston’s first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine. Again, the complexities of marriage take center stage in a love triangle, but this time a northerner participates in reverse migration when he moves from Chicago to Eatonville to open an ice cream parlor. There he meets Joe and Missie May, a young married couple. Joe puts the urbanite on a pedestal, talking repeatedly about this urban interloper with “de finest clothes … ever seen on a colored man’s back” and a five-dollar gold coin for a lapel pin. Missie, on the other hand, seems decidedly unimpressed. Readers then are almost as shocked as Joe is to find Missie and the northerner in bed together. When Joe discovers the affair, he also finds that the gold pin he had admired is nothing more than a gilded coin. It and the urbanite are both fakes. Things are not always as they seem. In the final lines, Hurston turns this story about love and marriage to illuminate yet another way in which appearance and reality collide, this time in the politics of race. She confronts readers with racism in the one scene in which a white character appears. When Joe finally spends the northerner’s gilded coin in a local shop, the white store clerk articulates the stereotype he has imposed on Joe: “Wisht I could be like those darkies. Laughin’ all the time. Nothin’ worries ’em.” The ironic claim rings hollow for readers who know just how painful the acquisition of that gilded coin was for Joe. The clerk’s use of the term “darky” reveals that he sees Joe as a minstrel figure untroubled by the woes of the modern world. Through dramatic irony, Hurston points out that Joe’s life is far more complicated than the racist clerk can imagine. The line contrasts what readers, white and black, know about Joe’s life with what the clerk thinks he knows. In this way, Hurston undermines the stereotype, revealing its distortion of a man’s complex humanity.

THE END OF THE ERA

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Hurston took a break from writing short fiction as she traveled the South collecting African American folklore. During this period she drafted the material that would eventually become three distinct books: Mules and Men (1935), Every Tongue Got to Confess: Negro Folk-tales from the Gulf States (2001), and Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” (2018). She and Langston Hughes fell out over their failed collaboration on Mule Bone in 1929, which did not appear in print until 1991. And she worked to bring authentic folk performances to the stage to great critical acclaim but with little financial success.50 Zora’s fiction was changing, too. The last story from Hurston’s Harlem Renaissance years, “The Fire and the Cloud” (1934), marks a significant departure from her earlier stories in terms of themes, characters, and settings. There is no love triangle, no Eatonville or Harlem settings, no vernacular speech. Instead, “The Fire and the Cloud” focuses on the Old Testament figure of Moses. Hurston’s attention has shifted from identity politics to the complexities of leadership. “The Fire and the Cloud” appeared five years before her novel Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939), in which she develops Moses as a magical figure—a masterful hoodoo practitioner, one not only dependent on God but powerful in his own right. Building on a long tradition of the Exodus story serving as an inspiration in African American culture, Hurston shifts the focus from the plight of the people being led out of bondage to the struggles of the leader. In the short story, readers see Hurston exploring for the first time the isolation and burdens of leadership. Set in the days after Moses has led the people to the Promised Land, the story opens on a mountain where the great liberator sits overlooking his people. Although seemingly without companionship, Moses strikes up a series of conversations with a lizard, in which he reveals he is alone after forty years of leadership. He is unconvinced that the people he served will remember or appreciate his sacrifices. After all, he points out, “The heart of man is an ever empty abyss into which the whole world shall fall and be swallowed up.” At the end of thirty days on the mountain, Moses symbolically inters his role as leader and walks away, leaving his powerful staff leaning on the pile of stone. He passes the role of leader to Joshua, who will find the staff and assume that Moses has passed away. The story’s conclusion literally and symbolically severs the role of leader from the human being who assumes the mantle, suggesting it is a performative role. While followers might naively put their leaders on a pedestal and idealize them, leaders take on the role their followers need them to assume, sometimes at great personal cost.

In the years between “The Fire and the Cloud” and Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), Hurston traveled to Haiti and Jamaica on two prestigious Guggenheim fellowships. She wrote the novel on her first trip as she tried to “smother [her] feelings” after leaving her longtime love affair behind in the United States. “The plot was far from the circumstances, but I tried to embalm all the tenderness of my passion for him in ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God,’” she writes in her autobiography.51 While Hurston’s black contemporaries were critical of the book when it appeared because it did not explicitly confront class issues, it has been largely responsible for her ascending to the canons of American literature.52 When the author returned to the United States after her fellowships in 1938, she would focus on producing books and essays. The peak of her productivity as a short story writer was behind her.

Almost a century later, Hurston’s contributions to American literary culture continue to inform the ways we talk about the Harlem Renaissance, Modernism, women’s literature, folk literature and folklore, ethnography, migration fiction, and Southern literature. Her groundbreaking stories and bodacious personality have made her one of the most-storied and most-studied Harlem Renaissance writers. Hurston’s finest stories have made her a hypercanonical figure, a giant of the twentieth century, an icon. This collection of Hurston’s Harlem Renaissance short fiction, particularly the addition of once-lost stories to her canon, requires readers to rethink her legacy. In these recovered stories, we see her explore the urban experience and the educated New Negro, two elements of Harlem Renaissance culture that seemed to have been lacking in her oeuvre. We see her use her “crooked stick” to critique the politics of gender, class, and race. Situated within the better-known body of Hurston’s work, as they are in this volume, these recovered stories reveal the broader scope of her writings, both in terms of theme and form. Hurston’s keen ear for vernacular speech, her devotion to depicting proudly and completely the folk she knew, and her persistent attention to the intersections of race, class, and gender have left us a beautiful, complicated, and unsurpassed legacy of Harlem Renaissance short stories.

Genevieve West

October 22, 2019

John Redding Goes to Sea

The Villagers said that John Redding was a queer child. His mother thought he was too. She would shake her head sadly, and observe to John’s father, “Alf, it’s too bad our boy’s got a spell on him.” The father always met this lament with indifference, if not impatience.

“Aw, woman, stop dat talk ’bout conjure. ’Tain’t so nohow. Ah doan want Jawn tuh git dat foolishness in him.”

“Case you allus tries tuh know mo’ than me, but Ah aint so ign’rant. Ah knows a heap mahself. Many and manys the people been drove outa their senses by conjuration, or rid tuh deat’ by witches.”

“Ah, keep on telling yur, woman, ’taint so. B’lieve it all you wants tuh, but dontcher tell mah son none of it.”

Perhaps ten-year-old John was puzzling to the simple folk there in the Florida woods, for he was an imaginative child and fond of daydreams. The St. John River flowed a scarce three hundred feet from his back door. On its banks at this point grew numerous palms, luxuriant magnolias and bay trees with a dense undergrowth of ferns, cat-tails and rope-grass. On the bosom of the stream float millions of delicately colored hyacinths. The little brown boy loved to wander down to the water’s edge and cast in dry twigs, and watch them sail away down stream to Jacksonville, the sea, and the wide world and John Redding wanted to follow them.

Sometimes in his dreams he was a prince, riding away in a gorgeous carriage. Often he was a knight bestride a fiery charger prancing down the white shellroad that led to distant lands. At other times he was a steamboat Captain piloting his craft down the St. John River to where the sky seemed to touch the water. No matter what he dreamed or whom he fancied himself to be, he always ended by riding away to the horizon, for in his childish ignorance he thought this to be the farthest land.

But these twigs, which John called his ships, did not always sail away. Sometimes they would be swept in among the weeds growing in the shallow water, and be held there. One day his father came upon him scolding the weeds for stopping his seagoing vessels.

“Let go mah ships! you old mean weeds, you!” John screamed and stamped impotently, “They wants tuh go ’way, you let ’em go on.”

Alfred laid his hand on his son’s head lovingly. “What’s mattah, son?”

“Mah ships, Pa,” the child answered weeping. “Ah throwed ’em in to go way off an them ole weeds won’t let ’em.”

“Well, well, doan cry. Ah thought youse uh grown up man. Men doan cry lak babies. You mustnt take it too hard bout yo ships. You gotter git uster things gitten tied up. They’s lotsa folks that ’ud go ’on off too ef somethin didn’ ketch ’em and hol’ ’em!”

Alfred Redding’s brown face grew wistful for a moment, and the child noticing it asked quickly, “Do weeds tangle up folks too, Pa?”

“Now, now chile, doan be takin’ too much stock of what ah say. Ah talks in parables sometimes. Come on, le’s go on tuh supper.”

Alf took his son’s hand, and started slowly toward the house. Soon John broke the silence.

“Pa, when ah gets as big as you ah’m goin’ farther than them ships. Ah’m going to where the sky touches the ground.”

“Well, son, when ah waz a boy, ah said ah waz going too, but heah ah am. Ah hopes you have better luck than I had.”

“Pa, ah betcher ah seen somethin in th’ wood that you ain’t seen.”

“What?”

“See dat tallest pine tree ovah dere how it looks like a skull wid a crown on!”

“Yes, indeed,” said the father looking toward the tree designated, “it do look lak a skull since you call mah ’tention to it. You ’magine lotser things nobody evah did, son.”

“Sometimes, Pa, dat ole tree waves to me just after th’ sun goes down, an’ makes me sad an’ skeered too.”

“Ah specks youse skeered of de dahk, thas all, sonny. When you gits biggah you wont think of sich.”

Hand in hand these two trudged across the plowed land and up to the house—the child dreaming of the days when he should wander to far countries, and the man of the days when he might have—and thus they entered the kitchen.

Matty Redding, John’s mother, was setting the table for supper. She was a small wiry woman with large eyes that might have been beautiful when she was young, but too much weeping had left them watery and weak.

“Matty,” Alf began as he took his place at the table, “dontcher know our boy is different from any othah chile roun’ heah. He ’lows he’s goin to sea when he gits grown, an’ ah reckon ah’ll let ’im.”

The woman turned from the stove, skillet in hand. “Alf, you aint gone crazy is you? John kaint help wantin tuh stray off, cause he’s got a spell on ’im, but you oughter be shamed to be encouragin’ ’im.”

“Aint ah done tol you forty times not tuh tawk dat low-life mess in front of mah boy?”

“Well, if taint no conjure in de world, how come Mitch Potts been layin’ on his back six mont’s an’ de doctah kaint do ’im no good? Answer me dat. The very night John wuz bawn, Granny seed ole witch Judy Davis creepin outer dis yahd. You knows she had swore tuh fix me fuh marryin’ you ’way from her darter Edna. She put travel dust down fuh mah chile, dats what she done, to make him walk ’way fum me. An’ evah sence he’s been able tuh crawl, he’s been tryin tuh go.”

“Matty, a man doan need no travel dust tuh make ’im wanter hit de road. It jes comes natcheral fuh er man tuh travel. Dey all wants tuh go at some time or other but they kaint all git away. Ah wants mah John tuh go an’ see, cause ah wanted to go mahself. When he comes back ah kin see them furrin places wid his eyes. He kaint help wantin tuh go cause he’s a man chile.”