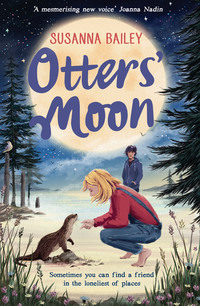

Otters' Moon

‘Jenny’s baby,’ Mum says, her voice quiet now. ‘It’s due next week. It won’t be a good time at your dad’s. I’m sorry, love.’

That’s when I get it, this island thing. Mum’s put an entire sea between her and Dad and Jenny’s cosy new family event.

Suddenly, Dad’s is the last face I want to see any time soon.

‘Jenny’s cooking sucks, anyway,’ I say. ‘I pity that kid of hers.’

Mum makes us an early breakfast. Pancakes and maple syrup. My favourite. I eat four to please her, even though I’m not hungry.

While I eat, the light changes. Grey shadows slide across the kitchen, suck out its colours. Rain scatters at the windows. Warning shots of worse to come, I know.

I go up to my room to get my warm sweatshirt; try to work out what on earth I’m going to do in this weather. I open up my laptop, check for a reply from Dad. Nothing.

Then I see him. Meg’s grandad. Out on the cliff, way too near the edge. Hard to be sure, but from my window it looks like he’s wearing pyjamas.

As I watch, there’s a deafening crack of thunder. A flash of white light. It’s the most exciting thing that’s happened since I arrived on the island. The old guy just stands there. He’s going to get struck by lightning. Or fall to his death.

I grab the waterproofs I swore I would never wear, run downstairs; pull on my boots at the door. As I rush down the path towards the old man, laces flapping, the light comes again. Disappears. Comes again.

Not lightning, then.

The old man is signalling. A huge lamp swings from one of his skinny arms. I call out, and he turns, his face skeletal in the lamplight. He stares at me for a moment, drops the lamp, staggers towards me, arms outstretched. His fingers claw at the air, reaching for me. They are gnarled and as stiff as twigs.

I freeze, not sure what to do.

‘Stay still.’

Meg again. This time, I’m pleased to see her.

‘Come on, Grandad,’ she says. ‘We can go home now.’

The old man smiles at her. Creases and crevices open up across his face.

Meg puts her arm round his shoulders; tries to lead him forward. He grabs my arm. His hand is mottled; dry. Like discarded snakeskin.

‘David,’ he says. ‘David.’

‘David’s coming, Grandad,’ Meg says, guiding him away.

‘Who’s David?’ I say.

Meg looks back at me over her shoulder.

‘You are,’ she says. Her eyes burn blue.

I get to the boathouse before Meg and her grandfather. She must have taken him the long way round, avoiding the steep cliff path I took. Once I’d decided I was going to come. Anything’s better than sitting in our grey cottage waiting for an email that will probably never arrive. And I’m kind of intrigued by this ‘David’ thing: who he is, why the old guy got so worked up about him.

I’m not sure I want to go into the house, though. Judging by the outside, it’s going to be pretty rank.

I walk right round the building. The walls are made of strips of wood. Grubby white paint is peeling from them. The whole place looks like it’s wrapped in dirty old bandages. Creeping plants hang in shrivelled strands from the roof. When I reach for one, it crumbles to dust in my hand.

There are boards nailed over every single window.

It’s a house with no eyes.

I look back across the beach. No sign of Meg and her grandfather, so I wander towards the dunes behind, hoping for a sheltered place to wait. Or maybe somewhere I can be out of sight while I rethink this whole idea.

Then there’s this flapping sound.

Half expecting some mythical sea creature to rise up and snatch my head from my shoulders, I follow the noise, which is growing louder and more frantic by the second.

Brave of me, or a symptom of boredom, I guess. Probably the latter.

There are a couple of white twisted trees in my path, their branches locked together like the bones of battling dinosaurs. As I squeeze between them, the wind gets colder, lifts the hairs on my arms, bites at my ears.

There is no monster in the dunes.

I knew that.

But there is something.

A great bulk, covered in tarpaulin, nestles in the dip between two sandbanks. It’s criss-crossed with thick ropes, pinned down like Gulliver. A corner of the tarpaulin has come free and is lifting and falling in the wind.

I make my way down there, sliding in the dry sand, and peer in through the flap. A putrid stench of fish and mould hits me.

I can’t see too well at first; have to tug more of the covering free, let in more light. There’s a faint scuttling sound as I do. A crab drops from somewhere above my head, makes me jump.

It’s a sailing boat. It was a sailing boat.

The old hull is slung with spiders’ webs, thick and greying like layers of old rag. Barnacles cover the edges and sides of the boat as far as I can see. They’re cold and sharp under my hand. I think suddenly of a shell-covered box my nan had on her dressing table.

She found me playing with it once, and that’s the only time she ever shouted at me. After she died, when we were sorting all her stuff, I looked inside. There was a ring, and a scrap of hair, which Mum said had belonged to Nan’s father. It grossed me out. But Dad got all sentimental, going on about how you don’t really lose someone when they die because you always have your memories.

Ironic, really. He’s managed to get lost pretty effectively and he’s still alive.

I pick up a twig from the sand, jab it among the cobwebs; tear at them, as far as I can reach. They’re disgustingly tough. I clear enough to make out mast and rigging, folded down the length of the boat like the wings of a great bird that lay down here to die.

‘Hey! Leave that.’

Meg is shouting, screaming, really, from above. I jump, drop the tarpaulin.

What the hell’s the matter with her? I’ve had it with her making me feel like I’m in the wrong.

‘Don’t worry, I’m off,’ I call up to her. I wipe my hands on my jacket. ‘And I won’t be back.’

The old man’s face appears beside Meg’s. He beckons to me and says something I can’t hear.

‘No, look, sorry – just come up, OK? Please. Sorry,’ Meg says. ‘I’ll explain . . .’

It looks like she is reassuring her grandad, trying to stop him coming down to join me.

‘Don’t even know why I’m here in the first place,’ I shout. But I scramble up the slope to join them, anyway.

‘OK, OK, just, just come in, all right? It’s too cold for Grandad out here and I’ll never get him inside unless you come too. Not when he’s like this.’ Meg fiddles with the lock on their faded front door.

I’m not sure again and look at my watch. ‘Actually, I should get back. My mum, she’s – I said I’d do lunch.’

Meg ignores me. The door is open now, and she’s reaching inside. Yellow light pours out. There’s a warm smell, like someone’s been baking.

I go in. I don’t mean to, but I do. Curiosity wins, I guess.

The old man relaxes once we’re all indoors. Meg helps him out of his jacket and boots, settles him in an armchair; fills a kettle. I stand there, staring around me.

The boathouse is bigger than I expected; brighter. There’s a wood-burning stove like the one Mum wants, and a kind of kitchen along one wall. Pots and pans are crammed on to shelves and hang from hooks around a miniscule cooker. There’s a cracked white sink. Dad has one like it in his new garden, with orange flowers growing inside. For salads, he says.

He never even cut the grass at our place.

The rest of the room is a cross between a small museum and a carpenter’s workshop. One where there’s been a small explosion. Wood carvings: intricate boats, tiny birds, a plane, various half-finished creatures and chunks of wood litter every surface. The dining table is covered in dusty newspaper. Curled wood shavings are scattered across it. More drift around the floor. A glass case above the hearth holds some sort of eel, frozen in mid-swim among stones and seagrass. On the window seat there’s something horribly like a stuffed baby seal.

There are jars containing mysterious shapes suspended in cloudy liquid. The labels are old, unreadable. I’m glad. Really, I don’t want to know.

You can’t see the walls for photographs. Faded black-and-white shots, mainly: young soldiers; smiling girls with coiled hair; ships with guns; a toothless guy holding a massive fish over his head, a stiffly posed wedding photo. The bride has a horseshoe for luck. I bet she needed it.

The few colour prints are of schoolkids with gappy smiles and lopsided ties. One of them might be Meg.

‘We’ve only got tea.’ She’s beside me, holding out a mug and trying to make room for a plate of biscuits on a small shelf, next to the skeleton of a lizard. ‘Home-made,’ she says. ‘The biscuits, not the lizard.’

‘Thanks,’ I say, wondering if they’re edible. I take one anyway, because I’m starving, and dip it in my drink. A chunk falls off and sinks to the bottom. I pretend not to notice, eat the rest in one bite. It’s good. I scan the whole room again, still unsure about entering this weird world. But at least it’s interesting. Being here beats hanging about with crabs. Or worrying about absent parents.

‘This place is crazy!’ I say, swallowing quickly. ‘All this stuff . . . is it his?’ I nod at the old man, asleep now, in his chair.

Meg holds her finger to her lips. She picks up the plate of biscuits, balances her mug of tea on it.

‘Hang on a minute.’ She opens a door at the end of the room, flicks a switch, bathing the walls in a wavering blue light that makes them look like they’re underwater.

It’s her bedroom.

She beckons me over, flops into a chair by the bed; smiles at me. It’s the first time I’ve seen her smile. She looks different. Which makes me more uncomfortable than I already am about being in the doorway of her bedroom.

I’m not exactly an expert on girls’ rooms, but Meg’s has to be unusual. It’s full of books, neatly stacked. The walls are bare except for a bunch of childish sketches: stick people with huge faces and big smiles; animals with lots of legs; some careful pencil sketches of round-eyed, whiskered animals leaping and diving on roughly torn paper. There’s a desk with an ancient PC, and, by the bed, a battered suitcase with a framed photo on top. That’s it. No clothes lying round, no boy band posters. No nail polish stains on the carpet like my mate Jez’s sister gets grounded for pretty much every week. No carpet.

‘Have the chair,’ Meg says, getting up, ‘if that makes you feel better.’

‘I’m all right,’ I say. I perch on the edge of the bed and work on looking cool. ‘So what is he, then, your grandad, some kind of collector?’

Meg flops back into her seat. ‘He’s lots of things. He’ll tell you when he wakes up.’

‘I don’t have much time.’ I glance at the old man. If he’s anything like my own grandad was, he’ll sleep the rest of the day. I’m not staying in weird-world that long. ‘Like I said, I’ve got to be back for lunch,’ I say. Which is true. ‘And I have to go to the shop first.’ Not true at all.

‘Next time you come, then. But the wooden things, Grandad makes those. The rest – the specimens and things, they’re mine.’

She actually looks proud.

‘That mangy seal is yours?’ I say, irritated at the way she assumes I’ll be back. Wondering whether I want to know this annoying girl at all. Even if she is the only one on the island who’s shown any interest in me. ‘And the Frankenstein’s lab stuff – those disgusting jars and dry bones?’

‘My parents’ work, mostly,’ she says. She sticks out her chin. ‘I told you, if you were even listening, they were marine biologists.’

Her parents. Both gone. She told me that too. She didn’t tell me why. Or where they are now.

I reach for another biscuit and bite into it, unsure whether to ask about them. The crunch is ridiculously loud, so I put the rest on my knee.

‘It’s the bonemeal that gives them their crunch,’ Meg says. ‘An old local recipe: puffin bones.’

I stare at her; feel as if I might throw up.

She laughs, forgetting to be quiet. The sound bounces round the room like a bubble.

I laugh too. First time in a while.

‘Hilarious,’ I say. I pick up a thick book from the pile nearest to me and flick it open. It’s full of shots of what look like shells, or stones with slimy underbellies. There are excited blocks of pink and yellow highlighter all over the text.

‘Offshore crustaceans,’ Meg says. ‘Fascinating.’

Not the word I would have used.

‘You’re seriously into this stuff, then?’

She nods. ‘It’s in my genes, Grandad says. My first word was “crab”, apparently.’ She leans back in her chair and crosses her legs. One foot taps in the air. ‘What’s your thing, then? We know it’s not wildlife or the great outdoors.’

I shrug. ‘Football and music. Mainly music. Guitar.’

‘You any good? D’you have lessons?’

‘My dad plays,’ I say. I clear my throat. ‘He teaches – taught – me.’ I look away, in case the twist of loss in my stomach shows in my face.

Meg’s foot is still. The air is still. I shift in my seat, just to make something move.

‘What kind of stuff do you play?’ Meg leans forward, chin in hands.

‘This and that. I was starting up a band back home. With my mates . . .’

‘And?’

‘Now I’m not.’

‘Why?’

‘Things got complicated.’

‘What kind of complicated?’

‘Just complicated.’

She looks me straight in the eye. I lean round and pick up the framed photo – there’s a woman with hair like Meg’s wearing a long flowery dress, a man with a tiny girl on his shoulders. They look happy.

‘My birthday,’ Meg says. ‘I was three. We had a picnic on the beach: pink cake and everything. This massive seagull stole some out of my hand. Dad chased it for miles just to make me laugh, Grandad says.’ She nods at the photo in my hand. ‘I can just see my dad, hobbling back up the beach with his flip-flops in his hand and a silly grin on his face.’ She looks away, stares for a moment at the boarded window opposite.

I gulp at my tea, my last birthday suddenly in my head. I’d told Dad I didn’t want him there. Him, or his guilty wad of cash.

When I was three, Dad took me to Disneyworld. Just him and me because Mum had to rest. We ate ice-cream sundaes for breakfast and I was sick twice on the teacup ride. Dad bought me a Mickey Mouse that was bigger than I was. He keeps a snap of me with Mickey in his wallet.

Well, he did. He’s probably stuffed it in a drawer now, made space for a new memory. A new child.

‘I can’t really remember anything from when I was little,’ I say. I put Meg’s photograph back in its place.

Meg gets up, leans round me and pushes the photograph further back, turns it so that it faces into the room.

‘You could remember,’ she says, ‘if you wanted to.’

I flip through the crustacean book again and pretend to drink more tea, even though I’ve drained the mug. My head feels kind of hollow.

‘Where is your dad, then?’ Meg says. ‘Is he coming out to the island too?

‘Look, I didn’t come to – just tell me what you were on about with this “David” thing. I’ve got to go in a minute.’ My voice sounds weird. I cough and clear my throat, pretend the tea went down the wrong way.

‘We’re just having a conversation,’ Meg says. ‘You must’ve had one before. I talk, you talk. We get to know one another. Remember?’

She gets up and peers round the door at her grandad, sits down again.

‘Come on,’ I say. ‘Spill.’

She folds her arms and sits up tall in her seat, just as the blue light above her head fades, flickers and dies. For a second or two we’re in total darkness. Then the sea light recovers and washes over Meg’s face, like a wave.

‘Wind in the power lines,’ she says. ‘Grandad knew there was worse weather on the way. He’s always right.’

‘David,’ I say. This time I’m the one not looking away. Even if the elements are in on Meg’s avoidance tactics. Maybe there is something interesting here . . .

‘Look, it’s no big deal,’ she says quickly. Too quickly. ‘Grandad just gets a bit muddled at times. When he’s tired. He thought you were someone he knew. Old people do that all the time.’ She looks up at the light, like she’s hoping it might do something to get her off the hook.

It doesn’t.

‘Who?’ I say, remembering the urgent bony grip on my arm, the burn of the old man’s eyes back there on the clifftop. The seagull-silencing scream of the evening before. ‘Who did he mistake me for?’

Meg sighs. ‘Sometimes it’s just easier, you know, if I play along for a bit.’ The light flickers again. ‘Like today.’

‘But who’s David?’

Meg stands up. ‘My father,’ she says, her voice like a full stop.

She walks out of the room without looking back.

I follow her back to the living room. The old man is stirring, shifting a little in his chair.

‘I still don’t get it,’ I say, more confused than ever.

‘Grandad needs to eat.’ Meg’s reaching pans down from above her head, clattering them on to the stove. ‘I need to light the fire; in case the power goes off. You should get going. The wind’s getting serious now.’

She crosses to the door, opens it a little, and proves her point. Sand is lifting, spiralling into the air. There’s a threatening howl from the sea.

‘It’ll be dark when the storm really kicks in,’ she says. ‘Storms steal the light out here. Even in the middle of the day. You won’t be able to see a thing – best get going.’

She hands me my coat. I’m going to protest, get more answers, but she’s looking past me. Like one of us has already left.

Cold air slaps my face, and suddenly I’m worrying about Mum and that lunch I promised to make.

‘I’ll be back. Tomorrow,’ I say.

My words are barely out before the door closes and I’m alone, sand in my eyes and nose, wondering how on earth the old man mistook me for a guy three times my age.

And why there had been such desperation in his eyes.

Maybe it’s the meanderings of a tired old mind, like Meg says.

Or maybe those watchful, whispering island kids have a point. Maybe there is something about this island I need to know.

It takes ages to get back to the cottage. The wind does its best to push me back three steps for every two I manage to take.

Mum’s in the kitchen, peeling potatoes over the sink.

I hop on one foot, struggling to prise off my right boot. ‘I’m doing lunch,’ I say. ‘Sit down, Mum, OK?’ I blow on my fingers, try to get the circulation going.

Mum turns, puts down the peeler and reaches for a towel.

She’s been crying. I should have stayed home.

She lifts a smile on to her face, bends down to help with my second boot. When she gets up again, the smile has gone. Like it was too heavy for her to hold.

I’m not hungry any more.

‘We could just have beans on toast?’ I say. ‘And watch a film, maybe?’

‘I went to the shop,’ she says.

This is good. She hasn’t left the house since that trip to the beach. Hasn’t done much of anything.

‘They had a letter for us. For you.’ Her gaze shifts to the table. An envelope is popped up against a jug of artificial flowers. ‘From your dad.’

We both stare at the envelope, like at any minute it might spontaneously combust.

‘Dad doesn’t do letters.’

‘Did he reply to your email, Luke?’

‘Probably wouldn’t know if he had, would I? Like I said, the internet’s rubbish here.’

‘There you are, then.’ Mum picks up the envelope by one corner; holds it out to me. ‘See what he’s got to say.’

I take it, fold it in half. ‘I’ll read it later,’ I say. I shove it into my back pocket. ‘Beans OK, then?’

I can feel the letter all though dinner and a rerun of Liar, Liar – which I chose because it always makes Mum laugh. Tonight it doesn’t. It’s the letter. I know it is. Waiting in my pocket like a threat. Or a promise.

I’m scared of both.

When Mum decides to run a bath, I go to my room, get into bed and stick my headphones in my ears. Jimi Hendrix does his best to drown out the thrash of rain on the window, but he can’t stop Dad’s letter burning my brain from the pile of clothes on the floor.

I rip out the headphones; open it.

There’s only one sheet of paper.

One.

I scan it quickly. I read it again in case I missed something.

I didn’t.

My blood thumps in my ears like Hendrix is still playing.

Dad’s not coming.

He doesn’t care.

I crumple the letter and lob it across the room. It bounces off the strings of my guitar. Dad’s guitar. The red Stratocaster he loved but gave to me because he loved me more.

I told Mum not to bring it here.

I haven’t touched it. It’s just there, propped against the white wall like a scar.

I’m not sure why now, but I pick it up; run my hands over the dusty wood. The neck is thin, delicate. It would snap if I squeezed hard enough. I imagine the sharp, splintering satisfaction of that. I could do it right now if I wanted.

I run the back of one fingernail over the metal strings. They’re badly out of tune, but I start strumming – hard – faster and faster, loving the mess of ugly notes; not stopping when the upper ‘G’ snaps and waves in the air as I play. If you can call it playing. My fingers have softened up. I haven’t played since Dad dropped the baby bombshell and blew a hole through my hopes of him ever coming home. It hurts now: steel on new skin. But I keep on strumming. On and on. Until a second string spikes up and dies.

I’ve got red grooves across my fingertips. A pink scratch on my wrist where the strings fought back. The pain feels pretty good. Stops me thinking. I lie back on the bed, still holding the guitar. I’m drowsy, like I just ran for miles.

Without wanting to I’m remembering. How it used to be: me and the guitar. Drifting, getting lost; saying things I didn’t know I needed to say, with picks, flicks and chord combos.

Feeling things.

Feeling like me.

Dad knows about that. Dad’s been there.

But he’s taken it away from me.

I push the guitar off the bed and kick it, hard, across the floor. It skids against the wardrobe, gives two deep twangs: the last words of an argument. Then it’s staring back at me.

Still. Splintered. Silent.

It’s the saddest thing I’ve ever seen.

When Mum comes in to say goodnight, I pretend to be asleep, so she won’t know I’m upset.

She knows.

Her hand’s on mine. Dad’s letter is a damp ball under her fingers.

‘Luke? What does it say?’

I draw my knees up to my chest, wish I could disappear. Wish Mum would.

‘Sweetheart?’

‘It says Dad’s a loser, OK? Nothing new there.’

I move my hand from hers, pull my pillow over my head. ‘Go to bed, Mum,’ I say, although I don’t think she can hear me.

When I come up for air, the pillow is soaked, the room totally black. I can still smell Mum’s shampoo, but she’s not there any more.