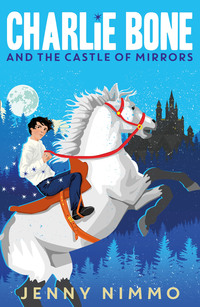

Charlie Bone and the Castle of Mirrors

The photograph showed a fair-haired boy kneeling beside a large yellow dog. Charlie had taken the photo himself, just before Benjamin’s tenth birthday. There was no point in Charlie using his endowment to visit the scene of the photo. It could tell him nothing that he didn’t already know.

In his eagerness to use his strange talent, Charlie often forgot that the people he visited could see him, too. Wherever they were, when Charlie looked at their photos, they would see his face floating somewhere nearby. So Benjamin, who was having a drink in Hong Kong, saw Charlie’s smiling face in his orange juice.

Benjamin took Charlie’s magical appearances in his stride, but Runner Bean, his dog, could never get used to them.

The big dog was about to have his breakfast in the Pets’ Café when Charlie’s face looked up from a bowl of Chappimix.

Runner Bean leapt in the air with a howl; this sent a blue snake slithering under a cupboard and caused a very tall woman called Onoria Onimous to drop a plate of freshly baked scones. But the three colourful cats lying on top of the fridge merely yawned and closed their eyes.

Charlie put the photo in his pocket, shoved the blue cape in his bag and ran downstairs.

‘Don’t forget . . .’ Maisie shouted, but Charlie dashed out of the front door and ran to the top of Filbert Street.

A blue school bus was about to drive off, when the door suddenly opened and a boy with a mop of curly chestnut hair popped his head out. ‘I saw you coming,’ said the boy. ‘The driver said he couldn’t wait but I made him.’

‘Thanks, Fido.’ Charlie handed one of his bags up to his friend, Fidelio, and climbed the steps into the bus.

‘Got your cape?’ asked Fidelio.

Charlie pulled the rumpled garment out of his bag. ‘I hate wearing it when I walk up Filbert Street. People laugh. There’s a boy at number twenty who always shouts, “Here he comes, Little Boy Blue, off to Bloor’s, like a posh cockatoo!” But I didn’t ask to go to Bloor’s, did I?’

‘You’re not a posh cockatoo,’ laughed Fidelio. ‘I bet you forgot to comb your hair again this morning.’

‘I tried.’

The bus had come to a halt and the two boys joined the crowd of children jumping down into a cobbled square. They walked past a fountain of stone swans and approached the steps leading to Bloor’s Academy.

As Charlie walked into the shadow of the music tower, he found himself looking up at the steep roof of the turret. It had become a habit of his and he scarcely knew why he did it. Once, his mother had told him she felt someone watching her from the small window under the eaves. Charlie gave an involuntary shiver and followed Fidelio through the wide arched entrance.

Surrounded by children in capes of blue, purple and green, Charlie looked for Emma Tolly and Olivia Vertigo. He saw Emma in her green cape, her long blonde hair in two neat plaits, but he was momentarily baffled by the girl beside her. He knew the face but . . . could it be Olivia? She was wearing a purple cape, like everyone else in Drama, but Olivia’s face was usually covered in make-up, and she always dyed her hair a vivid colour. This girl had a scrubbed look: rosy cheeks, grey eyes and short brown hair.

‘Stop staring, Charlie Bone,’ said the brown-haired girl, walking up to him.

‘Olivia?’ Charlie exclaimed. ‘What happened?’

‘I’m auditioning for a part in a movie,’ Olivia told him. ‘Got to look younger than I really am.’

They climbed another set of stone steps, and then they were walking between two huge doors studded with bronze figures. As soon as all the children were safely inside, Weedon, the porter and handyman, closed and locked the doors. They would remain locked until Friday afternoon, when the children were allowed home for the weekend.

Charlie stepped into the vast stone-flagged hall of Bloor’s Academy. ‘What’s the movie?’ he asked Olivia.

‘Sssh!’ hissed a voice from somewhere near Charlie’s ear.

Charlie looked up into a pair of coal-black eyes and nearly jumped out of his skin. He thought Manfred Bloor had left the school.

‘I hope you haven’t forgotten the rules, Charlie Bone!’ barked Manfred.

‘N. . . no, Manfred.’ Charlie didn’t sound too sure.

‘Come on then . . .’ Manfred clicked his fingers and glared at Charlie who looked down at his feet. He didn’t feel like fighting Manfred’s hypnotising stare so early in the day.

‘Come on, what are the rules?’ Manfred demanded.

‘Erm . . .

Silence in the hall,

Talking not at all,

Never cry or call,

Even if you fall,

‘Erm . . .’ Charlie couldn’t remember the last line.

‘Write it out a hundred times and bring it to my study after tea!’ Manfred grinned maliciously.

Charlie didn’t know Manfred had a study, but he had no intention of prolonging the conversation. ‘Yes, Manfred,’ he mumbled.

‘You should be ashamed of yourself. You’re in the second year now. Not a very good example for first-formers are you, Charlie Bone?’

‘Nope.’ Charlie caught sight of Olivia, rolling her eyes at him, and only just managed to stop himself from giggling. Luckily Manfred had spotted someone without a cape and strode away.

Olivia had disappeared into a sea of purple capes whose owners were crowding through a door beneath two bronze masks. Beyond the open door Charlie glimpsed the colourful mess that was already building up inside the purple cloakroom. He hurried on to the sign of two crossed trumpets.

Fidelio was waiting for him just inside the blue cloakroom. ‘Whew! What a shock!’ breathed Fidelio. ‘I thought Manfred had left.’

‘Me too,’ said Charlie. ‘That was the one good thing about coming back to Bloor’s. I thought at least Manfred wouldn’t be here.’

What was Manfred’s new role? Would he be permanently on their tails, watching, listening and hypnotising?

The two boys discussed the problem of Manfred as they walked to Assembly. On the first day of every school year, Assembly was held in the theatre, the only space large enough for all three hundred pupils. Charlie hadn’t joined Bloor’s Academy until the middle of the last autumn term; it was a new experience for him.

‘Yikes! I’d better hurry,’ said Fidelio, looking at his watch. ‘I should be tuning up.’

Dr Saltweather, head of Music, gave Fidelio a severe nod as he climbed up to the stage and took his place in the orchestra. Charlie joined the end of the second row, and found himself standing directly behind Billy Raven. The small albino turned round with a worried frown.

‘I’ve got to stay in the first year for another twelve months,’ he whispered to Charlie, ‘but I’ve already done it twice.’

‘Bad luck! But you are only eight.’ Charlie scanned the row of new children in front of him. They all looked fairly normal, but you could never tell. Some of them might be endowed like himself and Billy; children of the Red King.

For the rest of the morning, Charlie tramped around the huge, draughty building, finding his new classroom, collecting books and looking for Mr Paltry (who was supposed to be giving him a trumpet lesson).

By the time the horn sounded for lunch, Charlie was utterly exhausted. He slouched down to the canteens, averting his eyes from the portraits that hung in the dimly lit corridor – just in case one of them wanted a conversation – and arrived at the blue canteen.

Charlie joined the queue. A small, stout woman behind the counter gave him a wink. ‘All’s well then, Charlie?’ she asked.

‘Yes, thanks, Cook,’ said Charlie. ‘But it’ll take me a while to get used to the second year.’

‘It will,’ said Cook. ‘But you know where I am, if you need me. Peas, Charlie?’

Charlie accepted a plate of macaroni cheese and peas and wandered round the tables until he found Fidelio, sitting with Billy Raven and Gabriel Silk. Gabriel’s floppy brown hair almost obscured his face, and there was a forlorn droop to his mouth.

‘What’s up, Gabe?’ asked Charlie. ‘Are your gerbils OK?’

Gabriel looked up sadly. ‘I can’t do piano this term. Mr Pilgrim’s gone.’

‘Gone?’ Charlie was unexpectedly dismayed. ‘Why? Where?’

Gabriel shrugged. ‘I know Mr Pilgrim was peculiar, but, well, he was just – brilliant.’

No one could deny this. Mr Pilgrim’s piano playing was often to be heard echoing down the Music Tower. Charlie realised he would miss it. And he would miss seeing Mr Pilgrim staring into space, his black hair always falling into his eyes.

Fidelio turned to Billy. ‘So how was your holiday, Billy?’ he asked carefully. For how could anyone spend their whole holiday in Bloor’s Academy without going mad?

‘Better than usual,’ said Billy cheerfully. ‘Cook looked after Rembrandt like she promised, and I saw him every day. And Manfred went away for a bit and so it was OK here, really, except . . . except . . .’ a shadow crossed his face, ‘something happened last night. Something really weird.’

‘What?’ asked the other three.

‘I saw a horse in the sky.’

‘A horse?’ Fidelio raised his eyebrows. ‘D’you mean a cloud that looked like a horse?’

‘No. It was definitely a horse.’ Billy took off his glasses and wiped them on his sleeve. His deep red eyes fixed themselves on Charlie. ‘It sort of hung there, outside the window, and then it just faded.’

‘Stars can do that,’ said Gabriel, who had perked up a bit. ‘They can create the illusion of animals and things.’

Billy shook his head. ‘No! It was a horse.’ He replaced his glasses and frowned at his plate. ‘It wasn’t far away. It was right outside the window. It reared up and kicked the air, like it was fighting to be free, and then it just – faded.’

Charlie found himself saying, ‘As if it was receding into another world.’

‘That’s right,’ said Billy eagerly. ‘You believe me, don’t you, Charlie?’

Charlie nodded slowly. ‘I wonder where it is now?’

‘Wandering round the castle ruin with all the other ghosts?’ Fidelio wryly remarked. ‘Come on, let’s get some fresh air. We might see a horse galloping round the garden.’

Of course he was only joking but, as soon as the four boys walked through the garden door, Fidelio realised that his words held a ghostly ring of truth. He was the only one of the four who was not endowed. Fidelio might be a brilliant musician, but his endowment was not one that could be classed as magical.

It was Charlie who noticed it first: a faint thudding on the dry grass. He looked at Gabriel. ‘Can you hear it?’

Gabriel shook his head. He could hear nothing, but there was a presence in the air that he couldn’t define.

Billy was the most affected. He stepped back suddenly, his white hair lifting in a breeze that no one else could feel. He put up his hand as if to ward off a blow. ‘It went right past,’ he whispered.

Fidelio said, ‘You’re having me on, aren’t you?’

‘’Fraid we’re not,’ said Charlie. ‘It’s gone now. Maybe it just wanted us to know it was here.’

They began to cross the wide expanse of grass that Dr Bloor liked to called his garden. It was really no more than a field, bordered by near-impenetrable woods. At the end of the field the red stones of an ancient castle could be glimpsed between the trees: the castle of the Red King. The four boys almost instinctively made their way towards the tall red walls.

Charlie’s Uncle Paton had told him how, when Queen Berenice died, five of the Red King’s children had been forced to leave their father’s kingdom forever. Brokenhearted, the king had vanished into the forests of the north and Borlath, his eldest son, had taken the castle. He had ruled the kingdom with such barbarous cruelty most of the inhabitants had either died or fled in terror.

‘Well?’ said Fidelio. ‘D’you think the phantom horse is here?’

Charlie looked up at the massive walls. ‘I don’t know.’ He looked at Billy.

‘Yes,’ he whispered. ‘It’s here.’

The others listened intently. They could hear the distant shouts and chatter of children on the field, the thump of a football, the call of wood pigeons, but nothing else.

‘Are you sure, Billy?’ asked Charlie.

Billy hugged himself. He was shivering. ‘I think it would like to speak, but it’s caught on the wrong side.’

‘Wrong side of what?’ asked Fidelio.

Billy frowned. ‘I can’t explain.’

Charlie became aware that someone was standing behind them. He turned round, just in time to see a small figure dart away and join a group of new boys, playing football together.

‘Who was that?’ asked Gabriel.

‘New boy,’ said Charlie.

It was impossible to tell whether the boy was in Art, Drama or Music because he wasn’t wearing a cape. Today, it was warm and sunny. Summer was not yet over.

The sound of the horn rang out across the field and the four boys ran back into school.

For Charlie, the afternoon was no better than the morning. He found Mr Paltry at last, but too late for his lesson. ‘What’s the point of coming to a lesson without your trumpet?’ grumbled the elderly teacher. ‘You’re a waste of time, Charlie Bone. Endowed, my foot. Why don’t you use your so-called talent to locate your trumpet? Now get out and don’t come back until you’ve found it.’

Charlie left quickly. He had no idea where to look. ‘The Music Tower?’ Charlie asked himself. Perhaps one of the cleaners had found his trumpet and put it in Mr Pilgrim’s room at the top of the tower.

The way to the Music Tower led through a small, ancient-looking door close to the garden exit. Charlie braced himself, opened the door and began to walk down a long, damp passage. It was so dark he could barely see his own feet. He kept his eyes on a distant window in the small circular room at the end of the passage.

As he got closer to the room he began to hear voices, angry voices; men arguing.

There was a clatter of footsteps. Charlie stood still until whoever it was had reached the bottom of the long, spiralling staircase. A figure appeared at the end of the passage. It loomed towards Charlie and raised its purple wings, blocking out the light.

Plunged in darkness, Charlie screamed.

The boy with paper in his hair

‘Quiet!’ hissed a voice.

Charlie shrank against the wall as the person, or thing, swept past and whisked itself through the door into the hall.

Charlie didn’t know what to do. Should he go back the way he had come, or on towards the tower? The hissing person might be in the hall, waiting for him. He chose the tower.

As soon as he emerged in the round sunlit room at the end of the passage, Charlie felt better. Those purple wings had been the arms of a cape, he reasoned. And the angry person was probably a member of staff, arguing with someone. He began the long, spiral ascent to the top of the tower. Bloor’s Academy had five floors, but Mr Pilgrim’s music room was up yet another flight.

Charlie reached the small landing where music books were stored on shelves, in boxes and in untidy piles on the floor. Between the rows of shelving a small oak door led into the music room. A message had been pinned to the centre of the door. Mr Pilgrim is away.

Charlie rummaged in the boxes, lifted the piles of music and searched behind the heavy books on the shelves. He found a flute, a handful of violin strings, a tin of oatcakes and a comb, but no trumpet.

Was there any point in trying the room next door? Charlie remembered seeing a grand piano and a stool, nothing else. He looked again at the note. Mr Pilgrim is away. It looked forbidding, as though there was another message behind those four thinly printed words: Do not enter, you are not welcome here.

But Charlie was a boy who often couldn’t stop himself from doing what all the signs told him not to. This time, however, he did knock on the door before going in. To his surprise, he got an answer.

‘Yes,’ said a weary voice.

Charlie went in.

Dr Saltweather was sitting on the music stool. His arms were folded inside his blue cape and his thick, white hair stood up in an untidy, careless way. He wore an expression that Charlie had never seen on his face before: a look of worry and dismay.

‘Excuse me, sir,’ said Charlie. ‘I was looking for my trumpet.’

‘Indeed.’ Dr Saltweather glanced at Charlie.

‘I suppose it isn’t in here.’

‘Nothing is in here,’ said Dr Saltweather.

‘Sorry, sir.’ Charlie was about to go when something made him ask, ‘Where is Mr Pilgrim, sir?’

‘Where?’ Dr Saltweather looked at Charlie as if he’d only just seen him. ‘Ah, Charlie Bone.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘I don’t know where Mr Pilgrim has gone. It’s a mystery.’

‘Oh.’ Charlie was about to turn away again but this time found himself saying, ‘I bumped into someone in the passage; I thought it might be him.’

‘No, Charlie.’ The music teacher spoke with some force. ‘That would have been Mr Ebony, your new form teacher.’

‘Our form teacher?’ Charlie gulped. He thought of the purple wings, the hissing voice.

‘Yes. It’s a little worrying, to say the least.’ Dr Saltweather gave Charlie a scrutinising stare, as though wondering if he should say more. ‘Mr Ebony came here to teach history,’ he went on, ‘but he turned up with a letter of resignation from Mr Pilgrim. I don’t know how he came by it. And now this – man – wants to teach piano.’ Dr Saltweather raised his voice. ‘He comes up here, puts a message on the door, tries to keep me out of a room in my own department . . . it’s intolerable!’

‘Yes, sir,’ agreed Charlie. ‘But he was wearing a purple cape, sir.’

‘Ah, yes, that!’ Dr Saltweather ran a hand through his white hair. ‘It seems that Mr Tantalus Ebony is in the Drama department, hence the purple.’

Charlie said, ‘I see,’ although, by now, he was very confused. He had never heard of a teacher being in three departments at once.

‘They are Dr Bloor’s arrangements, so what can I do?’ Dr Saltweather spread his hands. ‘Better run along now, Charlie. Sorry about the trumpet. Try one of the Art rooms. They’re always drawing our musical instruments.’

‘Art. Thank you, sir,’ said Charlie gratefully.

The Art rooms could only be reached by climbing the main staircase and Charlie had just put his foot on the first step when Manfred Bloor came out of a door in the hall.

‘Have you finished writing out your lines?’ asked Manfred coldly.

‘Er, no.’

Manfred approached Charlie. ‘Don’t forget, or you’ll get another hundred.’

‘Yes, Manfred. I mean no.’

Manfred gave a sigh of irritation and walked away.

‘Excuse me,’ Charlie said suddenly, ‘but are you still, erm, a pupil, Manfred?’

‘No I am not!’ barked the surly young man. ‘I am a teaching assistant. And call me sir.’

‘Yes, sir.’ The word ‘sir’ tasted funny when applied to Manfred, but Charlie smiled, hoping he’d said the right thing at last.

‘And don’t forget it.’ Manfred marched back into the Prefects’ room and slammed the door.

Charlie still hadn’t found Manfred’s study. He was now torn between looking for his trumpet and writing out a hundred lines. But then he remembered that he didn’t know the last line of the Hall rules. ‘Emma will tell me,’ he said to himself, and he began to climb the stairs.

Emma was often to be found in the Art gallery, a long, airy room overlooking the garden. Today, however, the room appeared to be empty. Charlie searched the paint cupboard and inspected the shelves at the back of the room, then he crossed the gallery and descended an iron spiral that took him down into the sculpture studio.

‘Hi, Charlie!’ called a voice.

‘Hey, come on over,’ called another.

Charlie looked round to see two boys in green aprons grinning at him from either side of a large block of stone. One had a brown face and the other was very pale. Charlie’s two friends were now in the third year. They had both grown considerably during the summer holiday, and so had their hair. Lysander, the African, now had a neat head of dreadlocks decorated with coloured beads, while Tancred had gelled his stiff, blond hair into a forest of spikes.

‘What brings you down here, Charlie?’ asked Tancred.

‘I’m looking for my trumpet. Hey, I hardly recognised you two.’

‘You haven’t changed,’ said Lysander with a wide smile. ‘How d’you like the second year?’

‘I don’t know. I’m in a bit of a muddle. I keep going to the wrong place. I’ve lost my trumpet. I’m in trouble with Manfred and there’s an er, um, thing in the garden.’

‘What d’you mean, a thing?’ Tancred’s blond hair fizzled slightly.

Charlie told them about the horse Billy had seen in the sky, and the hoofbeats in the garden.

‘Interesting,’ said Lysander.

‘Ominous,’ said Tancred. ‘I don’t like the sound of it.’ The sleeves of his shirt quivered. It was difficult for Tancred to hide his endowment. He was like a walking weathervane, his moods affecting the air around him to such an extent that you could say he had his own personal weather.

‘I’d better keep looking for my trumpet,’ said Charlie. ‘Oh, what’s the last line of the Hall rules?’

‘Be you small or tall,’ said Lysander quickly.

‘Thanks, Sander. I’ve got to write the whole thing out a hundred times before supper, and give it to Manfred – if I can find his study. You don’t happen to know where it is, do you?’

Tancred shook his head and Lysander said, ‘Not a clue.’

Charlie was about to return the way he’d come when Tancred suggested he try somewhere else. ‘Through there,’ said Tancred, indicating a door at the end of the Sculpture studio. ‘The new children are having their first art lesson. I think I saw one carrying a trumpet.

‘Thanks, Tanc!’

Charlie walked into a room he’d never seen before. About fifteen silent children sat round a long table, sketching. Each of them had a large sheet of paper and an object in front of them. They were all concentrating fiercely on their work, and none of them looked up when Charlie appeared.

‘What do you want?’ A thin, fair-haired man with freckles spoke from the end of the table. A new Art teacher, Charlie presumed.

‘My trumpet, sir,’ said Charlie.

‘And why do you think it’s here?’ asked the teacher.

‘Because, there it is!’ Charlie had just seen a trumpet exactly like his. The instrument was being sketched by a small boy with bits of paper sticking to his hair. The boy looked up at Charlie.

‘Joshua Tilpin,’ said the teacher, ‘where did you get that trumpet?’

‘It’s mine, Mr Delf.’ Joshua Tilpin had small pale grey eyes. He half-closed them and wrinkled his nose at Charlie.

Charlie couldn’t stop himself. He leapt forward, seized the trumpet and turned it over. Last term he had scratched a tiny CB near the mouthpiece. The trumpet was his. ‘It’s got my initials on it, sir.’

‘Let me see.’ Mr Delf held out his hand.

Charlie handed over the trumpet. ‘My name’s Charlie Bone, sir. See, they’re my initials.’

‘You shouldn’t deface musical instruments like this. But it does appear to be yours. Joshua Tilpin, why did you lie?’

Everyone looked at Joshua. He didn’t go red, as Charlie would have expected. Instead, he gave a huge grin, revealing a row of small, uneven teeth. ‘Sorry, sir. Really, really sorry, Charlie. Only a joke. Forgive me, please!’

Neither Charlie nor the teacher knew how to reply to this. Mr Delf passed the trumpet to Charlie, saying, ‘You’d better get back to your class.’

‘Thank you, sir.’ Charlie clutched his trumpet and turned to the door. He took a good look at Joshua Tilpin as he went. He had an odd feeling that the new boy was endowed. Joshua’s sleeves were covered in scraps of paper and tiny bits of eraser. Even as Charlie watched, a broken pencil lead suddenly leapt off the table and attached itself to the boy’s thumb. He gave Charlie a sly grin and flicked it off. Charlie felt as though an invisible thread were tugging him towards the strange boy.