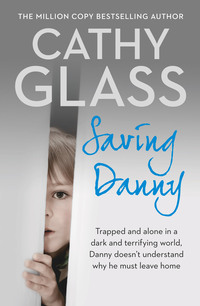

Saving Danny

As the children finished eating they left the table one at a time to go upstairs and carry on getting ready for school. I waited with Danny while he emptied his bowl of cornflakes and then drank his glass of milk.

‘Good boy,’ I said. ‘Now it’s time for you to go upstairs so you can wash and brush your teeth.’

‘George?’ he asked questioningly, glancing towards the back door.

‘Do you feed George in the morning?’ I asked.

He nodded.

‘Your mummy will feed George today,’ I said. ‘I’ll talk to her about George when I see her this morning at school.’

He accepted this, slid from his chair and then followed me down the hall and upstairs. In the bathroom he completed the tasks of washing and brushing his teeth in the same order and with the same precision as he had the previous evening.

Adrian, Lucy and Paula left for their respective secondary schools, calling goodbye as they went. Then, once Danny had finished in the bathroom, we went downstairs, where I told him we needed to put on our shoes and coats ready to go to school. I went to unhook his coat from the stand, but he put his hand on my arm to stop me. ‘Of course,’ I said, smiling. ‘You want to do it yourself.’

I lifted him up and he unhooked his coat, then struggled into it, finally accepting my help to engage the zipper. He sat on the floor to put on his shoes, and when he’d finished I praised him. He put so much effort into everything he did, it was important he knew when he’d done well. He didn’t have a school bag; I assumed it had been left at school.

‘We’re going outside, so hold my hand, please,’ I said as I opened the front door.

He did as I asked and we went to my car on the driveway. I opened the rear door and Danny clambered into the child seat and then fastened his own seatbelt. I checked it was secure, closed his door and went round and climbed into the driver’s seat. As I drove I reminded Danny what was going to happen that day (as far as I knew); that we were going to school where he would see his mother, and I was going into a meeting. Then at the end of the day I would collect him from school and bring him home with me. I didn’t mention that Jill was visiting us at 4 p.m., as I thought it might overload him with information; I’d tell him after school. He didn’t reply, but I knew he was taking it all in – his gaze was fixed and serious as he concentrated.

Although I was slightly anxious about meeting his mother for the first time, I was also looking forward to it. I would learn more about Danny, and hopefully I’d be able to work with his parents with the aim of eventually returning Danny home. Having looked after Danny for only one night, I appreciated how his parents might have struggled. Caring for Danny was hard work, and I’d had plenty of experience looking after children – many with special needs. Some parents are very angry when their child or children first go into care, although given that Danny had been placed in care voluntarily I didn’t think that was likely. I thought his parents would probably be upset rather than angry, and I was right – although I was completely unprepared for just how upset Danny’s mother would be.

Chapter Five

Absolute Hell

The school building and surrounding trees and shrubbery seemed a lot more welcoming now it was light than it had the evening before in darkness. Some parents were already in the playground chatting to each other while their children played before the start of lessons. I was planning on going straight into school with Danny that morning as the meeting started at nine o’clock, but as we entered the playground I heard Danny’s name being called. I turned and saw a woman rushing towards us in tears. I guessed it was Danny’s mother, Reva. She scooped him up and, holding him to her, buried her head in his shoulder and sobbed.

‘Shall we go inside?’ I suggested, touching her arm reassuringly. ‘It’ll be more private.’ I could see others in the playground looking and I felt Danny’s reunion with his mother – and her grief – needed some privacy.

‘Yes, please,’ Reva said quietly.

She carried Danny and we walked towards the main door. As we approached, it opened from inside and Sue Bright, Danny’s teacher, came out. ‘I’ve been looking out for you,’ she said. ‘Come in. We can use the medical room, it’s free.’

‘Thank you,’ I said.

We followed Sue down a short corridor, turned left and entered the medical room, which was equipped with a couch, three chairs, a sink and a first-aid cupboard. Danny’s mother sat on one of the chairs and held Danny on her lap, close to her. ‘He must have missed me so much,’ she said through her tears. ‘He never normally lets me touch him.’

Danny said one word in a flat and emotionless voice: ‘Mum.’

‘Would you like some time alone?’ Sue asked Reva.

‘Yes, please,’ she said.

‘We’ll come back in a few minutes when school starts,’ Sue added.

I left the medical room with Sue and she closed the door behind us. ‘Has he been very upset?’ she asked me, concerned.

‘More quiet and withdrawn, really,’ I said. ‘But he slept well, and has been eating.’

Sue nodded. ‘Danny is often withdrawn in school; that’s one of his problems.’

‘Has there been an assessment?’ I asked.

‘Not yet.’ She paused. ‘Would you mind waiting until the meeting to talk about this? It’s complicated and I need to see to my class soon.’

‘That’s fine, of course,’ I said.

‘Thanks. His social worker, Terri, is on her way. She’ll be about five minutes. Once school starts Danny can join his class, and then we can have our meeting. We’ll use the staff room. It’ll be empty once school begins. We’re only a small school and a bit short of space. Are you all right to wait here while I bring my class in from the playground?’

‘Yes, go ahead.’

‘I’ll be about ten minutes.’

Sue disappeared around the corner and I waited in the small corridor outside the medical room. While I waited I looked at the children’s art work that adorned most of every wall. Although it was only a small school it came across as being very friendly and child-centred. Danny’s teacher, Sue, seemed really kind and caring, as had the other staff I’d briefly met the evening before. My thoughts went to Danny’s mother, Reva, who unlike Danny was quite tall, but also slender. She was in her late thirties and was dressed smartly in a grey skirt and matching jacket. I felt sorry for her. She was so upset; she and her husband must have had a sleepless night, counting the hours until they could see Danny again. Her husband wasn’t with her, but Terri had said there was going to be regular contact, so he would see Danny before too long.

A whistle sounded in the playground signalling the start of school, and presently I heard the clamour of children’s voices as they filed into the building and went to their classrooms. Then Sam, the caretaker I’d briefly met the evening before, appeared at the end of the corridor. ‘How’s the little fellow doing?’ he asked cheerfully.

‘He’s doing all right,’ I smiled.

‘Good for you. You foster carers do a fantastic job. I know – I was brought up in care.’ And with a nod and a smile he went off to go about his duties. That was a nice comment, I thought.

Five minutes later the school was quiet as the first lesson began. Sue appeared with Terri and we said good morning. ‘How’s Danny been?’ Terri asked.

‘Quiet,’ I said. ‘But he ate and slept well, and we only had one tantrum.’

‘Good. Have you met his mother, Reva?’

‘Just briefly in the playground. She’s very upset.’

Terri nodded. ‘Shall we get started then? I have to be away by ten-thirty as I have another meeting at eleven.’

Sue knocked on the door to the medical room and she and Terri went in, while I waited at the door. I could see Danny was now sitting on a chair beside his mother. They both had their hands in their laps, and were quiet and still.

‘Danny, I’ll take you to your class now,’ Sue said gently.

Danny obediently stood.

‘Say goodbye to your mother,’ Sue said.

‘Goodbye,’ Danny said in a small, flat voice and without looking at her.

‘Goodbye, love,’ she called after him. ‘I’ll see you later.’

Danny didn’t reply or show any emotion but walked quietly away with his teacher.

‘Will you show Reva and Cathy to the staff room?’ Sue said to Terri. ‘I’ll join you there once I’ve taken Danny to his class.’

‘Bye, love,’ Danny’s mother called again as he left, but Danny didn’t reply.

‘How are you?’ Terri now asked Reva as she stood, looping her handbag over her shoulder.

She shrugged and dabbed her eyes with a tissue.

‘You’ve met Cathy,’ Terri said to her.

She nodded, tears glistening in her eyes.

‘Hello, Reva,’ I said with a smile.

I could see the family resemblance between her and Danny – the same mouth and eyes.

‘I did my best for him,’ she said as we left the medical room. ‘Really I did, but I’ve failed.’ Her tears fell.

‘You haven’t failed,’ I said. ‘Danny is a lovely boy, but I can appreciate just how much it takes to look after him.’

‘You don’t blame me then?’ she said, slightly surprised.

‘No, of course not.’

‘No one blames you,’ Terri added. ‘I’ve told you that.’

‘My husband does,’ Reva said.

‘For what?’ Terri asked.

‘Having an autistic son.’

Reva and I went with Terri to the staff room where we settled around the small table that sat at one end of the room and waited for Sue. The staff room was compact, with pigeonhole shelving overflowing with books and papers, and pin boards on the walls covered with notices, leaflets and flyers. On a cabinet stood a kettle beside a tray containing mugs and a jar of coffee. But like the rest of the school the staff room emanated a cosy, warm feeling, easily making up for what it lacked in size. Reva, sitting opposite me, had dried her eyes now, but I could see she wasn’t far from tears. Terri, to her right, had taken out a notepad and was writing. I felt I needed to say something positive to Reva to try to reassure her.

‘Danny did very well last night,’ I said. ‘Our house was obviously all new to him, but he coped well. He ate dinner with us and then played with some Lego.’

‘Terri said it took ages to find him on the playing field,’ Reva said despondently. ‘Danny’s good at running off and hiding. You’ll need to be careful.’

‘I’ll remember that,’ I said. Although I’d rather guessed that might be the case.

‘You’ll have to lock all your doors and windows or he’ll run off outside and you’ll never find him,’ Reva said.

‘Don’t worry,’ I reassured her. ‘My house is secure. He’ll be safe.’ Foster carers are not allowed to lock children in the house even for their own safety, but I knew that Danny couldn’t reach to open the front and back doors, and I would be keeping a close eye on him. ‘I like his method of dressing,’ I said to Reva, again focusing on the positive. ‘Did you and your husband teach him to do that?’

‘I did,’ Reva said softly.

Terri looked at us questioningly and I explained how Danny had laid out his clothes in the order he should put them on.

‘Very good,’ Terri said. ‘Does that work for him at school too – after games?’ she asked.

‘I think his classroom assistant helps him,’ Reva said.

The door opened and Sue came in carrying a file. ‘Sorry to keep you,’ she said. ‘Danny is with his class now.’ She smiled at Reva as she sat next to me.

‘Are we expecting anyone else?’ Terri asked.

‘My support social worker can’t make it,’ I said. ‘I’m seeing her later so I’ll update her then.’

‘Is Danny’s father joining us?’ Terri now asked Reva.

‘No,’ she said, but she didn’t add why.

‘Let’s get started then,’ Terri said. ‘I thought this meeting would give us a chance to discuss how we can best help Danny. The three of us and his father are the key people in Danny’s life right now. I’ll make a few notes as we go, but I want to keep this meeting informal. I’m in the process of drawing up a care plan, and as a child in care Danny will have regular reviews.’ She glanced at Reva. ‘We’ll talk about contact arrangements later. Cathy, as Reva didn’t have a chance to meet you before Danny came to you, perhaps you’d like to start by telling her a little about your family and home life?’

‘Yes, certainly,’ I said. I sat slightly forward and looked at Reva as I spoke. ‘I have three children – a boy, fifteen, and two girls, thirteen and eleven, and a cat, Toscha. She doesn’t bite or scratch. I’m divorced and have been fostering for over fifteen years now. I live in …’ I briefly described my house and then my family’s routine, and the types of things we liked to do at the weekends. ‘Danny will, of course, be included in all family activities and outings,’ I said. ‘Whether it’s a visit to a local park or to see my parents. Danny’s bedroom is at the rear of the house and overlooks the garden, so it is quiet and has a nice view. He’ll be able to play in the garden when the weather is good. Last night before Danny went to bed I showed him where my bedroom was in case he needed me in the night, but he slept through. It was a good idea packing his toy rabbit, George,’ I concluded positively, smiling at Reva. ‘That helped him to settle.’

‘Did he ask for the real George?’ Reva asked.

‘Yes. I had to show him he wasn’t outside.’

Terri looked at us, puzzled.

‘George is Danny’s pet rabbit,’ Reva said to Terri. ‘They’re inseparable. I did tell Danny he couldn’t take him to Cathy’s. I think that was one of the reasons he kicked me and ran off and hid yesterday.’

I looked at Terri. ‘I know it’s not usual fostering practice,’ I said, ‘but I was thinking that if Reva and her husband agreed then perhaps George could come and stay with us too? He means so much to Danny. It could help him settle.’

‘Oh, would you?’ Reva cried. ‘I’d be so grateful. Danny loves his rabbit more than anything – probably more than he loves me.’

‘Are you sure that’s all right?’ Terri asked me.

‘Yes. I don’t mind pets, and George lives in his hutch outside.’

‘Danny likes to bring him into the house sometimes,’ Reva said. ‘But he doesn’t make much mess.’

‘I’m sure it will be fine,’ I said.

‘If it doesn’t work out you can always return it to Reva,’ Terri said.

I met Reva’s gaze and we both knew that wasn’t an option. It would be devastating for a child like Danny to be allowed to have his beloved pet stay and then have to return him home while he remained in care. He wouldn’t cope.

‘It’ll be fine,’ I said again.

‘Well, if you’re sure,’ Terri said. ‘I’ll leave the two of you to make arrangements at the end of this meeting to collect George.’

‘Thank you,’ Reva said to me.

I thought the meeting had got off to a good start and that George was now one less thing for Reva to worry about, but then her face clouded and she began to cry.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said, taking a fresh tissue from her handbag. ‘You’re all being so nice to me and trying to help. I really don’t deserve it.’

‘Of course you deserve it,’ Terri said. ‘We all want to help you and Danny. You must stop blaming yourself. It’s not your fault Danny is as he is.’ Then to Sue, Terri said, ‘Would you like to tell us a bit about how Danny is doing in school? I expect Cathy will want to help him with his homework.’

‘We don’t actually set Danny homework as such,’ she said. ‘More targets to work towards, in line with his individual education plan. Reva has a copy of the plan and I can have one printed for Cathy, if that’s all right with Reva?’

Reva nodded.

Sue made a note of this and then said, ‘Danny has been in this school a year. He arrived after his parents moved into the area with his father’s job. At present Danny is working towards a reception-level standard. He is difficult to assess educationally because of his communication difficulties, but he is about two to three years behind his peer group. He tries his best but finds the core subjects of English, maths and science very challenging, although I adapt all the work to suit his needs. He does like art, especially drawing, painting and creating patterns. He’s very good at making patterns. Danny has communication and language difficulties – both receptive and expressive – so we have to pace his learning to fit him. His teaching assistant, Yvonne, is good with him and has endless patience. Danny is uncoordinated and finds games lessons difficult, but he likes a good run around the playing field.’

‘Yes, I noticed that last night,’ Terri said dryly.

I smiled.

‘Tell them about his meltdowns,’ Reva now said.

Sue looked at me. ‘Danny can become frustrated when he is unable to express himself or there is too much going on for him, and he has a “meltdown”. Yvonne and I have become adept at spotting the warning signs and can sometimes distract him to avoid it, but not always. He’ll lie on the floor, scream and shout and lash out at anyone who goes near him. It’s very upsetting for him, and for us to witness.’

‘He does it at home as well,’ Reva said. ‘And in public, in the street and in shops. Everyone stares. I know they blame me for not controlling him properly, but I don’t know what to do.’ She was close to tears again.

‘As an experienced and specialist foster carer you’ll be able to cope with Danny’s behaviour, won’t you?’ Terri said to me.

‘Yes,’ I said confidently, although I was feeling far from confident inside.

‘Danny finds it difficult to make friends,’ Sue continued. ‘The children in the class are very tolerant of him and kind, but he doesn’t have a proper friend. He doesn’t understand how to make friends, although Yvonne has tried to show him. In the playground he keeps close to her or one of the other assistants. He can easily become overwhelmed by all the noise and activity, so we often bring him in early. He eats his lunch with the other children in the dining hall, but he takes a long time and is usually the last to finish.’ My heart clenched as I imagined little Danny sitting all alone in a big dining room while the other children were outside playing. ‘Yvonne or one of the other assistants stays with him until he’s finished,’ Sue said. ‘There are a lot of unknowns with Danny and at times he’s very difficult to reach. The school would like the educational psychologist to assess him so that we’re all in a better position to help him meet his full potential. But we need the parents’ permission for that assessment.’

Which begged the question: why hadn’t his parents given permission?

Terri turned to Reva. ‘Is your husband still not happy with Danny being assessed?’

‘He won’t,’ Reva said. ‘He is ashamed. He refuses to admit anything is wrong with Danny.’

‘I’ll have a chat with him and explain why it’s important Danny is assessed,’ Terri said, making a note. Then looking at Sue she said, ‘Is that everything for now?’

‘I think so.’

‘Thank you,’ Terri said. Then she turned to Reva: ‘Would you like to say a bit about Danny? Perhaps tell Cathy about his likes and dislikes, and his routine. Anything you think may help her look after Danny.’

‘Yes,’ Reva said. ‘I’ve made a few notes.’ She unhooked her shoulder bag from the back of her chair and, opening it, slid out a thick wodge of papers. ‘This is Danny’s daily routine,’ she said, passing it across the table to me. ‘It never alters.’

‘Thank you,’ I said, taking it. I began flipping through. Usually a parent will say a few words about their child’s routine, very occasionally they’ll give me some notes, but never in all my years of fostering had I seen anything this detailed before: twenty-three pages of A4 paper covered in small print.

‘Perhaps you could read it later,’ Terri said, aware of the volume of paperwork.

I nodded and smiled at Reva. ‘Thank you. This will be helpful.’

‘Is there anything you want to add to what you’ve written?’ Terri asked Reva.

I assumed there wouldn’t be, given the detail in the paperwork, but Reva said, ‘Yes. That’s just Danny’s routine. Cathy also needs to know what it’s like looking after Danny. I mean, what it’s really like.’ She paused, and I saw her bottom lip tremble. ‘It’s been hell,’ she said. ‘Absolute hell. It’s a nightmare looking after Danny. I know it’s my fault, and some days I wish he’d never been born.’ Her face crumpled into tears.

Chapter Six

Prisoners

My heart went out to Reva. She was clearly carrying a huge burden of guilt and self-blame for Danny’s problems, and appeared to be at her wits’ end, and close to breaking point. Terri, Sue and I tried to reassure her, but her feelings of inadequacy were too deeply ingrained, and I wondered how much of this was a result of her husband’s attitude. Reva’s previous comment about him blaming her for having an autistic son weighed heavily in my thoughts. The last thing the poor woman needed was to be blamed by her partner; she needed all the help and support she could get.

Presently Reva dried her eyes and was composed enough to continue. ‘Danny cried a lot as a baby. I thought all babies cried, but my husband, Richard, said his other two children hadn’t cried as much as Danny did. He was married before. Danny’s my only child, so I had nothing to compare him to. But I became exhausted – up most of the night, every night. Danny didn’t seem to need much sleep. I read all the books I could find on parenting. I felt I must be doing something wrong, and if I’m honest Danny’s crying scared me. It seemed as if he wanted something and I should be able to work out what it was. He was out of control when he screamed, even as a baby, and there was nothing I could do to help him.’

‘Didn’t you have anyone you could talk to?’ Terri asked.

‘Not really. I discussed it with my mother when we spoke on the phone, but she said babies often cried for no reason. She lives over a hundred miles from us, so we don’t see her very often. She’s not a hands-on grandmother. Richard’s job was very demanding – it still is – and I’d given up work to look after Danny, so I got up in the night and did most of the parenting. I do now. I tried to keep Danny quiet, because if Richard went to work tired he couldn’t function. I couldn’t function either. I asked the health visitor about Danny’s crying and she said it was nothing to worry about, that it was probably a bit of colic. The gripe water she recommended didn’t help, and Danny kept crying for large parts of every day and most nights until he was eighteen months old. Then it suddenly stopped and he became very quiet and withdrawn. He had some language by then and was starting to put words together into little sentences – you know the sort of thing: “Daddy go work”, “Danny want biscuit”, “Mummy cooking.” But he suddenly stopped talking and would point to what he wanted and make a noise instead. I tried to encourage him to use words, but he would stare through me as though he hadn’t a clue what I was talking about.’

‘Had anything traumatic happened to Danny at that time?’ Terri asked.

‘I’ve wondered that, but I can’t think of anything,’ Reva said. ‘Danny was with me all day and night. I would have known if something had happened. There was nothing.’

Terri nodded. ‘OK. I just wondered.’

‘Although Danny had stopped talking,’ Reva continued, ‘and was very quiet for long periods and all night, he’d started having tantrums. He would throw himself on the floor, screaming, and bang his head on the ground, the wall, a cupboard – any hard object within reach. It was frightening, and when I tried to pick him up he’d lash out, kick and punch me, pull my hair and bite and claw me as though I was attacking him and he had to fight me off. My beautiful baby boy. I was devastated. He’s stopped the clawing, but he still does the other things when he’s frustrated and upset.’ Reva paused.

‘At school we do all we can to encourage Danny to use language to express himself – if he wants something or is upset,’ Sue said.