The Hype Machine

A few hours later, amid reports of heavy intimidation and fraud by the gunmen inside, the Crimean parliament voted to dissolve the government and replace Prime Minister Anatolii Mohyliov with Sergey Aksyonov, whose pro-Russian Unity Party had won only 4 percent of the vote in the previous election. Less than twenty-four hours later, similarly unmarked troops occupied the Simferopol and Sevastopol international airports and set up checkpoints on Crimean roads throughout the region. Two days later Aksyonov, who had earned the nickname “the Goblin” during his days as a businessman with ties both to the Russian mafia and to pro-Russian political and military groups (Aksyonov denies the allegations), wrote a personal letter to Vladimir Putin, in his new capacity as the de facto prime minister of Crimea, formally requesting Russian assistance in maintaining peace and security there.

Before the Ukrainian government could declare Aksyonov’s appointment unconstitutional, pro-Russian protests were whipped up throughout Crimea, developing a groundswell of visible support for reunification with Russia. The sentiment seemed one-sided, with many in Crimea expressing a strong desire to return to Russia. Within hours of Aksyonov requesting assistance, Putin received formal approval from the Russian Federation Council to send in troops. The Russian consulate began issuing passports in Crimea, and Ukrainian journalists were prohibited from entering the region. The next day Ukrainian defenses were under siege by the Black Sea Fleet and the Russian Army. Five days later, just ten days after the ordeal began, the Supreme Council of Crimea voted to re-accede to Russia after sixty years as part of Ukraine.

It was one of the quickest and quietest annexations of the postwar era. As former secretary of state Madeleine Albright testified, it “marked the first time since World War II that European borders have been altered by force.” In just ten days, the region was flipped, like a light switch, from one sovereignty to another with barely a whisper.

The debate about what happened in Crimea continues today. Russia denies it was an annexation. Putin views it, instead, as an accession by Crimea to Russia. His adversaries claim it was a hostile encroachment by a foreign power. In essence, there was a dispute over the will of the Crimean people—a clash of competing realities, if you will. On the one hand, Russia claimed Crimean citizens overwhelmingly supported a return to the Russian Federation. On the other hand, pro-Ukrainian voices claimed the pro-Russian sentiment had been orchestrated by Moscow rather than by the people themselves.

Framing the Crimean reality was essential to restraining foreign intervention in the conflict. If this was an annexation, NATO would surely have to respond. But if this was an accession, overwhelmingly supported by the Crimean people, intervention would be harder to justify. So while the clandestine military and political operations were ruthlessly organized and flawlessly executed, Russia’s information operation, designed to frame the reality of what happened on the ground in Crimea, was even more sophisticated, perhaps the most sophisticated the world had ever seen. And when it came to framing that reality, social media—what I call the Hype Machine—was indispensable.

The Spread of Fake News Online

To communicate my perspective on Crimea, I have to first take you on a detour, through a story within a story, to give you some context for how I understand the events that unfolded in Ukraine. In 2016, two years after the annexation of Crimea, I was in my lab at MIT, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, hard at work on an important research project with my colleagues Soroush Vosoughi and Deb Roy. We had been working for some time, in direct collaboration with Twitter, on what was then the largest-ever longitudinal study of the spread of fake news online. It analyzed the diffusion of all the fact-checked true and false rumors that had ever spread on Twitter, in the ten years from its inception in 2006 to 2017.

This study, which was published on the cover of Science in March 2018, revealed some of the first large-scale evidence on how fake news spreads online. During our research, we discovered what I still, to this day, consider some of the scariest scientific results I have ever encountered. We found that false news diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information—in some cases, by an order of magnitude. Whoever said “a lie travels halfway around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes” was right. We had uncovered a reality-distortion machine in the pipes of social media platforms, through which falsehood traveled like lightning, while the truth dripped along like molasses.

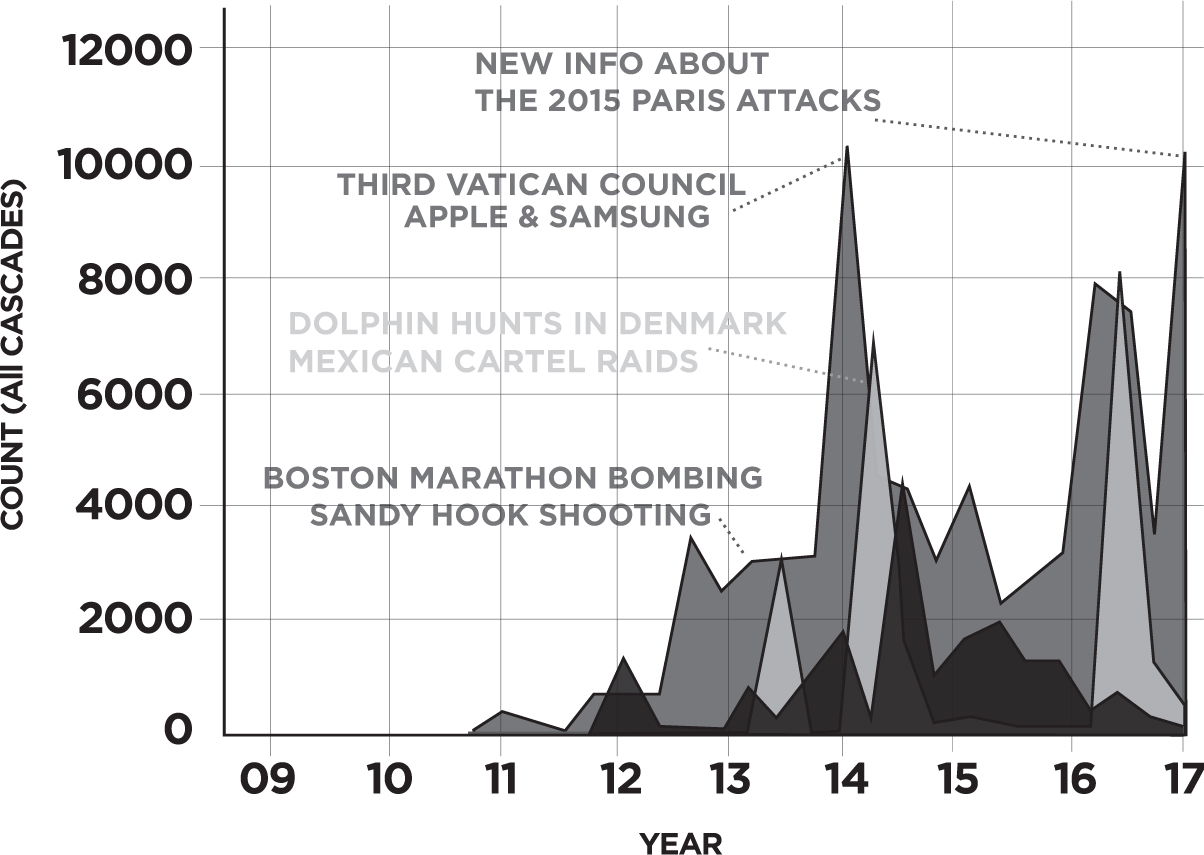

But buried in these more sensational results was a less obvious result, one that is directly relevant to Crimea. As part of our analysis, before building more sophisticated models of the spread of true and false news on Twitter, we produced a simpler graph. We plotted the numbers of true and false news cascades (unbroken chains of person-to-person retweets of a story) in different categories (like politics, business, terrorism, and war) over time (Figure 1.1). The total spread of false rumors had risen over time and peaked at the end of 2013, in 2015, and again at the end of 2016, corresponding to the last U.S. presidential election. The data showed clear increases in the total number of false political rumors during the 2012 and 2016 U.S. presidential elections, confirming the political relevance of the spread of false news.

Figure 1.1 The fact-checked true (light gray), false (dark gray), and mixed (partially true, partially false) (black) news cascades on Twitter from 2009 to 2017. A fact-checked news cascade is a story that was fact-checked by one of six independent fact-checking organizations in our study, diffusing through the Twitter network as it is tweeted and retweeted by Twitter users.

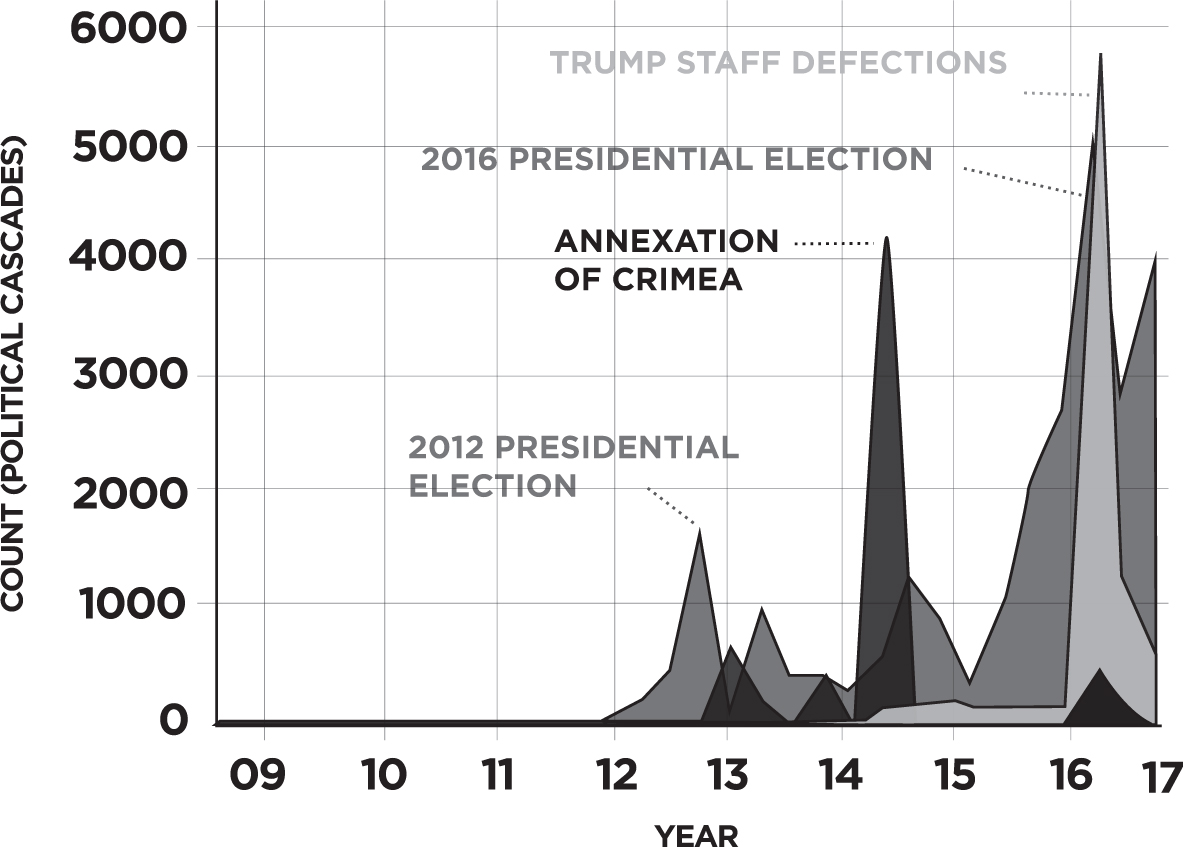

But another, more subtle result also drew our attention. Over the ten-year period from 2006 to 2017, there was only one visible spike in the number of rumors that contained both partially true and partially false information, which we called “mixed” rumors. In the original graph, opposite, it was difficult to see. So we filtered the data and replotted the graph, this time considering only political news. That’s when we saw it—a single, clear spike in the spread of stories that contained partially true and partially false information in the two months between February and March 2014 (See the spike labeled “Annexation of Crimea” in Figure 1.2.) It corresponded directly to the Russian annexation of Crimea.

Figure 1.2 The fact-checked true (light gray), false (dark gray), and mixed (partially true, partially false) (black) political news cascades on Twitter from 2009 to 2017.

This result was striking, not just because it was the largest spike of mixed news in the history of verified stories spreading on Twitter (and more than four times larger than any other spike in mixed political news), but also because it ended almost as quickly as it began, right after the annexation was complete. When we investigated further, we discovered a systematic appropriation of social media by pro-Russian entities that proactively used the Hype Machine to control the Ukrainian national perception of the events in Crimea, and the international perception of what was happening there, to ultimately frame the will of the Crimean people.

Ask Mark

On May 14, 2014, Mark Zuckerberg’s thirtieth birthday, a Facebook user from Israel asked him to intervene against state-sponsored Russian information warfare in Ukraine. Zuckerberg was hosting one of his now famous Q&A Town Halls at Facebook headquarters. These Town Halls are public opportunities for Facebook users worldwide to write in and pose questions about Facebook and its governance directly to Mark himself. On this particular day, the Q&A took place in a moderately sized room at Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park, California. Users had come, some from around the world, to ask questions directly to the CEO of the world’s largest social network.

After a few opening pleasantries, the audience sang a muffled “Happy Birthday” to Zuckerberg, and the questioning began. The moderator, a Facebook employee named Charles, read the first question aloud: “Mark, this question comes from Israel, but is about Ukraine. … It’s from Gregory, and he says, ‘Mark, recently I see many reports of unfair Facebook account blocking, probably as a result of massive fake abuse reports. These often involve the Facebook accounts of many top pro-Ukrainian bloggers and posts about the current Russian-Ukrainian conflict. My question is: Can you or your team please do something to resolve this problem? Maybe create a separate administration for the Ukrainian segment, block abuse reports from Russia, or just monitor the top Ukrainian bloggers more carefully? Help us, please!’ And, as a follow up to this, and we’ll show this on the screen,” said Charles, “the Ukrainian president, Petro Poroshenko, actually sent in a question as well and he asks: ‘Mark, will you establish a Facebook office in Ukraine?’”

If Facebook were a country, it would be the world’s largest, and this was its version of participatory government in action. Mark cleared his throat and noted that he had prepared for this question in advance because, at 45,000 votes, it was “by far the most voted on question we’ve ever had at one of these Q&As.” He then rolled straight into a canned speech about Facebook’s content curation policies.

But the historical significance of what was happening in Crimea far exceeded Zuckerberg’s mundane response. He vastly underestimated the role Facebook was playing in Ukraine in 2014 (just as he would later underestimate Facebook’s role in foreign election meddling in the United States in 2016). The information war in Ukraine was far more complex and consequential than Zuckerberg let on.

InfoWars

After the Facebook Town Hall, it became clearer—through our own research and that of several investigative journalists—that in 2014 Russia had engaged in a complex, two-pronged information warfare strategy in Crimea, using the public application programming interfaces (or APIs) that Facebook and Twitter make available to users to engage with, direct, and orchestrate the flow of information online.

The first prong was designed to suppress pro-Ukrainian voices. If Russia could demonstrate that the overwhelming desire of Crimean citizens was to accede to Russia, they could legitimize their annexation and reframe it as a liberation. Suppressing legitimate pro-Ukrainian voices, therefore, was vital in the fight to orchestrate pro-Russian sentiment in Crimea. This prong’s effectiveness was evident in the pleas for help from the Ukrainian blogging community. Every time a pro-Ukrainian message was posted, it would be overwhelmed by hundreds of fraud and abuse reports, claiming the post contained porn or hate speech. These are common tactics used by Russia’s Internet Research Agency, the shadowy social media organisation, and the subject of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s indictments on a conspiracy to defraud the United States by manipulating the 2016 presidential election. Some have speculated that Russia programmed software robots (or “bots”) to post fraud and abuse claims automatically whenever a pro-Ukrainian voice appeared online. Confronted with thousands of such abuse reports, Facebook took down the “offending” messages and banned their authors, effectively banishing pro-Ukrainian voices from its platform.

The second prong of the information war involved the creation and dissemination of disinformation through fake tweets, posts, blogs, and news. When violent clashes broke out in Odessa on May 2, 2014, between pro-Russian separatists and supporters of an independent Ukraine, a story written by a local doctor, Igor Rozovskiy, was circulated widely on Facebook. Dr. Rozovskiy claimed, in a long, detailed post, that Ukrainian nationalists had prevented him from saving a man wounded during one of the clashes. He said they had shoved him aside aggressively while “vowing that Jews in Odessa would meet the same fate.” He added that “nothing like this happened in my city even under fascist occupation.” The post went viral on Facebook, and translations soon appeared in English, German, and Bulgarian.

A day later, on May 3, Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov gave a speech to the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, in which he claimed that “we all know well who created the crisis in Ukraine and how they did it. … West Ukrainian cities were occupied by armed national radicals, who used extremist, anti-Russian and anti-Semitic slogans. … We hear requests to restrict or punish the use of Russian.” Lavrov’s depiction of the events in Crimea and Ukraine mirrored Dr. Rozovskiy’s perfectly. They both claimed that anti-Semitic Ukrainian nationalists had committed violence against Jews and were threatening to escalate that violence. That same day Ukrainians watched footage of actual violent clashes between pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian forces in Odessa, on television, re-aired repeatedly, visually reinforcing the story. The simple narrative created by Russia, deploying partially true and partially false information, was able to distort reality by altering some but not all of the facts.

So who was Dr. Rozovskiy, and what was his relationship to Russia? It turns out he had no relationship to Russia, or to anyone. His account had been created the day before his post. Dr. Rozovskiy was a fake—he was fake news personified. He was not only parroting the Russian foreign minister nearly verbatim, but this relative newcomer to Facebook, who had no friends and no following, was also going viral in multiple languages.

If you’ll recall, Russian foreign minister Lavrov’s remarks contained an oddly specific assertion, that Ukrainian nationalist radicals were not only threatening violence against Jews but were also planning to “restrict or punish the use of Russian” and that the millions of Russians living in Crimea were outraged by this. While Jews comprise a small fraction of the Crimean population, 77 percent of Crimeans report Russian as their native language. I didn’t think much of Lavrov’s remarks to the UN, until I dug deeper into the massive spike of “mixed” news we had seen in our study of fake news on Twitter during the Crimean annexation.

The most popular mixed news story circulating on Twitter during the annexation claimed that Jews in eastern Ukraine had been given leaflets ordering them to register as Jews or face deportation. The second most popular story claimed the Ukrainian government had “introduced a law abolishing the use of languages other than Ukrainian in official circumstances.” Together, the Crimean stories supported Lavrov’s narrative and accounted for the lion’s share of mixed news stories in Twitter’s recorded history, exceeding every other spike in verified mixed news by a factor of four. The amount of bot activity and the number of unique accounts spreading the disinformation were also statistically significantly higher for the Crimean mixed news stories than for all other verified mixed political news. In social media data, outliers like these typically signal a coordinated attempt to distort reality, an orchestrated effort to influence human thinking and behavior. With Russia claiming vociferously that Crimea desired accession, and with the facts on the ground being distorted by fake news, the Obama Doctrine in response to the annexation stopped short of intervening and imposed economic sanctions instead. And today Crimea is part of Russia.

As dramatic as the Crimean disinformation campaign was, the social and economic impact of social media on our lives far outstrips any single geopolitical event. This same machinery has a hand in business, in politics, and frankly in everything, from the troubling rise of fake news to the rise and fall of the stock market, from our opinions about politics to what products we buy, who we vote for, and even who we love.

The Hype Machine

Every minute of every day, our planet now pulses with trillions of digital social signals, bombarding us with streams of status updates, news stories, tweets, pokes, posts, referrals, advertisements, notifications, shares, check-ins, and ratings from peers in our social networks, news media, advertisers, and the crowd. These signals are delivered to our always-on mobile devices through platforms like Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, YouTube, and Twitter, and they are routed through the human social network by algorithms designed to optimize our connections, accelerate our interactions, and maximize our engagement with tailored streams of content. But at the same time, these signals are much more transformative—they are hypersocializing our society, scaling mass persuasion, and creating a tyranny of trends. They do this by injecting the influence of our peers into our daily decisions, curating population-scale behavior change, and enforcing an attention economy. I call this trifecta of hypersocialization, personalized mass persuasion, and the tyranny of trends the New Social Age.

The striking thing about the New Social Age is that fifteen years ago this cacophony of digital social signals didn’t even exist. Fifteen short years ago, all we had to facilitate our digital connections was the phone, the fax machine, and email. Today, as more and more new social technologies come online, we know less and less about how they are changing us. Why does fake news spread so much faster than the truth online? How did one false tweet wipe out $140 billion in stock market value in minutes? How did Facebook change the 2012 presidential election by tweaking one algorithm? Did Russian social media manipulation flip the 2016 U.S. presidential election? When joggers in Venice, Italy, post their runs to social media, do joggers in Venice, California, run faster? These questions contemplate the disruptive power of social media. By answering them, we can better understand how the Hype Machine impacts our world.

The Hype Machine has created a radical interdependence among us, shaping our thoughts, opinions, and behaviors. This interdependence is enabled by digital networks, like Facebook and Twitter, and guided by machine intelligence, like newsfeed and friend-suggestion algorithms. Together they are remaking the evolution of the human social network and the flow of information through it. These digital networks expose the controls of the Hype Machine to nation-states, businesses, and individuals eager to steer the global conversation toward their ends, to mold public opinion, and ultimately to change what we do. The design of this machine, and how we use it, are reshaping our organizations and our lives. And the Hype Machine is even more relevant today than it was before the COVID-19 pandemic pushed the world onto social media en masse.

By now we’ve all heard the cacophony of naysayers declaring that the sky is falling as new social technologies disrupt our democracies, our economies, and our public health. We’ve seen an explosion of fake news, hate speech, market-destroying false tweets, genocidal violence against minority groups, resurgent disease outbreaks, foreign interventions in democratic elections, and dramatic breaches of privacy. Scandal after scandal has rocked social media giants like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram in what seems like a backlash from which they can never recover.

But when the social media revolution began, the world’s social platforms had an idealistic vision of connecting our world. They planned to give everyone free access to the information, knowledge, and resources they needed to experience intellectual freedom, social and economic opportunity, better health, job mobility, and meaningful social connections. They were going to fight oppression, loneliness, inequality, poverty, and disease. Today, they’ve seemingly exacerbated the very ills they set out to alleviate.

One thing I’ve learned, from twenty years researching and working with social media, is that these technologies hold the potential for exceptional promise and tremendous peril—and neither the promise nor the peril is guaranteed. Social media could deliver an incredible wave of productivity, innovation, social welfare, democratization, equality, health, positivity, unity, and progress. At the same time, it can and, if left unchecked, will deliver death blows to our democracies, our economies, and our public health. Today we are at a crossroads of these realities.

The argument of this book is that we can achieve the promise of social media while avoiding the peril. To do so, we must step out of our tendency to armchair-theorize about how social media affects us and develop a rigorous scientific understanding of how it works. By looking under the hood at how the Hype Machine operates and employing science to decipher its impact, we can collectively steer this ship away from the impending rocks and into calmer waters.

Unfortunately, our understanding and our progress have been impeded by the hype surrounding the Hype Machine. We’ve been overwhelmed by a tidal wave of books, documentaries, and studies of one-off events designed for media attention but lacking rigor and generalizability. The hype is not helpful because it clouds our vision of what we actually know (and don’t know) from the scientific evidence on how social media affects us.

While our discourse has been shrouded in sensational hysteria, the three primary stakeholders at the center of the controversy—the platforms, the politicians, and the people—have all been pointing their fingers at each other. Social media platforms blame our ills on a lack of regulation. Governments blame the platforms for turning a blind eye to the weaponization of their technology. And the people blame their governments and the platforms for inaction. But the truth is, we’ve all been asleep at the switch. In the end, each of us must take responsibility for the part we are playing in the Hype Machine’s current direction.

Not only are we all partly to blame, but we are all partly responsible for what happens next. As Mark Zuckerberg himself has noted, governments will need to adopt sensible, well-informed regulations. The platforms will need to change their policies and their design. And for the sake of ourselves and our children, we will all need to be more responsible in how we use social media in our digital town square. There is no silver bullet for the mess we find ourselves in, but there are solutions.

Achieving the promise of the New Social Age, while avoiding its peril, will require all of us—social media executives, lawmakers, and ordinary citizens—to think carefully about how we approach our new social order. As a society, we will need to utilize the four levers available to us: the money (or financial incentives) created by their business models, the code that governs social platforms, the norms we develop in using these systems, and the laws we write to regulate their market failures. Along the way, we will need to design scientific solutions that balance privacy, free speech, misinformation, innovation, and democracy. This is, no doubt, a monumental responsibility. But considering the overwhelming influence the Hype Machine has on our lives, it is a responsibly we cannot abdicate.

Who Am I?

I’m a scientist, entrepreneur, and investor—in that order. First and foremost, I’m a scientist. I’m a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where I direct the Initiative on the Digital Economy and the Social Analytics Lab, where we study the social technologies that make up the Hype Machine. I earned my PhD at MIT and completed my master’s degrees at the London School of Economics and at Harvard. I’m an applied econometrician by training and have studied sociology, social psychology, and most of the curriculum in the MIT PhD program in economics. I’m a data nerd. I analyze large-scale social media data for a living, to try to make sense of how information and behavior diffuse through social media and society. My real expertise, though, is in graph theory and graph data. In other words, I study things that are connected in complex network structures, whether people in social networks or companies in buyer-supplier relationships.