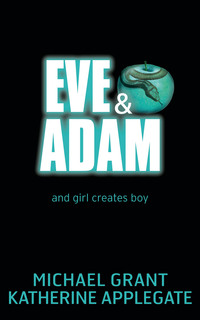

Eve and Adam

The reason no one gets serious about investigating Spiker Biopharm? Because of what happens down there on Level One, that’s why.

The reason so many people think about investigating Spiker? Because of what happens on Levels Seven and Eight.

Me, I live on Level Four. My parents, Isabel and Jeffrey Plissken, were Terra’s business partners way back in the day, when all they had was a broken-down IBM, some petri dishes and a dream.

I don’t remember them. It’s like that.

I could say Terra raised me, but that would be wrong. She’s no mother to me. She gives me a place to live, an education, a job at the lab.

She tolerates me.

She wouldn’t even do that if she knew.

6

EVE

A STEEL DOOR opens and we enter an overlit garage. Two men and a woman, clad in black lab coats like Dr Anderson’s, are waiting for me. I have an entourage.

“She’s stable,” Dr Anderson remarks, “doing well,” and the other three lab coats seem surprised. They mutter medically in ways I can’t decipher.

I am whisked into a long white-tiled tunnel. Solo keeps pace beside me.

We arrive at a large glass elevator. Each member of the group stands before a wall-mounted lens.

“Optical scanner,” Solo explains as a green light clears him.

I’ve only been to my mother’s office a couple of times. (She says mixing home and work is like mixing a single malt with Sprite.) The complex is visually stunning, or at least that’s what Architectural Digest said: “Frank Gehry on steroids.” When you look at satellite photos, you see more security than the Pentagon. Even the security gates have security gates.

It’s the kind of sprawling building you’d expect to find in Silicon Valley, not Marin. But Spiker Biopharm is a different kind of company, my mother likes to say, and I suppose that’s why she decided to locate it in a different kind of place.

“Different” would be her word, but others have had worse things to say. As drug companies go, Spiker’s the bad boy on the Harley your dad doesn’t want you to date. I first realized this in fifth grade, when Ms Zagarenski passed out a form letter soliciting parents to give classroom talks for Career Week. She sent a note home with everybody but me (“Your mother’s so busy, dear”) and I got the clue. Even Danny Rappaport got one, and we all knew his dad ran the largest pot farm in Mendocino.

The elevator shoots to the sixth floor. The doors open to reveal a breathtaking lobby. Marble, glass, steel, tiered fountain. It looks like the Ritz Carlton my dad used to retreat to when the fights dragged on too long.

I’m wondering when the concierge will show up, and suddenly here she is.

“Baby,” says my mother, “welcome to my world.” Burying me in her perfumed embrace, she lowers her voice to a whisper and adds: “Mommy’s going to fix everything.”

She leads the way through swinging doors, and suddenly we are in a hospital.

A really swank hospital.

Dr Anderson has a platoon of assistants: specialists, nurses, techs, but, as far as I can tell, only one patient.

They are shocked at how well I am doing. Everyone wants to have a look at my mangled arm, swollen like an overcooked hot dog. I learn that my spleen, whatever that is, has been ruptured. Also, I’ve lost a rib.

“You’ll never miss it,” Dr Anderson assures me.

The star attraction, however, is my reattached leg with its Frankenstein stitches. My mother is especially interested – my mother, who always made my dad apply Band-Aids because the sight of blood made her woozy.

My gown is an oversized napkin, barely covering the essentials. I’d be massively embarrassed if I weren’t so drugged up. Fortunately, Solo seems to have stayed behind in the hall.

“Miraculous,” breathes a nurse.

It looks horrifying to me, all the blood and goo and gauze, but I have to admit I’m not feeling as awful as I was a few hours ago. The pain has gone from blinding to mere throbbing. And when they finally remove the tube from my throat, the first thing I say is “I’m hungry” in a hoarse whisper, which gives rise to appreciative laughter and applause.

One of the nurses, an older guy with a trim gray beard, introduces me to my room appointments like a bellboy sniffing for a tip. Wi-fi! Flat screen! Italian marble! Heated towel rack!

“Is there anything you need?” my mother asks. “I’m having your pajamas and robe picked up from the house.”

I try to focus. “My laptop. My Titus Andronicus T-shirt, you know, the blue one? Maybe some Clearasil.”

“You won’t be needing your laptop any time soon.”

“Do you know where my phone is?” I croak. “I should call Aislin. I think that guy – Solo? – I think he said somebody turned it in.”

A tight smile. My mother does not like Aislin. She tolerates her the way she tolerated the pet ferret I could never quite housebreak. I believe this is because Aislin shorted out our seven-thousand-dollar, full-body Swedish massage chair with a puked-up Mojito, but Aislin is convinced the tide turned when she suggested a cure for my mother’s chronic headaches. I gather that the phrase “get some” may have been employed.

“Derek, see if Solo has my daughter’s phone.” A tech scurries away, and moments later Solo appears, carrying a plastic bag.

“Someone turned in your cell,” he says. “Also your sketchbook. It’s a little muddy. Nothing too major, though.”

“Thanks,” I say in a dry croak. I sound like my great-grandmother after her nightly Marlboro menthol.

“I’ll take that,” my mother says, but for some reason, Solo refuses to let go of my sketchbook. She yanks and it falls to the floor.

When Solo retrieves the pad, it’s open to a sketch I’ve been working on for several weeks for Life Drawing. We’re supposed to draw a person, either from memory or from our imagination, without referring to a model or a photo.

Easy, I thought.

Turns out: not so easy.

Solo stares at the drawing. It started out as a guy’s face in profile. Not a memory, just something that came to me. Mostly it’s just lines, angles, planes. A preschool Picasso.

It’s deeply lame.

Solo takes it in, meets my eyes.

“Interesting,” my mother says without looking. She plucks the sketchbook away from Solo, snaps it shut and hands it to an assistant.

My mother doesn’t like art, mine or anybody else’s, probably because my dad was an artist. “Austin was a failed sculptor,” she’s fond of saying – she always pauses a beat here, raising a professionally waxed brow – “but he was an accomplished failure.”

“So you’re an artist,” Solo says.

“She’s a patient,” my mother answers, “and she needs to rest.”

“Right.” Solo starts to hand her my phone.

“No,” I say quickly. “Would you check for messages first? The password’s 0123.”

“Impenetrable.” Solo scans my mail. “Aislin wants to know WTF are you dead or what OMG please please please call.”

“Didn’t you call her?” I ask my mother. “She must be so –”

“I’ve been a little busy, dear,” my mother says crisply. “I’ll have someone give her a call, let her know you’re all right.”

I can tell she’s planning to forget to remember. “Would you do it?” I ask Solo. I don’t know why him exactly, except that he’s still holding my phone.

“Sure. No problem.”

He taps the screen. “Got it. Don’t worry. I have a photographic memory.”

“Really?” I ask vaguely. Suddenly I am incredibly weary.

“Just for things that matter,” Solo replies.

His gaze lingers on my leg, then moves on to my middle. I am not sure if he’s staring at my flattened arm or my boobs (also pretty flat), but either way, I’m not dressed for company.

He meets my eyes for just a moment. Then he hands my mother my cell and makes his way past my bedside fan club.

7

I WAKE UP hours later, clawing my way out of the Vicodin haze. It’s dark, but my room is lit with soft yellow light. If I squint just right, I could be in a romantic restaurant. On a really bad date.

The first thing I see is Solo, looking with intense focus at the iPad they use in lieu of an old-fashioned clipboard medical chart. It’s not the concentration of someone trying to make sense of something he doesn’t understand. It’s the concentration of a guy confirming something he already suspected.

He hears me moving. The iPad is back in the slot at the foot of my bed and he’s smiling at me. Covering up. Looking innocent.

I think: Strange boy I really don ’t know, don ’t you realize nothing is more suspicious than an innocent look ?

Before I can say anything, Solo slips out the door. Seconds later, a nurse arrives. I haven’t seen her before, so I figure she must be part of the evening shift.

I close my eyes, pretending to sleep. I’m not in the mood to chat.

She checks the bandage on my leg. It’s one hell of a bandage. Gently she begins to cut away the tape and gauze and pressure mesh. It doesn’t hurt, but it doesn’t make me happy, either.

“Oh my God!” she says.

She has laid the flesh bare and her first thought is to call up a deity.

I risk a slit eye to see what horror she’s witnessed.

She’s not looking at my face. She’s staring down at my leg. And she’s not horrified, exactly.

She’s amazed. She’s moved. She’s seeing something she never expected to see and can’t quite believe is real.

I’m afraid to look, because I know that something must be very wrong.

Or, just possibly, very right.

8

SOLO

THE SPIKER COMPLEX has an amazing gym. Everyone is constantly nagged to stay in shape. I don’t need to be nagged and I don’t need to be coached. I need to be left alone.

I run on the inside track. I run barefoot, I prefer it. The soles of my feet make a different sound, nothing like those three-hundred-dollar running shoes, groaning as all that shock-absorbing rubber takes the impact. My feet are almost silent.

I run and then I hit the weights, the crunches, all that. I like weights – they’re specific. There’s no bull in weightlifting, you either get that seventy pound dumbbell up to your chest or you don’t. Yes or no, no kind-of.

After weights I go into the dark, smelly side room where the speedballs and heavy bags are. The rest of the massive gym complex is spotless and bright and gazed-down-upon by screens.

The boxing room – well, there’s just something seedy about the sport that comes through, even if the designer you hired insisted on a lovely shade of teal for the ring ropes.

Pete’s there, all ready to go.

Sometimes I go rounds with Pete. Pete’s older than me, maybe twenty-five. I’ve never asked. But he’s one of the geeks so we tend to get along well. We speak geek, or we would if we didn’t have slobbery mouthpieces in and weren’t beating on each other.

Pete’s not as quick as I am, and he looks softer and spongier than I do. But damn, when he connects you know you’ve been hit. You know it and you have to acknowledge it as your brain spins inside its bone cradle trying to reconnect all the switches.

I kind of love it.

You take a hard one to the side of your head, a shot that makes you feel as if you aren’t wearing sparring headgear at all, one that rings the bells in your ear, and then you come back from it, still swinging? To me that’s one of life’s finest moments.

Hit me. No, I mean hit me hard. Turn my knees to overcooked linguine.

And I take it and come back with a combination? Prodigious.

I’m done and covered in sweat. From the hair on my head down to my feet: wet, shiny, panting, grinning, wondering if I’m going to get feeling back in the left side of my face.

“Wimp,” Pete says.

“Weakling,” I respond.

“I don’t feel right beating up on a little girl.”

“Don’t feel bad, Pete. Keep at it and you may learn to throw a punch that actually connects some day.”

With our ritual abuse concluded, we make an appointment for the day after tomorrow. Pete heads for the gym’s showers, I head for my quarters.

My quarters, my place, my space. It’s on Level Four, where Spiker maintains rooms for visiting scientists and dignitaries. Some of those rooms are amazing. My quarters do not justify the word “amazing”, but they aren’t bad.

In any case, this place is a major improvement on the boarding school in Montana that Terra shipped me off to after my parents died. Some kind of tough love dude ranch high school for troubled kids called Distant Drummer Academy. I wasn’t troubled – unless you count being orphaned overnight – and I wasn’t in high school, but Terra provided them with a nice diagnosis of severe ODD. And a hefty donation.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder? Yeah, I can do that.

I lasted eight days.

After they kicked me out, Terra gave me two options: I could live at her place, or I could live at Spiker.

We both knew which one I’d choose.

I have a single room, but it’s big enough for a queen-sized bed and a sofa, TV, desk, beanbag chair, and mini kitchen. Except for the two framed photos on my desk, it’s as sterile as a hotel room. I like it that way.

I barely notice the photos any more. There’s one of my parents at a podium, my mom in a shimmering green evening gown, my dad in a tux. They’re accepting an award, flashing smiles. And there’s one of me and my mom reading a book together. We’re in some kind of waiting room, sitting on orange vinyl chairs. I don’t remember where it was, or why we were there.

But then, I don’t remember much of anything.

Next to the mini kitchen is a small bathroom. That’s where I strip down, soap up and shower off.

That’s where I start thinking about the girl.

Like I don’t know her name: the girl. Please, Solo. I know her name. Evening. E.V. to her friends.

Eve.

There’s a problem with that name, Eve. You say “Eve” and you think Garden of Eden, and then you think of Eve and Adam, naked but tastefully concealed by strategic shrubbery.

Except at this particular moment, my brain is not generating shrubbery.

The girl had her leg chopped off. She just got out of surgery. So I add shrubbery.

And yet the shrubbery doesn’t stay put. It’s moving shrubbery. It’s disappearing shrubbery.

I step back under the twin shower heads and blast myself with hot water. Maybe I should make it cold water. But I don’t want to.

“That’s the problem with you, dude,” I say, speaking to myself. “You suck at doing things you don’t want to do.”

I don’t feel bad speaking to myself.

Who else have I got?

Solo isn’t just a name, it’s a description. I have no actual friends. I have some online ones, but that’s not quite the same.

I’ve never had a girlfriend.

When I touched Eve, she was the first girl I’d touched since coming here to live six years ago. Unless you count female scientists and techs and office workers I’ve accidentally brushed in the hallways.

Sometimes I do count those. It’s a normal human behavior to count whatever you have to count.

“Back up, man,” I tell myself softly. “She’s a Spiker. She’s one of the enemy.”

The microphones won’t pick up what I say with the shower running. I know these things. Even though I’m not supposed to. For six years I’ve lived and breathed this place. I know it. I know it all.

And I know what I’m going to do with it.

As soon as Eve is gone.

9

EVE

THREE LITTLE DAYS, but oh my God, can they be long.

Time is relative. An hour spent watching paint dry is much longer than an hour getting a massage.

Which is exactly what I’m doing. Getting a massage from Luna, the massage therapist.

Luna doesn’t touch The Leg.

In my head, The Leg is capitalized because The Leg is what my whole life seems to be about now. Every single person I’ve seen in the past few days asks me about The Leg.

How is it?

How’s The Leg?

The Leg is attached. Thanks for asking. There’s The Leg right there. It’s on display, always outside of the sheets and blanket, although the whole thing is still so wrapped up it looks like I borrowed The Leg from some ancient Egyptian mummy.

How’s The Leg?

It seems a bit mummyish, thanks.

I had a dream where The Leg was no longer attached. Not a happy dream, that. It scared me. I try to be glib and tough and all SEAL Team Six about it, but in all desperate seriousness: I was scared.

“I need Aislin,” I say to my mother.

“Aislin is a drunken slut,” she replies, without looking up from her laptop.

This is diplomatic for her.

I decide to change the subject. “What are you working on?”

With effort, she pulls her gaze from the screen.“Fluff. A vanity project for one of the biochems.”

“Fluff ?”

“Educational software. Project 88715.”

“Catchy. The kids’ll eat that up.”

“Mm-hmm.” She returns to her screen.

“Aislin is not a slut,” I say. I don’t deny the drunken part. “She’s been in a steady relationship for months. Anyway, she’s my friend. I miss her.”

“Talk to the masseuse,” my mother says. She glares at Luna. “Who are you? Talk to my daughter.”

I feel the tremor go through Luna. Luna is probably fifty years old, a very nice Haitian woman. I like Luna. She doesn’t hurt me as much as the various other physical therapists.

Luna has six kids. Two are in college and one is a real estate broker in San Rafael.

Number of things I have in common with Luna? Zero.

“I want my friends,” I say.

“Pfff. Friends, plural?” my mother asks. “Since when do you have friends, plural? You have one friend and she’s a drunken slut.”

“I’m lonely. There aren’t even any other patients. The only one around who’s my age is Solo.”

“You haven’t talked to him, have you?” my mother asks, feigning a casual tone. Casual, like warm and fuzzy, is not part of her emotional repertoire.

“No,” I lie, wondering why she cares.

Actually, I’ve seen him every day since my arrival, passing by my room with studied indifference. He only spoke once, to tell me that he called Aislin and told her not to worry about me.

His eyes are disturbingly blue.

Against my better judgment I ask, “Who is Solo, anyway? And why is he here?”

My mother ignores me. She has different Ignore settings, and this one means she’s hiding something. She thinks she is inscrutable, and maybe she is, to her minions, but I’ve had seventeen years to deconstruct her poker face.

Before I can press her to answer, Dr Anderson strides purposefully into the room. He always strides purposefully, although he doesn’t seem to have much purpose, what with me being his sole patient.

“How’s The Leg?” he asks.

“The Leg is bored,” I answer. “The Leg wants to know why it can’t go home and recover.”

“You’ve been here three days, Evening! Are you insane?” my mother cries.

“I should leave,” Luna says meekly, half-question, half-hope.

“Stay,” my mother commands. “Calm her down.”

“I don’t need to be calmed down. I need Aislin. I need something to do.”

“You have to take this slowly, Evening,” Dr Anderson intones. He has perfect teeth and the graying temples of a Just For Men model. “This kind of recovery is measured in months, not days.”

“I’m missing the end of the school year.” I am starting to feel quite sorry for myself. “I have homework, tests. Oh crap, my Bio exam is Tuesday! And my Life Drawing project is half my semester grade.”

“You can’t draw,” my mother says. “Your fingers are crushed. Your arm’s a mess.” She pauses, mentally thumbing through her What Mothers Are Supposed To Know file. “She is right-handed, isn’t she?” she asks Dr Anderson.

He nods discreetly.

“At least can I have my laptop? I can type with my left hand.”

My mother glances at her own laptop.

She is having an inspiration. You can practically see the giant light bulb throbbing over her head.“Evening, I have just the project for you! Something to keep you thoroughly occupied.”

“I don’t want a project. I want to spend a couple of hours with Aislin. I want you to send a car for her and bring her here.”

Luna has moved to my lower back, and seriously, my desire to fight with my mother – even if it is a respite from boredom – is diminishing with each deep, healing stroke.

“It involves genetics.” My mother sets aside her computer and comes to my bedside. “You love genetics. I would even pay you to do it.”

“Pay me?”

“Why not? I’d have to pay someone else to test it. What do you want? A hundred dollars? A thousand?”

My mother, ladies and gentlemen: one of America’s pre-eminent businesswomen. Not a clue as to what a dollar is.

“I want ten thousand dollars,” I say.

Dr Anderson nods his approval.

“Is that a good number?” my mother asks. She turns the question over to Luna. “Is that a good number?”

“Ma’am, I don’t –”

“Whatever,” my mother snaps. She makes a brusque gesture with her hand. “The point is, I have something that will keep you busy.”

“Aislin will keep me busy. That’s my price: Aislin. You can keep the money.”

She taps her freshly tended nails. French manicures, twice a week. Five tiny crescent moons dance on my bed rail.

She sighs.

Dr Anderson examines a smudge on his stethoscope.

“One visit,” my mother says at last. “I’ll have security search her. If she has any drugs or booze on her, I’ll confiscate them and have security rough her up.”

I assume that’s bluster.

Then I look at her again, at my mother, and I’m not so sure it is. This is a woman with a multi-billion dollar company. This building is big enough to house what amounts to a small hospital among many, many other things.

Can my mother actually have people beaten up?

Maybe. Maybe she can.

She smiles to show she doesn’t mean it. The smile convinces me that she can.

“So what’s the project? You want me to wash some test tubes?”

“No, that’s why we have people like Solo,” she says. “You’re a Spiker.”

I feel a twinge of sympathy for Solo. I’d been assuming he’s some kind of wunderkind, and here she’s talking about him as if he were a janitor.

People like . . .

Quite a bit of condescension locked up in those two words.

“This will be a wonderful introduction to the kind of thinking and creativity we require at Spiker,” my mother says. “It’ll challenge you, sweetheart. Bring out the talent I know you have hidden deep, deep down inside you.” She’s getting excited now. The lines in her forehead seem to smooth, her eyes gaze with a certain wild excitement at the horizon.

She pauses, waiting to be sure she has my undivided attention.

“I want you, Evening, to design the perfect boy.”

Luna stops rubbing.

“Am I doing this with crayons? Or will I be working with Play-Doh?”

My mother smiles tolerantly. “Oh, I think we can do a little better than that. You can start tomorrow morning. If you do it, I’ll have your little friend here tomorrow afternoon.”

“I think Aislin has her dance class on –”

“Evening. When I send for people, they come.”

10

“THIS IS WHERE you’ll be working. Playing.”

My mother hesitates, frowns, realizes she’s frowning and that frowning causes lines, and unfrowns. “Play, work, call it whatever you like.”

“So long as I do it.”

“Exactly.”