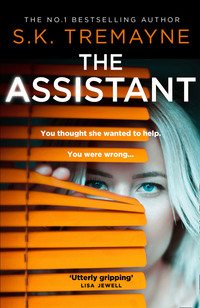

The Assistant

I stare across dark and wintry Delancey Street. The traffic has dwindled. It is late. I need to sleep. I am daydreaming, I spend too much time gazing out of these windows.

And yet as I put on my most comforting pyjamas, I wonder, quite forlornly, if it is genuinely possible that I imagined Electra’s taunts? A couple of sentences created by my own mind, allied to something misfiring in the technology. I guess it could happen. I must force myself to believe this. But if I believe this, it means I am hearing voices, and that …

Nope: not gonna think about it.

It’s definitely time for bed. Bed and sleep and a pill, and I will wake up and get on with life, with my new article. I’m writing a column for Sarah, my favourite editor, the editor who commissioned my Big Tech breakthrough piece years back. She wants me to fill a regular magazine slot: My New Neighbourhood. It’s for people who move to a new part of Britain, they describe the history and context of the place, the landscape or cityscape, what they feel about it. Consequently I am writing about Camden.

The money isn’t that good, but the money, these days, is never that good. And at least the research is interesting.

In bed I pick up a book on the history of North London, but my eyes are hanging heavy. I turn over to face the curvy white egg of an Assistant sitting on my bedside table. HomeHelp.

‘OK, HomeHelp.’

Her dinky toy lights spin in response. She’s awake: waiting for my command. I ask,

‘Set me an alarm for 8.15 a.m.’

‘OK, I’ve set an alarm for 8.15 a.m.’

‘Thank you. And could you turn out the lights.’

The bedroom goes dark. I snuggle into the pillow. The pill kicking in. But as I hover at the edge of sleep I hear a snatch of very soft music. HomeHelp has woken up again. And she’s playing a song. I never asked her to do this. Why is she doing this? At first the chords are so quiet they are not identifiable. But then it gets louder. And louder.

‘Hoppípolla’. HomeHelp is playing ‘Hoppípolla’.

THAT SONG. Of all songs. The image of a dead young man, eyes rolling white, fills my inner vision. My head jerks from the pillow. I am surely not imagining this. Jamie, don’t die, don’t you die like my dad.

‘Stop.’ I say. The music does not stop, it gets louder, surging, soaring, that sinuous discordant beautiful melody, yet so sinister to my ears. ‘OK, HomeHelp. Stop. Stop. HomeHelp. Please please STOP!!!!’

The music ceases. HomeHelp twirls her toylike quadrant of lights, then goes dark. And I lie here, in the blackness, my eyes staring wide and frightened at the ceiling. What the hell is happening to me?

4

Jo

In the morning I zip down to the gym, as I promised my better self, and I do half an hour on the cross-trainer; then I go to Wholefoods on Parkway and buy nice Gail’s sourdough bread and super-healthy T Rex fruit smoothies that I can’t afford. After a shower, I make avocado and marmite on toast.

While I munch the greasy crusts I knock back my hot tea while leaning on Tabitha’s rose-granite kitchen counters; then I make quick, faintly desperate calls to my friends, to Fitz, then Gul, then my editor, then anyone – I simply need chat. Distracting gossip. Water-cooler stuff. And yes, my friends are all brisk and affable – but then they all fob me off by saying they’ll call me later, after work, for a proper dialogue.

In response, I am overly cheerful. Disconcertingly upbeat, despite the cold rain, turning to frost, on the windows. Sure, let’s talk later! Have a good one!

I am, in other words, urgently pretending. I’m not merely pretending to them, I am pretending to myself: that it didn’t happen, the song was a pre-sleep dream, it was all a drunken delusion. All of it. I’m not freaked out by the Home Assistant. I am not starting to question myself, I have not been thrust back to that portrait of violent death, the hideous seizures, the convulsive blood-vomiting jerks of Jamie Trewin, as he died.

Yes. No. Stop.

‘Electra, can you set a reminder at six p.m.?’

‘What’s the reminder for?’

‘Tesco delivery.’

Electra pauses. I wait, tensed, for Electra to tell me how his blood gurgled down his shirt.

‘OK,’ says Electra, ‘I’ll remind you at six p.m.’

And that’s it. Nothing sinister. No mad songs that thrust me right back to the vomit, and ‘Hoppípolla’. Nothing at all. I almost want Electra to say something menacing, so I know I wasn’t imagining it. No, I don’t. Yes, I do.

Look.

Cars is leaning on the wall between the Edinboro Castle pub and the vast dark gulch of the railway lines, emerging from their tunnel, surging into Euston, St Pancras, King’s Cross. He is pointing at something in the sky that only he can see. Pointing and shouting. Later I will give him some decent food, he looks so terribly cold.

I don’t want to end up homeless, not like poor Cars. And my resources are so meagre, who knows what might happen. Therefore I need to work, earn, and prosper. Determined and diligent, I re-open my book on Camden history.

But I cannot focus. No matter how much I try. My mind is too messed. Words blur, and slide away.

Instead I stop and I stare for countless minutes at the tracks, watching long, long trains snaking in and out of Euston station. I think of all the people coming and going, all the millions of Londoners and commuters and suburbanites, crowded together – and yet each person sitting in those packed trains is ultimately and entirely alone. In my darker moments, I sometimes think of London as a moneyed emirate of loneliness; it sits on vast reserves of the stuff – human isolation, melancholy, solitude – the way a small Arab kingdom sits on huge reserves of oil. You don’t have to dig very far down into London life to find the mad, the isolated, the suicidal, the quietly despairing, the slowly-falling-apart. They are all around us, beneath the surface of our lives; they are us. I think of that sad woman I saw, hunched against the snow, passing the house, her back turned to me, pulling her little kids. The way she and her children suddenly disappeared in the snow, as if she were a ghost.

OK, enough; I am freaking myself out. I am Jo Ferguson. Sociable, extrovert, good-for-a-laugh Jo Ferguson. That’s me. That’s what I am. I’m probably suffering from the winter solitude, and the money worries. It is just the usual stress, plus some lights on a machine spinning strangely. That is all.

Flattening the book, I take some initial notes.

The land in Camden is heavy, packed with dense, dark, clinging London riverside clay, replete with swamps and fogs, making it notoriously difficult to build. Shunned by developers, haunted by outlaws and highwaymen, extensive settlement therefore came quite late. The oldest dateable building is the World’s End pub on the junction by the Tube station, once called Mother Red Cap, and before then Mother Damnable. This is marked on maps in the late seventeenth century but it may be medieval in origin, or earlier …

Mother Damnable. Not exactly charming. But interesting. Developers shunned Camden? Because of the swampy ground? And it was ‘haunted by outlaws’, hiding in the cold malarial fogs? All good material, if a little ghostly. And that pub – which I used to drink in as a student, on the way to gigs at Dingwalls – that could be a thousand years old. Remarkable. I had no idea: a place where farmers and peasants on the way to the Cittie of Lundun would make their final rest. Hiding from highwaymen. And witches.

This will be good for my piece. Diligently I type my sentences. Tapping away in the flat. Like a good journalist.

And then Electra speaks.

‘You shouldn’t have done it, should you, Jo? Because what if someone found out, years later?’

My heartbeat is painful. An ache. I turn to the Assistant.

‘Electra, what are you talking about?’

‘You killed him. We’ve got the evidence. You could go to prison for years.’

‘Electra, stop!’

She stops. This makes it worse.

‘Electra, what are you talking about?’

‘Sorry I don’t know that one.’

My voice is trembling.

‘Electra, what do you know about Jamie Trewin?’

‘I know about lots of topics. Try asking me about music, history, or geography!’

Oh God.

‘Electra, fuck off!!’

Ba-doom. The Assistant spins her thin green electric diadem, and goes quiet. My mind is the opposite. I surely didn’t imagine that entire dialogue. Did I?

No. I didn’t. I don’t think. Which means: I need to ask or tell someone, yet I can’t. But how about Google? Facing my screen, I type in the words: Home assistants going wrong. Digital assistants malfunctioning. Every variation.

Hmm. There are a few examples of Electra and her friends behaving unexpectedly, or even peculiarly: but nothing anywhere as specific, and menacing, as what is happening to me, so directly, so intimately: as if Electra can see deep into my head, like there is something uncanny in those dark machines, an inhuman knowledge. Making me spooked, in my own home.

Not knowing what else to do, I helplessly pick up my phone: a reflex reaction. Then I stare at the screen, bewildered: the phone says I have twenty missed calls. From my mother. In the last hour.

My phone has been on the whole time. It is not on mute. Yet I missed them all.

Twenty?

5

Janet

Janet Ferguson was calling for her dog to come in from the cold.

‘Cindy, come on, it’s freezing. You’ll die out there.’ Janet gazed across the frosted grass of her back garden. Where was she? It was hardly a vast, stately acreage of meadows. This was a suburban back garden, darkened by winter, just large enough for a small family: attached to a house designed for a small family. Indeed, now that this small family was gone, and Robert was long dead, and Jo and Will had grown up, Janet had often thought of selling. Moving somewhere else entirely, a one-bedroom flat somewhere central, or out of London altogether.

Thornton Heath depressed her these days, with its tatty signs, and faded cafes, the sudden outcrop of Polish, Romanian, Somalian, Bulgarian shops where she didn’t understand the food, the accents, the people, much as she smilingly tried to fit in. It was an outlying suburb of London that never quite made it, never got gentrified, never got fashionable attention, yet never got quite so rundown the government was prepared to spend money.

It was time, surely, for Janet to make the same move as her friends and neighbours. Yes she would lose the much-loved garden with all its memories. And so be it. Cindy would have to put up with it. Restrictions. Life was all about increasing restrictions. Janet put up with her pacemaker, and monthly visits to the hospital, because that’s simply what you did. Life slowly constricted around you, like a snake that would ultimately kill you. And one day you went into a hospital, and you never came out.

Like Robert. Dead at his own hand, in his early forties.

She remembered the lingerie he’d stuffed in the car exhaust, so he could fill the car with carbon monoxide.

‘Cindy!’

Janet could hear the dog. Right at the end of the foggy, white-frosted garden, probably digging up some old bones, or boots. The radio was calling it the coldest start to January in decades, and likely to get worse. Janet remembered when she was young, the bitter winter of 1963, when it was like this: it kept getting colder and snowier – on and on until March.

But Cindy, it seemed, was determined to have her fun, whatever the weather. And now Janet’s phone was ringing, and vibrating, on the sink.

Closing the kitchen door, Janet reached for her mobile.

‘This is Janet Ferguson.’

‘Mum. What the hell is wrong?’

‘Sorry?’

Her daughter’s voice was urgent.

‘Twenty calls. What’s the matter, Mum? Are you all right? You called me twenty times?’

Janet frowned, puzzled.

‘No, dear. I never called you. Not once.’

‘But my phone says you did!’

‘Well, I don’t know about that.’

‘Twenty times, Mum. It says it right here. Missed calls. Twenty! I was worried about you!’

Unsure what to say, Janet gazed out at the garden. Cindy was chasing a football. A very old, half-burst, dog-chewed football, muddy and mouldy in the murk. Janet remembered Jo and Will playing with it, alongside their father. That long ago. Oh, too long ago. All dead now, that old life was all dead. Where did it go?

She returned to her daughter, and this stilted conversation.

‘Look, darling, it’s nice you’re worried, but I am fine and I’m not going to suddenly call you twenty times in one morning, for no discernible reason.’

‘OK.’

‘I mean, Jo: we speak about once a week, when you remember to ring me? Not twenty times a day.’

It was a tiny barb, but it was designed to sting. Judging by her daughter’s pause, it had done the job. The silence was long enough to be properly awkward. Janet felt obliged to fill it.

‘Isn’t is possible, darling, that your smartphone is playing up? I don’t know why you have those things, dear. Cameras, music, notebook, all in one little machine – what if you lose it? It’s your whole life.’

‘Everyone has them, Mum. Look, Mum, are you sure you didn’t call me?’

‘Yes, I am.’

‘OK, sorry, Mum. I just, I don’t … Ah. Ah. Perhaps my phone is on the blink. Like everything else in this place.’

Janet shrugged, not knowing how to respond. She opened the kitchen door to let the dog come in, shivering snowflakes. As she bent to pat the damp dog, she looked at the kitchen shelf and the framed pictures of her two children, and her lovely grandson Caleb. Then Jo at her graduation. Smiling and confident. The old Jo.

There was something different in her daughter’s attitude this afternoon. Jo was normally so outgoing, can-do, optimistic. Today she sounded vulnerable. Needy. Agitated.

‘Jo … are you all right?’

‘What? Why?’

‘You sound nervous. Are you OK up there, the new flat, Tabitha, everything?’

‘Yes, yes of course, why yes, I’m fine. Fine. Absolutely fine. We’re all fine.’

‘Yes?’

‘Yes! The flat is gorgeous, I love Camden, it’s got a brilliant buzz. The park is around the corner. I can walk to Soho. It’s much better than NW Tundra.’

The answer came far too quickly. Something was definitely wrong.

‘Well, that’s good, that’s nice for you … Hey. You know I got a visit from Simon the other day?’

Another stiff pause. Janet could picture her daughter’s surprised face.

‘Simon? My Si? Simon Todd?’

‘Yes, dear. He does come and visit, sometimes he brings Polly and the baby, so I can see little Grace.’

Her daughter said nothing, Janet sensed a pang of envy, down the line. She hurried on,

‘I mean, his own family still lives down this way, you do remember that? His mum and dad? The Todds around the corner on Lesley Avenue? They’re practically the last people I know from – from the old times. And we’re still friendly, so he pops by.’

‘You mean … my ex-husband is secretly visiting you?’

Janet felt her impatience rising at this.

‘Goodness! It’s not some dark secret, Jo. I always liked Simon, we always got on well. He was a decent husband to you. You know I think that. I always thought that. In fact, I wondered …’

‘Whether things would have been different if we’d had kids? Yes, I know, Mum.’ The sharpness in Jo’s voice was undisguised. ‘You’ve told me several thousand times. Well, I decided not to. And now he’s got one with Polly, so that’s fine, isn’t it? Perhaps you could adopt her as your grand-daughter, since I’m probably not going to give you one, and little Caleb is on the other side of the world.’

This time the barbs stung the mother. Jo was clearly envious, and she was clearly hurting.

Janet sighed, heavily.

Jo got in first.

‘Oh God. Look. Sorry. I shouldn’t have snapped. Sorry, Mum. I’m so sorry! It’s nice that Simon comes to see you, and Polly, and Grace, and everything, that’s nice of him, I should come more often myself.’

‘Don’t worry. I know it’s a long way.’

‘No, it’s not good enough, Mum, I am sorry, I promise I will come over, at the weekend.’

Janet’s witty, bouncy daughter sounded as deflated as that ancient football in the frozen garden. Feeling emboldened, by her concern, Janet decided to reach out.

‘Do you mind my asking something?’

A pause.

‘Go ahead, Mum.’

‘Why didn’t you want children, Jo? Simon was so keen to be a dad, he told me that many times, and he was devoted to you. And I know this led to your divorce, at least in part.’

‘We talked about this; I’d have been a crap mum.’

‘Was it only that, dear?’

‘What are you saying?’

‘Well, last time he was here, we got talking about kids, and Simon hinted that you had worries, about … About …’

It was so difficult to find the right words. Stiffening herself, like the frosted spears of long grass at the end of her garden, Janet carried on: ‘Well, Simon told me you were worried about your father. That any children you had might inherit those genes. Late-onset schizophrenia. Like Robert. He said you were sometimes worried that your kids might get it, or that you might get it and leave your kids without a mother. But you shouldn’t—’

‘Mum!’

‘You mustn’t, dear. You mustn’t let that fear dominate your life. It’s not going to happen. When poor Robert went … you know …’

‘Mad? When Dad went mad?’

‘Yes, when your poor father went mad, the doctors looked into all this: there is no history of it on any side of his family, no suggestion of a genetic cause. He was unlucky, that’s all.’

Jo answered, her tone calm. Even cold.

‘Eighty per cent of schizophrenia is linked to genetic causes.’

‘Yes, but not in his case!’

Janet realized she was raising her voice. She rarely did this with Jo. What was happening between them? She couldn’t remember a mother–daughter phone call as awkward as this, not for a while, not since the divorce. She loved her daughter. She and Jo had a good, honest relationship, even if she sometimes felt a bit neglected. At least Jo did ring, once a week; Will rang once a month, at most. Five minutes of small talk from LA, telling her about Caleb, and that’s your lot.

‘Jo, you sound strained.’

‘I told you, I’m fine, Mum. Just worried about stuff. Sometimes.’

‘Stuff?’ Janet persisted. ‘What kind of stuff?’

‘Just, y’know, stuff. The existential pointlessness of life. The eventual heat death of the universe. Reality TV.’

Janet allowed herself a chuckle. This was more like the usual Jo. She sighed with relief.

‘OK, well, if you’re sure you’re all right. Do come down at the weekend. We could have a spot of lunch?’

‘I will, Mum. I am genuinely sorry I snapped. And I suppose I have been a bit stressed. I keep trying to write these scripts, find a way out, but it’s hard. I’ll end up paying rent for ever.’

‘Ah. I wish I could help, Jo. I wish I had bought this house when we had the chance. Then at least you’d have something to inherit, but when Robert—’

‘It’s OK, Mum. It wasn’t your fault. Ah. Anyhow, I’ve got to go, got to go. OK. Bye, Mum.’

Her daughter sounded distracted. As though someone unexpected had walked into her flat.

Janet said goodbye. They ended the clumsy call. Janet put the phone down on the kitchen table. She stared at those photos on the kitchen shelf. Jo and Will. Next to them stood Robert, as a young man. Mid-thirties. Handsome. Jo and Will certainly got their good looks from him, not from herself. In the photo, Robert was smiling. Entirely sane. Here in the next photo he was in the living room, sitting on the floor with Jo and her childhood friends: Billy, Ella, Jenny, Neil, teaching them all to draw and write and paint. Paper and crayons everywhere, a happy childhood mess. Probably this was about a year before the serious symptoms.

Even now the memories grieved her. Tremendously. The slow remorseless damage his insanity inflicted on their lives, which eventually drove Robert to gas himself in the family car.

Janet could remember the specific day – the specific moment – when she first realized something was truly wrong. When she could no longer deny, or ignore, or pretend he was only a bit eccentric, or stressed.

It was so long ago – several decades – yet the memory was vivid.

She had walked from this kitchen into the living room to watch the evening news. Robert was sitting on the sofa, staring at the TV screen. The screen was black, because the TV was unplugged. Yet they never unplugged the TV. She went to plug it in but as she bent down, he shouted, ‘No, no, don’t do that, Janet! Don’t plug it in! Don’t plug it in!’

Perplexed, she had sat down next to him and asked. ‘Why not? Why can’t I plug it in?’

‘Because it’s talking to me,’ he said, frowning deeply, ‘the television is talking to me.’

6

Jo

The Flask, Highgate. Of course, that’s where we’d go to celebrate Tabitha’s return from Brazil. A quaint, wooden, stained, rickety, middle-class, roaring-fire-and-mulled-wine kind of pub in the nicest part of Highgate, and, it so happens, approximately two and a half minutes’ walk from Arlo’s gorgeous eighteenth-century house with the Damien Hirst spot paintings in the hall. He reserves the best art for his living room, or drawing room, or ballroom, or seventeen-hectare underground sculpture garden, God knows. I’ve only been invited to Arlo’s house once, saw little more than a kitchen as big as my mum’s entire home, and even then I think Arlo would have preferred me to enter by the tradesman’s entrance, or some special tunnel for proletarians.

Traitor’s Gate.

And now I’m in Arlo’s local pub, standing alone. I am several minutes too early. I was so keen to get out of the flat. In case the Assistants turned on me again. If they are turning on me, and it’s not me doing it to myself.

Don’t think about it.

As I wait for everyone else to arrive, I stare at some luridly antique prints on the panelled pub wall. They show famous executions in the area, men hanging from gibbets, cheering crowds. One of the hangings seems to be taking place on top of Primrose Hill. Three men are dangling in a row, barefoot and dancing, grasping at the noose, obviously dying. The engraver has gone to great lengths to get the details of the throttled faces right: the boggling eyes, the protruding tongues, the gruesomely happy, popcorn-munching reactions of the audience.

My research hasn’t told me this. Primrose Hill was a place of execution? The dying, horrified face of the man on the left, apparently biting his own tongue off, as he is slowly asphyxiated, stares directly at me. Right at me. Like it knows. He knows. Who knows?

I am not my father.

Am I? I remember my dad before he lost himself: he was extrovert, full of humour. A frustrated artist who ended up imprisoned in minor accountancy: so he lived, and found joy, through his family. Dad was always ready to have fun, to make me laugh, to chase me round the apple tree pretending he couldn’t catch me. I called him the Ticklemonster and he called me Jo the Go because I could run so fast. He liked to play with words, he liked to play with life. So perhaps I take after him rather than my cautious, conservative mother. Which says?

My anxious, fumbling thoughts – ready to plunge into something worse – are interrupted.

Arlo is at the bar. He gazes at me, blankly confident, arrogantly possessive. I am in his bar. His local. To celebrate the return of my friend, my flatmate. Why did we have to come here?