Agatha Christie: A Life in Theatre

Agatha Christie on the set of Witness for the Prosecution (1953).

‘Agatha has the gift of doing what all women want to do, but only men have the chance. She achieves something. Men climb Everest, race fast cars, invent atom bombs, fight wars, become famous surgeons and man lifeboats. In her heart every woman, too, would like to do these things. But all we can do is dream. It is all we can do. It’s a man’s world. The only consolation I get is that Agatha kills off a few of you.’

Margaret Lockwood

17 January 1954

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published 2018

First published as Curtain Up 2015

Text © Julius Green 2015, 2018

Agatha Christie archive papers © Christie Archive Trust 2015

Agatha Christie quotations © Agatha Christie Limited 2015

Agatha Christie® Poirot® Marple® and the Agatha Christie signature are registered trademarks of Agatha Christie Limited in the UK and elsewhere. All rights reserved.

www.agathachristie.com

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Photographs courtesy of The Christie Archive Trust, The Shubert Archive, The University of Bristol Theatre Collection, The National Portrait Gallery, The Peter Saunders Archive, The Museum of the City of New York Theatre Collection, The Theatre Royal Bath Archive and Getty Images.

Julius Green asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007546961

Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780007546954

Version: 2018-02-21

Dedication

To Dianne

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

A Note from the Author

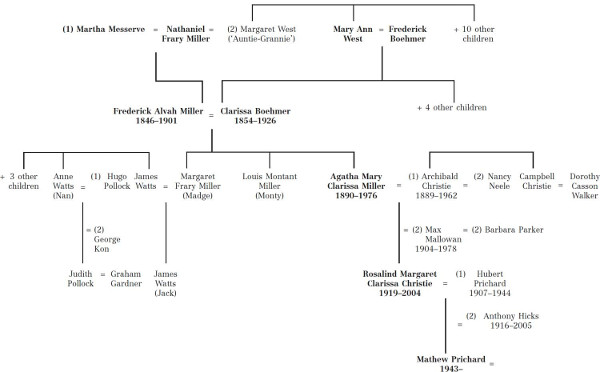

Agatha Christie’s Family Tree

Behind the Scenes

Act One: The People’s Playwright

Scene One: The Early Plays

Scene Two: Poirot Takes the Stage

Scene Three: Stranger and Stranger

Scene Four: Broadway Bound

Scene Five: Towards Zero

Act Two: Saunders Saves the Day

Scene One: The Binkie Effect

Scene Two: The Disappearing Director

Scene Three: Saunders’ Folly

Scene Four: Hat-Trick

Scene Five: The Late Plays

Curtain Call

Picture Section

Endnotes

Bibliography

Index of Agatha Christie Works

General Index

Acknowledgements

Mousetrap Theatre Projects

About the Author

About the Publisher

Foreword

A couple of years ago, my friend Julius Green came to see me looking unusually nervous! He said he wanted to write an important history of my grandmother Agatha Christie’s plays and asked if I would give my approval. I did so immediately, because I knew of Julius’ huge knowledge about her plays, and the admiration and passion he had for them. I remembered when we shuttled back and forth on a train to Westcliff-on-Sea in 2001, when Julius organised a festival of all her plays, which was not only a huge success but became a piece of history in itself. Recalling that time, and Julius’s long involvement with the Agatha Christie Theatre Company, I knew I could rely on him to be the right man for the job.

But then there was something more. Although my grandmother wrote plays before the 1950s, the great explosion of interest that occurred around the time of the opening of The Mousetrap and her other successes coincided with the period in my childhood when I spent the most time with her, and became aware what a star she was (even though she hated people saying that!). Therefore nobody could appreciate more than I do how much of a contribution her dramatic output made to her unrivalled reputation, and I am delighted to have in Julius’s book such a fitting tribute to the genius of Agatha Christie as a playwright to help balance her better known achievements as an author.

In addition, I was fascinated by Julius’s insight into the theatrical history of the period, to learn of the forthright personalities of the major players, and to read how my grandmother coped so calmly whilst all around her were living their theatrical lives.

All in all, a real treat for everybody!

MATHEW PRICHARD

June 2015

A Note from the Author

Given the quantity of published and unpublished material that is quoted in this book, I have decided to standardise various elements of it in order to assist the reader. This includes the layout of playscripts and the style in which the titles of works are expressed: in italics if quoting from a publication and not so if quoting from correspondence. My own occasional comments in the midst of quoted material are indicated by [square brackets]. Minor spelling and typographical errors in original documents have been corrected unless I believe them to be of interest, in which case they are indicated with (sic). Documents quoted in this book which date from before the 1950s tend to refer to what we now call the director of a play as the ‘producer’ and what we now call the producer as the ‘manager’. In such cases I have included a clarification. A number of Agatha Christie’s plays underwent changes of title; where this occurred, the title used in this book is that of the particular draft, production or published edition being discussed.

Agatha Christie’s Family Tree

Behind the Scenes

This is the story of the most successful female playwright of all time. She also wrote some books.

Agatha Christie (1890–1976) is universally acknowledged as the world’s best-selling novelist, and yet the significance of her contribution to theatre has been largely overlooked by historians. This despite the fact that she is responsible for a repertoire of work that enjoyed enormous global success in her own lifetime and continues to do so more than forty years after her death. She not only holds the record for the world’s longest-running theatrical production, but is also the only female playwright to have had three of her works running in the West End simultaneously. Her first attempts at playwriting date from around 1908 and her last completed play premiered in 1972. Nine of her plays opened in the West End in the 1940s and 1950s alone, and two of them were big hits on Broadway. For Christie, theatrical success arrived relatively late in life; it brought her much pleasure and, despite her legendary shyness, she enjoyed the company of theatrical people and relished their eccentricities.

From the point where she finally broke through as a playwright in the 1950s, it is clear that Christie continued to regard writing books as her day job, but that she found true creative fulfilment in her work for the stage. In her autobiography she notes:

Of course I knew that writing books was my steady, solid profession. I could go on inventing plots and writing my books until I went gaga … writing plays seemed to me entrancing simply because it wasn’t my job, because I hadn’t got the feeling that I had to think of a play – I only had to write the play that I was already thinking of. Plays are much easier to write than books, because you can see them in your mind’s eye, you are not hampered by all the description that clogs you so terribly in a book and stops you getting on with what’s happening. The circumscribed limits of the stage simplify things for you. You don’t have to follow the heroine up and down the stairs, or out to the tennis lawn and back, thinking thoughts that have to be described. You only have what can be seen and heard and done to deal with. Looking and listening and feeling is what you have to deal with.1

In a 1951 article on Christie, The Stage newspaper reported that she found writing plays easier than writing books because ‘With a play you can go straight to your plot and characters and you have not to deal with the problem of describing scenes and the movements and habits of people. If you are at all successful, all this appears automatically through your characters and the action in which they are involved.’2 And, in an interview for the BBC Radio Light Programme in 1955, she once again stated that ‘Of course writing plays is much more fun than writing books … you must write pretty fast, keep in the mood and keep the talk flowing naturally.’3

Some commentators have interpreted such remarks as implying that, whilst writing books was Agatha Christie’s profession, writing plays was simply her hobby. My own view is that, for a writer who had a real aptitude for dialogue and who, by her own admission, felt hampered by ‘description’, playwriting was her true vocation. And her determined, twenty-year struggle to gain recognition as a dramatist bears witness to this. Like most playwrights, Agatha Christie has her good and her bad days but, speaking as a theatre practitioner rather than an academic, it seems to me that she is both a master of her craft and a unique and witty voice with a great deal to say about the human condition. Actors always seem to enjoy engaging with her characters and find much in them to relate to, belying the popular misconception that they are thinly drawn caricatures. Her work is laced, whether consciously or not, with echoes of the other great playwrights of the era, and some of the most celebrated actors of the day appeared in her plays.

So why has history been so unkind to Agatha Christie, playwright? At the height of her popularity in the 1950s the dominant producing force in the West End was Binkie Beaumont, but Christie’s most enduring working relationship was with Peter Saunders, a rival impresario who was openly critical of the monopolistic tendencies of the Beaumont empire. So, despite her popular success, Christie was notable for working outside the established (and at times fearsomely ruthless) West End oligarchy of the day; a fact that makes her achievements all the more remarkable. As a doyenne of the ‘well-made play’ she remained delightfully untouched by the Royal Court revolution and consequently does not even feature in the vocabulary of those academics for whom the history of twentieth-century British playwriting started with Look Back In Anger in 1956. She thus occupies a unique position as a playwright, outside both the prevailing theatrical culture and its counter-culture; and her theatrical vocabulary suits the historians of neither.

Another very straightforward reason for the neglect of Christie as a playwright is continued confusion over the authorship of the plays credited to her. As well as her own work for the stage there have been a number of second-rate adaptations of her novels by third parties; and this, combined with the enduring success of third-party film and television adaptations, has led to an assumption that the plays credited to her were not from her own pen. There is an immediate and obvious qualitative difference between Christie’s own work for the stage and that of her adaptors, but the staging of a number of such works in her own lifetime, and several more since, has inevitably diluted her own stock as a playwright. Christie herself was unequivocal on the subject, repeatedly expressing her displeasure at her stage adaptors’ work: ‘Several books of mine were dramatised by other people and they all dissatisfied me intensely,’ she told the Sunday Times in 1961.4 Ironically, though, whilst arguably initially hindering her own development as a playwright, the adaptors’ efforts provided her with an entrée to the world of theatre and its practitioners, where she became a willing student and gained the confidence to promote her own work: ‘I think what started me off was my annoyance over people adapting my books for the stage in a way I disliked.’5 Certainly, she is the only playwright I can think of whose reputation has had to contend with the truly bizarre obstacle of a body of work for the stage penned by others but promoted to the public and the critics in her name.

And then there is the question of collaboration. Playwriting is often a shared undertaking, and writers from Shakespeare to Brecht to David Edgar have worked with others in the preparation of their scripts. There can be no doubt that one of the things that most attracted Christie to the stage was the collaborative nature of the process, enabling her as it did to exchange ideas with others in a way that her largely solitary work as a novelist did not. She was a willing and adept participant in script discussions, either as a commentator on other people’s adaptations of her novels or as a playwright herself attempting to address the concerns of producers, directors and actors. Despite the patronising claims of certain directors about the level of their own input, the fourteen full-length plays and three one-act plays that were premiered on stage in Christie’s lifetime, and which carry her name as sole playwright, are indisputably her own work. She only ever incorporated the suggestions of others up to a point, and always remained in control of the script development process. And when she was convinced that she was in the right she was legendarily immovable. Ironically, her own highly accomplished adaptation of one of her short stories was appropriated wholesale by an ‘adaptor’ without so much as an acknowledgement of her own dramatisation as source material. And, conversely, she had very little to do with the only script for which she is actually credited as co-adaptor. In such cases Christie herself acted in good faith at the behest of agents and producers, but it doesn’t help when it comes to establishing the extent of her own contribution to the dramatic canon that bears her name.

There is also perhaps a misconception that Christie exploited her reputation as a novelist to promote her career in the theatre, and that her theatrical successes were in some way dependent on the success of her books. If anything, as we shall see, the opposite was the case, and the expectations raised by the popularity of her detective fiction frequently hampered her progress as a playwright and prejudiced critical opinion against her work on the stage. Whilst her producers inevitably attempted to capitalise on her existing fan base, the adaptations of some of her best-selling novels proved to be critical and box office disasters, and theatregoers repeatedly demonstrated themselves to be more than capable of judging her work for the stage on its own merits. Christie’s success as a playwright was exceptionally hard-won and, far from resting on her laurels as a popular novelist, she consistently dedicated herself to honing her craft, observing and willingly learning from the numerous leading theatrical practitioners with whom she worked. In any case, Christie was writing at a time when combining careers as a novelist and a playwright was not uncommon; amongst the contemporary female playwrights who did so were Clemence Dane, Margaret Kennedy, Enid Bagnold, Dodie Smith and Daphne du Maurier. Christie was simply both a more successful novelist and, ultimately, a more successful playwright than any of them. And, for those who carp that her plays were simply adaptations of existing works, it is instructive to note how far these adaptations diverge from their source material and that, amongst her full-length plays, there are nine totally original works, six of which were premiered in her lifetime. Christie herself said, ‘I prefer to write a play as a play, that is rather than to adapt a book.’6

Christie was passionate about theatre and was deeply involved in the processes of making it. She attended and contributed to rehearsals, and her delightful ‘author’s notes’ at the front of some of the published editions of the plays show her engaging with everything from the mechanics of creating the effect of a lift ascending and descending in Appointment with Death to the problems associated with the unusually large dramatis personae of Witness for the Prosecution and the ‘ageing’ of actors and multiple locations in Go Back for Murder. She was very aware of the practicalities of putting on a play, favouring single sets and relatively small casts (Appointment with Death and Witness for the Prosecution are notable exceptions), and this partly accounts for her enduring popularity with cash-strapped repertory theatres and touring companies over the years, and the consequent law of diminishing returns in terms of both production values and credibility within the theatre community.

Born in 1890, for the first ten years of her life Agatha was a Victorian; Gladstone became Prime Minister for the fourth time shortly before her first birthday. As a teenager and a young woman she was an Edwardian. She waved husbands off to both world wars, and women got the vote on the same basis as men when she was thirty-eight. In 1969 she watched man land on the moon on television, and when she died in 1976, Harold Wilson was Prime Minister. Her first success as a novelist came when she was thirty; but although she started writing plays as a teenager, none of her work was staged until she was forty, and her playwriting career didn’t really take off until she was in her sixties. This is an interesting inversion of the timeline of Noël Coward’s career; Coward and Christie were contemporaries, but his success as a playwright came much earlier in life and reached its pinnacle in the Second World War with Blithe Spirit and Present Laughter, just as Christie was experiencing her first West End hit with Ten Little Niggers. (The history of this play’s problematic title is examined later in this book.)

All but one of Christie’s plays are firmly set in the period in which they were written, and they resist any attempt at updating in just the same way that the work of Noël Coward does. Although the moral dilemmas faced by the characters and their guilt, obsession, love and jealousy are timeless, their behaviour and interactions are very much a function of the social mores of the time in which each play is set; not to mention the fact that modern communications technology would severely compromise key elements of the plotting. The stakes are raised in several of the storylines by the ever-present threat of the hangman’s noose; particularly in Verdict, where the existence of the death penalty clearly informs the protagonist’s decision not to turn the murderer over to the police, and in Towards Zero, where it accounts for an extraordinary plot twist. The acceptability of smoking provides a continuous subtext of cigarettes, pipes and cigars both as a form of social interaction (offering someone a cigarette can be as good as a chat-up line) and to underscore key moments of tension. A nervous character will reach for a cigarette and a pipe smoker is usually to be trusted.

But it would be a mistake to assume that the society reflected in the majority of Christie’s stage work is a halcyon one of pre-war vicarage tea parties. Ironically, this relatively elderly woman, whose upbringing was defined by the mores of the previous century and whose frame of reference is generally assumed to be that of the pre-war era, found lasting fame as a playwright in the decade when ‘angry young men’ were allegedly redefining the theatrical playing field at the Royal Court. Christie did not live a cocooned middle-class life. She was adventurous, widely travelled and politically aware, and encountered people of all classes and cultures. She worked in a hospital dispensary during the First World War (gaining a comprehensive knowledge of poisons in the process), was one of the first people to surf standing up on a surfboard (whilst visiting South Africa) and made use of recent changes in the law to divorce her cheating first husband, Archie Christie, in 1928. Her work spans a century of massive social and political change and this does not go unacknowledged within it, from The Hollow with its crumbling aristocracy facing up to the loss of empire to the overtly political challenge to the conservative orthodoxy represented by Alderman Higgs in Appointment with Death, the ‘not a Red, just pale pink’ Miss Casewell in The Mousetrap, the post-war suspicion of foreigners in Witness for the Prosecution and the persecuted East European immigrants at the centre of Verdict.

Whilst the received wisdom is that Christie’s novels are to a certain extent formulaic, and much scholarly time has been devoted to analysing these alleged formulae, the same most definitely cannot be said of her work as a playwright, and it almost seems that she found herself enjoying greater freedom of expression as a writer in this genre. A repertoire encompassing the edge-of-your-seat chiller Ten Little Niggers, the definitive courtroom drama Witness for the Prosecution, the Rattiganesque psychological drama Verdict and the ‘time play’ Go Back for Murder can hardly be described as formulaic and there is no such thing as a ‘typical’ Agatha Christie play. Despite the enduring perception of her work as little more than an extended game of Cluedo, Christie’s plays tend to be character-led rather than plot-led, and she clearly relishes entrusting the entire momentum of the story-telling to the voices of her ever-colourful dramatis personae. Her dialogue fairly trips off the tongue and is spiced with witticisms and observational comedy frequently worthy of Wilde. In her plays the detectives and police inspectors are usually relegated to minor roles, with the solving of a crime taking second place to the human drama that is being played out. It is as if we come closer to what Christie wants to say as a writer without the dominating presence of Poirot and Marple. With the exception of Poirot’s appearance in Black Coffee, the first play of hers to be produced (in 1930), neither character features in any of her own stage plays, and indeed she removed Poirot from the storyline when undertaking her own adaptations of four of the novels in which he appears, maintaining, doubtless correctly, that he would pull focus on stage.