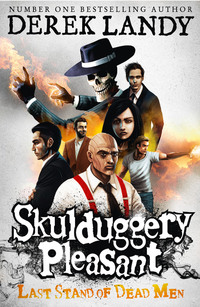

Last Stand of Dead Men

“Witches and Warlocks get along like a house on fire,” he said. He was wearing the grey suit he’d been in the last time she’d seen him. His hat was on the table in the corner, and the lamplight flickered off his skull. “You shop at the same stores, use the same recipes … If anyone would have heard what the Warlocks are up to, it’d be a witch.”

“Maybe those other witches,” Dubhóg said, somewhat resentfully. “Maybe the Maidens or those Brides of Blood Tears with their exposed bellies and their veils and their long legs … Is my belly exposed, Mr Skeleton? Am I wearing a veil? Are my legs long and shapely?”

“Uh,” said Skulduggery.

“There are different sorts of witches and Warlocks,” Dubhóg continued, “just like there are different sorts of sorcerers. There are male witches and female witches, just as there are male Warlocks and female Warlocks. There are all kinds. But we keep to ourselves. The business of others does not interest us.”

“But the business of others does interest me,” Skulduggery said. “I’ve been hearing rumours, Dubhóg. Disquieting rumours. I just thought you might be able to allay my fears.”

“And that is why you attacked me?”

“I merely knocked on your front door.”

“Then you attacked my door.” Dubhóg squinted at him. “You think you’re so clever, don’t you? With your Sanctuaries and your rules. You think everyone should be like you. Well, I’m not like you. Witches aren’t like you. Warlocks aren’t like you. Why would we want to be? You live your lives restricted by rules. Even your magic is restricted. Sorcerers treat magic like science. It’s disgusting and unnatural. It twists what true magic is all about.”

“Control is important.”

“Why? Why is it important? Magic should be allowed to flourish in whichever form it takes.”

“That way madness lies.”

“For the weak-minded, perhaps.”

“Tell me what Charivari is up to.”

“I wouldn’t know,” said Dubhóg. “I’ve never met the man. Why would you think I know anything about any of this?”

“A little over a year ago, you were seen talking to a Warlock who went on to try to kill me and my associate.”

“A year? How can I be expected to remember that far back? I’m eight hundred years old. I get confused about the little things – who said what, who did what, who tried to kill who … My days are devoted to my granddaughter and my nights are spent making multiple trips to the toilet. I don’t have time for anyone’s grand schemes.”

“So Charivari has a grand scheme?”

Dubhóg frowned. “I didn’t say that.”

“Actually, you sort of did.”

“Oh, I see,” said Dubhóg. “You’re one of those, are you? You like to play around with words to try and get the better of me. Well, it’s not going to work. With age comes wisdom, you ever hear that?”

“I did, but I’ve found that wisdom has a cut-off point of around one hundred and twenty years. Once you reach that, you’re really as wise as you’re going to get.”

“Well, I’m wise enough to say nothing more on the subject.”

“So you know more on the subject.”

“I didn’t say that.”

“Again, you implied that you did. The Warlock you spoke to had been hired by the Necromancers to kill us – he said he owed them a special favour. Why?”

Dubhóg shrugged. “Why does anyone do anything?”

“What did the Necromancers do for the Warlocks? Did they give them something? They did? What was it – an item, an object, a person? Was it a thing, was it information, was it—? It was information? OK.”

Dubhóg stepped back, horrified. “What are you doing? Are you reading my mind? No one can read my mind. Witches’ minds cannot be read.”

“I’m not reading your mind,” Skulduggery said. “I’m reading your face. What information did the Necromancers give them? A strategy? A place? A name?”

Dubhóg screamed and covered her face with her hands.

“A name, then,” Skulduggery said.

“You don’t know that!” Dubhóg cried. “I have my face covered!”

“So that’s what the Warlock wanted from the Necromancers, but what did he want from you? This will go easier for you if you just tell me what I want to know.”

“Never!”

While Dubhóg reeled dramatically with her face covered, Valkyrie stepped out from hiding and approached the circle. Skulduggery gave her a little wave. She could have wet her finger and smudged the chalk, but instead she decided to put all those hours of practice to good use. Crouching by the edge of the circle, she put her hand flat on the ground and pushed her magic into the concrete until she was almost part of it, until she was cold and hard just like it was. And then she wrenched her hand to the side and the ground cracked, splitting one of the lines of chalk.

Dubhóg whirled at the noise, and stared at Valkyrie as Skulduggery stepped out of the circle. “How did you get in? Did you harm my granddaughter?”

“She’s fine,” Valkyrie said, straightening up.

“If you hurt her …”

“We didn’t.”

Dubhóg’s face contorted in fury. “You will pay!”

“I told you,” Valkyrie said, frowning, “we didn’t hurt—”

But it was too late.

Dubhóg flew into the air, the space around her crackling with an energy that made her long hair stand on end. She hovered there, looking like an electrocuted cartoon character, her face twisted in anger. Gracious leaped at her, and a stream of sizzling light caught him in the chest and sent him hurtling backwards. Donegan rushed in, his hands lighting up, but Dubhóg caught the energy stream he sent her way and responded with another one of her own. The air rushed in around Valkyrie and she shot towards Dubhóg, the shadows bunching round her fist. Dubhóg grabbed her by the throat, her grip strong, and Valkyrie clicked her fingers, summoning a ball of flame into her hand, and prepared to ram it into the witch’s face.

“Granny,” Misery called. “Granny, stop that. Gran. NANA!”

The battle froze, and Dubhóg looked round. “Misery? You’re OK?”

“They didn’t hurt me, Nana,” Misery said, somewhat crossly. “Now put her down before you embarrass me even more.”

Dubhóg drifted to the ground and let go of Valkyrie, who stepped back, rubbing her throat.

“Terribly sorry,” Dubhóg said, her hair returning to normal, that ferocious power leaving her as quickly as it had arrived.

“That’s quite all right,” Skulduggery said, walking forward. “We all make mistakes, isn’t that right? No harm done.”

In the corner, Gracious moaned.

“Tell them what they want to know,” Misery said, “then come upstairs. I’ll put the kettle on.”

Misery turned, walked away, and Dubhóg cleared her throat and smiled at Skulduggery.

“I’m a constant source of embarrassment to her,” she explained. “I can’t do anything right, really. All I want to do is protect her from the everyday cruelties of life, but I always do something wrong. I say the wrong thing, or I attack the wrong people …”

“Kids,” Skulduggery said, sympathising.

“She’ll miss me when I’m gone,” Dubhóg said.

“So, the Warlock …”

“Oh, yes, him. I don’t know what information the Necromancers gave him. He mentioned he’d been talking to one of them, a man with a ridiculous name.”

“Bison Dragonclaw,” said Valkyrie.

“Dragonclaw, yes,” said Dubhóg. “That was it.”

“And why did he come to see you in the first place?” Skulduggery asked.

“He thought I’d be able to convince my sisters to join with Charivari. But we Crones use magic differently from even other witches – it doesn’t keep us so young. We are old women, and so I told him no.”

“Join Charivari to do what? What are the Warlocks planning?”

“War,” said Dubhóg. “They’re planning on going to war.”

The last few days he’d spent at his old shop in Dublin, working on various items of clothing. Repairing, modifying, making from scratch. He had been content there. Happy. Alone with this thoughts, alone with the needle and thread, with the fabrics, his mind had been allowed to settle, and it had been wonderful.

But his vacation was over, and here he was, being driven back into the squalid, bleak little town of Roarhaven and all that anxiety he’d left behind was quickly building up again inside his chest. They drove through Main Street, drawing a few cold glances from the townspeople. There was a single, sad little tree planted in a square of earth on the pavement. For as long as he’d been here, he had never seen it with leaves. Here they were in August and it was just as thin and skeletal as it had been in winter. It wasn’t dead, though. It was as if the town were keeping it alive purely to prolong its torture.

They approached the dark, stagnant lake and the squat building that rested beside it, all grey and concrete and uninspiring. The Administrator, Tipstaff, was waiting for him as he thanked the driver and got out of the car.

“Elder Bespoke, welcome back. The meeting is about to start.”

Ghastly frowned at him. “It’s not scheduled till two. They arrived early?”

“In their words, they are ‘eager to negotiate’.”

Ghastly walked out of the warm sun into the chill Sanctuary, Tipstaff beside him. “Who’s here?”

“Elder Illori Reticent of the English Sanctuary plus two associates, an Elemental and an Energy-Thrower.”

“That’s all?”

“We’ve been tracking them since they flew in this morning, and we’ve been keeping an eye on all known foreign sorcerers in the country. It would appear that these three are the only ones in the vicinity. Elder Bespoke?”

Tipstaff held a door open and Ghastly grumbled, but went inside. In here, his robe was waiting. He pulled it on, checked himself in the mirror. His shirt, his waistcoat, his tie, his trousers, all those clothes he’d made himself, all of them were covered up by this robe. His physique, honed by countless hours of punching bags and punching people, was rendered irrelevant by this shapeless curtain he now wore. The only thing that wasn’t covered up was the one thing he’d spent his life trying to draw attention away from – the perfectly symmetrical scars that covered his entire head.

Tipstaff brushed a speck of lint from Ghastly’s shoulder, and nodded approvingly. “This way, sir.”

Ghastly could have walked to the conference room blindfolded, but he let Tipstaff take the lead. There was Ghastly’s way of doing things and there was the proper way of doing things, and if there was one thing Tipstaff liked, it was procedure.

They reached a set of double doors guarded by two Cleavers. At Tipstaff’s nod, the warriors in grey banged their scythes on the floor in perfect unison and the doors opened. Tipstaff stood to one side as Ghastly walked in.

Grand Mage Erskine Ravel sat at the round table and scratched at his neck. The robes could be particularly itchy against bare skin, which was why Ghastly had lined his with silk. He hadn’t offered to line Ravel’s, though. He found it quietly amusing to watch his friend suffer.

Beside Ravel sat Madame Mist, her face covered by that black veil she always wore. He’d often wondered if her features were as unsightly as his own, but decided that no, the veil was probably some piece of tradition that the Children of the Spider had chosen to keep alive.

Across from Ravel and Mist, Illori Reticent sat patiently. A pretty woman with a beautiful mind, Illori’s smile grew warm when she saw him.

“Elder Bespoke,” she said, rising to meet him, “so good to see you again.”

“Elder Reticent,” said Ghastly, shaking her hand. “Sorry I’m late.”

“You’re not late, we’re early, which in some circumstances can be twice as rude as being late.”

Ghastly glanced at the man and woman standing behind her, their backs to the wall and their expressions vacant. “You only came with two bodyguards, I see.”

“Of course,” Illori said, smiling innocently. “I’m not in any danger, am I? I am among friends, yes?”

“Indeed you are,” said Ghastly, smiling back at her. “It’s nice that you remember. So many of your fellow mages seem to have forgotten that fact.”

“Well, they’re not here, and I am, so I have been granted the honour of speaking for the whole of the Supreme Council. And I have some things I’d like to discuss with you.”

“Then let’s get started,” Ghastly said, and took up his place at Ravel’s side.

Illori looked at them all before speaking again. “The Irish Sanctuary has been at the forefront of the battle against oppression and tyranny for the last six hundred years, ever since Mevolent’s rise to power. We recognise that, and we appreciate that. Until recently, your Council of Elders was the most respected Council of any territory in living memory.”

Ravel nodded. “Until recently.”

“That’s no secret, surely. The death of Eachan Meritorious was a great loss to us all, but for Ireland it signalled the beginning of a rapid slide into uncertainty, aided no doubt when Thurid Guild’s brief time as Grand Mage ended with his imprisonment. Again and again, the Irish Sanctuary has been battered by enemies from without and within.”

“And again and again we have triumphed,” said Ghastly.

“Indeed you have,” said Illori, “thanks to some exemplary work by your operatives. But your Sanctuary has been weakened. When the next attack comes, you may not be strong enough to prevail. So I have come to you with a solution, should you be agreeable.”

“This’ll be interesting,” Ravel muttered.

“Before the Sanctuaries, there were communities. Each of these communities was ruled by twelve village Elders. Each of these twelve would oversee a different aspect of village life, but, when the time came to make important decisions, all twelve votes were counted equally.”

“We know our own history,” said Ravel. “We also know that when the Sanctuaries were established, the unwieldy twelve was cut down to a more practical three. Even the communities that are around today haven’t kept up with the old ways.”

“Even so,” Illori said, “lessons can be learned. We propose the establishment of a supporting Council of nine – five mages of our choosing, four of yours – to help you in the running of your affairs. This would leave you with a majority of seven to five, and it would mean you had more sorcerers, more Cleavers, and more resources. Your Sanctuary would remain under your full control and it would be returned to its former strength.”

Ravel looked at her. “I’m curious as to why you think we would possibly say yes to this.”

“Because it’s a fair proposal. You retain full control—”

“We retain full control now,” said Mist. “Why would we change?”

“Because the current situation is not acceptable.”

“To you,” said Ravel.

“To us, yes,” said Illori. “There are members of the Supreme Council who view you as dangerous and reckless and they continually call for action against you. Every mage paying attention is expecting war to break out at any moment. Why would you risk hostilities if the situation can be resolved amicably?”

“There’s not going to be a supporting Council, Elder Reticent.”

“Why not?”

“Because the Supreme Council does not tell us what to do.”

Illori shook her head. “Is that what this is? A matter of pride? You won’t accept our terms because you don’t like being told what to do? Pride is wasted breath, Grand Mage Ravel. Pride is you putting your own petty concerns over the well-being of every sorcerer in your Sanctuary. More than that, it’s putting your petty concerns over the well-being of every mortal around the world. If war breaks out, it’s going to be so much harder to keep our activities off the news channels. If that happens, it’s on your heads. But we can avoid it all if you’d just listen to reason.”

“The Supreme Council has no right to dictate to other Sanctuaries how to conduct their business,” said Mist. “In fact, the Supreme Council itself may even be an illegal organisation.”

“Ridiculous.”

“We have our people looking into it,” Mist said.

“Don’t bother,” said Illori. “We’ve already had our own experts combing through the literature. There is no ancient rule or obscure law that says Sanctuaries cannot join forces to combat a significant threat. It’s what we did against Mevolent, after all.”

“We are a significant threat, are we?” asked Ravel.

“You might be,” Illori answered, then shook her head. “Listen, I didn’t come here to threaten you. We are standing on the precipice and the Supreme Council isn’t going to back away. They’re angry and they’re frightened, and the more they think about this, the more angry and frightened they become. They’re hurtling towards war and you’re the only ones who can stop them.”

“By agreeing to their demands.”

“Yes.”

“We’re not going to do that, Illori.”

“Do you want war, Erskine? Do you actually want to fight? How many of us do you want to kill?”

“If you’re looking to calm things down, calm down those making all the noise. We will not be intimidated and we will not be bullied.”

Illori laughed without humour. “You keep painting yourselves as the aggrieved, like you were just minding your own business and then the Supreme Council came along and tried to steal your lunch money. You are at fault, Erskine. Your Sanctuary is weak. You’ve made mistakes. We are not the bad guys here. We have gone out of our way to treat you with respect. We released Dexter Vex and his little group of thieves, didn’t we?”

“What does that have to do with us?” asked Ghastly. “Vex’s little group of thieves, as you call it, consisted of three Irishmen, an Englishman, an American and an African. It was an international group affiliated with no particular Sanctuary, who sought approval from no one before embarking on their mission.”

“An international group that was led by Dexter Vex and Saracen Rue,” Illori said, “two of your fellow Dead Men. They may not have told you what they were planning, but where would they have brought the God-Killer weapons had they succeeded in stealing them, except back to you?”

“Vex wanted them stockpiled in order to fight Darquesse.”

“A more suspicious mind than mine might wonder if Darquesse was merely the excuse he needed.”

“All of this is a moot point,” Ravel said. “Tanith Low and her band of criminals got to the God-Killers before Vex and she had them destroyed.”

“And you had her,” said Mist. “Briefly.”

“What was that?” Illori asked.

“You arrested her,” said Mist. “The woman who assassinated Grand Mage Strom. You arrested her, chained her up, and she escaped.”

“What’s your point?”

“There are those who say Strom’s assassination was the breaking point,” said Mist. “It was his death that has propelled us to the verge of war. He was assassinated here, of course, in this very building. For this, you blame us, even though Tanith Low is a Londoner. But when you finally arrest Miss Low, when you have the chance to punish the killer herself for the crime she committed … she mysteriously escapes.”

“Are you saying we let that happen?”

“It has allowed you to refocus your blame on us, has it not?”

“I haven’t heard anything so stupid in a long time,” said Illori, “and I’ve heard a lot of stupid things lately. We don’t know how she escaped or who helped her. The investigation is ongoing. There are those in the Supreme Council, by the way, who think this Sanctuary had something to do with it.”

“Of course they do,” Ravel said, sounding tired.

“They believe both Vex’s group and Tanith Low’s gang were taking orders from you,” Illori said. “Two teams going after the same prizes, independent of each other – doubling the chances of success.”

“Well,” said Ghastly, “it’s nice to see the Supreme Council thinks we’re so badly co-ordinated as to organise something as incredibly inept as that.”

“Illori, go home,” Ravel said gently. “Tell them you approached us with this proposal and we politely declined. Tell the Supreme Council that, before he died, Grand Mage Strom agreed that their interference was not necessary. He would have recommended no further action if Tanith Low hadn’t killed him. You and your colleagues have nothing to fear from us.”

“But that’s not strictly true, is it?” Illori asked. “You have the Accelerator. We’ve heard what it can do. Bernard Sult witnessed its potential. He saw the levels to which it can boost a sorcerer’s power. If you so wanted, you could boost the magic of every one of your mages and you could send them against us. Our superior numbers would mean nothing against power like that.”

“That’s not something we’re planning on doing.”

“Then dismantle it. I’m sure that would go a long way to placating the Supreme Council.”

Ravel shook his head. “The Accelerator is powering a specially-built prison cell – the only cell in existence capable of holding someone of Darquesse’s strength. We need it active.”

“Then give it to us as a gesture of good faith.”

“As a gesture of naivety, you mean. We’re not giving you the Accelerator. We’re not dismantling it. We’re not turning it off. We’re not even sure if it can be turned off. If that makes the Supreme Council nervous, then that is unfortunate. Please make it clear to your colleagues that we do not intend to use the Accelerator against them as part of any pre-emptive strike.” Ravel sat forward. “If, however, the Supreme Council launches any kind of attack against us or our operatives, and if we feel significantly threatened, then using the Accelerator to even the odds is always an option.”

“They’re not going to be pleased to hear that.”

“Illori, at this point? I really don’t give a damn.”

Her mum and baby sister clapped and Valkyrie sat back down, grinning. Faint trails of smoke rose, twisting, from eighteen candles, and were quickly dispersed by her mother’s waving hand.

“Did you make a wish?” her dad asked.

She nodded. “World peace.”

He made a face. “Really? World peace? Not a jetpack? I would have wished for a jetpack.”

“You always wish for a jetpack,” her mum said, cutting the cake. “Have you got one yet?”

“No,” he said, “but you need to use up a lot of wishes to get something like a jetpack. On my next birthday, I’ll have wished for it forty times. Forty. I’ll have to get one then. Imagine it, Steph – I’ll be the only dad in town with his own jetpack …”

“Yeah,” she said slowly, “I’ll be ever so proud …”

Her mum passed out the plates, then stood and tapped her fork against a glass. “I’d like to make a toast, before we begin.”

“Toast,” said Alice.

“Thank you, Alice. Today is a big day for our little Stephanie. It’s been a big week, actually, with the exam results and the college offers. We’ve always been proud of you, and now we’re delighted beyond belief that the rest of the world will be able to see you the way we see you – as a strong, intelligent, beautiful young woman who can do whatever she puts her mind to.”