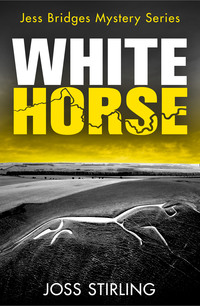

A Jess Bridges Mystery

A man strolled in from the far end, holding a bone-china mug of coffee. Leo could at once see the strong family resemblance to his brother, though Roger Chamberlain was clean-shaven with white hair slicked back from a high forehead.

‘Why are you making that racket, Madeleine?’ he asked, rather rudely considering there was a stranger present.

She waved her car keys in Leo’s direction. ‘The police. An Inspector George. He wants a word.’

Leo discounted the idea they would offer him refreshments even though he had been up since the early hours and could do with a coffee. ‘Major Chamberlain, Mrs Chamberlain, as you may have heard, there’s been a serious incident on White Horse Hill last night. The body of a young woman was discovered there near to dawn. As a result, we are conducting house-to-house enquiries in Kingston Beauchamp today. So far, the victim hasn’t been identified and we are asking locals if they know her, either as someone who lives round here or because they may have seen her yesterday as she passed through the village on the way to the hill.’ Leo watched them both for a response but got nothing. Not even a ‘how did she die?’

‘What’s this to do with us?’ was what the major did ask.

Leo concluded then that if the National Trust brother, Andrew, were an Old Testament prophet, Roger was more like a New Testament Pontius Pilate, ready to wash his hands of any problematic business. ‘We are seeking to identify her. We won’t know if she connects to you until we know who she is.’

‘Connects to us? How could she?’ Mrs Chamberlain sounded put out by the very suggestion. Apparently, to be found dead on the White Horse was enough to suggest you weren’t one of their type.

‘There are many possibilities. She could be the daughter of one of your neighbours, for example, or someone you recognise from a local shop. I take it you don’t have a daughter yourself?’

‘Of course we do. Two. Iona, whom I saw just this morning, and Ella.’

‘Is Ella here?’ If the parents refused to be helpful, perhaps the daughters would be better subjects for his questions.

‘Obviously not. She’s in South Africa on her gap year.’

And how was Leo supposed to have known that? ‘The girl might be one of your daughters’ acquaintances, someone you would know by sight.’ He was hesitant to show them the same photo he had showed the brother. It sounded very unlikely it was either of their girls – surely the uncle would’ve identified her? – but he couldn’t be certain of that. The warden had just glanced at the image and the girl’s eyes were shut.

‘Describe her,’ rapped out the major, as if Leo were some junior officer reporting to him.

‘I have an image I could show you. It’s of the body so I will understand if you’d prefer not to see it.’

‘Too right I’d prefer not to see it. Had enough of that in the army. Describe her. Distinguishing features and whatnot.’

Leo gave them a brief summary: age, height, likely weight, colouring …

‘Very blonde hair, you say?’ interrupted the major, showing his first spark of interest. ‘It’s not us you want then; it’s my tenant at the manor. He surrounds himself with blondes.’

‘Awful man,’ muttered Madeleine.

‘But he pays up on time. That’s more than I can say for that friend of yours from Cheltenham.’

Before they launched into a domestic argument, Leo tried to get the interview back on track. ‘And what is your tenant’s name?’

‘On the lease he’s down as Terence O’Brien, but in his little commune of nubile beauties, he’s known as Father Oak.’ Was that an envious glint in the major’s eye?

‘Father Oak?’

Major Chamberlain snorted. ‘Exactly. He’s got some New Age scam running, a sort of commune thing. Druidic and Karma Sutra hotchpotch. But as everyone appears above the age of consent and they keep the grounds beautifully, I say “live and let live”.’

Madeleine rounded on Leo with her steely glare, standing shoulder to shoulder with her husband. She acted as if the policeman had taken issue with their choice of tenant. ‘It’s a free country, Inspector.’

That was not a matter that Leo felt he needed to weigh in on. It was a much more complex question than that throwaway comment suggested. He glanced down at the notes he had taken. ‘To sum up, you don’t know any young women locally with strikingly blonde hair, apart from the ones living in your manor?’

‘I wouldn’t say we know those women either. We are aware of them,’ corrected the major.

‘Did either of you notice any strange activity around the village last night? Anyone heading up the hill to either Wayland’s Smithy or the White Horse?’

‘We played bridge here with the Frazers last night. We didn’t go out, did we, Madeleine?’

‘Exactly. So we can be of no further use to you. Really, Inspector, I have to go.’ Madeleine gave Leo a chilly nod as she passed him on her way to the car.

There was something Leo wanted to look at more closely before he left. He needed just a moment alone. ‘Do you have a contact number for your tenant, Major Chamberlain?’

‘In my files.’ His gaze slid past Leo to latch onto the screen where a race was just lining up in the starting gates, the horses shying and bucking.

‘I’d be very grateful if you could dig that out.’ Leo gave no sign of moving. If the major wanted to catch that race, his quickest route to doing so was by giving the policeman what he wanted.

With a huff, he gave in. ‘One moment then.’

As he disappeared back through the door through which he had entered, Leo moved closer to the grand piano with its collection of family photos in silver frames. The Chamberlains were pictured in variations of the same pose with their two girls, shown at different ages. The older one had dark hair and the younger fair; there appeared to be at least a ten-year age gap between them. The pictures went all the way up from infancy to the early twenties and thirties of the pair. The most recent image showed a smiling young woman in a bridesmaid’s dress of gold silk. She stood alongside the dark-haired bride in the doorway of what Leo recognised as the local church, St Martin’s. The groom wasn’t present for that moment, or if he had been, then he’d been cropped out. The bridesmaid wore a garland of wild flowers woven with corn, giving the impression of being gold all over. Her hair rippled forward over her shoulders. She was quite stunning, even putting her attractive sister in the shade. Unfortunately, she also looked disconcertingly like the victim, though her hair was wavy rather than straight and perhaps a shade darker.

‘They’re my daughters, Inspector. Ella. Iona.’ Roger handed Leo a Post-it with a number written on it. ‘That’s Iona’s wedding earlier this year.’

‘You’re sure Ella is in South Africa?’ Leo asked.

He immediately returned to the defensive. ‘Do you think I don’t know where my own daughter is?’

‘You wouldn’t be the first parent to lose track of the whereabouts of their grown-up children.’

‘Well, I haven’t. Goodbye, Inspector.’ And very firmly, he showed Leo to the door.

Leo wasn’t going to give up so easily. Something about this couple got under his skin and made him want to dig in his heels. ‘Does Iona live locally?’ Leo asked on the threshold, thinking that if the father wouldn’t answer questions then maybe the oldest daughter would.

‘Yes.’

It was like getting blood from a stone. ‘And where can I find her?’

‘At the vicarage. She’s the rector here.’

Leo felt as if he’d missed a step. That hadn’t come up in the searches. ‘I see.’

For the first time, the major revealed a glimpse of a deeply-buried sense of humour. ‘That’s what I thought at first. Now I’m used to it. Not that either Madeleine or I are God-botherers ourselves. But if you’d seen Iona at nineteen, you wouldn’t have expected her to seek ordination a decade later.’

Naturally, the local vicar was on the list of people to interview. This was all useful stuff. Leo felt a little less resentful of their stiff-necked reception. He gave the most persistent of the beagles another pat as a peace offering.

‘Thank you, Major.’

There was no ‘good luck with your enquiries’ or anything like that. Roger simply shut the door and went back to watch the three o’clock at Newmarket.

They were an odd couple. Leo tried and failed to imagine what growing up in that household had been like. They almost made him thankful for his own dysfunctional mother. At least he had never doubted that she was human.

***

St Martin’s was bathed in the glow of honeyed autumn light as Leo approached the main doors. It was a blocky chalk building with a square tower topped by a pitched grey roof. You could feel the Anglo-Saxon roots here; no fancy Gothic flourishes or Norman excesses. Former parishioners lay in neat rows, many headstones leaning in the same slightly drunken orientation away from the building, like they were straining to look up to the tower. The door was open, so Leo went inside.

‘Hello?’

The nave was very narrow, with no side aisles. A cold white light gave it an underwater feel, like he had plunged into the Arctic ocean. On the whitewashed walls were the usual tributes to past squires and ladies, but at the altar end a local artist of not-so-many generations ago had been let loose. Under the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites, they had left a fabulous frieze of red vines with hanging grapes, which stood out starkly against the creamy plaster. The vines curled up either side of the choir towards a painting of two blue-clad angels kneeling above the altar. It was an unexpected jewel. For Leo, this was a little slice of heaven. An urge just to sit down and take it in stole over him. He wished he could let the tendrils curl around him and root him to the spot.

‘Magnificent, isn’t it?’ The rector approached from behind, a pumpkin embraced in her arms to add to the harvest display that was accumulating by the altar. Less polished today than in her wedding photo, she was still an attractive woman with her bob of dark hair and large hazel eyes. Leo imagined they were around the same age, mid-thirties, the see-saw point between youth and middle age. It was odd to think of someone of his own generation being a vicar. He had always pictured priests to be old men in faded cassocks. The Reverend Iona had surprised him a little by wearing denim and a fleece, just like his friends would.

‘Iona Chamberlain?’

‘Chamberlain-Turner.’ She lodged the pumpkin on a pew and offered her hand. ‘Couldn’t just take my husband’s name as it would sound like a boast.’

It took Leo a moment to compute. I own a Turner.

‘I don’t know what my parents were thinking. At least Jimmy isn’t a Bucket or a Stamp.’ She gestured to a couple of the memorials which were indeed in those names. ‘Could be worse.’

Leo chuckled. ‘I met your parents earlier. We’re making house-to-house enquiries.’

‘And you’ve made your way from the house of Chamberlain to the house of God? Fair enough.’ She literally invited Leo to take a pew. ‘I suppose this is about the poor girl found up on the Downs. How can I help?’ Unlike her mother, this sounded a genuine offer.

‘You’ve heard already?’

‘I’m the vicar; of course I’ve heard.’ She smiled slightly. ‘First port of call for any trouble.’

‘Really?’

‘I had my uncle who you met earlier in here in a state, telling me about it but swearing me to secrecy until you’ve made an official statement. Poor Uncle Andrew, he doesn’t deal well with stress.’

‘He said he didn’t recognise the victim, so I was wondering if you’d be willing to look at a photo of her?’ Leo explained that it was postmortem, but that didn’t seem to faze her. He supposed that vicars, like policemen, must see a lot of dead people as part of their job consoling the grieving.

‘Let’s have a look.’

Leo felt he had to say something before she did that. ‘I did notice that she bore some resemblance to your sister … from the family photos.’

‘Ella? Oh, Ella’s in South Africa.’

‘So your parents said.’ Leo held out the screen, but watched her face carefully. ‘Do you know who she is?’

The shock was instant. ‘I … I … no, it can’t be.’ She shook her head and took the phone from him to enlarge the picture so she could see the features in greater detail. ‘Oh my God. Ella? No. It has to be someone who looks very like her. The hair’s wrong – too short, too straight, too fair.’ She was grasping at straws of hope.

‘Is there any way of checking if Ella is really in South Africa? Just to rule her out?’ Leo asked gently.

Iona rested her head on her arms supported by the pew in front. ‘It’s just the shock. Sorry, what did you ask? Ella? Oh, no – at least, not easily. She’s working at an orphanage way out in the wilds. No phone reception and only intermittent emails.’

Leo’s unease grew with each of these admissions. ‘Does your sister have any distinguishing features? A scar or a tattoo maybe?’

‘Aside from her hair? She has her tramp stamp.’ Iona blinked like an owl dragged into daylight. ‘Never told our parents. It’s vine leaves, like these ones in the sanctuary, but in the shape of angel wings. Designed it herself. She’s clever that way. There’s a tattoo artist in the next village who does them; it’s a kind of cottage industry.’

Leo sent a quick text to the pathologist. ‘OK, I’ll get that checked out. Can I get someone for you while we wait?’

Having taken her moment, Iona was now rallying. ‘It’s fine. Just a superficial likeness. Has to be. God, I’ve been missing her. I’m seeing her everywhere.’

‘How long’s she been gone?’

‘Flew in and out again for my wedding, which was about four months ago. I didn’t really see her properly. You know how it is; you don’t get to talk to anyone at your own wedding. Too busy.’

He didn’t actually know, never having been married. ‘And the last message?’

‘Two weeks ago. Just the usual “I’m fine, how are you?”’

‘Any photos? News about her work?’

Iona shook her head. ‘One thing to understand about Ella is that she doesn’t like any of us knowing what she’s up to. I only know about the tattoo because of the fittings for her bridesmaid’s dress.’

Leo got an instant reply back from Gerry.

No tattoo on back. One on shoulder. Heart made of two entwined flowers. Sweet peas.

Some of his tension unwound.

‘I’ve had confirmation. Nothing on the lower back of our victim.’

‘Good. I mean, not good, obviously. Someone is still dead.’

‘I know what you meant.’

‘Just had a bad moment there.’ Iona braced herself. ‘OK, I’m back online. Do you have any more questions for me?’

‘I’m afraid so. Were you here last night?’

She grimaced. ‘I suppose you have to ask everyone for their alibi, don’t you? I was. I began decorating for Harvest Festival with a few of my local ladies. I can give you their names. I find I quite like doing that kind of thing. The artistic challenge of it.’

‘What time did you leave the church?’

‘About nine. Went straight home.’

‘Where’s the rectory?’

‘It’s not the draughty old house next to the church, if that’s what you’re asking. The church sold that years back. The Frazers live there now. Bankers.’ She shrugged, in an accepting way. ‘We’ve a new house in a little development on the edge of the village near the river. Much easier to heat.’

That was on the opposite side of Kingston Beauchamp from the hill.

‘How did you get there?’

‘Drove. I was ferrying fruit and veg all evening. Normally I’d walk or cycle.’

‘Did you notice any unusual traffic, or anything out of place?’

‘Nothing out of the ordinary. The pub was busy. It’s a popular place. We get a lot of outsiders passing through. I guess that’s what she was, poor girl. I was tucked up with my husband by nine-thirty. Neither of us went out again. We’re watching a box set about drug lords for relaxation.’ She laughed at herself. ‘I know; that sounds wrong.’

‘Sounds pretty normal to me. Your parents suggested that if I were looking for young, fair-haired women I should try the manor and someone called Father Oak.’

‘Terry O’Brien? I suppose that makes sense. He does love to surround himself with girls of that kind.’ She now looked sad and weighed down by care – not the result of Leo’s questions but something more permanent, he would guess. ‘What do you see around here, Inspector?’ She gestured to the church.

‘Really, I’m not sure …’

‘Please. Humour me.’

‘I see a gem of a building, a sense of ages past.’

‘That’s what visitors expect and it’s what they get if they drop in for a few minutes. But the truth is far different if you stay for more than an hour or two. You haven’t asked me why I came back to minister here.’

‘I assumed to be near your parents?’

She gave a hollow laugh. ‘You didn’t spend long with them then? No, not that. They would much prefer me to have stayed in Cambridge where I trained. That at least sounded respectable, serving from a distance. They weren’t happy when I felt called back here.’

‘So what called you?’

‘There’s a battle here. I saw it as a child.’

‘A battle?’

‘Against the forces of darkness.’

And he had been liking her so much … ‘Right.’

‘You’re not a man of faith, Inspector?’

‘I’m not much of a joiner. I keep my views to myself.’

‘Yes, I can see that.’ And Leo felt uncomfortably that she did see him rather too clearly. ‘I’m a moderate person. I don’t have the fire of a martyr like St Martin.’ She smiled self-deprecatingly. ‘But I do believe that some people, some places, are given over to evil. Surely as a policeman you must come across that?’

‘In the people, yes, maybe. Some killers are sick or inadequate, but some you come across for whom there is no explanation or excuse. But places? No, they’re just that: places. Not good or bad unless we make them so.’

‘I think I would’ve agreed if I hadn’t lived here all my life. This place is just difficult. St Martin’s is the single beacon of light in the village – or I try to make it so. I’ve got other parishes in my care, other churches, but this one is far and away the most challenging spiritually. It might look like a postcard, but something is wrong here.’

‘What kind of wrong?’

She rubbed her face, looking almost sheepish. ‘God, I just know that you’re going to hate what I say next.’

‘Try me. I’ve just come from a murder scene. I might be more sympathetic than you expect.’

She still feared his scepticism. ‘I know it’s a lot for a logical person to believe, but there is a spiritual war being waged here. I don’t know if it comes from inside a person, or if they open themselves to something out there, but it’s real. For the moment, the darkness is winning, and has been for centuries.’

It was relevant that he was dealing with a ceremonial killing. There had to be others around who took their twisted version of religion seriously if they were murdering for it. Iona might know something that would help him, names even of people involved in the rituals. ‘And do you have a source for this darkness, a name or names?’

‘No single source. It’s just outside the door – in the people who live here, the woods, the stones and the rivers. It looks very ordinary but this place does extraordinarily wrong things, and makes me very aware of my own failings.’ She rose to her feet. ‘But, speaking more practically for your purposes, I would say starting with O’Brien would be a good way to go.’

He got up from the pew. ‘Thank you. That’s most helpful.’

She walked with him to the door, something she doubtless did for many visitors who crossed this threshold in all stages of hope and despair. ‘Mind how you go, Inspector.’

He lifted a hand in acknowledgement as he headed out.

‘I mean that sincerely. Watch your back. This isn’t a place you can trust.’

He left her in the doorway where she had stood for the wedding photo with her sister. Only now did he notice the wreath of plaited straw with corn dollies hanging over the lintel. The straw girls, held by threads around their necks, swayed in the wind like bells.

Chapter 6

Jess

I hated myself. And I hated – what was it? – Prosecco mixed with gin and tonic. And maybe a martini … or two?

I knew before I started drinking that I would feel like this the next day, but did that stop me? Did it hell! And now I was paying the piper. I just wished he’d stop blowing his bloody bagpipes in my skull.

Oh no, not pipes. That was the calming ‘you’re about to take off and possibly crash and die’ music airlines think will get us in the right mood for the short play they do on each flight. Why do they like to remind us of all the horrific possibilities? Before they told me, I hadn’t been thinking of running for the nearest emergency exit, asphyxiating as the air fails, getting lost at sea with just a little light on my life jacket to show rescuers where I was. Now I could think of nothing else, apart from my throbbing head, that was.

Michael considered my condition amusing. I remembered that I hated him too and told him so.

‘No, you don’t,’ he said, adjusting the window blind for this short flight back to London. ‘I got you extra legroom.’

It was the case that, as Michael’s plus one, I got to sit next to him on the row at the front. His wheelchair had been stowed in the hold and he had travelled here via a combination of airport golf cart and crutches. I wasn’t much help as I’d felt like throwing up during the transfer. I thought the aircrew had me down as a complete waste of space and a failure as a companion – both of which were true.

By the time we were airborne and I’d downed a bottle of water and a couple of painkillers, I was feeling a little more human. Michael noticed.

‘Tanglewood is in 8A,’ he told me, prodding me with the cheery disaster leaflet from the seat pocket. ‘There’s an empty seat next to her if you’re up for a conversation.’

Oh yes, the lost-but-not-missing daughter. It would at least distract me from the dull pain behind my eyes.

Once the seatbelt light was switched off, I headed down the aisle before the drinks cart could mow me down.

‘May I join you?’ I asked Tanglewood.

The fat guy (sorry, but it’s true) in the aisle seat was none too pleased that I squeezed past him and forced his pudge back onto his side of the armrest. They really should sell seats on width as well as legroom.

‘How are you feeling?’ asked Tanglewood.

‘Like I should’ve listened to my good angel last night, but it’s always the little demon on my other shoulder that seems to have the most fun. She made me do it.’

‘You are looking a little pale.’

‘Pale and interesting, I hope?’

‘Pale and close to vomiting.’

I leant back and closed my eyes. ‘Sadly, that’s accurate but I can manage if you just tell me what I need to know. I’ll listen even if I don’t say much.’

The drinks cart caught up with us and Tanglewood ordered a Bloody Mary. ‘Can I get you anything, Jess?’

‘A tranquilliser gun, loaded for a rhino?’ I suggested. Sleep would be good right now.

‘I don’t think they stock those.’

‘Ginger beer then.’ I was hoping that would settle my stomach.

Once our drinks were balanced on her tray table, she began her story. I rested my head and tried to concentrate.

‘Lisette is my only child. I was last with her two years ago after she graduated. Then, she was twenty-one, bright, passionate about the environment … a joy to behold. She said she was looking for somewhere to put her energy. I made all of those motherly suggestions – graduate training schemes, working for an environmental charity, even VSO, but none of that was what Lisette White wanted. No thank you, Mother. Now she’s twenty-three and hates me; she cut off all contact.’