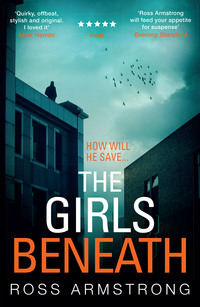

The Girls Beneath

‘Do you think your dad’s… a little hard on him?’ I say, searching for the most delicate way to put it.

‘Dad’s no soft touch. Never thumped me. But then Eli is… Eli.’

‘Eli? Eli!’ I call, seeing his face peeking out unsubtly behind the kitchen door.

Before Eli drags his bones towards me, Dom hangs his head and then whispers to me, ‘Sorry, Tom. He’s having trouble at school, they’re pulling him into some gang. It’s nasty. He asked if he could hide out here.’

As he enters, I see the picture of a kid stuck between the devil and the deep blue sea. Shitty dad at home. Shittier kids at school.

Eli clearly isn’t ill and I have a choice to make. He’s breached his contract and I’ve stumbled in on him doing it. Let him have it and dad will come down hard on him. But at least a full blown ASBO would give him a legitimate reason to stay away from his new friends in the evening.

One thing’s for sure, Eli is getting fucked from every side whatever I do. He’s contributed pretty amply himself, yet I know I could save him some hassle if I just look the other way on this occasion.

But this is my first week, so I keep it simple and I call it in.

Later, he’ll say I was ‘victimising him’.

And what’s true is, I could’ve been kinder. I think they call it tough love. I hope, in that tiny moment of decision, that everyone else isn’t too tough on him as a result.

*

It’s been a week. I can’t quite tell what sort yet. But it’s certainly been a week. Friday has come shaped like mercy.

*

‘Dee. Dah dah dah dee dah, dah dah, dah dee…’

I get these tunes in my head sometimes, I think everyone does it.

Earworms. People say you choose the tune because the lyrics associated hold the key to something you’re mulling over in your subconscious.

But I don’t know about that.

I barely even remember the words. I try to keep it down as I zone out, muttering under my breath as I walk.

‘Dee. Dah dah da, dee dah, dah dah, dah dee…’

I get a call on my radio about a minor accident at the other end of the main road. I need to go and direct traffic. I’m not sure this is what I was birthed for.

At least you can pick your hours, within reason. You have to cover thirty-seven in a week and they like you to take one evening. So I went for a five-hour evening shift on Thursdays, seven till midnight. Then took eight hours on all the other weekdays, leaving my weekend free. I consider the merits of this time format. Even my thoughts start to bore me.

I count them as they as they plod through me. Dry and empty.

This is a thought.

This is a thought.

This is a thought.

Then one comes along covered in this morning’s regrets:

I was called to a house after a neighbour had complained about frequent raised voices and commotion, as well as the sound of skin on skin contact and not the friendly kind. I didn’t bother the neighbour on the right side of the house before calling on the home in question. They had been brave enough to make the call and I didn’t want to give them away by paying them a needless visit first.

As I approached, the neighbour on the left side came out, and when she saw me she hustled back inside quickly. She had a look of intense fear about her. I wondered if that came from the build-up of what she was probably also hearing through the walls, night after night. A man, taking out his stresses on his wife. Or whoever else.

The neighbour looked spooked so I didn’t say a word. She didn’t want any trouble, and to her maybe I meant trouble, so she shot back inside to avoid whatever was about to happen. She gave me a funny feeling, her presence sparking a strange sensation close to déjà vu.

When he answered the door, the man, bald, moustached and laying on the innocent look as thick as it comes, led me inside, where a woman, presumably his wife, sat in the kitchen giving little away.

An extraordinary sense of creeping unease came over me, a tingling on my skin, which had started when I saw that neighbour’s face.

I asked the woman if she was okay. I asked him the same. They both replied with a nod. It felt like something hung in the air between us that I wasn’t allowed to touch. There seemed to be a palpable prompt the scene itself was giving me, other than the possible violence between them. Another cue that I wasn’t picking up on.

The silent couple… The noises through the wall… That neighbour’s face.

‘There’ve been reports of a disturbance coming from this residence. I’m duty bound to follow that up. So… anything I need to know?’

Nothing but the shaking of heads.

‘Anything at all?’

In the next deafening silence, I tried to communicate to her wordlessly that she didn’t have to take any shit. And to him that if he was doing something to her then I’d be back with uniformed friends and trouble. But all I said was:

‘Well, we’re a phone call away.’

I shook off the tingle and reluctantly got out of there, resolving to do the only things I could: make peace with my limitations, and with the sour fact that she would probably never make that call, and record the encounter in my pocket notebook.

I can feel my mind listlessly erasing the encounter, as I make my trudge through grey reality towards traffic duty.

But then, they’ve recently found you can’t erase memories. They’re physical things. They make visible changes to the brain. Some are hard to access if you haven’t exercised them recently, but they never disappear. If you took my brain out of its case, you could see it all.

• There’s the crease that holds my parents’ smiles at my fifth birthday party.

• There’s the blot that is my first crush’s face.

• There’s that neighbour’s face, just next to it.

• There’s the dot of possible heroism. Watch me be disheartened, watch it degrade and fade.

This is not the electrode up my arse my life needed. This isn’t even a power trip. Perhaps I should have stuck with charity fundraising on the phones, say my thoughts. But I guess mum and dad would be prouder of me doing this.

The radio kicks in.

‘PCSO Mondrian? This is Duty Officer Levine, over.’

‘Yeah. Yes, this is me.’

‘… You’re supposed to say over.’

‘Over,’ I monotone.

‘So when someone calls for you, say go ahead, over. Over.’

‘Go ahead, over.’

‘Understood? Over.’

‘Yep.’

A pause. I wait.

‘Don’t say yes, say affirmative. And you didn’t say over. Over.’

I sigh, away from the walkie-talkie. Then steel myself.

‘This is PCSO Tom Mondrian. Affirmative. Go ahead. Over.’

‘Understood. Hearing you loud and clear. I’m over by the loos, over.’

‘Understood… over.’

‘What a wanker,’ I mutter to myself.

Cccchhhhhh...

‘And after you’ve finished speaking, take your finger off the PTT button. We all heard that.’

Crackles of laughter from someone else on the line.

‘You forgot to say over, over,’ I say.

I remember to take my finger off the button this time as I walk along.

‘Not funny, over,’ he says.

But it was a bit.

Levine is clearly the pedant of the bunch. I keep walking, my feet crunching in the snow.

Here we are. Broken glass on the tarmac. Red faced fella at the side of the road. A light blue Astra with one door open, diagonally up the kerb. Levine sees me and holds up a hand. His posture says, ‘I’ve got this thing locked down, you just stand way over there.’

La-di-dah. The beat goes on.

The ABC. The body. The beat. All firsts.

I wonder if anyone has ever fallen asleep while directing traffic. Could be another first for me this week.

I check my watch and see there’s an hour until my week ends. Nearly time to head back to the station locker room, change, clock off. Maybe a drink with the team if I’m unlucky.

Levine signals me to allow traffic around the car from my side, while he holds vehicles at a stand at his end for a while.

I signal. I smile courteously at the drivers as I do so. La-di-da.

I see many faces I recognise.

Amit from the paper shop down the road. Zoe Hughes from Maths drives past, averting her eyes to ignore my existence. She didn’t always.

I glance to the cluster of shifty kids on the other side of the road to make sure they see traffic is being held and let through at intervals. I’m only looking out for them, but they take one covert glance at me, put up their hoods and scarper off, one holding something weighty in a black plastic bag that’s got them pretty excited.

I probably should be curious about what it is, but that’s not really very me.

‘Dee. Dah dah dah dee dah, dah dah, dah dee…’

I stop the flow. I can barely see the driver in front of me through his tinted windscreen. But I squint to get a look at him in there and see his outline change. He taps the wheel, jittery, maybe coked up, which would account for the nerves. But I’m not going to create any extra trouble for myself. He glares at me, stiller now, as I hold my ground, letting him know I know there’s something up.

Then I wave him through. He shoots away hastily, as I snigger, enjoying my power to intimidate. Then I move to the side of the road, making sure I’m still visible to passing traffic.

Blue car. Red car. White car. Mini. Bus… Bus…

Oh!

I feel tired. Not just tired, faint. I shake my head. Somewhere I hear the bus stop but I don’t see anything. It’s darker now, all around me. I feel sick. I’m fighting to keep my eyes open. I try to go to ground, layer by layer, as a tower block might be detonated or dismantled.

I feel like I’m going to vomit but I don’t want to in front of all these people. It’s a shame-based reflex. I try to hold it in. I try to hold it together. There are shouts behind me.

The sound of footsteps. Running. I just need to reach the floor and everything will be okay. But my ears are going crazy horse. A high-pitched squeamish noise. A fresh white blah blah blah. Like TV failure.

Nearly at the ground now. It all flashes. I swallow ocean breaths. I wonder whether I’m causing scenes. My hands reach for the tarmac black. That high pitched squeal blazes on.

The world looks like it’s under a slow strobe.

Then my back is against the kerb. Clouds forming, crowd forming. I know something is wrong for sure.

I pull out my phone and try and call the… or should I use my… what’s the number for the 999…

I stare at the phone. Not fainting yet. Holding on.

Its numbers are strange. Just lines. Like Greek, or Latin. Symbols I don’t understand. I comprehend nothing.

My head is wet with something. But I don’t know what. I see Levine running up to me. I’m not sure whose blood this is.

I shout to him to check everything is all right.

‘Take the hard road up.’

I don’t know why that comes out. It’s not what I intended.

I try again. As I crawl towards him, off the pavement and onto the road.

‘Perhaps the hard road’s impossible!’ I shout as I crawl and my hand drags past more wet.

‘Take the hard road up. Anything is possible!’ I shout.

It doesn’t feel like my voice. He’s nearly with me. I see the bus has emptied and its passengers are looking at it. And me.

It’s slow motion. It’s hard tarmac broken glass music video inner city incident news commercial heartache.

That high-pitched squeal sings on and on.

A song from a passing car radio strikes up.

‘We lived in this crooked old house

some cops came over to check it out

left on the step was a little baby boy

In a soft red quilt, with a rattle and a toy.’

My hands shake beneath me like an engine does before it stalls. A guy with a busted tooth shouts something.

Before my head falls, I notice the bus has two broken windows. One on each side.

They’re all on their phones. It’s a picture that blurs.

My ears still work though. Listening to the radio song.

‘You’re my little one

Say I didn’t love in vain

Please quit crying honey

Cos it sounds like a hurricane’

I wonder how those windows got broken.

That’s my last thought for now. Before I go.

It’s just one of those things.

Some days you meet the person you were always meant to be with.

Some days you get shot in the head.

4

‘‘Can’t get that, dah dee dah, dah dah, my head…’

‘Good. You’re awake. Looking good,’ says the voice.

Male. Warm. My thoughts run slowly like traffic jammed cars. His face comes into view.

I’m cold. I guess I should do something. Say something maybe. Missed it. The chance has come and gone.

We sit in silence for a while. Everything has changed.

‘Cold,’ I say, trying to get things moving, in my head.

‘Oh yes. It is a little chilly.’ He turns and nods to someone. He smiles. I lift my head to see who he’s looking at, but by the time I do they’re gone.

Where am I? A hospital. I guess.

‘How’s it all feeling?’ says the man.

‘Unsure,’ I say.

‘You’re unsure how you feel? Or you feel unsure?’

‘The second one.’

‘That’s understandable. Any pain?’

‘A little in the head.’

‘Also understandable, that’s just swelling in the cranium.’

‘What’s the… chrysanthemum?’

‘It’s a flower that blooms in Autumn, but that’s not important right now. Your mental lexicon is still recovering, which I’d expect. Say after me, cranium.’

‘Cramiun.’

‘Good. Your skull. Your head. We had to get in there a little.’

‘In there?’

‘Yes, we had to remove the bone flap. But we replaced it. Everything went reasonably well.’

‘Re… Re… Re… Re… Reasonably?’

‘Well… your sort of accident isn’t the sort of thing one always recovers from. But things are looking up.’

I’m putting it all together again. The bus. The shattered glass. The man running towards me. A man I know?

… Doreen? … Liam … Loreen?

‘I assume you haven’t been told what’s happened to you then?’

I assume I haven’t as well.

I drifted in and out. Of the light and the grey. I don’t know what was a dream and what was… whatever this is. I’ve seen many faces hover over me. I remember being moved, I think. One second I would be one place. The next, the ceiling would tell me something else.

I realise I have no concept of how long I’ve been here. It could be weeks. Months. Longer.

‘How long?’ I say.

‘How long what?’

I struggle with the structure of the question. I feel my eyes rolling around in my head. With each tiny movement, there’s a crack of pain somewhere deep inside my thinking organ.

My eyes begin to water as I strain to process the question, to hold onto my thoughts. I make some sounds from deep within me. I breathe deep, trying to speak, but I can’t. Instead. I cry.

My nose runs. Hot tears roll down my cheeks. Big old-fashioned sobs, despite myself. I don’t feel like crying. And yet, I am crying. Every breath shudders with effort between my lungs and my mouth. I feel like a puppet controlled by an inebriate puppeteer.

My hands scramble around for a tissue. There is one next to me but it takes me an age to drag it out from its cell.

He waits, watching. Patient.

‘Tom? You asked me… how long?’

‘How long… from then… till now?’

‘Today is Sunday, you sustained the injury on Friday.’

It seems impossible. If he’d said I’d been here a year, or two, I’d have believed him. My muscles feel brown and dappled. I grapple with the controls like a madman, a blind pilot. I must be older. Two days? They have to be lying. But to what end?

It’s then that I notice there is someone else in the room, to my left. My neck turns so my head can look at him. He looks back. His face is difficult to read. He looks apprehensive. I look away and he does the same. Then I look back at him and he looks me in the eye. He says nothing. Just analyses me. He must be some underling. He’s younger than the other man. Although I couldn’t say how old the man in front of me is. My brain isn’t giving me all the answers I need yet. His voice interrupts us as I go to look at the silent man for a third time.

‘Yes, it may seem longer. That can happen. Would you say it seems longer?’

‘Yes. Yes.’

‘That’s interesting.’

He writes that down. Out of my periphery I analyse the silent man. He faces the doctor, too, not moving a muscle.

‘Do you know what happened to you, Tom?’

The question lingers in the air…

The bus. The shattered glass. The blood. The shouts. People with their phones out. I crawl across the road. I feel sick. No pain. But I feel faint. I hear a song from a nearby car radio. The man runs towards me.

‘I… I… had… a stroke?’

‘Hmm. Interesting.’

He writes that down. Then scratches his nose. He turns as a nurse comes into the room and hands me a glass of water and a pill.

I take it off her. Steadily. I look at my hand and try to will it to do my bidding. I put the pill in my mouth and force the water down the dry passage of my throat. I stare back at my hand and order it to give the nurse back the glass. When I turn back to the doctor he is checking his watch. His eyes meet mine and he smiles, sunnily, full beam.

‘Now, how long would you say that took? That little sequence of taking your pill and drinking your water.’

Is this a trick question? What is their game?

‘Ten… twenty… ten… seconds?’

He glances to the nurse.

‘That took six and half minutes. But don’t worry. I’m confident things will get easier.’

He comes a bit closer now. The man next to me does, too. It’s become intimate.

‘Tom. You were shot. In your head. Do you understand?’

I want to laugh. So I do. Ha ha ha ha ha.

There’s no gap between think and do. Ha ha ha ha ha.

The tears roll down my face again. The others stay stock still. As I laugh and cry. I don’t know why I do either of these things. My feelings fire off in all directions like stray sparks. I laugh, I wail.

Then I stop. I look at the nurse. Then at him.

‘No. I wasn’t shot. I can’t have been. It didn’t hurt. I’m alive.’

He breathes in, cautious, unsure how to put this.

‘The brain has no pain receptors. The nerves in your skin can’t react fast enough to register impact. A little bullet, at that speed… It just went in.’

‘And out…’

‘Err… no. It just went in.’

‘And you got it out?’

‘No. My God, no. Much too dangerous to move it, I’m afraid. It’s still in there, in three pieces. But don’t worry, it doesn’t pose you any danger. Think of it as a souvenir.’

He pops out a one-breath laugh and turns to the nurse for support but she doesn’t join in. When I straighten up, so does the silent man. Copying my body language is supposed to make me feel comfortable, I suppose. But he is eerie.

‘So,’ says the doctor, ‘all your vital signs are remarkably good. Another twenty-four hours of monitoring and tests, then, all being well, you’ll move from intensive care to a general ward for recovery. Then you’ll spend some time in the rehab unit, and that’ll give us an idea of what outpatient care you’ll need after we discharge you. Sound good?’

My breath rattles. I want to say things but thoughts rush at me. I grasp at consonants. I try a ‘p’, an ‘m’, an ‘n’. Then back to a ‘p’. He comes closer and puts a hand on me. I am calmed.

‘But I was shot… in the head?’ I murmur. I hear myself. I sound like a malnourished tracing.

‘Yes. But I’m confident you won’t be here too long. I think you’ll walk with a limp for a good long while and certainly a lot slower than before, for now. And so will your speech be. Slower, I mean. But you should be… next to normal, in no time. Better than normal perhaps. I look forward to seeing how it all pans out.’

He looks at me, smiling indulgently. I take a note of his features. Ogling them for what is probably five or so minutes.

He has a beard. He has small brown eyes. He is half bald. He is lightly tanned. He has soft grey hair. He has a striped blue shirt. It has a purple ink stain on it.

‘Somebody… shot me?’

‘It would appear so, yes. Now, all I’d ask of you is to take it slow. I will be with you throughout this process. You certainly don’t have to go back to work for a good long while yet. And they’ll absolutely look after you well, financially speaking, so you don’t need to worry about any of that. You were injured on duty, you’re getting the best treatment money can buy. In my opinion, ha! You shouldn’t want for anything while you recuperate. If there are abnormalities – and considering the places the bullet debris has come to rest in, there may be abnormalities – I’ll be with you every step of the way. We’re going to handle those… differences… together.’

‘Sorry. Sorry. Sorry. Why am I not dead again? Why is my head still on my shoulders? What was I shot with?’

‘Well. A gun. A sub machine gun, I’d say. But just once, so that’s good.’

‘In… in… war… in films… in war… the head means… dead.’

He’s excited by this, standing and taking his pen in his hand to gesticulate with.

‘Good question. Good cognitive reasoning. Now, I can only tell you that when you’ve seen people shot in World War whatever, or Kill whoever, or The Murder of Whichshit, the science is somewhat… bollocks. Sorry! Poppy cock, I mean to say. You do often die with a shot to the head. Very, very often. But a bullet wouldn’t really have the momentum to knock your head much to the side let alone blow it off its shoulders. Think of it this way, if a gunshot were powerful enough to throw your head back significantly, the momentum of firing it would throw the gunman back violently, too. And that’s not the sort of device that would be very viable on the mass market. What a gun is, is a compact handheld product made to eject sleek aerodynamic discharges that glide smoothly into flesh. So along with the shock and speed of the event and the way the device is engineered, of course you wouldn’t feel a thing. Which is a bit of a result in a way, isn’t it?’

I’m not sure how to feel about this statement at this point.

‘Ask us one more question for today, please. It’s very good for you to ask questions. It’s a useful process. You’re doing very well, Mr Mondrian.’

‘Will… I… get… back to normal? Normal normal? Absolute normal?’

The nurse averts her gaze. The cold room seems to get colder. He clicks his pen a couple of times and then comes further towards me, his face so calming. His rich voice echoing as if it falls all around me. He has me. I am his captive audience.

‘The brain is an incredible thing. It has helped us to achieve amazing feats. Like building aeroplanes. Performing complicated long division in our heads. Constructing the internet. So on, so forth. But do we really know how it works? Not really. I certainly don’t and I’m one of Britain’s top neurologists. Ha.’

He looks at the nurse. No laughs again. But I like him. I’m usually good for a pity laugh, but humour is difficult to muster at the moment. The cues are difficult to pick up.

I laugh, a good minute too late. The room nods patronisingly. Then the Doctor steps in again to save me.

‘So, in short, to say “I don’t know what’s going to happen” is an understatement. I mean it’s an understatement to say it’s an understatement. I mean I don’t have a single clue. I don’t even know if I don’t know! But I’ll tell you what. Whatever your brain throws at us, we’ll just work it out. Sound like a plan? It’s fair to say it’s already making adjustments.’