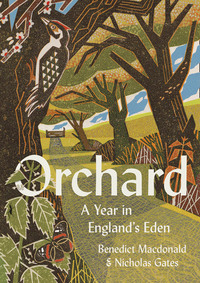

Orchard

SAXONS, MONKS AND QUEENS

‘Orchard’ originates from the Old English word, ortgeard. The first part of this word draws on the Latin hortus, meaning garden. The second part is the Old English word for yard. By the late era of Old English, the word had evolved from ‘garden yard’ to mean ‘fruit garden’.[13] And given orchards evolved so early in our history that our very language was evolving alongside them, tracing how orchards were first cultivated in Britain has greatly challenged historians.

As long ago as 854 CE, the Vale of Taunton’s Orchard Portman village was named ‘Orceard’, though this most likely referred to a general fruit-growing area.[14] The Anglo-Saxon food-rent lists, however, show little awareness or description of anything recognisable as an apple; ‘æppel’, in Old English, referred to a range of different fruits.[15]

Just after the arrival of the Normans, the Domesday Book records just one extensive apple orchard in England.[16] But now, the Normans, already familiar with the successful cultivation of apples in their own country, having inherited that in turn from fruit-growers in the Mediterranean region, would kick-start orchards as we know them today. By the late tenth century, manuscript plans of the Christ Church monastery in Canterbury show a ‘pomeranium’, or apple garden, consisting of apples and pears.[17] Pearmain, a variety of cultivated dessert apple first recorded in 1204, is the oldest cultivated apple name recorded in English.[18] By the twelfth century, Wardoun pears were being cultivated in England, at Bedfordshire’s Warden Abbey.[19]

According to orchard historian Jim Chapman, the marriage of Henry III to Eleanor of Provence led to a ‘renaissance’ in the English orchard, as the scions of culinary Cailhou pears were planted in royal gardens. Some, Jim argues, like those seeded in the Queen’s garden at Everswell, were radiant with blossom; perhaps more suited to ornament than the practical growing of fruit. It was in part from the royal court that monks such as those of Llanthony Priory received and cultivated further breeds.[20] By 1275, Battle Abbey was also selling cider to the public, and, by 1333, the poems of cleric William of Shoreham record the first known appearance of the word syder in the English language’.[21] Until their dissolution, the monasteries would continue to propagate orchards and spread them around Britain.

By the fourteenth century, the climate was changing. In a prolonged period of cooler, wetter weather, vineyards in England became increasingly unproductive for the monks, who had pioneered viticulture in many areas such as Gloucestershire during warmer, drier times. As it does today, England fell back on the easier route of importing its best wine from overseas. We began to grow apples, and orchards, in place of vines. Across the fourteenth century, orchards would continue to expand across our country.

But after the ravages of the Black Death, multiple outbreaks of the plague and the War of the Roses, apple cultivation somewhat slipped down the list of national priorities in the late fourteen and fifteen hundreds. As late as 1585, Richard Drake, a curate from the Malverns, commented that Black Worcester cultivated pears provided such poor harvest that local people were reduced to foraging wild crab apples to make perry instead.[22] The orchard’s story only picks up again with Henry VIII – and his ‘fruiterer’, Richard Harris.

THE ORCHARD EMPIRE

Henry VIII was notoriously fond of his food. In addition to the bitterns, woodcocks and wild boar that piled his plates, Henry had a sweet tooth, too. He was fond of fruits and artichokes, while Anne Boleyn was particularly partial to cherries.[23]

Henry tasked Richard Harris with no mean challenge; to scour the western world for its best fruit varieties, bring them back to England – and grow them. Close to Teynham in Kent lie the long-established fruit-growing regions known to some as ‘The Garden of England’. Here, Richard established what became known as the King’s Orchards. These were ‘mother’ orchards that would serve as the nation’s repository of world-class apple stock. Richard, it seemed, was incredibly competent. His peer, William Lambarde, noted how Richard had visited the Low Countries, bringing from there ‘cherrie grafts and Pear grafts of diverse sorts’. Lambarde also noted that ‘our honest patriote Richard Harrys planted by his great coste and rare industrie, the sweet Cherrie, the temperate pipyn, and the golden Renate’.[24] England had caught up with the Greeks and the Romans. Now, we too were rewriting Eden and creating new fruits.

From these Teynham orchards, new breeds made their way out across the country. Kent became the first county to receive and grow the ‘pippin’. This word, which sounds quintessentially English, is – we were a little sad to discover – French. Pippin means ‘seedling’. These seedlings were brought by Harris from France.[25]

Across the sixteenth and especially the seventeenth century, the overall low point for woodland cover in Britain’s history, it does seem possible that our fastest-expanding forests were orchards, as fruit-growing areas spread out from the capital of Kent. Lambarde observed that Teynham, ‘with thirty other parishes lying on each side of this porte way, and extending from Raynham to Blean Wood, be the Cherrie gardein, and Apple orcharde of Kent’.[26] Few traces can be found on modern aerial maps of this fruit forest, which would once have been greater in scale than many natural woodlands at this time. Soon, the landscapes and economies of whole counties would become shaped by the orchard. During England’s brief Commonwealth, lasting from 1649 to 1660, Oliver Cromwell decreed a national initiative to plant fruit trees across the country. While this never came to full fruition, many further orchards were planted in Herefordshire, Gloucestershire and Worcestershire.[27]

It seems extraordinary now to Nick and me, driving through Herefordshire to our adopted ancient orchard, an island of wood pasture forest in a lifeless sea of crops, that the whole of Herefordshire was once, in the words of John Evelyn, writing in 1664, ‘one entire orchard’.[28] John Beale, writing about the county in 1657, observed that ‘from the greatest persons to the poorest cottager, all habitations are encompassed with orchards and gardens; and in most places our hedges are enriched with rows of fruit trees’.[29] Herefordshire must have been quite an extraordinary place to take a horse and cart through in the seventeenth century. To see nothing but fruit forests, especially when in flower, must have been an unforgettable spectacle.

While most natural historians now recognise Herefordshire and Worcestershire as the vital last strongholds of our ancient orchards, we have forgotten that huge apple forests grew across the south-west, too, so completely have these vanished from the landscape. By the seventeenth century, Somerset was an orchard powerhouse. One hundred and fifty-six apple varieties are associated with its largely lost orchards – and the scale of these was remarkable. As late as the turn of the nineteenth century, 21,000 acres of Somerset lay under apples. Devon, at the same time, had up to 23,000 acres in all.

Cider-making, rather than the sale of apples, powered the growth of these orchard counties. By the onset of the industrial revolution, many of Britain’s older forms of farmland, such as the hay meadow, were set to vanish as agriculture started to intensify. Orchards, remaining commercially viable, adapted far better to the advent of industrial farming. New canals meant an expansion in the market for cider. By 1800, it was estimated that ten thousand hogsheads – equating to roughly five million litres of cider – were being shipped out of Worcestershire alone on an annual basis. By 1877, between the counties of Somerset, Devon, Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Gloucestershire and Kent, there were 89,000 acres of orchards.[30] Many of these had been maturing for centuries. In doing so, these new agricultural habitats would recreate something very old and special for our native wildlife.

THE NEW WILD WOOD

While forests of wild fruit trees have not been seen in most of Britain for a very long time, fossil evidence suggests that they once played a vital role in Britain’s ecological history. Aurochs (wild cattle which stood over two metres tall), wild horses, boar, elk (moose), red and roe deer would all have been shifted around the landscape by the predation pressures of brown bears, wolves and lynx. Bears, boar and horses, in particular, would have vectored the seeds of fruit trees in their dung as they moved around the landscape, planting new ‘orchards’ across the wood pastures of Britain.

Salisbury Plain is now thought to have been a landscape once dotted with vast, roaming herds of wild herbivores, such as aurochs, horses and deer. The beetle and snail fossil record suggests that this tree-studded grassland, Britain’s Serengeti, would have been dominated not by dense groves of shady trees – but by open groves of wild apples, cherries, hawthorns and sloes.[31] The name Avalon is believed to mean ‘the isle of apples’, a name given to Glastonbury’s distinctive hill in the Iron Age, when native crab-apples would have studded its steep slopes.[32]

These days, the ramshackle beauty of wild English fruit groves is now a rare sight indeed. But in the oldest pasture woods of the New Forest you can still find crab apples growing in wild formation. Here, free-roaming ponies and their foals graze gently around wild-sown fruit trees, much as their ancestral tarpan would have done eight thousand years before.

By the seventeenth century, Britain had been comprehensively deforested not over centuries but millennia – and this period marked the overall low point of woodland cover on our island. Yet with the wild wood long gone, maturing orchards – spacious wood pastures rich in vital processes of decay – would echo a lost habitat that British wildlife inherently understands. Our forgotten wood pastures, and their free-roaming wild herbivores, were given a strange reincarnation in the orchard.

Whole animal orders which had developed in old-growth wood pastures – from wood-decay beetles to woodpeckers and bats – would have found orchards a new home, and moved into them as they matured. Orchards became a unique fusion of agricultural and primeval woodland – an anachronistic refuge, surviving for centuries after the original wild wood had gone.

In addition to an orchard’s ability to mimic ancient wild habitats, if left in traditional and unfettered form, orchards act as havens of insect life. Malus apple trees have evolved enormous insect diversity over time. At least ninety-three species specialise in living in their branches. When the eminent botanist Thomas Southwood analysed the insect life of Britain’s trees, his study found that much of the apple’s richness lay in its ability to harbour tiny lives – particularly beetles, micromoths, true bugs and flowerbugs – which then build a food-chain upwards from the bottom.

Plants and lichens, many specialising in mature fruit trees, such as the orchard’s tooth fungus, harbour herbivorous insects. These in turn are followed by armies of small omnivores or predators: wasps, hornets, hoverflies and spiders – and their predators in turn. Huge reserves of saproxylic species, those specialising in dead wood, feast around old fruit trees. Delving deeper, you discover food-chains within food-chains. Mistletoe, for example, harbours the mistletoe marble moth, a specialist weevil and four other insects unique to its tenacious tangle of vegetation.

Perhaps the greatest reminder that Britain’s wildlife is intrinsically adapted to a life around ancient fruit trees is the noble chafer beetle. Now one of Britain’s rarest beetles, confined largely to traditional orchards and the ancient wood pastures of the New Forest, its larval stage occurs only within the decaying trunks of the oldest open-grown fruit trees. A whole range of other species, such as the now lost black-veined white butterfly, whose caterpillars feed on fruit trees, or the wryneck, thriving best in the lightly-grazed anthills between old orchard standards, remind us that our native ecology evolved around wild fruit trees long before people planted them here by design.

As so many wildwood species moved into orchards and flourished, our traditional orchards have become increasingly important havens, prolonging the lives of thousands of creatures that once thrived in our wooded island, millennia ago.

EDEN’S FALL

Few forms of agriculture, so beneficial to wildlife, have had such a short lifespan in our history as the orchard. Still expanding in the 1600s, less than three hundred years later orchards would begin to vanish once more. As early as the late eighteenth century, Devon and Herefordshire cider manufacture fell into decline. Canker decimated many of the trees here, but more damaging was the revelation that the contemporary method of cider manufacture was causing lead poisoning. Sales plummeted. In 1837, tariffs placed on imported fruit, which had encouraged the planting of new orchards, especially in Kent, were dropped – and the apple market collapsed. Kentish cooking apples were turned into cider, which proved of such poor quality that it led to protests.[33]

Soon, the madness of importing from overseas what we, as a country, grow best, would begin. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, two keen orchard lovers in Herefordshire, a Dr Hogg and Dr Bull, lamented how the power of steam – now fuelling trade across the sea and land alike – ‘lessens expenditure by cheapness of conveyance’. They note how ‘competition becomes world-wide … to individuals and localities the result is often ruinous’.[34] Hogg and Bull were well aware that centuries of crafting and changing apples to suit every taste and variety, and of producing a suite of fruits more varied than any we see in our supermarkets today, were coming to an end. And so they wrote an extraordinary book.

Published in 1878, the Herefordshire Pomona preserved, forever, an illustrated record of the astonishing 432 varieties of apple and pear that had, over centuries, been cultivated within the county. The lurid 3-D apples drawn by its illustrators, Alice Blanche Ellis and Edith Elizabeth Bull, still leap from the page over a century later, as if waiting keenly to be eaten. From the Sheep’s Snout to the Tom Putt, the Eggleton Styre to the Hagloe Crab, the Bastard Rough Coat to the Bloody Turk, the immensely rich culinary heritage of our orchards shines in reds, greens and yellows from every page. Yet when it comes to the wildlife that once lived in these planted wildwoods, we have often come to realise its importance long after these habitats were taken away.

Northamptonshire’s Lord Lilford, a keen naturalist, gives us some insight into the richness of his orchards around Badby, in Northamptonshire. He writes of the lesser spotted woodpecker that it is ‘certainly now the most common of our three species of woodpecker in this neighbourhood, and we have observed it in every part of the county with which we have any acquaintance’. Of the spotted flycatcher, he notes that ‘this little summer visitor is so common and so well known in our county that a very few words will suffice with regard to it’.[35]

Comparing our Malvern orchard notes to those of two centuries ago, Nick and I are struck by certain recurring stories. One of the great forefathers of modern naturalists, Gilbert White, observes of mistle thrushes that ‘the people of Hampshire and Sussex call the missel-bird the storm-cock, because it sings early in the spring in blowing showery weather; its song often commences with the year: with us it builds much in orchards’. Our notes show mistle thrushes singing by late December, and placing their first nests in mistletoe as early as February. White also describes redstarts as we have come to know them, not as birds of pure deciduous woodland, but those benefiting from the fruit-growing landscape. ‘Sitting very placidly on the top of a tree in a village, the cock sings from morning to night … and loves to build in orchards and about houses; with us he perches on the vane of a tall maypole.’ [36] One of our adopted orchard’s redstarts sings often from a hop kiln – and shows little fear of people. That there are still little windows of connection between White’s orchard and ours is quite consoling.

Some of the best natural histories of lost orchards come from the observations of Kentish naturalists, compiled in R.J. Balston’s Notes on the Birds of Kent, published in 1907. Balston describes the orchard landscape of the Kentish hills: ‘on its sides grow the best of hops and the best of orchards … It seems that birds of all descriptions could find a home to their liking upon it.’[37]

Many observations concern ‘snake birds’, which were, at this time, common across Kent’s orchards, and had been, until the mid-nineteenth century, a charismatic bird of England’s wood-pasture-dominated counties:

The well-known ‘Snake-Bird’ after its arrival becomes sparingly distributed over the county, and is generally found in the old woods and orchards, which are well stocked with old gnarled stumps and half-decayed trees, in which the bird can find holes and large cavities for a nesting place.

Known to us as the wryneck, many Kentish naturalists adopted the term ‘snake bird’ in their writings. Wrynecks, dependent on large volumes of anthills, and thus the lightest of grazing regimes by cattle, were a species that once called commonly across English orchards. Mr W.H. Power, the attentive author of ‘The Birds of Bainham’, written in 1865, observed that ‘in general [the wryneck] is to be heard all over the orchards, and I have several times, by means of a call, brought three at once into a tree within a yard of my head, where they would remain for some time, staring about in the most ludicrous manner’. [38] Today, the wryneck is vanished entirely from our country; traditional orchards one of its last strongholds in Kent – before they were grubbed away.

If wrynecks fascinated those wandering Kent’s orchards in the 1800s, other birds were considered less of a welcome arrival. Into Kent’s cherry orchards came finches by the dozen. But only one bird, the grumpy-looking hawfinch, has uniquely adapted to crack cherry kernels, with its enormously powerful secateurs of a bill. ‘Hawfinches and bullfinches have become very plentiful, and of late years the latter have become a perfect plague to the fruit growers,’ writes Balston. It seems an odd thing to imagine now, with fewer than one thousand hawfinches left in Britain, and virtually none in our orchards, that this most elusive woodland bird was once considered a pest.

Yet even the best-recorded natural history of orchards, that of the birds that once sang in The Garden of Kent, is now just that – history. The traditional, mature cherry, apple and pear orchards that once harboured wrynecks and garden warblers, hordes of marauding finches and probably far greater riches, have vanished from the map. And for all their cultural importance, and the huge areas of our country they once covered, the full natural history of orchards was never written at all.

Throughout the twentieth century, their economic output increasingly obsolete in the face of expanding cereal farms and the reduced profitability of smaller farms for cider-making, traditional orchards were grubbed relentlessly from the British countryside. Vast areas of Somerset’s orchards vanished in a tiny space of time. To this day, the distribution map shows a virtual absence of lesser spotted woodpeckers across most of its former range in the south-west. This bird, like many others, committed to orchards as a habitat far richer, more productive, than the countryside around. But when orchards vanished, the distribution of entire species shifted and reduced on a massive scale.

Since the 1950s, a further 90 per cent of traditional orchards have been lost. As with the destruction of so many other habitats, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy has hastened the demise of orchards – as it has hastened the demise of the countryside itself. Across the 1970s and ’80s in particular, many orchard owners have been paid to grub old orchards, in favour of fast-profit forms of farming.[39] Now, only a few traditional orchard landscapes remain in our country.

LAST OF THE ORCHARDS

While the People’s Trust for Endangered Species has identified 35,000 traditional orchards still growing across England,[40] the extent of these, crucial to the preservation of large wildlife populations, has dramatically withdrawn, leaving many as isolated postage stamps within a sterile wider world. When an ecosystem collapses, the fragments that remain are often too small, or scattered, to save; to remain intelligible to the wildlife that inhabited them. Only in a few tiny pockets of western England do enough traditional orchards remain for them to persist, age and grow back over the coming decades.

In Worcestershire, the Teme Valley, the Severn Vale and the Vale of Evesham retain good concentrations of traditional orchards, but those surrounding and within the Wyre Forest, benefiting from its deciduous diversity, preserve extraordinary riches. In a survey of just three traditional orchards in the Wyre, a comprehensive survey recently unearthed the existence of a staggering 1,868 species of wild plants and animals. This, in turn, was extrapolated from the examination of more than 16,000 living specimens within its confines.[41]

Herefordshire, however, remains, as it has been for centuries, Britain’s greatest orchard refuge. Distinct areas of the county act as time-capsules, not only for cider-making but the chaotic assemblage of animal life that once thrived across the county. From the meadowland orchards of Bromyard to the rich cider orchards of Much Marcle, woodpeckers and bats, owls and beetles, all thrive side by side as they once did across the whole county centuries before. But the greatest refuge of all lies elsewhere.

From Ledbury, north to the Wyre Forest, fringing the western shadow of the Malvern Hills, the satellite map clearly reveals one of the largest, most aged and most important deciduous woodlands in our country. Shamefully, it has no clear name – though it most certainly should in future years. Now unprecedented in the fractured English countryside, unbroken willow stands, oak parklands, outgrown hedges, dense deciduous copses and traditional orchards run in fine but continuous lines along the shadow of these hills for eighty kilometres. Here lies the largest concentration of traditional orchards left in Britain. And somewhere herein lies our second home.

Welcome to Orchard. It’s January. The fruits have fallen – and an army of raucous Vikings are once again rampaging across the English countryside.

JANUARY

A WORLD ON THE MOVE

NICK

Rattling around the Earth’s wide pause,

a fieldfare – tentative – adamant

… emboldened by snow-stolen fields.

NICOLA HEALEY

An acerbic easterly tries to claw its way inside my gaiters. I’m glad to have opted for ski socks this morning; the seasonal ‘Beast from the East’ is due to arrive any day. Either side of the exposed footpath lie hundreds of acres of arable farmland – cloaked in a thick hoarfrost. It’s an unforgiving landscape. At this time of year, the open ground offers little of value to wildlife seeking food and shelter. There are sometimes roe deer, and even the occasional hare, but even they can’t brave such brutal conditions. Eden lies just a quarter of a mile ahead, but you’d be forgiven for not believing that if you were standing here.