Just Before I Died

He comes over and puts a protective arm around my shoulders. And I feel an urge to sink into those arms, forever. My big husband, the National Park Ranger, the guy who rescues drowning tourists from quarries.

But no. Stiffening myself, I ease out of the hug. I mustn’t admit to my stirring feelings of disintegration, my fear of stones and brushes and dead animals. I’ve got to stay sane and sensible. Because, if they take my driving licence away it could permanently fracture my marriage, and really drive me over the edge. A few weeks of reliance on Adam, for transport, left us bickering. What would a year do? We can’t move back to Princetown, we all hate it. And park rangers are obliged to live within the Park. And Lyla has to live in the wilds, she loves it here, she hated it in town.

Without a car each, we’d be screwed.

‘All right,’ I say, forcing a smile. The way my daughter forces a smile, because sometimes she doesn’t know how to smile. ‘I’ll answer questions. I’ve got some of my own, I think.’

‘Good,’ says Adam, backing away. ‘I’ll take Lyla to school.’

The door opens and closes. I hear the rumble of the Land Rover, fading away.

Recalling my manners, I offer Tessa some tea. She nods and says sorry, again, and I feel my hostility melt, somewhat. She is a good friend, or at least one of my few remaining friends, of any kind. She gave us good advice on Lyla. When I was wondering if we should have her assessed, but Adam was more reluctant.

The fat brown teapot is placed on the kitchen table. ‘Can I ask you some general questions first, Kath?’

‘I suppose so. OK.’

‘Would you say you are happy, or were happy, before the … accident? Happy in your life, that kind of thing?’

I look her in the eyes. Startled. ‘You really think that’s a general question?’

She lowers her gaze, apologetically. ‘OK, but this is tricky. Let’s do it the other way round. Let me build a picture first, for both of us.’ She reaches for her fashionable handbag and pulls out a black notebook.

‘You’re taking notes.’ I can’t help bristling. ‘Really? You’re not my doctor, Tessa, you’re my friend. I saw loads of psychiatrists after the accident. What is the point of this? Who are you taking notes for, the police?’

She opens the notebook. Pen in hand. ‘No,’ she says calmly, and pauses. I can hear the moorland rain rattling on the windows. ‘No, not yet, Kath. We all really want to avoid anything like that.’

Again, I am put on the defensive, and simultaneously alarmed. Avoid the police? Why should the police be anywhere near this? That has all been dealt with. Adam handled all that. I was still in hospital. So why has he asked Tessa here to talk about the police?

I don’t know. But I have to believe my husband is doing this for a good reason, acting in my best interests. He must be. Adam has always done what’s best for me, and Lyla.

‘You met Adam when you were very young, isn’t that right?’

I shrug, bemused. Tessa surely knows this backstory almost as well as her own.

‘Tessa, you’re married to my bloody brother. Why do you even need to hear this stuff?’

‘I know some of it, Kath, yes, but—’ she sighs apologetically. ‘I really want to hear it from you. Please let me run with this?’

More mystery. Things are being hidden. In the back of the kitchen cupboard.

Taking a gulp of tea, I sigh. ‘I was seventeen, at a private girls’ school in Totnes.’

‘OK. Go on.’

‘Dan must have told you the story. We bunked off to the pub one day. I was underage, of course, so I was frightened to buy a drink, to break the rules, but then this very good-looking guy came up. It was Adam, he was eighteen. We went on a date the next day, started going steady the day after. He already had a job at the Park, as a trainee, and I went off to uni.’

‘Exeter. Yes.’

Her brisk smile is meant to be reassuring, I am not reassured.

‘I did archaeology, as you know.’

‘You enjoyed it?’

‘Sure. Yes. I really liked it.’

‘And you stuck with Adam?’

‘Yep.’ I smile, faintly, at the memory. ‘Everyone at university was sceptical, everyone scoffed and said Oh it won’t last, you’ll break up by Christmas, but I knew they were wrong, and they were wrong, and it did last, we stayed loyal, we had fun. Adam would come over to my halls of residence.’ I look her in the eyes. ‘Some days we never got up, just stayed in bed. After a few terms we got engaged. And when I graduated we got married. A year after you and Dan.’

Tessa takes more notes. Meanwhile, the January weather is at the windows, listening in, rattling panes. I wonder if the weather can hear my deeper thoughts, the occasional recurring doubts about my marriage, that trouble me from time to time: did I ever really deserve a handsome guy like Adam Redway? I know I brought the education to the marriage, and the faded poshness of the Kinnersleys: that was my side of the marital contract, but I’ve always thought I definitely got the best of the deal. Adam Redway: loyal, rugged, sexy – look at him, 100 per cent man. What did he see in her? I’ve watched women openly ogling my husband all the way through our marriage.

Has he stayed loyal? Does something like infidelity lie underneath this oddness? No. No. I do not believe that. Adam is loyal, and honest, and he loves me.

‘It’s around this time,’ Tessa says, scribbling away, ‘when you went off to uni, that your mother died?’

This is a change of tack. Now I feel vaguely affronted, again. ‘Look. I’m sorry, Tessa, and I don’t want to be rude, you’re always so kind to us, but … Can you please tell me why you’re here?’ I look at the clock on the cooker. ‘I’ve got work to do, too.’

‘Yes, I know, I’m sorry, Kath. I totally understand your confusion and irritation. But …’ She sets down her pen, and meets my gaze. ‘I need to colour in the blanks, and then I’ll tell you. It’s best we do it this way round. So that, you know—’

‘What? What do you have to tell me?’ I’m trying not to freak out. What can be so bad that Adam calls in my sister-in-law who happens to be a psychologist? Why does it need this long preamble, as if I am being prepared for the worst?

Tessa ignores the flush in my cheeks, and puts a pen to her notebook, ready to write. ‘Please, Kath, it’s best this way. Honestly.’

I look at her: the nice shoes from London, the cashmere cardigan. And I yield, wearily. ‘It was my second year at uni. Mum died in an ashram, when she was in India, which was typical of her.’

‘How do you mean, “typical”?’

‘Because Mum was always, like, alternative. Give her a crazy religion, Mum went for it. Reiki, Buddhism, wicca, astrology, shamanism, putting crystals up your bottom. She didn’t believe in things, she believed in everything. I think at one point she was simultaneously vegan, vegetarian, pescatarian, breatharian, and oddly fond of ribeye steak. And red wine. She always loved wine.’

Tessa smiles. ‘You miss her?’

I smile wistfully, in return. Oh yes. I miss Mum, even now. As I gaze across the kitchen I can see, on the shelf, one of the many souvenirs of her solo travels, when she would hare off to far corners of the world, dumping us kids with bemused but tolerant relatives; this particular souvenir is a garish, ancient doll from Greenland, an Inuit spirit-doll, I think, made of feathers and bird bones, with a leering face. Walrus teeth carved very crudely into human teeth. Yellow and awkward.

Adam hates this doll, I like it, because it’s Mum’s. She always loved eccentric things, quirky, broken, eerie things, stuff no one else liked. And I miss that artiness, that curiosity, and I miss her generous, scatterbrained foolishness, and I miss her wild and waspish wit. I also think I disappointed her. I was so normal, so conservative, wanting to fit in; yet in myself I loved her, revered her, despite her egotism, her partying.

I wished I could have showed it to her, more.

Looking back at Tessa I realize I have been lost in silence. For too long.

‘Yes,’ I say, sighing deeply, ‘I miss Mum. I miss her daily, even now. She was great fun, most of the time.’ I pause, and look at the smirking Inuit spirit-doll with its yellow teeth, like an old smoker. ‘Mum was Mum. Always herself. She grew up rich, I mean – you know we were an old family, the Kinnersleys. She used to talk about a big house in Dorset, long ago sold, but by the time it got to her, or at least me and Daniel, most of the money had gone and she was determined to spend the rest on experiences. She wanted to try everything, go everywhere, Greenland to Zambia, and she did. She used to say no one ever died wishing they’d bought a bigger TV: they died regretting things they didn’t do. Which is true, I think. I often wish I could live by those words, but I haven’t got the guts. Or the money.’

I take a breath. This is possibly the most I’ve spoken in one go since the accident. Which in itself is striking.

Tessa nods. Pen poised. ‘You never knew your father?’

‘Nope. Dan did a bit, but not me. No. He was American, based in London, and he wasn’t in her life that long, and never lived with us, never even lived in Devon, and he died when I was barely two, Daniel five. You should ask Dan about the funeral; by all accounts it was mad. Sitars and pentangles – and a Cornish harp. And Dad was pretty soon replaced.’ I chuckle, a little sadly, a little bitterly. ‘Mum was, you know, never into domesticity, never wanted to be bossed around, with a man around the house. But she certainly loved male attention, and men loved her back.’

Tessa looks at me. I can guess what she is thinking.

‘Of course Mum was a beauty, so I am told, but she bequeathed her looks to Dan. I got her intellectual curiosity, I think.’

‘I see. I see.’

Tessa squints at her notebook, and then looks at me, and I wonder if I can see embarrassment in her eyes. I sense an awkward question coming.

‘Let’s talk about your mother some more. The bequests. Does it hurt you that she left the Salcombe house entirely to Daniel?’

I flinch. Because, yes, this does hurt. It hurt a lot, and it sometimes still hurts, now. I look at Tessa’s expectant face. ‘Yes, that was pretty difficult. Emotionally.’ I am surprised at my own honesty; surprised by my vehemence. ‘The house was the last major asset Mum owned and she gave it all to my brother, supposedly because he’ – I do sarcastic air quotes with my fingers – ‘“always loved Salcombe so much more than me”, and Mum allegedly balanced it by giving me shares and antiques.’ I stare at the Dartmoor calendar on the kitchen wall, the picture of Kitty Jay’s grave, pretty and sad in the snow. ‘The shares and antiques turned out to be virtually worthless. Stuff my mum bought when she was stoned. God, she loved weed.’ I roll my eyes. ‘She used to buy it in Totnes from druids. I hate drugs. Hate them.’

Tessa writes brisk, efficient notes. Like a proper detective. I wonder if it is displacement activity, to hide her own discomfort. She glances at me.

‘So you still feel a certain resentment? Towards Dan, and your mother? About our Salcombe house?’

‘Yes. No. Oh, I don’t know. Yes, a little. But not really – I know there’s always that bit of friction between me and Dan, because of the house and all that, but I also love my brother. He’s an extrovert – not like me. He’s funny. And most of all we both endured Mum, together: that’s a profound bond, and of course it’s not his fault Mum was so scatty.’ Our eyes meet; I go on. ‘And of course I like you, Tessa, and I totally love your two little boys, and so, yes, sure, Dan has the big house, and yes, you guys get the money and the life, and we have to rent this place – but he’s loaned us cash when we’ve been hard up, you’ve bought holidays for me and Lyla, and that’s helped, Dan’s been a big, big help.’

‘OK. I see.’ Tessa is nearly expressionless. ‘And that brings us round to Lyla.’ She takes another sip of tea, which must be nearly cold. Mine is. ‘Let’s talk about that. And after that we’re nearly there, Kath.’

Nearly there? Nearly where? The tension builds like snow on snow – that snow which piles up and up, until the roof collapses.

‘You only had one child. Or have, I should say.’

‘Yes. We wanted more, but remember, Adam got Hodgkins, a few years back, and he needed chemo. And so he can’t have kids any more. So, as you know, Lyla is it. But it’s fine, he’s better. And I adore her, I love her, and Adam’s illness made us stronger.’ I push my mug away, defiantly. ‘It set us back financially, it was horrible – but we saw it through. It united us even more, and here we are. A family. A unit. This is who we are, and I like it.’

‘OK. This is my last question, Kath.’

‘Good.’

‘How are you coping with Lyla’s, ah, quirks?’

‘Her Asperger’s?’

‘She’s still not been officially diagnosed,’ Tessa says quickly, ‘As far as I am aware?’

‘No, but I reckon that’s what it is. Anyway, it means our lives are different; she still hates bustle and towns and loud noises, and new people, they make her panic, and she loves animals. So we live here, in the wilds, in the quiet, where we can have dogs, and there are horses. It’s fine, it’s all fine. Or it was until the bloody accident.’

Tessa nods and puts down her pen. My session, it seems, is over.

‘All right, taking all this into consideration, would you say that, on the whole, you were happy – or at least content – at the time of the accident at Burrator?’

‘Yes,’ I say, with some force: because it is true, and the truth is easy to say. ‘Tessa, that’s what makes it so awful! What gives me flashbacks, the horrors: I nearly lost it all. I have a husband I love, a daughter I love, a home I love, and I nearly lost it all, because of some stupid ice on a stupid Dartmoor road. I am very lucky. I’ve been given a second chance. I was actually technically dead for a few seconds!’ I shake my head, marvelling at my own luck. ‘Yes, life could be better: we need more money, Lyla needs help, it’s far from perfect, but what is money compared to life? No one ever died wishing they’d bought a bigger TV.’

Tessa smiles politely, yet I think I detect a faint, sad blush on her face. For a moment we both listen to the wind, knocking things over in the farmyard outside, like a drunk returning home from the pub. I wonder what Lyla is doing now. At school. Sitting alone in assembly, perhaps. Not talking to anyone. Ignored and friendless. Her mind wandering on to the moor, thinking of her newest bird feathers, and that piece of antler-felt her father found.

‘Kath, you clearly know you have retrograde amnesia? Because of the brain trauma?’

‘Yes. Of course! I know I’ve forgotten some stuff from before the crash, a week or so, but there are fragments, and the psychiatrists at the hospital say it will all come back. But, Jesus, I wish I could forget the actual crash! I still see the ice, the skid, the water – ugh—’

I close my eyes to dull the mental pain. When I open them, Tessa is frowning.

‘Well, the thing is, Kath: what the doctors at Derriford Hospital might not have properly explained about this amnesia is that you can forget that you’ve forgotten. That is to say, there are holes in your memory that you don’t even realize are there, and the mind tries to fill them.’

The wind has stopped abruptly. The whole house is quiet. I realize that the dogs must have gone with Adam and Lyla. All I can hear is Dartmoor rain on the window. A tinkly-tankly sound. I feel a sense of congealing fear. Some kind of horror is approaching. Like a moorland witch, creeping along the hedgerow. And we don’t have any hag stones. We have nothing to keep the witches away.

I can’t stand this any longer.

‘OK, this really is enough, Tessa. Tell me why you are here, in my kitchen?’ I am close to shouting. ‘I’ve told you everything. You know most of it already. So now it’s my turn to ask. Why are you here?’

‘Because,’ she says, looking deep, deep into my eyes, ‘you didn’t have an accident, Kath.’

‘What?’

‘Your mind has invented this. Invented the ice, invented it all.’

‘What?’ The panic rises in my throat, an acrid, metallic taste. ‘What? What do you mean? I had the bruises, I’ve seen the doctors. The bloody car is at the bottom of Burrator Reservoir. I had to buy a new one!’

‘Yes, it is. The car is down there. But that’s because you drove it in there, deliberately.’

I sense my life pivot around this moment. A ritual dance. ‘You mean – you mean – you can’t possibly—’

Tessa Kinnersley shakes her head, and I see the most enormous pity in her eyes. ‘Kath, there was no accident. You tried to leave your husband and daughter behind, to destroy yourself, to destroy everything. You tried to commit suicide. We just don’t know why.’

Later Thursday morning

Absolute stillness. That’s what it feels like. Absolute stillness, as if the beating heart of the world has slowed to a stop. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing. Then a lash of rain hits the windowpanes, breaking the quiet, and my words rush out.

‘How can you think that?’

Tessa remains calm, doing her job. She’s not here as a friend, but as a professional psychologist.

‘You were observed.’

‘Sorry?’

‘There was a witness at Burrator. By the reservoir. Walking his dog. It was night but there was a full moon, and he saw you drive your car, quite deliberately, into the water.’

‘But—’ The panic rises, like that black cold water, the water I can so vividly remember, and yet I can’t? ‘But. No. No way. Can’t be. There was ice. I skidded.’

‘Check the records, Kath, go back and look.’ Her arms folded, Tessa continues, her voice deliberately low and kind: overtly calming. ‘Go online and look at the weather for that night, December thirtieth. It was one of those dry and mild winter evenings we get. Twelve degrees centigrade. A southwest wind. There was no ice. Also …’ I flinch, inwardly.

‘Also, Kath, there is a wall around Burrator, you must remember that. A big, thick brick wall, a solid Victorian construction, far too strong for a car to smash through. You know Burrator well, you must recall this?’

She’s right. I do. There is a wall. Yet my mind has deceived me, recreated a different place: a place where I might drive in accidentally.

‘So how did I … I don’t get it—’ I swallow. I mustn’t cry.

Tessa guesses my question. ‘They were doing some construction at Burrator, rebuilding part of the wall, leaving a gap, barely wide enough for a car to slip through. The chances of skidding on ice, or whatever, and hitting the right spot would be pretty tiny, infinitesimal. But anyway you didn’t skid, and there was no ice, and you simply aimed the car, very carefully.’

‘There must have been someone else in the car.’

‘I’m sorry, it was you, just one person was seen, driving, and it was you. Only you drove into the reservoir; only you came out.’

‘I don’t believe it!’

The tears gather now. I stare, blurrily, up at that calendar. Kitty Jay’s grave, covered in snow, the flowers so forlorn against the whiteness. This is the famous beauty spot near Chagford, where my mother’s ashes are scattered: and I shrink inside. I huddle from the thought, the irony: what would Mum think of me? Of this terrible thing. Suicide? Like Kitty Jay herself? My mum loved life, she devoured it, despised the idea of suicide, and she taught that to me.

The words come again, all too quickly. ‘But why would I kill myself, Tessa? Why on earth would I do that? It’s hateful, suicide: it’s so selfish, the most selfish thing, and I was quite happy, I was. Yes, we had problems, with money, and Lyla, but I love her, I love – I love my husband – I love my daughter!’

And now the waters engulf me, and the truth pours in through the car window. Adam obviously knows all this, hence his cold anger, his strange distance, these past weeks. And I don’t blame him. What must he think of me? I tried to kill myself, for no apparent reason, I was prepared to leave him without a wife; and, worst of all, far worse, the deepest, darkest water of all, I was prepared to leave Lyla without a mother.

‘No,’ I say, flatly, defiantly. ‘NO. I don’t believe it. I would never do that. Never leave Lyla without a mother, never ever, ever. I am not that kind of woman, not that sort of mother! I love Lyla to bits. I would die for my daughter. Not die and leave her here. Oh God.’

I have to take a huge breath or I will shatter. I am a monster, a gargoyle. I am a leering thing made of dead birds and smeared blood. A horrible Inuit spirit-doll with feathers and yellow teeth. Here I sit in this warm bright kitchen with its ancient walls and the Come to Dartmouth tea towels: and yet I am something grotesque, a woman who would leave her lovely, fragile daughter without a mother … No.

‘I didn’t do it, Tessa. I didn’t! There has to be some other explanation.’

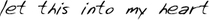

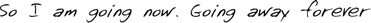

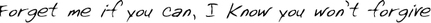

Tessa looks at me assessingly, as if judging how much I can take; reaching into her bag she lifts out a folded piece of paper, places it on the table. As she unfolds it, carefully, she reveals an image. The image looks scanned, photocopied. There seems to be handwriting on it, and it is small, introverted handwriting: scratchy and spidery.

I recognize this distinctive handwriting, from all the way across the kitchen table.

It is mine.

Tessa advises me, gently, ‘Adam has the original. This is a copy.’

I know what I am about to see: it is obvious. It doesn’t have to be said. But I also need to see it, to secure the lid on this. To hammer in the iron nails, so that no hope can escape.

Tessa pushes the paper across the table. With trembling hands I turn it around, and read my own handwriting:

The words are mine. I don’t remember writing them, don’t remember them at all, but this is my handwriting: I wrote this.

I tried to kill myself.

I shunt the paper aside, lean forward on my folded arms, gently rest my head on them. I can smell the clean, honest wood of our kitchen table, where I have spent so much time, with my husband, with my daughter, cooking suppers, drinking wine, laughing loudly, being a family. Here at this table. And now, at this same table, I quietly break into a sob, and keep sobbing.

Tessa says nothing, I stare down at the darkness between my arms, and sob and sob, in my white-painted kitchen. But I am not crying for me, I am crying for Adam, for my dead mother, for my brother, for this house, for this place around me, for the wildflowers on the high moors in the summer, for the meadowsweet at Whitehorse Hill, for the foxgloves down at Broada Marsh, for the sundews and shepherd’s dials and pennyroyals and roses – all the flowers my daughter loves, all the ones that she can name and I cannot, all the one she shows me, all the flowers and rocks and feathers she collects, because I am crying, crying, crying for my daughter, the little girl I was prepared to hurt, to damage, to dismiss, to throw away; the girl I picture, standing alone in the farmyard, listening for the tiny animals, puzzled in her anorak, wondering why her mother tried to run away forever.

To kill herself.

And my God. It is too much. And the rain tinkle-tankles on the window, as my tears run to their end.

How long I sit there, with my head slumped, I don’t know. An hour or more. But even the fiercest tears find a cease, as all things must die, and I lift my head. Tessa is sitting there patiently with a look of deep pity on her face.