The Spy Who Changed History

Ministers shook at the thought of what might happen if the fate of the reforming Tsar Alexander II, who had promised a modicum of universal education, was repeated. Alexander’s short-lived experiment with liberalisation had resulted in his assassination by anarchists. Lenin’s beloved older brother was hanged for his part in the plot. After that unhappy episode, the autocracy did everything it could to stifle education for the untrusted masses, from whom they demanded devotion. It was no surprise that adult literacy rates in Tsarist Russia were less than 30 per cent, while literacy among males was roughly double that of females. My own great-grandfather, a leading Communist in the Crimea, was unable to sign his name until he learned to read after the Revolution. (Today’s Russia has 99.7 per cent literacy.) As Professor Shumovsky, as he became, later told UNESCO, in 1917 only 9,656,000 students were in school out of a total population of around 175 million.22

The unenlightened policy held back the economic development of the country, as there was only a shallow pool of educated workers. Hundreds of thousands of Russia’s most literate individuals emigrated, primarily to the United States, taking their talent with them in a dramatic brain drain. With less than half the Tsar’s army able to read and write, the country was vulnerable to military attack. After the October Revolution, the idealist journalist John Reed (the only American to be interred after his death in the Kremlin Wall) wrote:

All Russia was learning to read, and reading – politics, economics, history because the people wanted to know … In every city, in most towns, along with the Front, each political faction had its newspaper – sometimes several. Hundreds of thousands of pamphlets were distributed by thousands of organizations and poured into the armies, the villages, the factories, the streets. The thirst for education, so long thwarted, burst with the Revolution into a frenzy of expression. From Smolny Institute alone, the first six months, went out every day tons, car-loads, train-loads of literature, saturating the land. Russia absorbed reading matter like hot sand drinks water, insatiable. And it was not fables, falsified history, diluted religion, and the cheap fiction that corrupts – but social and economic theories, philosophy, the works of Tolstoy, Gogol and Gorky.23

In the immediate aftermath of the October Revolution, education policy was overhauled with a tenfold increase in the expenditure on mass education. Lenin argued: ‘As long as there is such a thing in the country as illiteracy it is hard to talk about political education.’ Despite the utterly grim conditions, he launched national literacy campaigns. Victor Serge, a first-hand witness of the Communist Revolution, saw the tremendous odds facing educators and the miserable conditions that existed in the wake of the Russian Civil War. A typical school would have classes of hungry children in rags huddled in winter around a small stove planted in the middle of the classroom. The pupils shared one pencil between four of them, and their schoolmistress was hungry. In spite of this grotesque misery, such a thirst for knowledge sprang up all over the country that new schools, adult courses, universities and Workers’ Faculties were formed everywhere.24 In its first year of existence, the Communist literacy campaign reached an incredible five million people, of whom about half learned to read and write. In the Red Army, where literacy and education were deemed crucial, illiteracy was eradicated within seven years.

The Five-Year Plans and the Stalinist project to transform the Soviet economy were born of idealism as well as insecurity. The prospect of a great leap forward into a fully socialist economy kindled among a new generation of Party militants much the same messianic fervour as had inspired Lenin’s followers in the heady aftermath of the October Revolution and victory in the Civil War.

The young Communist idealists of the early 1930s, among them Soviet intelligence officers and other Russian students at MIT, believed in Stalin as well as in the coming ‘Triumph of Socialism’. Hailing from a generation who believed that the end justified the means, they would certainly not have recognised the prevailing view of Stalin among contemporary historians. The first group of elite Soviet students under the Politburo order was to be sent abroad in 1931. Individual Soviet specialists were already at many foreign universities, including a few in the US. The renowned Soviet atomic scientist Pyotr Kapitsa was number two in Ernest Rutherford’s team at the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University,fn6 while Dr Yakov Fishman learned about the chemistry of poison gases at the Italian university at Naples.

As Shumovsky and his party prepared to depart for the United States, US legal firm Simpson Thacher began the process of arranging the visas.25 (According to the 1948 FBI investigation,fn7 Shumovsky was a late addition to the roster. It is unclear if that was a decision taken in Moscow or one determined by the availability of places on courses.) Like Shumovsky, the students in his party were not fresh-faced teenagers just out of high school, but married ex-military men who had not been able to begin formal education until the end of the Russian Civil War in 1922 and had since been fast-tracked towards greatness. Many were from humble backgrounds and acutely aware that, but for the Communist Revolution, they would never have had any prospect of an education. Central to their motivation was the desire to enable Soviet industry and military technology to catch up with the West. The offices of the Rockefeller and Carnegie Foundations facilitated finding places at appropriate universities to help foster better international relations.26 Back in Moscow, the finance was organised. As with every decision in the Soviet system, the budget was decided centrally at a Politburo meeting in 1930. Several thousand gold roubles was allocated for the trip, amounting to a total fund of $1 million. Each student was assigned from a key industry and that industry’s management had the responsibility of paying.

The one tricky condition imposed by the American universities was that the students must demonstrate a high competence in English. Typically, the exam followed a two-year course, but this talented group was given just six months to reach the required standard.27 There was a desperate need for teachers to give the Soviet students English lessons in Moscow before they went off to study at MIT and other US universities. Among those selected for the task was Military Intelligence officer, American Ray Bennett. Another was Gertrude Klivans, a young Radcliffe College-educated teacher from a family of Russian-Jewish jewellers in Ohio.

• • •

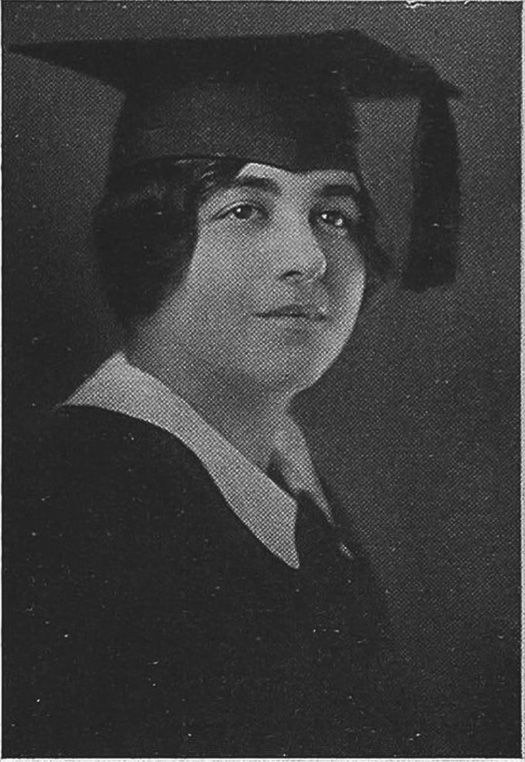

Klivans had become bored with life as a high school teacher in the Midwest and started travelling adventurously around the world. She was first talent-spotted by General Vitaly Markovich Primakov while both were journeying from Japan to Vladivostok aboard a cargo vessel, described by Klivans as ‘an ancient hulk’, which forced its small group of passengers to cling together ‘as we pitched and tossed’.28 Klivans’s letters to her family reveal that during the voyage she became quite friendly with Primakov.29 They clearly began an affair on board. Primakov, Klivans gushed to her family, was ‘the youngest full general in the Red Army’, a man whose travels (in fact they were spying missions) had taken him as far afield as Afghanistan, China and Japan: he ‘fought throughout the Revolution and on every battlefront during the Civil War – wears three medals, is always armed to the teeth – an expert swordsman and a cavalryman from a Cossack family that have been horsemen for generations, and withal, his head is shaven. But his eyes, the real gray blue, Russian eyes and fair skin make you forget that military custom.’

Gertrude Klivans, Radcliffe College, Harvard – yearbook. The picture is captioned: ‘Her eyes were stars of twilight fair/Like twilight, too, her dusky hair’

Klivans reported to her family that, during the long trans-Siberian train journey from Vladivostok to Moscow, ‘I spent most of every day in Primakov’s compartment, so I enjoyed all the privileges of first class, even accepting the offer of taking a bath.’ She fell deeply in love. Although the train arrived a day late, ‘I didn’t care – I didn’t want it ever to end.’ She had intended to return to New York, but Primakov promised to help her find a teaching job in Moscow. Remarkably, she admitted to her family that he had suggested she work for Soviet intelligence: ‘Imagine – I was offered a job in the [O.] G. P. U.fn8 as soon as I learned the [Russian] language.’

Primakov had enjoyed a glittering career in the Red Army and the intelligence service. He cut his teeth leading a squadron of troops in the attack on the Petrograd Winter Palace in 1917. The highlight of his espionage career came in 1929 when, disguised as a Turkish officer named Ragib-bey, he led a special operation of Soviet troops to try to reinstate Amanullah Khan as ruler of Afghanistan. He was arrested in 1936 and executed in the following year’s Great Purge.30

Although in letters to her family Klivans complained that living conditions in Moscow had left her with ‘a few bedbug bites’, she declared herself ‘very happy with my work’. She worked diligently to teach her charges all about America:

You can’t imagine how well I know these boys, all of whom are at least five years older [than me] … They will do anything for me and believe me I do plenty for them, besides keeping them in cigarettes and informing them of certain Americanisms. I mean as far as deportment is concerned, I try to make each of them letter perfect in the President’s English and if you think it isn’t hard work you are mistaken. But there are always three at least who are making love to me outside of school hours so that I can never keep a straight face for at least five minutes going in class. If you would see them, all in their fur hats, high felt boots, and a week’s beard for nobody shaves more than once in five days you would laugh. But they are fun, and I certainly will always have 15 fast friends in Russia. Probably someday one of them will be another Stalin – they are all party men, active and so understanding of my distorted view of life as they can understand the limitations of my bourgeois environment, the only thing they can’t understand is why I haven’t already embraced Communism without any reservations.31

To celebrate the end of the examinations after her language course, Klivans threw a party for the students on 15 April 1931, for which she prepared the closest approximation she could manage to American sandwiches and salads. The only woman at the party, she wore a ‘Chinese suit’ acquired on her travels. It was an emotional occasion with many hours of dancing and singing. Klivans travelled to the United States ahead of her Russian students, describing them in her letter home:

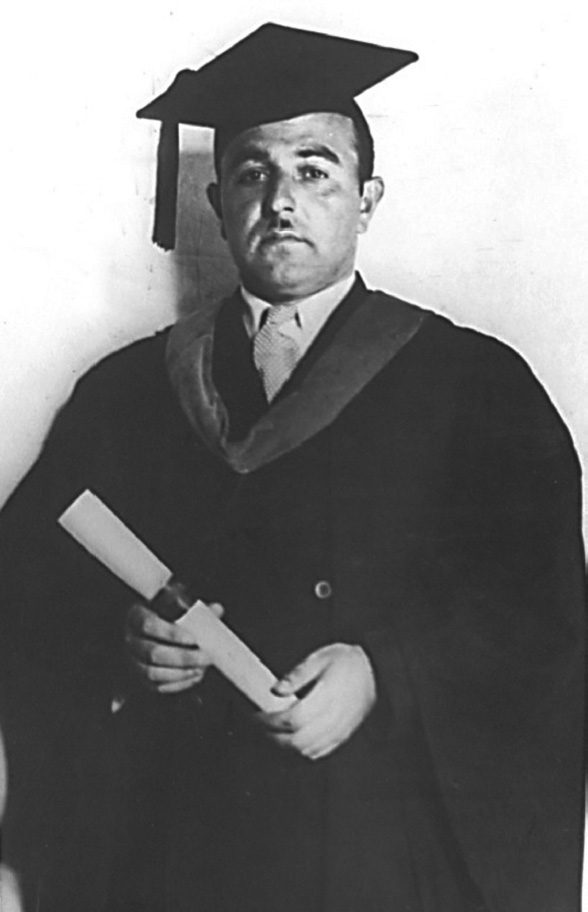

Let me tell you who the boys are. They are all 27 or 28. One [Alexander Gramp] is half Georgian and half Armenian – speaks both of these languages and knows every place on the map of Russia with his eyes shut – has a disposition that even Russian conditions cannot spoil. Another is a White Russian [MIT-bound Eugene Bukley] – as clever as any three people I’ve met and had a sense of humor that works equally well in any language – the third [Peter Ivanov, a future student at Harvard] is a serious electrical engineer who served as a sort of lever in our hilarious spirits. Of the first two, one is a railway engineer, in fact, that got us tickets everywhere – something almost unheard of in Russia today. The other one is also an electrical engineer.32

Alexander Gramp’s graduation, Purdue University,1933

Klivans’s closest relationship was with the railway engineer, Gramp, one of the five students with a place at Purdue University. He married her after his graduation, returning with her to Moscow following his appointment as Dean of the College of Railway Engineering.

Eager to ensure that her students made a good impression on their arrival at MIT and other US universities, Klivans pressed successfully for scarce foreign currency reserves. When they landed in New York, she wanted to buy them smart, well-cut suits.

3

‘WHAT THE COUNTRY NEEDS IS A REAL BIG LAUGH’

To the disappointment and astonishment of Communists, the American working people did not rise up en masse during the Great Depression to demand even the overhaul – much less the overthrow – of their system of democratic capitalism, despite the failure to relieve their sufferings for more than a decade. Arriving at the height of the economic misery, a confident Gertrude Klivans held court in her stateroom on SS Bremen at the New York docks. She was back at long last in the United States, a returning political pilgrim and a secret convert to Communism. While she was already an agent of INO, Klivans did not consider herself a traitor to the US, but rather a contributor to helping the peoples of the Soviet Union.

Her courtiers were a small crowd of journalists, fans of the small-town socialite-turned-adventurer. She was a Youngstown, Ohio celebrity. Local magazines had serialised parts of the letters she had written to her family from the mysterious, godless USSR describing most of her adventures. Exposure to the socialist experiment had transformed her in just a year from a frustrated English Literature teacher at the local high school into a confident woman, delighted to be sought out for her views on the world. She was secretly engaged, if not already married, to her fellow agent Alexander Gramp. She adroitly ducked answering questions from the wire services on international politics, but was more than happy to announce that the first Soviet Five-Year Plan was a resounding success. Joseph Stalin must have been pleased. The journalists asked her if it was possible to teach the Soviet leaders anything. She replied, ‘Indeed yes, in fact, they are the most teachable people to be found.’1

Amid America’s worst ever socio-economic crisis, Klivans delivered the message that a socialist future was the answer to her society’s ills. Before October 1929 the United States had believed that it would enjoy an uninterrupted period of increasing prosperity. This mirage was not an invention of the people but was what they had been told by their leaders. In his last State of the Union address in 1928, President Calvin Coolidge had said: ‘No Congress of the United States ever assembled, on surveying the state of the Union, has met with a more pleasing prospect than that which appears at the present time.’2 He had overseen an expanding economy based on easy access to consumer loans for housing, its citizens buying vast numbers of new automobiles on credit instalment plans. The vehicles, once a luxury, were now commonplace and seemingly affordable; there was even a fear that the car would create an amoral society as young couples were now out of sight of their parents. That great barometer of America’s health, the stock market indices, were not merely soaring on the back of the credit bubble; they went through the roof. The Dow Jones Industrial Average quadrupled between 1924 and 1929. America appeared to be on the brink of economic greatness.

Led by New York, the modern cities of the USA were a bustling hive of theatre, movies, arts, food and sober fun. Based on its global leadership in technological innovation, mass production and consumerism, America had overtaken the British Empire as the pre-eminent economic power in the world. When Herbert Hoover campaigned for the presidency in 1928, he assured the country it could expect ever greater economic prosperity. In a campaign speech, he said: ‘We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land. We shall soon, with the help of God, be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation.’3

Hoover would later quip that he was the first man in history to have a depression named after him. For all these dreams came crashing down in just a few days in 1929, and for the next decade, even the Big Apple became a sombre city of hopeless, desperate people. The stock market crash began on 24 October and ended on the 29th. In a matter of four days, America saw $30 billion of its wealth wiped out for ever. Within months New Yorkers were starving to death. Large crowds of bewildered investors, bank workers and concerned citizens wandered around Wall Street in a daze during the crash. In an attempt to exercise some control the police began making arrests. After the initial panic, worse was to follow.

The administration estimated that any recession resulting from the crash would be shallow, like the one the United States had experienced after the Great War. Despite the high drama, the conservative President Hoover believed that ‘anything can make or break a market … from the failure of a bank to the rumor that your second cousin’s grandmother has a cold’.4 He and his laissez-faire economist advisors thought it was just a small setback and the market would soon bounce back. It didn’t. Publicly, Hoover continually downplayed the nation’s agony, retreating into his dogmatic shell and refusing to act. At this most difficult time, he offered his wounded people no leadership. In the face of the suffering and bewilderment, the White House appeared distant and unmoving.

Throughout the crisis, Hoover would display terrible judgement. One of his most passionate causes was to deny combat veterans an increase in their benefits. When it came to providing depression relief, he insisted that private charity, not state aid, funnelled through the Red Cross was sufficient. He went further, expressing the belief that charity was the sole answer to the enormous and growing needs of America’s army of unemployed and starving. He kept up this line even when nature added to the misery, a severe drought creating a dust bowl in the Great Plains region. In a White House press interview Hoover displayed shocking callousness towards his fellow citizens. ‘Nobody is starving,’ the President blithely asserted. ‘The hoboes are better fed than they ever were before.’5 New York City alone reported ninety-five cases of death by starvation that year.

Describing the start of the Great Depression as merely public hysteria, Hoover declared that ‘what the country needs is a real big laugh. If someone could get off a good joke every ten days, I think our troubles would be over in two months.’6 Far from being gripped by laughter, waves of bank runs began in New York City and spread panic around the country. In fear customers flooded into their banks to take out their savings. The banks didn’t have any cash; no one did. By 1931 it became evident that many banks were going out of business. In December, the Bank of the United States in New York collapsed, having at one stage held more than $210 million in customer deposits. It was a tipping point, and within the next month 300 other banks failed. By April 1932, more than 750,000 people in New York alone were on some form of welfare and a further 160,000 were on the waiting list. In desperation, crowds of unemployed men took to wandering the streets wearing signs showcasing their skills in an attempt to find work.

• • •

Klivans gave a series of detailed, teasing interviews to the newspapers about some of her experiences during her ten months teaching English in Russia. Amid the chaos, she sat on an upholstered chair in her parents’ elegant drawing room wearing an evening gown for the first time since she had left Youngstown society life to venture into the heart of the Soviet Union. One journalist asked the burning question:

it’s raining outside; you are alone in the house, lonely. At the door stand two young men, one Russian, a senior of Moscow University; the other is a Harvard senior. Which would you prefer as company for the evening?’ Klivans replied, ‘I’d prefer the Russian because he is more mature, more intelligent, not so flippant and doesn’t neck. Necking is not a national pastime in Russia. Sex is delegated to secondary importance. Work comes first, then sex. What is immoral in America is moral in Russia.’7

A mildly irritated Klivans knew the exact lines to prick the journalist’s interest: ‘Russians can’t understand America’s exploitation of sex.’ While in Moscow she had shared with her class pictures from American periodicals of bathing beauties in toothpaste and mouthwash adverts. The reaction was merely raised Russian eyebrows and quizzical smiles. She announced that Soviet society had developed very progressive answers to America’s fixations with sex, drinking, divorce and religion. None of the curses of American life existed in the Soviet Union, she believed, and unlike America, there was practically no graft in government. She had found there to be few courts to speak of, no instalment credit plans and few automobiles. Divorce rates had soared in the US during the economic crisis as the strain of unemployment took a vicious toll on relationships, and the busy divorce lawyers were reviled; in the Soviet Union, she believed, divorce and other lawyers were unknown. Klivans spoke of the very different ideas towards love and marriage found in the Soviet Union, where it was now the case that ‘whether registered or not the marriage is legal, and the parties can separate permanently without any more ado about it. No five day waiting is required when a Russian wants to get married. He just goes ahead and gets married. If he likes, he can register the marriage, and this means that if he leaves her their property will be equally distributed.’8

Some American scaremongers peddled the myth that Communism was synonymous with an amoral society. In Klivans’s view, it was American society, whose members had sex in cars, which was promiscuous, and not the atheist Russians. Cars in Russia were few in number and used exclusively for work. It was freedom-loving Americans, she continued, who had to be deprived of alcohol by their own government’s prohibition laws. America’s deprived drinkers would be jealous of the Russians, who took their daily drinking quite seriously. And yet, despite the ready availability of alcohol, there were in her experience few real drunkards in evidence on the streets of Moscow or Leningrad. Wine and beer were the favoured tipples. Seemingly Russians could be trusted to behave themselves responsibly with alcohol, whereas Americans could not. Moreover, she believed that religion was not prohibited in Russia, although as a result of pressure brought to bear on those who attended worship most Russians did not attend church. Overall she challenged the alarmist conservative view that a lack of religious training in Russia had lowered the moral standard of the country.

Painting a picture of a society with difficult economic problems but one that had embarked on an exciting journey to a much better future, she confirmed to readers that despite the advantages of some aspects of the Communist system, there were extreme shortages of the basics in the Soviet Union. ‘One cannot buy the most trivial thing in Russia such as knives, scissors, screwdrivers, thumb tacks and the thousand and one other things that are so common in our five and ten cent store. An American five and ten cent store transplanted to Russia would probably give the Russians the impression that the millennium had arrived.’9 But Klivans was a convert, as she had found living in Russia had given her a tremendous feeling of stimulation at being part of an energetic society where everyone worked for a definite purpose. She would get her wish to go back to what she described as ‘the most exciting place on the globe’. She was not alone. Many fellow left-leaning US thinkers had already made similar pilgrimages to Moscow.