John Bull, Junior: or, French as She is Traduced

"No, sir; I will take you there for a shilling," he replies.

"Oh! thank you; I think I will walk then."

Cabby retires muttering a few sentences unintelligible to me. Only one word constantly occurring in his harangue can I remember.

I open my pocket-dictionary.

Good heavens! What have I said to the man? What has he taken me for? Have I used words conveying to his mind any intention of mine to take his precious life? Do I look ferocious? Why did he repeatedly call me sanguinaire? Must have this mystery cleared up.

10th July, 1872An English friend sets my mind at rest about the little event of yesterday. He informs me that the adjective in question carries no meaning. It is simply a word that the lower classes have to place before each substantive they use in order to be able to understand each other.

Have taken apartments in the neighborhood of Baker Street. My landlady, qui frise ses cheveux et la cinquantaine, enjoys the name of Tribble. She is a plump, tidy, and active-looking little woman.

On the door there is a plate, with the inscription,

"J. Tribble, General Agent."Mr. Tribble, it seems, is not very much engaged in business.

At home he makes himself useful.

It was this gentleman, more or less typical in London, whom I had in my mind's eye as I once wrote:

"The English social failure of the male sex not unfrequently entitles himself General Agent: this is the last straw he clutches at; if it should break, he sinks, and is heard of no more, unless his wife come to the rescue, by setting up a lodging-house or a boarding-school for young ladies. There, once more in smooth water, he wields the blacking-brush, makes acquaintance with the knife-board, or gets in the provisions. In allowing himself to be kept by his wife, he feels he loses some dignity; but if she should adopt any airs of superiority over him, he can always bring her to a sense of duty by beating her."

Mr. Tribble helps take up my trunks. On my way to bed my landlady informs me that her room adjoins mine, and if I need any thing in the night I have only to ask for it.

This landlady will be a mother to me, I can see.

The bed reminds me of a night I passed in a cemetery, during the Commune, sleeping on a gravestone. I turn and toss, unable to get any rest.

Presently I had the misfortune to hit my elbow against the mattress.

A knock at the door.

"Who is there?" I cry.

"Can I get you any thing, sir? I hope you are not ill," says a voice which I recognize as that of my landlady.

"No, why?"

"I thought you knocked, sir."

"No. Oh! I knocked my elbow against the mattress."

"Ah! that's it. I beg your pardon."

I shall be well attended here, at all events.

The table here is not recherché; but twelve months' campaigning have made me tolerably easy to please.

What would not the poor Parisians have given, during the Siege in 1870, for some of Mrs. Tribble's obdurate poultry and steaks!

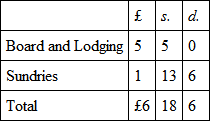

I ask Mrs. Tribble for my bill.

I received it immediately; it is a short and comprehensive one:

I can understand "lodging"; but "board" is a new word to me. I like to know what it is I have to pay for, and I open my dictionary.

"Board (subst.), planche."

Planche! Why does the woman charge me for a planche? Oh! I have it – that's the bed, of course.

My dictionary does not enlighten me on the subject of "Sundries."

I make a few observations to Mrs. Tribble on the week's bill. This lady explains to me that she has had great misfortunes, that Tribble hardly does any work, and does not contribute a penny toward the household expenses. When he has done a little stroke of business, he takes a holiday, and only reappears when his purse is empty.

I really cannot undertake to keep Tribble in dolce far niente, and I give Mrs. Tribble notice to leave.

9 A.M. – I read in this morning's paper the following advertisement:

"Residence, with or without board, for a gentleman, in a healthy suburb of London. Charming house, with creepers, large garden; cheerful home. Use of piano, etc."

"Without board" is what I want. Must go and see the place.

6 P.M. – I have seen the house with creepers, and engaged a bedroom and sitting-room. Will go there to-night. My bed is provided with a spring mattress. Won't I sleep to-night, that's all!

I remove my goods and chattels from the charming house. I found the creepers were inside.

It will take me a long time to understand English, I am afraid.

I examine my financial position. I came to England with fifty pounds; have been here thirty days, and have lived at the rate of a pound a day. My money will last me only twenty days longer. This seems to be a simple application of the rule of three.

The thought that most Lord-Mayors have come to London with only half-a-crown in their pockets comforts me. Still I grow reflective.

25th September, 1872I can see that the fee I receive for the weekly letter I send to my Parisian paper will not suffice to keep me. Good living is expensive in London. Why should I not reduce my expenses, and at the same time improve my English by teaching French in an English school as resident master? This would enable me to wait and see what turn events will take.

I have used my letters of recommendation as a means of obtaining introductions in society, and my pride will not let me make use of them again for business.

I will disappear for a time. When my English is more reliable, perhaps an examination will open the door of some good berth to me.

Received this morning an invitation to be present at a meeting of the Teachers' Association.

Came with a friend to the Society of Arts, where the meeting is held in a beautiful hall, and presided over by Canon Barry.

What a graceful and witty speaker!

He addresses to private school-masters a few words on their duty.

"Yours," he says, "is not only a profession, it is a vocation, I had almost said a ministry" (hear, hear), "and the last object of yours should be to make money."

This last sentence is received with rapturous applause. The chairman has evidently expressed the feeling of the audience.

The Canon seems to enjoy himself immensely.

Beautiful sentiments! I say to myself. Who will henceforth dare say before me, in France, that England is not a disinterested nation? Yes, I will be a school-master; it is a noble profession.

A discussion takes place on the merits of private schools. A good deal of abuse is indulged in at the expense of the public schools.

I inquire of my friend the reason why.

My friend is a sceptic. He says that the public schools are overflowing with boys, and that if they did not exist, many of these private school-masters would make their fortune.

I bid him hold his wicked tongue. He ought to be ashamed of himself.

The meeting is over. The orators, with their speeches in their hands, besiege the press reporters' table. I again apply to my friend for the explanation of this.

He tells me that these gentlemen are trying to persuade the reporters to insert their speeches in their notes, in the hope that they will be reproduced in to-morrow's papers, and thus advertise their names and schools.

My friend is incorrigible. I will ask him no more questions.

There will be some people disappointed this morning, if I am to believe what my friend said yesterday. I have just read the papers. Under the heading "Meeting of the Teachers' Association," I see a long report of yesterday's proceedings at the Society of Arts. Canon Barry's speech alone is reproduced.

For many months past, M. Thiers has carried the Government with his resignation already signed in his frockcoat pocket.

"Gentlemen," he has been wont to say in the Houses of Parliament, "such is my policy. If you do not approve it, you know that I do not cling to power; my resignation is here in my pocket, and I am quite ready to lay it on the table if you refuse me a vote of confidence."

I always thought that he would use this weapon once too often.

A letter, just received from Paris, brings me the news of his overthrow and the proclamation of Marshal MacMahon as President of the Republic.

The editor of the French paper, of which I have been the London correspondent for a few months, sends me a check, with the sad intelligence that one of the first acts of the new Government has been to suppress our paper.

Things are taking a gloomy aspect, and no mistake.

To return to France at once would be a retreat, a defeat. I will not leave England, at any rate, before I can speak English correctly and fluently. I could manage this when a child; it ought not to take me very long to be able to do the same now.

I pore over the Times educational advertisements every day.

Have left my name with two scholastic agents.

25th June, 1873I have put my project into execution, and engaged myself in a school in Somersetshire.

The post is not a brilliant one, but I am told that the country is pretty, my duties light, and that I shall have plenty of time for reading.

I buy a provision of English books, and mean to work hard.

In the mean time, I write to my friends in France that I am getting on swimmingly.

I have always been of the opinion that you should run the risk of exciting the envy rather than the pity of your friends, when you have made up your mind not to apply to them for a five-pound note.

Arrived here yesterday. Find I am the only master, and expected to make myself generally useful. My object is to practice my English, and I am prepared to overlook many annoyances.

Woke up this (Sunday) morning feeling pains all over. Compared to this, my bed at Mrs. Tribble's was one of roses. I look round. In the corner I see a small washstand. A chair, a looking-glass six inches square hung on the wall, and my trunk, make up the furniture.

I open the window. It is raining a thick, drizzling rain. Not a soul in the road. A most solemn, awful solitude. Horrible! I make haste to dress. From a little cottage, on the other side of the road, the plaintive sounds of a harmonium reach me. I sit on my bed and look at my watch. Half an hour to wait for my breakfast. The desolate room, this outlook from the window, the whole accompanied by the hymn on the harmonium, are enough to drive me mad. Upon my word, I believe I feel the corner of my eye wet. Cheer up, boy! No doubt this is awful, but better times will come. Good heavens! You are not banished from France. With what pleasure your friends will welcome you back in Paris! In nine hours, for a few shillings, you can be on the Boulevards.

Breakfast is ready. It consists of tea and bread and butter, the whole honored by the presence of Mr. and Mrs. R. I am told that I am to take the boys to church. I should have much preferred to go alone.

On the way to church we met three young ladies – the Squire's daughters, the boys tell me. They look at me with a kind of astonishment that seems to me mixed with scorn. This is probably my fancy. Every body I meet seems to be laughing at me.

20th August, 1873Am still at M., teaching a little French and learning a good deal of English.

Mrs. R. expresses her admiration for my fine linen, and my wardrobe is a wonder to her. From her remarks, I can see she has taken a peep inside my trunk.

Received this morning a letter from a friend in Paris. The dear fellow is very proud of his noble ancestors, and his notepaper and envelopes are ornamented with his crest and crown. The letter is handed to me by Mrs. R., who at the same time throws a significant glance at her husband. I am a mysterious person in her eyes, that is evident. She expresses her respect by discreetly placing a boiled egg on my plate at breakfast. This is an improvement, and I return thanks in petto to my noble friend in Paris.

Whatever may be Mr. R.'s shortcomings, he knows how to construct a well-filled time-table.

I rise at six.

From half-past six to eight I am in the class-room seeing that the boys prepare their lessons.

At eight I partake of a frugal breakfast.

From half-past eight till half-past nine I take the boys for a walk.

From half-past nine till one I teach more subjects than I feel competent to do, but I give satisfaction.

At one I dine.

At five minutes to two I take a bell, and go in the fields, ringing as hard as I can to call the boys in.

From two to four I teach more subjects than – (I said that before).

After tea I take the boys for a second walk.

My evenings are mine, and I devote them to study.

Mr. R. proposes that I should teach two or three new subjects. I am ready to comply with his wishes; but I sternly refuse to teach la valse à trois temps.

He advises me to cane the boys. This also I refuse to do.

I cannot stand this life any longer. I will return to France if things do not take a brighter turn.

I leave Mr. R. and his "Dotheboys Hall."

At the station I meet the clergyman. He had more than once spoken to me a few kind words. He asks me where I am going.

"To London, and to Paris next, I hope," I reply.

"Are you in a hurry to go back?"

"Not particularly; but – "

"Well, will you do my wife and myself the pleasure of spending a few days with us at the Vicarage? We shall be delighted if you will."

"With all my heart."

Have spent a charming week at the Vicarage – a lovely country-house, where for the first time I have seen what real English life is.

I have spoken to my English friend of my prospects, and he expresses his wonder that I do not make use of the letters of recommendation that I possess, as they would be sure to secure a good position for me.

"Are not important posts given by examination in this country?" I exclaimed.

But he informs me that such is not the case; that these posts are given, at elections, to the candidates who are bearers of the best testimonials.

The information is most valuable, and I will act upon my friend's advice.

My visit has been as pleasant as it has been useful.

A vacancy occurred lately in one of the great public schools. I sent in my application, accompanied by my testimonials.

Have just received an official intimation that I am elected head-master of the French school at St. Paul's.

One piece of good luck never comes alone.

I am again appointed London correspondent to one of the principal Paris papers.

Allons, me voilà sauvé!

III

I Make the Acquaintance of Public School Boys. – "When I Was a Little Boy." – An Awful Moment. – A Simple Theory. – I Score a Success.

I am not quite sure that the best qualification for a school-master is to have been a very good boy.

I never had great admiration for very good boys. I always suspected, when they were too good, that there was something wrong.

When I was at school, and my master would go in for the recitation of the litany of all the qualities and virtues he possessed when a boy – how good, how dutiful, how obedient, how industrious he was – I would stare at him, and think to myself: How glad that man must be he is no longer a boy!

"No, my dear little fellows, your master was just like you when he was mamma's little boy. He shirked his work whenever he could; he used to romp and tear his clothes if he had a chance, and was far from being too good for this world; and if he was not all that, well, I am only sorry for him, that's all."

I believe that the man who thoroughly knows all the resources of the mischievous little army he has to fight and rule is better qualified and prepared for the struggle.

We have in French an old proverb that says: "It's no use trying to teach an old monkey how to make faces."

The best testimonial in favor of a school-master is that the boys should be able to say of him: "It's no use trying this or that with him; he always knows what we are up to."

How is he to know what his pupils are "up to" if he has not himself been "up to" the same tricks and games?

The base of all strategy is the perfect knowledge of all the roads of the country in which you wage war.

To be well up in all the ways and tricks of boys is to be aware of all the moves of the enemy.

It is an awful moment when, for the first time, you take your seat in front of forty pairs of bright eyes that are fixed upon you, and seem to say:

"Well, what shall it be? Do you think you can keep us in order, or are we going to let you have a lively time of it?"

All depends on this terrible moment. Your life will be one of comfort, and even happiness, or one of utter wretchedness.

Strike the first blow and win, or you will soon learn that if you do not get the better of the lively crew they will surely get the better of you.

I was prepared for the baptism of fire.

I even had a little theory that had once obtained for me the good graces of a head-master.

This gentleman informed me that the poor fellow I was going to replace had shot himself in despair of being ever able to keep his boys in order, and he asked me what I thought of it.

"Well," I unhesitatingly answered, "I would have shot the boys."

"Right!" he exclaimed; "you are my man."

If, as I strongly suspected from certain early reminiscences, to have been a mischievous boy was a qualification for being a good school-master, I thought I ought to make a splendid one.

The result of my first interview with British boys was that we understood each other perfectly. We were to make a happy family. That was settled in a minute by a few glances at each other.

IV

The "Genus" Boy. – The Only One I Object To. – What Boys Work For.

Boys lose their charm when they get fifteen or sixteen years of age. The clever ones, no doubt, become more interesting to the teacher, but they no longer belong to the genus boy that you love for his very defects as much as for his good qualities.

I call "boys" that delightful, lovable race of young scamps from eleven to fourteen years old. At that age all have redeeming points, and all are lovable. I never objected to any, except perhaps to those who aimed at perfection, especially the ones who were successful in their efforts.

For my part, I like a boy with a redeeming fault or two.

By "boys" I mean little fellows who manage, after a game of football, to get their right arm out of order, that they may be excused writing their exercises for a week or so; who do not work because they have an examination to prepare, but because you offer them an inducement to do so, whether in the shape of rewards, or maybe something less pleasant you may keep in your cupboard.

V

School Boys I have Met. – Promising Britons. – Sly-Boots. – Too Good for this World. – "No, Thanks, We Makes It." – French Dictionaries. – A Naughty Boy. – Mothers' Pets. – Dirty but Beautiful. – John Bully. – High Collars and Brains. – Dictation and its Trials. – Not to be Taken In. – Unlucky Boys. – The Use of Two Ears. – A Boy with One Idea. – Master Whirligig. – The Influence of Athletics. – A Good Situation. – A Shrewd Boy of Business. – Master Algernon Cadwaladr Smyth, and Other Typical Schoolboys.

Master Johnny Bull is a good little boy who sometimes makes slips in his exercises, but mistakes – never.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

1

Things have changed in England since the dynamite scare.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги