History of the Plague in London

It must not be forgot here that the city and suburbs were prodigiously full of people at the time of this visitation, I mean at the time that it began. For though I have lived to see a further increase, and mighty throngs of people settling in London, more than ever; yet we had always a notion that numbers of people which – the wars being over, the armies disbanded, and the royal family and the monarchy being restored – had flocked to London to settle in business, or to depend upon and attend the court for rewards of services, preferments, and the like, was42 such that the town was computed to have in it above a hundred thousand people more than ever it held before. Nay, some took upon them to say it had twice as many, because all the ruined families of the royal party flocked hither, all the soldiers set up trades here, and abundance of families settled here. Again: the court brought with it a great flux of pride and new fashions; all people were gay and luxurious, and the joy of the restoration had brought a vast many families to London.43

But I must go back again to the beginning of this surprising time. While the fears of the people were young, they were increased strangely by several odd accidents, which put altogether, it was really a wonder the whole body of the people did not rise as one man, and abandon their dwellings, leaving the place as a space of ground designed by Heaven for an Aceldama,44 doomed to be destroyed from the face of the earth, and that all that would be found in it would perish with it. I shall name but a few of these things; but sure they were so many, and so many wizards and cunning people propagating them, that I have often wondered there was any (women especially) left behind.

In the first place, a blazing star or comet appeared for several months before the plague, as there did, the year after, another a little before the fire. The old women, and the phlegmatic hypochondriac45 part of the other sex (whom I could almost call old women too), remarked, especially afterward, though not till both those judgments were over, that those two comets passed directly over the city, and that so very near the houses that it was plain they imported something peculiar to the city alone; that the comet before the pestilence was of a faint, dull, languid color, and its motion very heavy, solemn, and slow, but that the comet before the fire was bright and sparkling, or, as others said, flaming, and its motion swift and furious; and that, accordingly, one foretold a heavy judgment, slow but severe, terrible, and frightful, as was the plague, but the other foretold a stroke, sudden, swift, and fiery, as was the conflagration. Nay, so particular some people were, that, as they looked upon that comet preceding the fire, they fancied that they not only saw it pass swiftly and fiercely, and could perceive the motion with their eye, but even they heard it; that it made a rushing, mighty noise, fierce and terrible, though at a distance, and but just perceivable.

I saw both these stars, and, I must confess, had had so much of the common notion of such things in my head, that I was apt to look upon them as the forerunners and warnings of God's judgments, and, especially when the plague had followed the first, I yet saw another of the like kind, I could not but say, God had not yet sufficiently scourged the city.

The apprehensions of the people were likewise strangely increased by the error of the times, in which I think the people, from what principle I cannot imagine, were more addicted to prophecies, and astrological conjurations, dreams, and old wives' tales, than ever they were before or since.46 Whether this unhappy temper was originally raised by the follies of some people who got money by it, that is to say, by printing predictions and prognostications, I know not. But certain it is, books frighted them terribly, such as "Lilly's Almanack,"47 "Gadbury's Astrological Predictions," "Poor Robin's Almanack,"48 and the like; also several pretended religious books, – one entitled "Come out of Her, my People, lest ye be Partaker of her Plagues;"49 another called "Fair Warning;" another, "Britain's Remembrancer;" and many such, – all, or most part of which, foretold directly or covertly the ruin of the city. Nay, some were so enthusiastically bold as to run about the streets with their oral predictions, pretending they were sent to preach to the city; and one in particular, who, like Jonah50 to Nineveh, cried in the streets, "Yet forty days, and London shall be destroyed." I will not be positive whether he said "yet forty days," or "yet a few days." Another ran about naked, except a pair of drawers about his waist, crying day and night, like a man that Josephus51 mentions, who cried, "Woe to Jerusalem!" a little before the destruction of that city: so this poor naked creature cried, "Oh, the great and the dreadful God!" and said no more, but repeated those words continually, with a voice and countenance full of horror, a swift pace, and nobody could ever find him to stop, or rest, or take any sustenance, at least that ever I could hear of. I met this poor creature several times in the streets, and would have spoke to him, but he would not enter into speech with me, or any one else, but kept on his dismal cries continually.

These things terrified the people to the last degree, and especially when two or three times, as I have mentioned already, they found one or two in the bills dead of the plague at St. Giles's.

Next to these public things were the dreams of old women; or, I should say, the interpretation of old women upon other people's dreams; and these put abundance of people even out of their wits. Some heard voices warning them to be gone, for that there would be such a plague in London so that the living would not be able to bury the dead; others saw apparitions in the air: and I must be allowed to say of both, I hope without breach of charity, that they heard voices that never spake, and saw sights that never appeared. But the imagination of the people was really turned wayward and possessed; and no wonder if they who were poring continually at the clouds saw shapes and figures, representations and appearances, which had nothing in them but air and vapor. Here they told us they saw a flaming sword held in a hand, coming out of a cloud, with a point hanging directly over the city. There they saw hearses and coffins in the air carrying to be buried. And there again, heaps of dead bodies lying unburied and the like, just as the imagination of the poor terrified people furnished them with matter to work upon.

So hypochondriac fancies representShips, armies, battles in the firmament;Till steady eyes the exhalations solve,And all to its first matter, cloud, resolve.I could fill this account with the strange relations such people give every day of what they have seen; and every one was so positive of their having seen what they pretended to see, that there was no contradicting them, without breach of friendship, or being accounted rude and unmannerly on the one hand, and profane and impenetrable on the other. One time before the plague was begun, otherwise than as I have said in St. Giles's (I think it was in March), seeing a crowd of people in the street, I joined with them to satisfy my curiosity, and found them all staring up into the air to see what a woman told them appeared plain to her, which was an angel clothed in white, with a fiery sword in his hand, waving it or brandishing it over his head. She described every part of the figure to the life, showed them the motion and the form, and the poor people came into it so eagerly and with so much readiness. "Yes, I see it all plainly," says one: "there's the sword as plain as can be." Another saw the angel; one saw his very face, and cried out what a glorious creature he was. One saw one thing, and one another. I looked as earnestly as the rest, but perhaps not with so much willingness to be imposed upon; and I said, indeed, that I could see nothing but a white cloud, bright on one side, by the shining of the sun upon the other part. The woman endeavored to show it me, but could not make me confess that I saw it; which, indeed, if I had, I must have lied. But the woman, turning to me, looked me in the face, and fancied I laughed, in which her imagination deceived her too, for I really did not laugh, but was seriously reflecting how the poor people were terrified by the force of their own imagination. However, she turned to me, called me profane fellow and a scoffer, told me that it was a time of God's anger, and dreadful judgments were approaching, and that despisers such as I should wander and perish.

The people about her seemed disgusted as well as she, and I found there was no persuading them that I did not laugh at them, and that I should be rather mobbed by them than be able to undeceive them. So I left them, and this appearance passed for as real as the blazing star itself.

Another encounter I had in the open day also; and this was in going through a narrow passage from Petty France52 into Bishopsgate churchyard, by a row of almshouses. There are two churchyards to Bishopsgate Church or Parish. One we go over to pass from the place called Petty France into Bishopsgate Street, coming out just by the church door; the other is on the side of the narrow passage where the almshouses are on the left, and a dwarf wall with a palisade on it on the right hand, and the city wall on the other side more to the right.

In this narrow passage stands a man looking through the palisades into the burying place, and as many people as the narrowness of the place would admit to stop without hindering the passage of others; and he was talking mighty eagerly to them, and pointing, now to one place, then to another, and affirming that he saw a ghost walking upon such a gravestone there. He described the shape, the posture, and the movement of it so exactly, that it was the greatest amazement to him in the world that everybody did not see it as well as he. On a sudden he would cry, "There it is! Now it comes this way!" then, "'Tis turned back!" till at length he persuaded the people into so firm a belief of it, that one fancied he saw it; and thus he came every day, making a strange hubbub, considering it was so narrow a passage, till Bishopsgate clock struck eleven; and then the ghost would seem to start, and, as if he were called away, disappeared on a sudden.

I looked earnestly every way, and at the very moment that this man directed, but could not see the least appearance of anything. But so positive was this poor man that he gave them vapors53 in abundance, and sent them away trembling and frightened, till at length few people that knew of it cared to go through that passage, and hardly anybody by night on any account whatever.

This ghost, as the poor man affirmed, made signs to the houses and to the ground and to the people, plainly intimating (or else they so understanding it) that abundance of people should come to be buried in that churchyard, as indeed happened. But then he saw such aspects I must acknowledge I never believed, nor could I see anything of it myself, though I looked most earnestly to see it if possible.

Some endeavors were used to suppress the printing of such books as terrified the people, and to frighten the dispersers of them, some of whom were taken up, but nothing done in it, as I am informed; the government being unwilling to exasperate the people, who were, as I may say, all out of their wits already.

Neither can I acquit those ministers that in their sermons rather sunk than lifted up the hearts of their hearers. Many of them, I doubt not, did it for the strengthening the resolution of the people, and especially for quickening them to repentance; but it certainly answered not their end, at least not in proportion to the injury it did another way.

One mischief always introduces another. These terrors and apprehensions of the people led them to a thousand weak, foolish, and wicked things, which they wanted not a sort of people really wicked to encourage them to; and this was running about to fortune tellers, cunning men,54 and astrologers, to know their fortunes, or, as it is vulgarly expressed, to have their fortunes told them, their nativities55 calculated, and the like. And this folly presently made the town swarm with a wicked generation of pretenders to magic, to the "black art," as they called it, and I know not what, nay, to a thousand worse dealings with the devil than they were really guilty of. And this trade grew so open and so generally practiced, that it became common to have signs and inscriptions set up at doors, "Here lives a fortune teller," "Here lives an astrologer," "Here you may have your nativity calculated," and the like; and Friar Bacon's brazen head,56 which was the usual sign of these people's dwellings, was to be seen almost in every street, or else the sign of Mother Shipton,57 or of Merlin's58 head, and the like.

With what blind, absurd, and ridiculous stuff these oracles of the devil pleased and satisfied the people, I really know not; but certain it is, that innumerable attendants crowded about their doors every day: and if but a grave fellow in a velvet jacket, a band,59 and a black cloak, which was the habit those quack conjurers generally went in, was but seen in the streets, the people would follow them60 in crowds, and ask them60 questions as they went along.

The case of poor servants was very dismal, as I shall have occasion to mention again by and by; for it was apparent a prodigious number of them would be turned away. And it was so, and of them abundance perished, and particularly those whom these false prophets flattered with hopes that they should be kept in their services, and carried with their masters and mistresses into the country; and had not public charity provided for these poor creatures, whose number was exceeding great (and in all cases of this nature must be so), they would have been in the worst condition of any people in the city.

These things agitated the minds of the common people for many months while the first apprehensions were upon them, and while the plague was not, as I may say, yet broken out. But I must also not forget that the more serious part of the inhabitants behaved after another manner. The government encouraged their devotion, and appointed public prayers, and days of fasting and humiliation, to make public confession of sin, and implore the mercy of God to avert the dreadful judgment which hangs over their heads; and it is not to be expressed with what alacrity the people of all persuasions embraced the occasion, how they flocked to the churches and meetings, and they were all so thronged that there was often no coming near, even to the very doors of the largest churches. Also there were daily prayers appointed morning and evening at several churches, and days of private praying at other places, at all which the people attended, I say, with an uncommon devotion. Several private families, also, as well of one opinion as another, kept family fasts, to which they admitted their near relations only; so that, in a word, those people who were really serious and religious applied themselves in a truly Christian manner to the proper work of repentance and humiliation, as a Christian people ought to do.

Again, the public showed that they would bear their share in these things. The very court, which was then gay and luxurious, put on a face of just concern for the public danger. All the plays and interludes61 which, after the manner of the French court,62 had been set up and began to increase among us, were forbid to act;63 the gaming tables, public dancing rooms, and music houses, which multiplied and began to debauch the manners of the people, were shut up and suppressed; and the jack puddings,64 merry-andrews,64 puppet shows, ropedancers, and such like doings, which had bewitched the common people, shut their shops, finding indeed no trade, for the minds of the people were agitated with other things, and a kind of sadness and horror at these things sat upon the countenances even of the common people. Death was before their eyes, and everybody began to think of their graves, not of mirth and diversions.

But even these wholesome reflections, which, rightly managed, would have most happily led the people to fall upon their knees, make confession of their sins, and look up to their merciful Savior for pardon, imploring his compassion on them in such a time of their distress, by which we might have been as a second Nineveh, had a quite contrary extreme in the common people, who, ignorant and stupid in their reflections as they were brutishly wicked and thoughtless before, were now led by their fright to extremes of folly, and, as I said before, that they ran to conjurers and witches and all sorts of deceivers, to know what should become of them, who fed their fears and kept them always alarmed and awake, on purpose to delude them and pick their pockets: so they were as mad upon their running after quacks and mountebanks, and every practicing old woman for medicines and remedies, storing themselves with such multitudes of pills, potions, and preservatives, as they were called, that they not only spent their money, but poisoned themselves beforehand, for fear of the poison of the infection, and prepared their bodies for the plague, instead of preserving them against it. On the other hand, it was incredible, and scarce to be imagined, how the posts of houses and corners of streets were plastered over with doctors' bills, and papers of ignorant fellows quacking and tampering in physic, and inviting people to come to them for remedies, which was generally set off with such flourishes as these; viz., "Infallible preventitive pills against the plague;" "Never-failing preservatives against the infection;" "Sovereign cordials against the corruption of air;" "Exact regulations for the conduct of the body in case of infection;" "Antipestilential pills;" "Incomparable drink against the plague, never found out before;" "An Universal remedy for the plague;" "The Only True plague water;" "The Royal Antidote against all kinds of infection;" and such a number more that I cannot reckon up, and, if I could, would fill a book of themselves to set them down.

Others set up bills to summon people to their lodgings for direction and advice in the case of infection. These had specious titles also, such as these: —

An eminent High-Dutch physician, newly come over from Holland, where he resided during all the time of the great plague, last year, in Amsterdam, and cured multitudes of people that actually had the plague upon them.

An Italian gentlewoman just arrived from Naples, having a choice secret to prevent infection, which she found out by her great experience, and did wonderful cures with it in the late plague there, wherein there died 20,000 in one day.

An ancient gentlewoman having practiced with great success in the late plague in this city, anno 1636, gives her advice only to the female sex. To be spoken with, etc.

An experienced physician, who has long studied the doctrine of antidotes against all sorts of poison and infection, has, after forty years' practice, arrived at such skill as may, with God's blessing, direct persons how to prevent being touched by any contagious distemper whatsoever. He directs the poor gratis.

I take notice of these by way of specimen. I could give you two or three dozen of the like, and yet have abundance left behind. It is sufficient from these to apprise any one of the humor of those times, and how a set of thieves and pickpockets not only robbed and cheated the poor people of their money, but poisoned their bodies with odious and fatal preparations; some with mercury, and some with other things as bad, perfectly remote from the thing pretended to, and rather hurtful than serviceable to the body in case an infection followed.

I cannot omit a subtlety of one of those quack operators with which he gulled the poor people to crowd about him, but did nothing for them without money. He had, it seems, added to his bills, which he gave out in the streets, this advertisement in capital letters; viz., "He gives advice to the poor for nothing."

Abundance of people came to him accordingly, to whom he made a great many fine speeches, examined them of the state of their health and of the constitution of their bodies, and told them many good things to do, which were of no great moment. But the issue and conclusion of all was, that he had a preparation which, if they took such a quantity of every morning, he would pawn his life that they should never have the plague, no, though they lived in the house with people that were infected. This made the people all resolve to have it, but then the price of that was so much (I think it was half a crown65). "But, sir," says one poor woman, "I am a poor almswoman, and am kept by the parish; and your bills say you give the poor your help for nothing." – "Ay, good woman," says the doctor, "so I do, as I published there. I give my advice, but not my physic!" – "Alas, sir," says she, "that is a snare laid for the poor then, for you give them your advice for nothing; that is to say, you advise them gratis to buy your physic for their money: so does every shopkeeper with his wares." Here the woman began to give him ill words, and stood at his door all that day, telling her tale to all the people that came, till the doctor, finding she turned away his customers, was obliged to call her upstairs again and give her his box of physic for nothing, which perhaps, too, was good for nothing when she had it.

But to return to the people, whose confusions fitted them to be imposed upon by all sorts of pretenders and by every mountebank. There is no doubt but these quacking sort of fellows raised great gains out of the miserable people; for we daily found the crowds that ran after them were infinitely greater, and their doors were more thronged, than those of Dr. Brooks, Dr. Upton, Dr. Hodges, Dr. Berwick, or any, though the most famous men of the time; and I was told that some of them got five pounds66 a day by their physic.

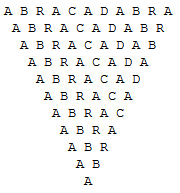

But there was still another madness beyond all this, which may serve to give an idea of the distracted humor of the poor people at that time, and this was their following a worse sort of deceivers than any of these; for these petty thieves only deluded them to pick their pockets and get their money (in which their wickedness, whatever it was, lay chiefly on the side of the deceiver's deceiving, not upon the deceived); but, in this part I am going to mention, it lay chiefly in the people deceived, or equally in both. And this was in wearing charms, philters,67 exorcisms,68 amulets,69 and I know not what preparations to fortify the body against the plague, as if the plague was not the hand of God, but a kind of a possession of an evil spirit, and it was to be kept off with crossings,70 signs of the zodiac,71 papers tied up with so many knots, and certain words or figures written on them, as particularly the word "Abracadabra,"72 formed in triangle or pyramid; thus, —

Others had the Jesuits' mark in a cross: —

I H

S73

Others had nothing but this mark; thus, —

+

I might spend a great deal of my time in exclamations against the follies, and indeed the wickednesses of those things, in a time of such danger, in a matter of such consequence as this of a national infection; but my memorandums of these things relate rather to take notice of the fact, and mention only that it was so. How the poor people found the insufficiency of those things, and how many of them were afterwards carried away in the dead carts, and thrown into the common graves of every parish with these hellish charms and trumpery hanging about their necks, remains to be spoken of as we go along.

All this was the effect of the hurry the people were in, after the first notion of the plague being at hand was among them, and which may be said to be from about Michaelmas,74 1664, but more particularly after the two men died in St. Giles's, in the beginning of December; and again after another alarm in February, for when the plague evidently spread itself, they soon began to see the folly of trusting to these unperforming creatures who had gulled them of their money; and then their fears worked another way, namely, to amazement and stupidity, not knowing what course to take or what to do, either to help or to relieve themselves; but they ran about from one neighbor's house to another, and even in the streets, from one door to another, with repeated cries of, "Lord, have mercy upon us! What shall we do?"