The Treaty of Waitangi; or, how New Zealand became a British Colony

We have heard that the tribe of Marian8 is at hand coming to take away our land, therefore we pray thee to become our friend and guardian of these Islands, lest through the teazing of other tribes should come war to us, and lest strangers should come and take away our land. And if any of thy people should be troublesome or vicious towards us (for some persons are living here who have run away from ships), we pray thee to be angry with them that they may be obedient, lest the anger of the people of this land fall upon them.

This letter is from us the chiefs of the natives of New Zealand:

The accumulating reports of increasing disorder, the strenuous recommendations of Governor Bourke, added to the touching appeal of the chiefs, at length moved the Colonial Office to acquiesce in the contention that some one should be sent to New Zealand directly charged with the duty of representing the British Crown. In replying to the Native petition, Lord Goderich,9 who was then at the Colonial Office, after expressing the gratification the petition had afforded the King, accordingly intimated that it had been decided to appoint as British Resident Mr. James Busby, whose duty it would be to investigate all complaints which might be made to him. "It will also be his endeavour," wrote his Lordship, "to prevent the arrival amongst you of men who have been guilty of crimes in their own country, and who may effect their escape from the place to which they have been banished, as likewise to apprehend such persons of this description who may be found at present at large. In return for the anxious desire which will be manifested by the British Resident to afford his protection to the inhabitants of New Zealand, against any acts of outrage which may be attempted against them by British subjects, it is confidently expected by His Majesty that on your part you will render to the British Resident that assistance and support which are calculated to promote the objects of his appointment, and to extend to your country all the benefits which it is capable of receiving from its friendship and alliance with Great Britain."

Mr. Busby, who had thus been chosen for the responsible task of guarding both British and Native interests, was the son of a successful civil engineer in Australia, but it is doubtful whether he had passed through the administrative experience necessary to fit him in all respects for his arduous post.10 His position was rendered still more difficult by reason of the fact that, much as Ministers might have wished to do so, it had been found impossible to sweep away the constitutional difficulties which faced them on every side. Indeed so hampered was the situation by the circumstance that Britain had not acquired, or claimed Sovereign rights in New Zealand, that when Governor Bourke came to direct Mr. Busby upon the scope of his office, he was compelled to lay greater stress upon the things he could not do, than upon the powers he was at liberty to exercise.

Mr. Busby was instructed to leave Sydney by H.M.S. Imogene, commanded by Captain Blackwood, and on arrival at the Bay of Islands he was to present to the chiefs the King's reply to their petition, "with as much formality as circumstances may permit." This instruction Mr. Busby used his best endeavours to obey, for after a stormy passage across the Tasman Sea he reached the Bay of Islands on Sunday, May 5, 1833. Here he at once made arrangements with the settlers and Missionaries to invest his landing with an importance which was its due; but continued storms made it impossible to perform any kind of open-air ceremony with comfort and dignity until the 17th. On that day, however, the weather had moderated, and at an early hour preparations were afoot for the inevitable feast, a proclivity to which both Maori and European appear equally addicted. At a later hour Mr. Busby, accompanied by the first lieutenant of the Imogene, landed under a salute of seven guns, and no sooner had he set foot on shore than he was claimed by the old chief, Tohitapu, as his Pakeha. A cordial greeting awaited the Resident by the Missionaries, to whose village at Paihia, but a short distance off, the party at once adjourned. Here three hoary-headed chiefs delivered speeches of welcome, a haka was danced, and still more speeches were made in honour of a stranger whose coming was regarded as the event of first importance since the landing of Samuel Marsden seventeen years before. With these evidences of native hospitality at an end, the formal proceedings were commenced in front of the little mission chapel round which the people crowded in motley throng, shouting songs of welcome, and discharging fitful volleys of musketry. By dint of lively exertion order was at length restored, and standing at a table, with Captain Blackwood on his right and Mr. Henry Williams, who interpreted, on his left, Mr. Busby read the King's reply to the people's Petition for protection. The reading of this document was listened to with profound respect by the Europeans, who rose and uncovered their heads, while the natives hung upon the words of Mr. Williams as he explained the professions of the King's good-will, of the sincerity of which Mr. Busby was a living evidence. Then followed Mr. Busby's own address, which was listened to by the wondering crowd with no less rapt attention:

My Friends – You will perceive by the letter which I have been honoured with the commands of the King of Great Britain to deliver to you, that it is His Majesty's most anxious wish that the most friendly feeling should subsist between his subjects and yourselves, and how much he regrets that you should have cause to complain of the conduct of any of his subjects. To foster and maintain this friendly feeling, to prevent as much as possible the recurrence of those misunderstandings and quarrels which have unfortunately taken place, and to give a greater assurance of safety and just dealing both to his own subjects and the people of New Zealand in their commercial transactions with each other, these are the purposes for which His Majesty has sent me to reside amongst you, and I hope and trust that when any opportunities of doing a service to the people of this country shall arise I shall be able to prove to you how much it is my own desire to be the friend of those amongst whom I am come to reside. It is the custom of His Majesty the King of Great Britain to send one or more of his servants to reside as his representatives in all those countries in Europe and America with which he is on terms of friendship, and in sending one of his servants to reside amongst the chiefs of New Zealand, they ought to be sensible not only of the advantages which will result to the people of New Zealand by extending their commercial intercourse with the people of England, but of the honour the King of a great and powerful nation like Great Britain has done their country in adopting it into the number of those countries with which he is in friendship and alliance. I am, however, commanded to inform you that in every country to which His Majesty sends his servants to reside as his representatives, their persons and their families, and all that belongs to them are considered sacred. Their duty is the cultivation of peace and friendship and goodwill, and not only the King of Great Britain, but the whole civilised world would resent any violence which his representative might suffer in any of the countries to which they are sent to reside in his name. I have heard that the chiefs and people of New Zealand have proved the faithful friends of those who have come among them to do them good, and I therefore trust myself to their protection and friendship with confidence. All good Englishmen are desirous that the New Zealanders should be a rich and happy people, and it is my wish when I shall have erected my house that all the chiefs will come and visit me and be my friends. We will then consult together by what means they can make their country a flourishing country, and their people a rich and wise people like the people of Great Britain. At one time Great Britain differed but little from what New Zealand is now. The people had no large houses nor good clothing nor good food. They painted their bodies and clothed themselves with the skins of wild beasts; every chief went to war with his neighbour, and the people perished in the wars of their chiefs even as the people of New Zealand do now. But after God sent His Son into the world to teach mankind that all the tribes of the earth are brethren, and that they ought not to hate and destroy, but to love and do good to one another, and when the people of England learned His words of wisdom, they ceased to go to war against each other, and all the tribes became one people. The peaceful inhabitants of the country began to build large houses because there was no enemy to pull them down. They cultivated their land and had abundance of bread, because no hostile tribe entered into their fields to destroy the fruit of their labours. They increased the numbers of their cattle because no one came to drive them away. They also became industrious and rich, and had all good things they desired. Do you then, O chiefs and tribes of New Zealand, desire to become like the people of England? Listen first to the Word of God which He has put into the hearts of His servants the missionaries to come here and teach you. Learn that it is the will of God that you should all love each other as brethren, and when wars shall cease among you then shall your country flourish. Instead of the roots of the fern you shall eat bread, because the land shall be tilled without fear, and its fruits shall be eaten in peace. When there is an abundance of bread we shall labour to preserve flax and timber and provisions for the ships which come to trade, and the ships that come to trade will bring clothing and all other things which you desire. Thus you become rich, for there are no riches without labour, and men will not labour unless there is peace, that they may enjoy the fruits of their labour.

The Resident's address was received with an outburst of wild applause, and soon the smoke of discharging muskets again hung heavy on the morning air. But there was still other diversion for the natives, to whom the proceedings had proved a great novelty. The mental feast which was to provide them with food for discussion for many days was now supplanted by a more material repast, at which fifty settlers were entertained at Mr. Williams's house, while the Maoris were fed with a sumptuousness that made memorable to them the coming and the installation of the first British Resident.

As an adjunct to his slender authority, Mr. Busby had been informed by Governor Bourke that Sir John Gore, the Vice-Admiral commanding the Indian Squadron of the Navy, would be instructed to permit his ships to call in at New Zealand ports as frequently as possible, and offer him what support they could during these fitful visits. But upon neither naval nor civil power was Mr. Busby to rely overmuch. He was to depend for his authority rather upon his moral influence and his co-operation with the Missionaries, to whom he went specially accredited.

Mr. Busby has frequently been made the butt of the humorist, because his bark was necessarily worse than his bite. The Maori cynic of his day chuckled as he dubbed him "He manuwa pu kore" ("A man-of-war without guns"), and many a playful jest has since been made at his expense, all of which is both unfair and ungenerous to Mr. Busby. The difficulty in the way of investing him with legal power was thus tersely explained by Sir Richard Bourke during the course of his initial instructions to the Resident:

You are aware that you cannot be clothed with any legal power or jurisdiction, by virtue of which you might be enabled to arrest British subjects offending against British or Colonial law in New Zealand. It was proposed to supply this want of power and to provide further enforcement of the criminal law as it exists amongst ourselves, and further to adapt it to the new and peculiar exigencies of the country to which you are going, by means of a Colonial Act of Council grafted on a statute of the Imperial Parliament. Circumstances which I am not at present competent to explain have prevented the enactment of the Statute in question.11 You can therefore rely but little on the force of law, and must lay the foundation of your measures upon the influence which you shall obtain over the Native Chiefs. Something, however, may be effected under the law as it stands at present. By the 9th Geo. IV., cap. 83, sec. A, the Supreme Courts of N. S. Wales and Van Dieman's Land have power to enquire of, hear and determine, all offences committed in N.Z. by the Master and crew of any British ship or vessel, or by any British subject living there, and persons convicted of such offences may be punished as if the offence has been committed in England… If therefore you should at any time have the means of sending to this colony any one or more persons capable of lodging an information before the proper authorities here, of an offence committed in N.Z. you will, if you think the case of sufficient magnitude and importance, send a detailed report of the transaction to the Colonial Secretary by such persons who will be required to depose to the facts sufficient to support an information upon which a bench Warrant may be obtained from the Supreme Court for the apprehension of the offender, and transmitted to you for execution. You will perceive at once that this process, which is at best a prolix and inconvenient operation and may incur some considerable expense, will be totally useless unless you should have some well-founded expectation of securing the offender upon or after the arrival of the warrant, and of being able to effect his conveyance here for trial, and that you have provided the necessary evidence to ensure his conviction.

Shorn of everything which suggested practical power, except the name of British Resident, Mr. Busby soon found himself in no very enviable position. He was ignored by the whites and laughed at by the natives. To add still further to his difficulties he was slow to recognise that the Missionaries in the long years of their labour had naturally acquired more influence with the natives than he could possibly have, and he was reluctant to achieve his object by appearing to play a subordinate part to them. He had been explicitly instructed to seek their hearty co-operation, and take every advantage of the high respect in which they were held by the natives. It was not long, however, before he began to develop ideas of his own and to formulate a policy which he could not enforce, because it was at variance with that of the Missions.

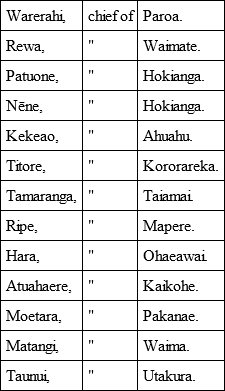

He had also been accredited to the thirteen chiefs who had signed the memorial to the King in the previous year, and had been advised to seek their assistance in arresting those offenders whom he had power to transmit to Sydney for trial. The number of such persons whom he might have apprehended now totalled, we are assured, to several hundreds; but the process was, as Sir Richard Bourke had suggested, so obviously "prolix and inconvenient," that Mr. Busby exercised to the full the measure of discretion given him by the Governor, and left them severely alone.12

According to Captain Fitzroy, who visited the Bay of Islands during the cruise of H.M.S. Beagle in 1835, he preferred to fold his hands and allow events to shape their own course. "He chose to tell every one who went to him that he had no authority; that he was not even allowed to act as a Magistrate, and that he could do nothing. The consequence was that whenever anything did occur, those who were aggrieved went to the Missionaries. Mr. Busby might have very considerable power, because the Missionaries have such influence over the whole body of natives they could support him. If Mr. Busby wanted a person taken up he had only to express his wish to the Missionaries, and the natives would have done it for them, but he was slow to act in that way. He was sent there in a high character, and was accredited to the Missionaries, and had he communicated with them freely and allowed them to be cognisant of, if not the agents in all that took place, while he remained as the head, and the understanding had been that all that the Missionaries did was done in concert with Mr. Busby, and all that eventuated was from him as the head, his influence would have been far too great for any individuals in that part of the Islands to resist. By dividing the two influences Mr. Busby lost his power of preventing mischief. He remained on tolerably good terms with them, but separated himself in an unnecessary degree from them, and thought he might differ from them sometimes, even to taking a precisely opposite course of conduct to that which they recommended. The consequences were that while the natives retained their opinion of the Missionaries, they found that the Resident was a nonentity, and that he was there to look on and nothing more."

As illustrating the class of difference which sometimes arose between the Resident and the Missionaries, and which must have appreciably hampered the activities of both, Captain Fitzroy stated to the Committee of the House of Lords that when he was at the Bay of Islands in 1835 there was then a serious difference between the real and the nominal head of the community, with respect to the stopping or discouraging the sale of ardent spirits. The Missionaries wanted to carry into effect a regulation similar to one established in the Society Islands, namely, that no spirits should be imported into the country. Mr. Busby would not be a party to such a rule, contending that it was an unnecessary measure; while the Missionaries, on the other hand, were unanimous in declaring it was one of the most useful precautions they could take, but no amount of argument could induce Mr. Busby to co-operate with them.13

Mr. Busby at all times expressed the most profound respect for the Missionaries and veneration for their labours. He also cheerfully acknowledged that if the British Government expected them to accord their influence to its Representative they must be given a specified share in the government of the country. But when it came to a point of difference, he plainly let it be known that he considered himself possessed of a sounder judgment than they. After detailing to Governor Bourke a discussion in which he claimed to have got the better of the Missionaries, he wrote: "I thought they would naturally conclude in future that it was possible for the conclusions of a single mind, when directed to one object, to be more correct than the collective opinions of many persons whose minds are altogether engrossed with the multitude of details which fill up the attention of men, occupied as they are, leaving neither leisure nor capacity for more enlarged and comprehensive views."

Mr. Busby might have said more in fewer words, but he could scarcely have depreciated the mental powers of the Missionaries in a more delightfully prolix sentence. Skilfully, however, as the sting was sheathed within a cloud of words, the barb came through, with the not unnatural result that he had to confess the Missionaries afterwards neither respected his opinions nor appeared anxious to co-operate with him in what he described as "the furtherance of matters connected with the King's service in this country."

Though severely handicapped by his inability to coordinate his ideas with those of the Missionaries, or to sink his individuality before theirs, it does not follow that Mr. Busby was entirely idle. He lent himself with considerable industry to the task of placing the shipping of the country upon a basis more satisfactory than it had up to that time been. At the date of his arrival there were a number of New Zealand owned craft trading on our coasts, and several vessels were building on the Hokianga River. Sailing as these vessels were under no recognised register, and without the protection of the British ensign, which they were prohibited from hoisting, they were liable to seizure at any time by any enterprising pirate.14 Equally impossible was it for these owners to register their craft in New Zealand, for there was as yet no acknowledged flag of the nation.

These facts were made the subject of representation by Mr. Busby to the Governor of New South Wales, who accorded a hearty approval to his suggestion that the commerce of the country warranted some protection of this nature. Flags of three separate designs were accordingly entrusted to Captain Lambert of H.M.S. Alligator, who brought them from Sydney and submitted them to the chiefs for approval.

This event took place at Waitangi, on March 20, 1834, the natives having been gathered from all the surrounding pas into a large marquee erected in front of the British Residency, and gaily decorated with flags from the Alligator. Wisely or unwisely the proceedings were not conducted upon the democratic basis of our present-day politics; for upon some principle which has not been made clear the tent was divided by a barrier into two areas, into one of which only the rangatiras were admitted, and to them the right of selection was confined. No debate was permitted, but Mr. Busby read to the chiefs a speech in which he dwelt upon the advantages to be anticipated from the adoption of a national flag, and then invited them to take a vote for the choice of design.

This mode of procedure created considerable dissatisfaction amongst the plutocracy of the tribes, who resented the doubtful privilege of being permitted to look on without the consequential right to exercise their voice. The stifling of discussion also tended to breed distrust in the minds of some of the chiefs, to whom the settlement of so important a matter without a korero15 was a suspicious innovation. Two of the head men declined to record their votes, believing that under a ceremony conducted in such a manner there must be concealed some sinister motive. Despite these protests, the British Resident and Captain Lambert had their way, and at the conclusion of Mr. Busby's address, the flags were displayed and the electors invited to vote. The great warrior chief Hongi, acting as poll-clerk, took down in writing the preference of each chief. Twelve votes were recorded for the most popular ensign, ten for the next in favour, and six only for the third. It was then found that the choice of the majority had fallen upon the flag with a white ground divided by St. George's Cross, the upper quarter of which was again divided by St. George's cross, a white star on a blue field appearing in each of the smaller squares.16

The election over, the rejected flags were close furled, and the selected ensign flung out to the breeze beside the Union Jack of Old England.

In the name of the chiefs Mr. Busby declared the ensign to be the national flag of New Zealand. As the symbol of the new-born nation was run up upon the halyards, it was received with a salute of twenty-one guns from the warship Alligator, and by cheers from her officers and the goodly crowd of sailors, settlers, and Missionaries who had assembled to participate in the ceremony.

As is usual with most such functions where Britons are concerned, the event was celebrated by a feast. The Europeans were regaled at a cold luncheon at Mr. Busby's house, while the Maoris had pork, potatoes, and kororirori17 served upon the lawn in front of the Residency, which delicacies they devoured sans knives sans forks.

These proceedings subsequently received on behalf of the British Government the entire approbation of Lord Aberdeen;18 and the countenance thus lent to what at the time was regarded as no more than a protection to the commerce of the country was discovered to have a most important bearing upon the question of Britain's sovereignty over these islands.

Though Mr. Busby found himself destitute of legal power or military force to make good his authority, and equally lacking in the tact necessary to secure by policy what he could not achieve by any other means, he was sincerely and even enthusiastically loyal to the main principle underlying his office – the preservation of British interests. Thus when the tidings came that Baron de Thierry intended to set up his kingdom at Hokianga, he took immediate and, as far as lay in his power, effective steps to defeat what he regarded as a wanton piece of French aggression.