The Life of John Marshall (Volume 2 of 4)

But the Republicans would have none of it. After an acrid debate and in spite of personal appeals made to the members of the House, the substitute was defeated by a majority of three votes. John Marshall was the busiest and most persistent of Washington's friends, and of course voted for the substitute,447 which, almost certainly, he drew. Cold as was the original address which the Federalists had failed to amend, the Republicans now made it still more frigid. They would not admit that Washington deserved well of the whole country. They moved to strike out the word "country" and in lieu thereof insert "native state."448

Many years afterward Marshall told Justice Story his recollection of this bitter fight: "In the session of 1796 … which," said Marshall, "called forth all the strength and violence of party, some Federalist moved a resolution expressing the high confidence of the House in the virtue, patriotism, and wisdom of the President of the United States. A motion was made to strike out the word wisdom. In the debate the whole course of the Administration was reviewed, and the whole talent of each party was brought into action. Will it be believed that the word was retained by a very small majority? A very small majority in the legislature of Virginia acknowledged the wisdom of General Washington!"449

Dazed for a moment, the Federalists did not resist. But, their courage quickly returning, they moved a brief amendment of twenty words declaring that Washington's life had been "strongly marked by wisdom, in the cabinet, by valor, in the field, and by the purest patriotism in both." Futile effort! The Republicans would not yield. By a majority of nine votes450 they flatly declined to declare that Washington had been wise in council, brave in battle, or patriotic in either; and the original address, which, by these repeated refusals to endorse either Washington's sagacity, patriotism, or even courage, had now been made a dagger of ice, was sent to Washington as the final comment of his native State upon his lifetime of unbearable suffering and incalculable service to the Nation.

Arctic as was this sentiment of the Virginia Republicans for Washington, it was tropical compared with the feeling of the Republican Party toward the old hero as he retired from the Presidency. On Monday, March 5, 1797, the day after Washington's second term expired, the principal Republican newspaper of America thus expressed the popular sentiment: —

"'Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, for mine eyes have seen thy salvation,' was the pious ejaculation of a man who beheld a flood of happiness rushing in upon mankind…

"If ever there was a time that would license the reiteration of the exclamation, that time is now arrived, for the man [Washington] who is the source of all the misfortunes of our country, is this day reduced to a level with his fellow citizens, and is no longer possessed of power to multiply evils upon the United States.

"If ever there was a period for rejoicing this is the moment – every heart, in unison with the freedom and happiness of the people ought to beat high with exultation, that the name of Washington from this day ceases to give a currency to political iniquity, and to legalize corruption…

"A new æra is now opening upon us, an æra which promises much to the people; for public measures must now stand upon their own merits, and nefarious projects can no longer be supported by a name.

"When a retrospect is taken of the Washingtonian administration for eight years, it is a subject of the greatest astonishment, that a single individual should have cankered the principles of republicanism in an enlightened people, just emerged from the gulph of despotism, and should have carried his designs against the public liberty so far as to have put in jeopardy its very existence.

"Such however are the facts, and with these staring us in the face, this day ought to be a Jubilee in the United States."451

Such was Washington's greeting from a great body of his fellow citizens when he resumed his private station among them after almost twenty years of labor for them in both war and peace. Here rational imagination must supply what record does not reveal. What must Marshall have thought? Was this the fruit of such sacrifice for the people's welfare as no other man in America and few in any land throughout all history had ever made – this rebuke of Washington – Washington, who had been the soul as well as the sword of the Revolution; Washington, who alone had saved the land from anarchy; Washington, whose level sense, far-seeing vision, and mighty character had so guided the newborn Government that the American people had taken their place as a separate and independent Nation? Could any but this question have been asked by Marshall?

He was not the only man to whom such reflections came. Patrick Henry thus expressed his feelings: "I see with concern our old commander-in-chief most abusively treated – nor are his long and great services remembered… If he, whose character as our leader during the whole war, was above all praise, is so roughly handled in his old age, what may be expected by men of the common standard of character?"452

And Jefferson! Had he not become the voice of the majority?

Great as he was, restrained as he had arduously schooled himself to be, Washington personally resented the brutal assaults upon his character with something of the fury of his unbridled youth: "I had no conception that parties would or even could go to the length I have been witness to; nor did I believe, until lately, that it was within the bounds of probability – hardly within those of possibility – that … every act of my administration would be tortured and the grossest and most insidious misrepresentations of them be made … and that too in such exaggerated and indecent terms as could scarcely be applied to a Nero – a notorious defaulter – or even to a common pickpocket."453

Here, then, once more, we clearly trace the development of that antipathy between Marshall and Jefferson, the seeds of which were sown in those desolating years from 1776 to 1780, and in the not less trying period from the close of the Revolution to the end of Washington's Administration. Thus does circumstance mould opinion and career far more than abstract thinking; and emotion quite as much as reason shape systems of government. The personal feud between Marshall and Jefferson, growing through the years and nourished by events, gave force and speed to their progress along highways which, starting at the same point, gradually diverged and finally ran in opposite directions.

CHAPTER V

THE MAN AND THE LAWYER

Tall, meagre, emaciated, his muscles relaxed, his joints loosely connected, his head small, his complexion swarthy, his countenance expressing great good humor and hilarity. (William Wirt.)

Mr. Marshall can hardly be regarded as a learned lawyer. (Gustavus Schmidt.)

His head is one of the best organized of any I have known. (Rufus King.)

On a pleasant summer morning when the cherries were ripe, a tall, ungainly man in early middle life sauntered along a Richmond street. His long legs were encased in knee breeches, stockings, and shoes of the period; and about his gaunt, bony frame hung a roundabout or short linen jacket. Plainly, he had paid little attention to his attire. He was bareheaded and his unkempt hair was tied behind in a queue. He carried his hat under his arm, and it was full of cherries which the owner was eating as he sauntered idly along.454 Mr. Epps's hotel (The Eagle) faced the street along which this negligently appareled person was making his leisurely way. He greeted the landlord as he approached, cracked a joke in passing, and rambled on in his unhurried walk.

At the inn was an old gentleman from the country who had come to Richmond where a lawsuit, to which he was a party, was to be tried. The venerable litigant had a hundred dollars to pay to the lawyer who should conduct the case, a very large fee for those days. Who was the best lawyer in Richmond, asked he of his host? "The man who just passed us, John Marshall by name," said the tavern-keeper. But the countryman would have none of Marshall. His appearance did not fill the old man's idea of a practitioner before the courts. He wanted, for his hundred dollars, a lawyer who looked like a lawyer. He would go to the court-room itself and there ask for further recommendation. But again he was told by the clerk of the court to retain Marshall, who, meanwhile, had ambled into the court-room.

But no! This searcher for a legal champion would use his own judgment. Soon a venerable, dignified person, solemn of face, with black coat and powdered wig, entered the room. At once the planter retained him. The client remained in the court-room, it appears, to listen to the lawyers in the other cases that were ahead of his own. Thus he heard the pompous advocate whom he had chosen; and then, in astonishment, listened to Marshall.

The attorney of impressive appearance turned out to be so inferior to the eccentric-looking advocate that the planter went to Marshall, frankly told him the circumstances, and apologized. Explaining that he had but five dollars left, the troubled old farmer asked Marshall whether he would conduct his case for that amount. With a kindly jest about the power of a black coat and a powdered wig, Marshall good-naturedly accepted.455

This not too highly colored story is justified by all reports of Marshall that have come down to us. It is some such picture that we must keep before us as we follow this astonishing man in the henceforth easy and giant, albeit accidental, strides of his great career. John Marshall, after he had become the leading lawyer of Virginia, and, indeed, throughout his life, was the simple, unaffected man whom the tale describes. Perhaps consciousness of his own strength contributed to his disregard of personal appearance and contempt for studied manners. For Marshall knew that he carried heavier guns than other men. "No one," says Story, who knew him long and intimately, "ever possessed a more entire sense of his own extraordinary talents … than he."456

Marshall's most careful contemporary observer, William Wirt, tells us that Marshall was "in his person, tall, meagre, emaciated; his muscles relaxed and his joints so loosely connected, as not only to disqualify him, apparently, for any vigorous exertion of body, but to destroy everything like elegance and harmony in his air and movements.

"Indeed, in his whole appearance, and demeanour; dress, attitudes, gesture; sitting, standing, or walking; he is as far removed from the idolized graces of lord Chesterfield, as any other gentleman on earth.

"To continue the portrait; his head and face are small in proportion to his height; his complexion swarthy; the muscles of his face being relaxed; … his countenance has a faithful expression of great good humour and hilarity; while his black eyes – that unerring index – possess an irradiating spirit which proclaims the imperial powers of the mind that sits enthroned within…

"His voice is dry, and hard; his attitude, in his most effective orations, often extremely awkward; as it was not unusual for him to stand with his left foot in advance, while all his gesture proceeded from his right arm, and consisted merely in a vehement, perpendicular swing of it from about the elevation of his head to the bar, behind which he was accustomed to stand."457

During all the years of clamorous happenings, from the great Virginia Convention of 1788 down to the beginning of Adams's Administration and in the midst of his own active part in the strenuous politics of the time, Marshall practiced his profession, although intermittently. However, during the critical three weeks of plot and plan, debate and oratory in the famous month of June, 1788, he managed to do some "law business": while Virginia's Constitutional Convention was in session, he received twenty fees, most of them of one and two pounds and the largest from "Colọ W. Miles Cary 6.4." He drew a deed for his fellow member of the Convention, James Madison, while the Convention was in session, for which he charged his colleague one pound and four shillings.

But there was no time for card-playing during this notable month and no whist or backgammon entries appear in Marshall's Account Book. Earlier in the year we find such social expenses as "Card table 5.1 °Cards 8/ paper 2/-6" and "expenses and loss at billiards at dift times 3" (pounds). In September, 1788, occurs the first entry for professional literature, "Law books 20/-1"; but a more important book purchase was that of "Mazai's book sur les etats unis458 18" (shillings), an entry which shows that some of Marshall's family could read French.459

Marshall's law practice during this pivotal year was fairly profitable. He thus sums up his earnings and outlay, "Recḍ in the year 1788 1169.05; and expended in year 1788, 515-13-7" which left Marshall more than 653 pounds or about $1960 Virginia currency clear profit for the year.460

The following year (1789) he did a little better, his net profit being a trifle over seven hundred pounds, or about $2130 Virginia currency. In 1790 he earned a few shillings more than 1427 pounds and had about $2400 Virginia currency remaining, after paying all expenses. In 1791 he did not do so well, yet he cleared over $2200 Virginia currency. In 1792 his earnings fell off a good deal, yet he earned more than he expended, over 402 pounds (a little more than $1200 Virginia currency).

In 1793 Marshall was slightly more successful, but his expenses also increased, and he ended this year with a trifle less than 400 pounds clear profit. He makes no summary in 1794, but his Account Book shows that he no more than held his own. This business barometer does not register beyond the end of 1795,461 and there is no further evidence than the general understanding current in Richmond as to the amount of his earnings after this date. La Rochefoucauld reported in 1797 that "Mr. Marshall does not, from his practice, derive above four or five thousand dollars per annum and not even that sum every year."462 We may take this as a trustworthy estimate of Marshall's income; for the noble French traveler and student was thorough in his inquiries and took great pains to verify his statements.

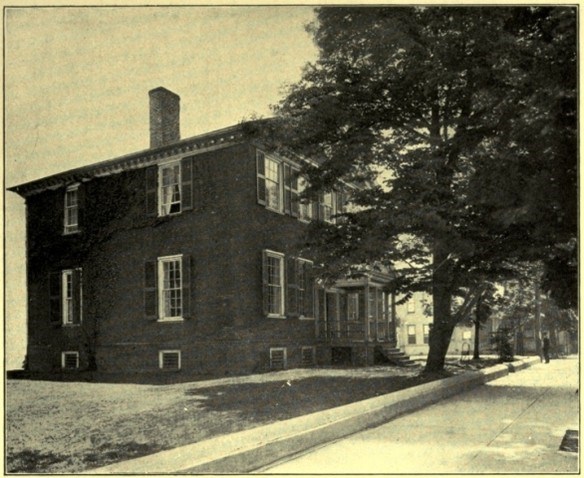

In 1789 Marshall bought the tract of land amounting to an entire city "square" of two acres,463 on which, four years later, he built the comfortable brick residence where he lived, while in Richmond, during the remainder of his life. This house still stands (1916) and is in excellent repair. It contains nine rooms, most of them commodious, and one of them of generous dimensions where Marshall gave the "lawyer dinners" which, later, became so celebrated. This structure was one of a number of the important houses of Richmond.464 Near by were the residences of Colonel Edward Carrington, Daniel Call, an excellent lawyer, and George Fisher, a wealthy merchant; these men had married the three sisters of Marshall's wife. The house of Jacquelin Ambler was also one of this cluster of dwellings. So that Marshall was in daily association with four men to whom he was related by marriage, a not negligible circumstance; for every one of them was a strong and successful man, and all of them were, like Marshall, pronounced Federalists. Their views and tastes were the same, they mutually aided and supported one another; and Marshall was, of course, the favorite of this unusual family group.

In the same locality lived the Leighs, Wickhams, Ronalds, and others, who, with those just mentioned, formed the intellectual and social aristocracy of the little city.465 Richmond grew rapidly during the first two decades that Marshall lived there. From the village of a few hundred people abiding in small wooden houses, in 1783, the Capital became, in 1795, a vigorous town of six thousand inhabitants, dwelling mostly in attractive brick residences.466 This architectural transformation was occasioned by a fire which, in 1787, destroyed most of the buildings in Richmond.467 Business kept pace with the growth of the city, wealth gradually and healthfully accumulated, and the comforts of life appeared. Marshall steadily wove his activities into those of the developing Virginia metropolis and his prosperity increased in moderate and normal fashion.

JOHN MARSHALL'S HOUSE, RICHMOND

THE LARGE ROOM WHERE THE FAMOUS "LAWYERS' DINNERS" WERE GIVEN

In his personal business affairs Marshall showed a childlike faith in human nature which sometimes worked to his disadvantage. For instance, in 1790 he bought a considerable tract of land in Buckingham County, which was heavily encumbered by a deed of trust to secure "a debt of a former owner" of the land to Caron de Beaumarchais.468 Marshall knew of this mortgage "at the time of the purchase, but he felt no concern … because" the seller verbally "promised to pay the debt and relieve the land from the incumbrance."

So he made the payments through a series of years, in spite of the fact that Beaumarchais's mortgage remained unsatisfied, that Marshall urged its discharge, and, finally, that disputes concerning it arose. Perhaps the fact that he was the attorney of the Frenchman in important litigation quieted apprehension. Beaumarchais having died, his agent, unable to collect the debt, was about to sell the land under the trust deed, unless Marshall would pay the obligation it secured. Thus, thirteen years after this improvident transaction, Marshall was forced to take the absurd tangle into a court of equity.469

But he was as careful of matters entrusted to him by others as this land transaction would suggest that he was negligent of his own affairs. Especially was he in demand, it would seem, when an enterprise was to be launched which required public confidence for its success. For instance, the subscribers to a fire insurance company appointed him on the committee to examine the proposed plan of business and to petition the Legislature for a charter,470 which was granted under the name of the "Mutual Assurance Society of Virginia."471 Thus Marshall was a founder of one of the oldest American fire insurance companies.472 Again, when in 1792 the "Bank of Virginia," a State institution, was organized,473 Marshall was named as one of the committee to receive and approve subscriptions for stock.474

No man could have been more watchful than was Marshall of the welfare of members of his family. At one of the most troubled moments of his life, when greatly distressed by combined business and political complications,475 he notes a love affair of his sister and, unasked, carefully reviews the eligibility of her suitor. Writing to his brother James on business and politics, he says: —

"I understand that my sister Jane, while here [Richmond], was addressed by Major Taylor and that his addresses were encouraged by her. I am not by any means certain of the fact nor did I suspect it until we had separated the night preceding her departure and consequently I could have no conversation with her concerning it.

"I believe that tho' Major Taylor was attach'd to her, it would probably have had no serious result if Jane had not manifested some partiality for him. This affair embarrasses me a good deal. Major Taylor is a young gentleman of talents and integrity for whom I profess and feel a real friendship. There is no person with whom I should be better pleased if there were not other considerations which ought not to be overlook'd. Mr. Taylor possesses but little if any fortune, he is encumbered with a family, and does not like his profession. Of course he will be as eminent in his profession as his talents entitle him to be. These are facts unknown to my sister but which ought to be known to her.

"Had I conjectured that Mr. Taylor was contemplated in the character of a lover I shou'd certainly have made to her all proper communications. I regret that it was concealed from me. I have a sincere and real affection and esteem for Major Taylor but I think it right in affairs of this sort that the real situation of the parties should be mutually understood. Present me affectionately to my sister."476

From the beginning of his residence in Richmond, Marshall had been an active member of the Masonic Order. He had become a Free Mason while in the Revolutionary army,477 which abounded in camp lodges. It was due to his efforts as City Recorder of Richmond that a lottery was successfully conducted to raise funds for the building of a Masonic hall in the State Capital in 1785.478 The following year Marshall was appointed Deputy Grand Master. In 1792 he presided over the Grand Lodge as Grand Master pro tempore; and the next year he was chosen as the head of the order in Virginia. He was reëlected as Grand Master in 1794; and presided over the meetings of the Grand Lodge held during 1793 until 1795 inclusive. During the latter year the Masonic hall in Manchester was begun and he assisted in the ceremonies attending the laying of the corner-stone, which bore this inscription: "This stone was laid by the Worshipful Archibald Campbell, Master of the Manchester Lodge of free & accepted Masons Assisted by & in the presence of the Most Worshipful John Marshall Grand Master of Masons to Virginia."479

Upon the expiration of his second term in this office, the Grand Lodge "Resolved, that the Grand Lodge are truly sensible of the great attention of our late Grand Master, John Marshall, to the duties of Masonry, and that they entertain an high sense of the wisdom displayed by him in the discharge of the duties of his office; and as a token of their entire approbation of his conduct do direct the Grand Treasurer to procure and present him with an elegant Past Master's jewel."480

From 1790 until his election to Congress, nine years later,481 Marshall argued one hundred and thirteen cases decided by the Court of Appeals of Virginia. Notwithstanding his almost continuous political activity, he appeared, during this time, in practically every important cause heard and determined by the supreme tribunal of the State. Whenever there was more than one attorney for the client who retained Marshall, the latter almost invariably was reserved to make the closing argument. His absorbing mind took in everything said or suggested by counsel who preceded him; and his logic easily marshaled the strongest arguments to support his position and crushed or threw aside as unimportant those advanced against him.

Marshall preferred to close rather than open an argument. He wished to hear all that other counsel might have to say before he spoke himself; for, as has appeared, he was but slightly equipped with legal learning482 and he informed himself from the knowledge displayed by his adversaries. Even after he had become Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and throughout his long and epochal occupancy of that high place, Marshall showed this same peculiarity which was so prominent in his practice at the bar.

Every contemporary student of Marshall's method and equipment notes the meagerness of his learning in the law. "Everyone has heard of the gigantick abilities of John Marshall; as a most able and profound reasoner he deserves all the praise which has been lavished upon him," writes Francis Walker Gilmer, in his keen and brilliant contemporary analysis of Marshall. "His mind is not very richly stored with knowledge," he continues, "but it is so creative, so well organized by nature, or disciplined by early education, and constant habits of systematick thinking, that he embraces every subject with the clearness and facility of one prepared by previous study to comprehend and explain it."483

Gustavus Schmidt, who was a competent critic of legal attainments and whose study of Marshall as a lawyer was painstaking and thorough, bears witness to Marshall's scanty acquirements. "Mr. Marshall," says Schmidt, "can hardly be regarded as a learned lawyer… His acquaintance with the Roman jurisprudence as well as with the laws of foreign countries was not very extensive. He was what is called a common law lawyer in the best & noblest acceptation of that term."

Mr. Schmidt attempts to excuse Marshall's want of those legal weapons which knowledge of the books supply.